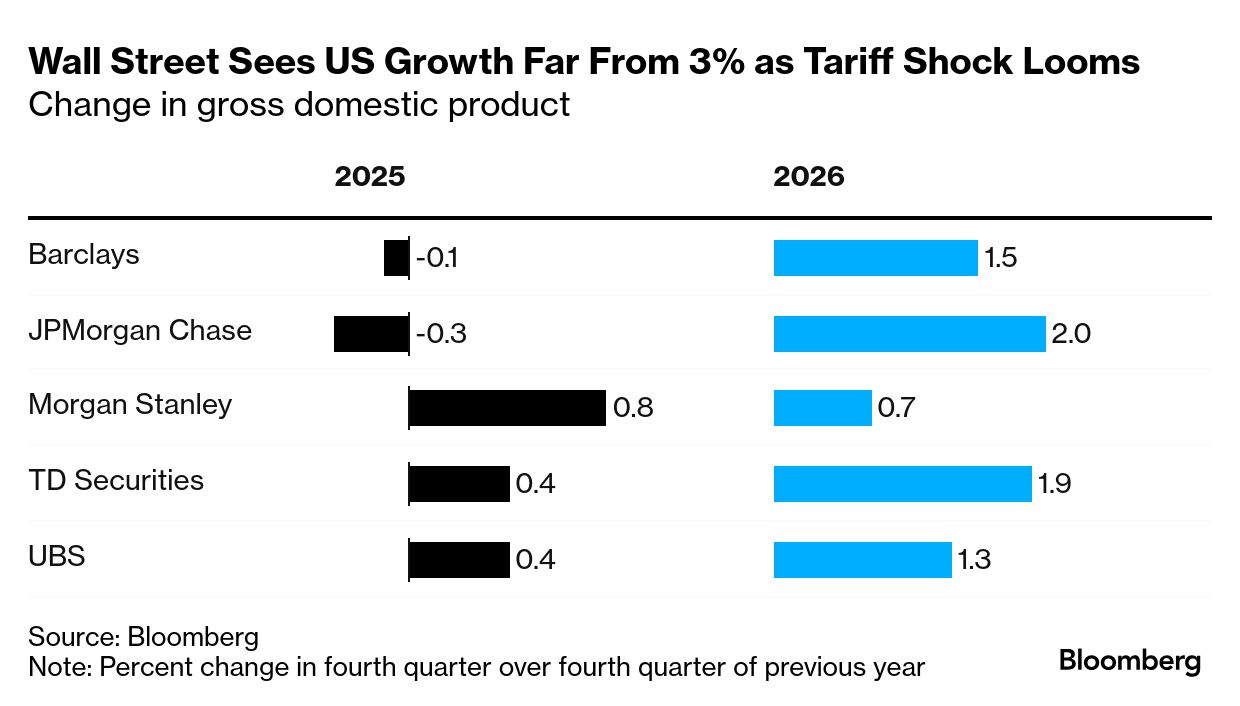

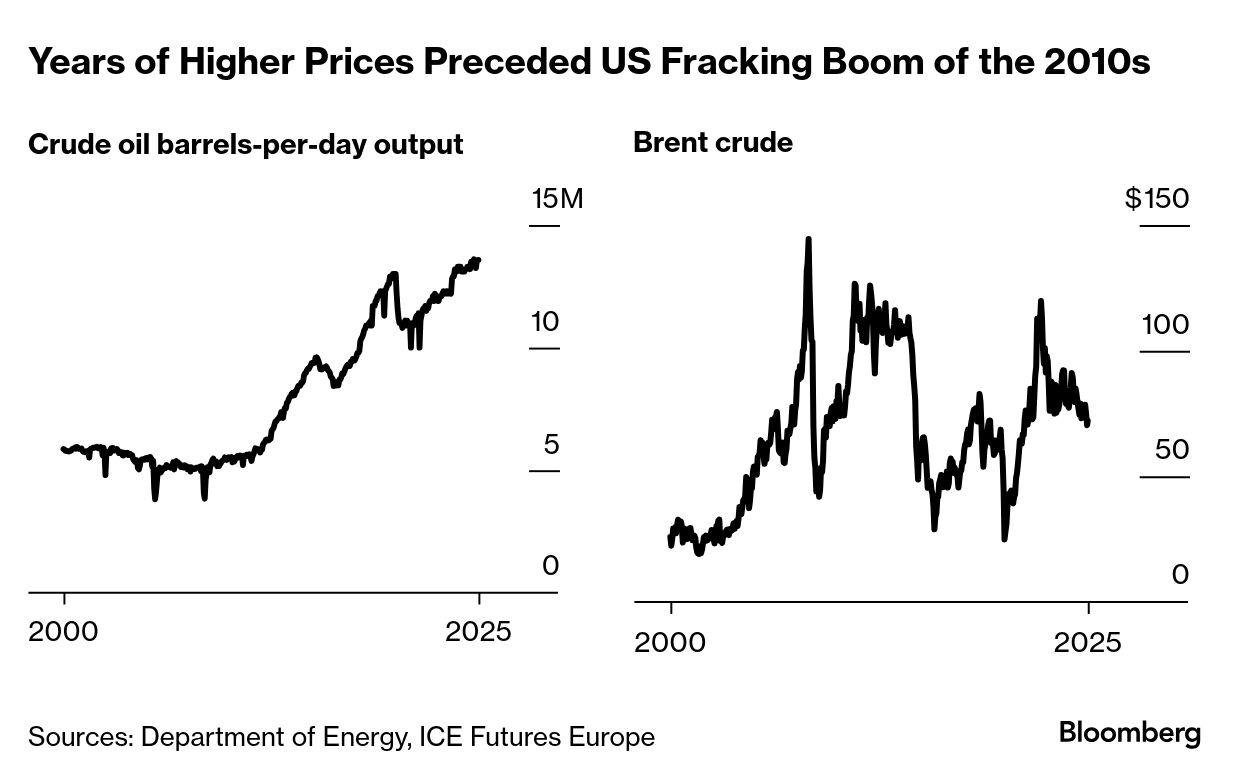

| I'm Chris Anstey, a senior editor in Boston, and today we're looking at some of the implications of the US tariff shock. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent took the helm of the US economy this year with a plan focused on three 3s: a 3% growth rate, a 3% budget deficit ratio and 3 million extra barrels of oil output a day. Trump's jacking up of American tariffs to the highest levels since before World War II have jeopardized possibly all three of those objectives. First off, growth: economists in recent days have rushed to slash their forecasts for this year to account for the hit to household purchasing power that's looming from the steep increase in duties on imported goods, which kicked in after midnight Wednesday. Unable to absorb all of the levies with their margins, companies will boost prices, eroding US consumers' real incomes. Not all the big Wall Street banks are calling for an outright recession, but none of them are projecting 3%. Which may not be an issue for Bessent and his colleagues — after all, he warned that there would be a "detox period" for the economy as it transitioned away from what he described as a Biden administration's template of government-backed growth. The blow from tariffs also appears, in may forecasts, not to be (yes, that word again), transitory. Or at least not very transitory. Economists are also shaving 2026 projections, mainly below 2% let alone 3%. As for the budget-deficit 3%, tariffs will generate revenue. An analysis by Rana Sajedi and Maeva Cousin of Bloomberg Economics suggests that all of the levies imposed to date would throw off around $300 billion in annual revenue on average. That's at the low end of a range Bessent has floated of up to $600 billion. But weaker economic growth means lower receipts to the Treasury from income and corporate taxes than would otherwise have been the case. The slide in the stock market, if sustained, also bodes ill for capital-gains revenue. If interest rates are lower thanks to weak growth, that would save the government on debt-servicing costs. But net-net, it's tough to see how Washington gets closer to 3% of GDP from the excess of 6% ratio of recent years. And if the US tips into a recession, those in the past have driven up Treasury borrowing needs, not shrunk them. Finally there's oil, output of which climbed by more than 2 million barrels a day to record levels during the Biden administration. A challenge to adding another 3 million a day is that crude prices lately have been sinking — thanks in large part to the deteriorating outlook for economic growth, caused by tariff fears. Even as fracking technology improved over the decades, it took a sustained increase in prices over a years-long span to convince producers to ramp up investment in American capacity back in the early 2010s. When prices slid in 2014, it upended the calculations of many businesses and sent default rates soaring, in a sobering lesson for the industry that's unlikely to have been forgotten. So it's not clear, even with deregulation, that the business case is so strong for the energy industry to ramp up production from already-elevated levels. Bessent's formula never had a target for the goods trade deficit, which has averaged roughly 4% of GDP the past five years. Arguably a shame, as that's one metric that would seem ripe to get to 3% before very long if the tariffs stick. The Best of Bloomberg Economics | - Ray Dalio warns that investors are too focused on tariffs and not paying enough attention to the breakdown in major monetary, political, and geopolitical orders.

- South Korea is seeking a "big" trade deal with the US after a phone call between Trump and Acting President Han Duck-soo.

- India cut rates and signaled more easing, New Zealand reduced borrowing costs, Kenya did by more than expected, and Uruguay hiked.

- Argentina reached an accord with International Monetary Fund staff, a major step before the lender officially votes on a new $20 billion deal.

- Spain is pushing for an EU pivot to China to counter Trump, while the Bank of France chief says the euro zone needs a rate cut "soon."

- Americans have plenty of housing wealth, but millions of homeowners are effectively locked out of accessing it, a study found.

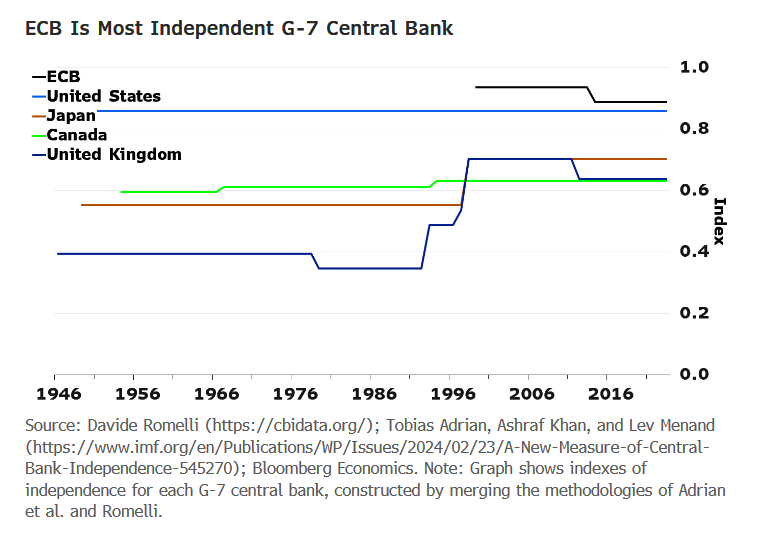

A new measure of central-bank independence compiled by Bloomberg Economics, incorporating information going back to 1951, suggests that the US Federal Reserve is facing the biggest challenge to its autonomy over that space of time. The European Central Bank scores the highest in the new metric, which so far focuses on the G-7. The index is based on provisions coded in law, and measures independence along seven dimensions — two of which rest on job security. Where policymakers cannot be removed for mere policy disagreements with political leaders, central banks score higher. Trump this year has fired several federal agency leaders assumed to have had a measure of job security, David Wilcox — director of US economic research for Bloomberg Economics — wrote in a note. If the Supreme Court upholds the actions and overturns past precedent, the president potentially could get power to fire Fed board members. The Fed's index score would then drop, and "the real-world consequences could be big," Wilcox wrote. - View the full note on the Bloomberg terminal here.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment