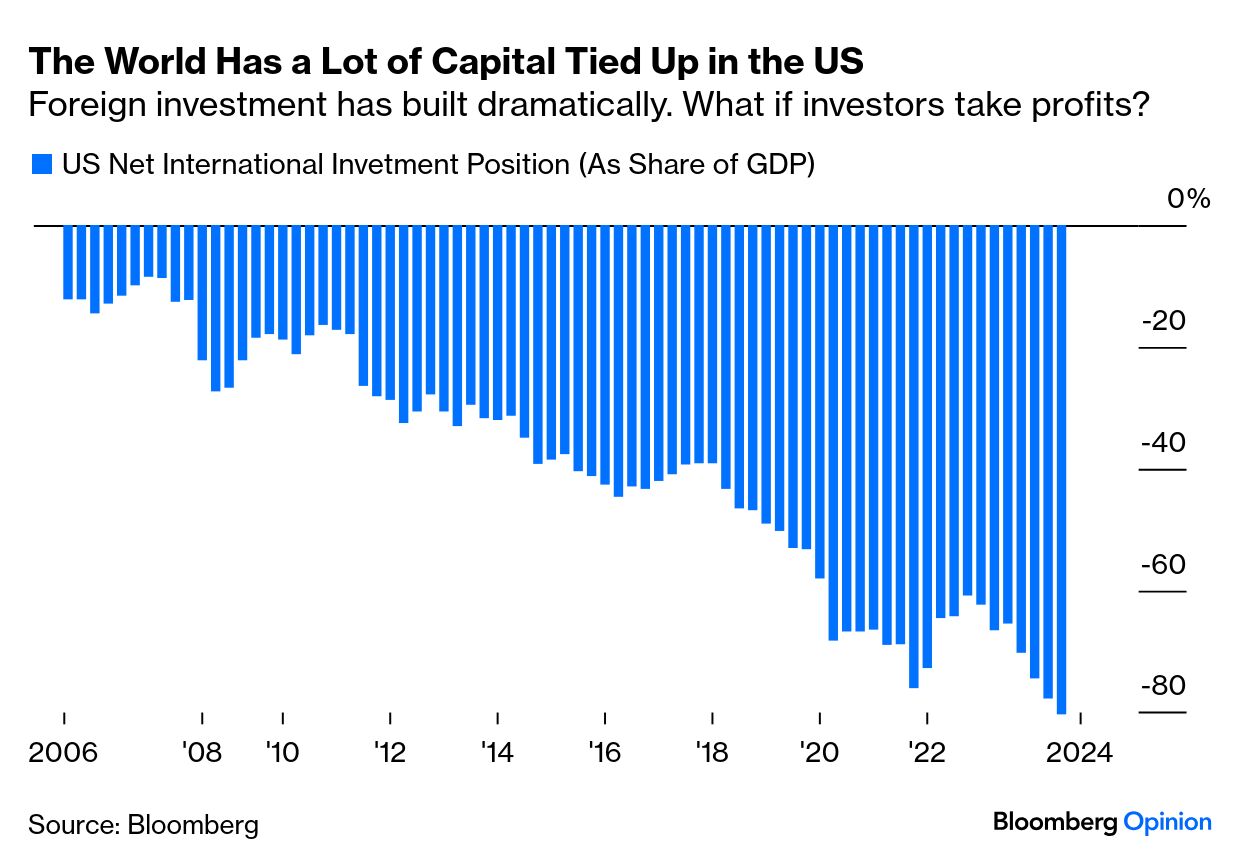

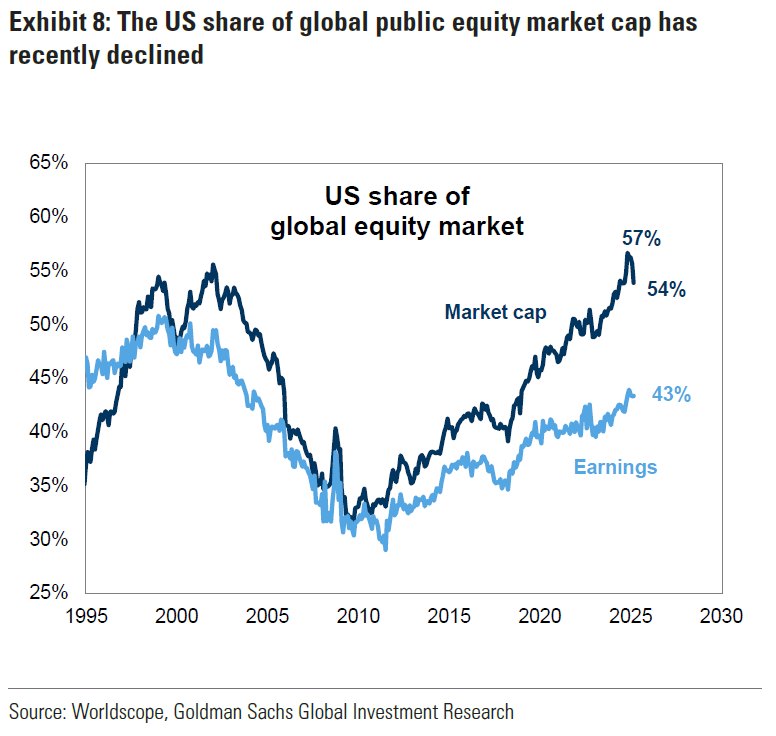

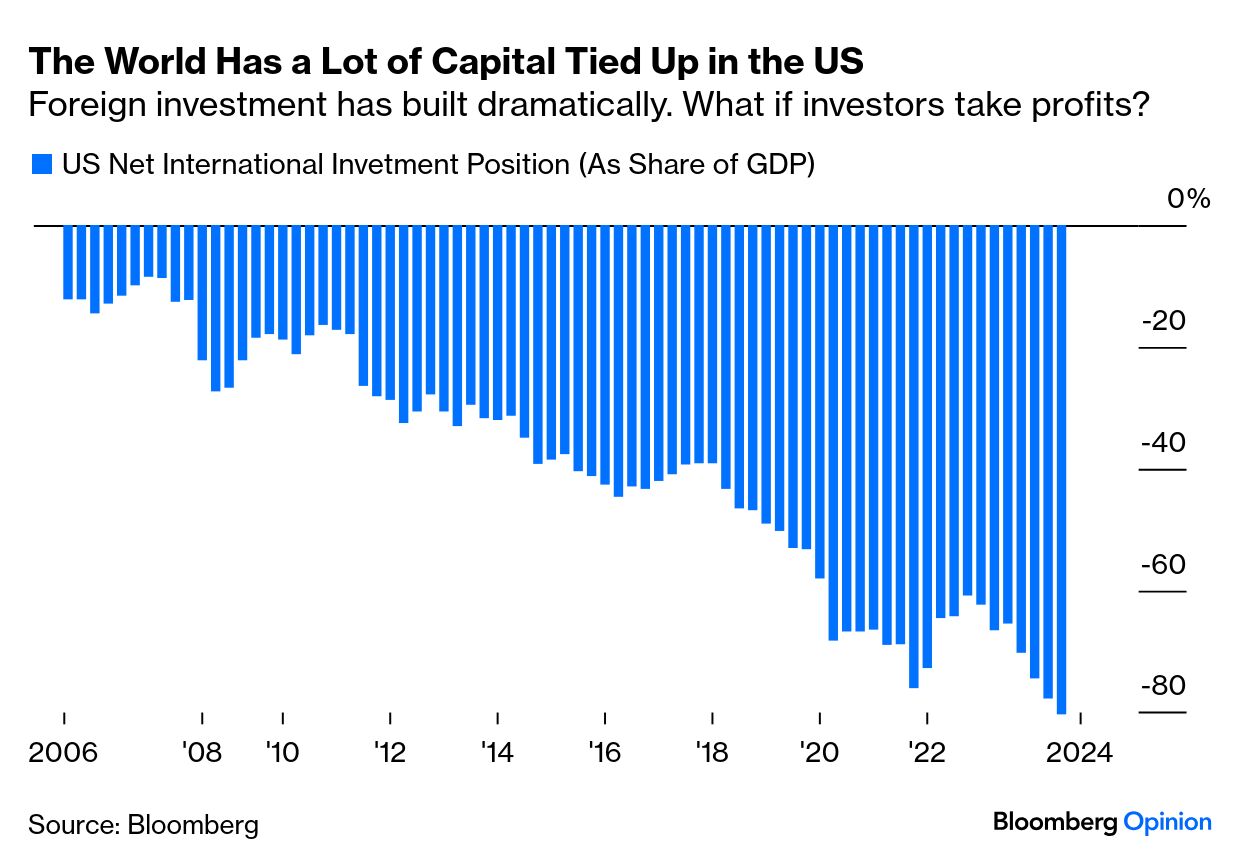

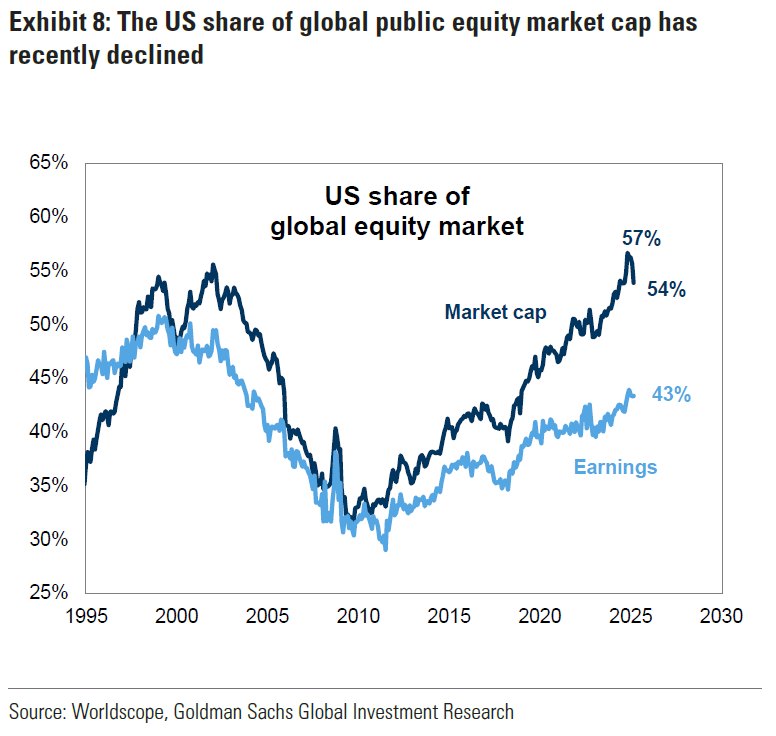

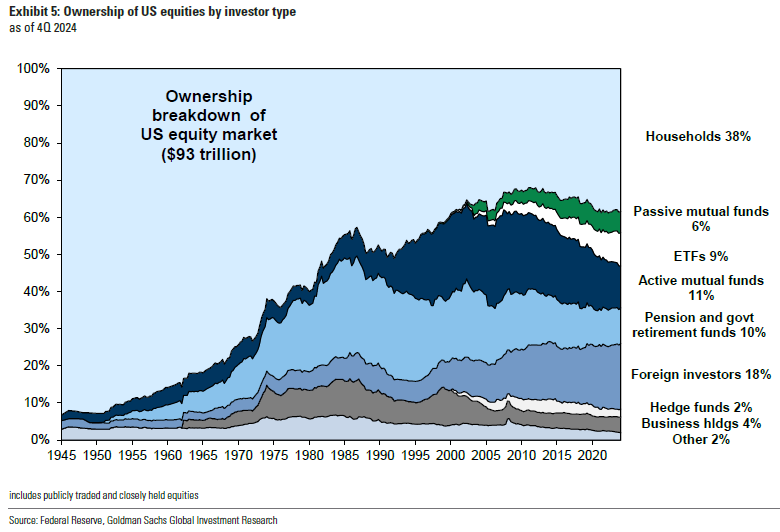

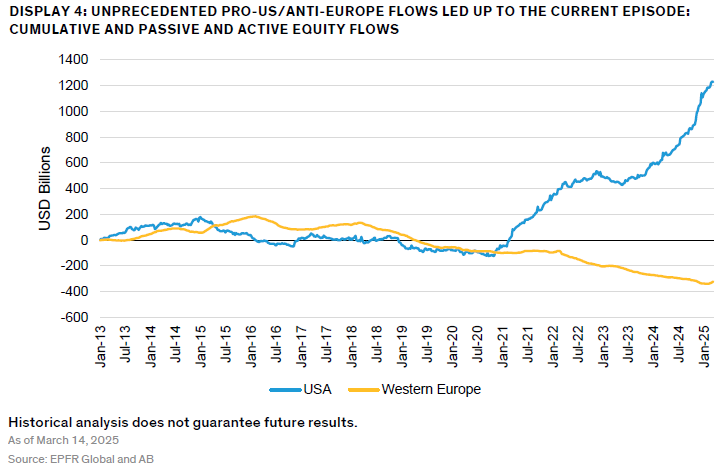

To get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here. | Global Imbalances II: This Time It's Personal | About 20 years ago, there was one fear above all that kept investors and regulators awake at night: global imbalances. In particular, there was fear over the huge growth in Chinese holdings of US Treasuries as the world's new exporting powerhouse looked for a place to stash its profits. Why was this a problem? First, there was a belief that it kept long-term interest rates low, and hence contributed to the lax credit conditions that eventually sparked the Global Financial Crisis. The Federal Reserve hiked short-term rates, but 10-year yields held below the 5% level — and all hell broke out when they finally surged through that landmark in the summer of 2007. Second, there was a fear that all those holdings gave China a hold over the US. They represented liabilities that Uncle Sam owed to Beijing. How could this go well? And what if China decided to declare economic war and dump its Treasuries in a hurry? Acting like a Bond villain, China's leader could threaten to tank the US economy in one fell swoop. After a while, people worked out that China had a lot at stake in the value of its Treasury holdings, and that any such threat would also inflict terrible damage on its own economy. Global imbalances remained, peaking after the GFC. A very gradual decline in Chinese holdings has in the last three years accelerated, in a way that does overlap with the beginning of a secular bear market for Treasuries. But now, this is perceived as an act of self-defense as China battles its own problems, and not as anything aggressive: The reason to bring this up now, as the world braces for a concerted attempt to deal with imbalances in trade flows, is as a reminder that it hasn't been long since the greatest worry was over imbalanced capital flows. And ironically, capital imbalances have accelerated since the GFC, to a far, far greater extent than trade flows. America's net international investment position, in which foreign holdings of US assets are subtracted from US international stakes, has collapsed in the years since the crisis. Incredibly, the deficit is now equivalent to more than 80% of gross domestic product. Nobody is worrying about some Bond-villainesque move to sell all of those holdings at once, because it isn't going to happen. But the scope for damage to US assets if that money begins to retreat is obvious:  Those who hold US assets are beginning to look worryingly overexposed. David Kostin, chief US equity strategist of Goldman Sachs, shows that the US share of the global equity market reached an all-time high before the recent turnaround, overtaking the previous record from the dot-com era. Of course, much of this is because of superior performance by US companies. But not all of it. The US share of global earnings remains well below its highs from 25 years ago. That's even after accounting for the phenomenal global success of US Big Tech:  Foreign owners have a far greater role in the US equity market than they once did. This chart from Kostin shows how ownership of US equities has moved since 1945. Once dominated by wealthy American households, the market first institutionalized as mutual funds, pensions and then exchange-traded funds took dominant positions. Since the GFC, the story has been of the returning influence of individual owners (both a symptom and a cause of growing inequality), and ever greater foreign influence: Flows have become particularly extreme since the pandemic. This is in part because of the excitement around the Magnificent Seven and also reflects the collapse of confidence in Europe. Flows out of Europe and into the US, detailed here by Alliance Bernstein's Inigo Fraser-Jenkins using EPFR data, have been spectacular in the last year: The upturn in flows to Europe is just faintly visible at the end of the chart if you squint. The continent accounts for 49% of foreign ownership in the US, so these flows matter. Now, the question is whether the money could leave as quickly as it came. The reasons so much money arrived in the first place are profound. Fraser-Jenkins summarizes them as follows: 1. A highly favorable demographic outlook versus other developed economies and China; the growth in the US working-age population is set to decline but remain positive, whereas in those other regions it is in outright contraction.

2. A structurally higher level of profitability for US companies and a successful tech sector that imply an ongoing ability to earn higher margins.

3. Stronger geographic security of supply chains than other regions.

4. Benefits from the scale of its home market.

5. The dollar's reserve-currency status; despite attempts to undermine this, it is set to remain in place for the foreseeable future.

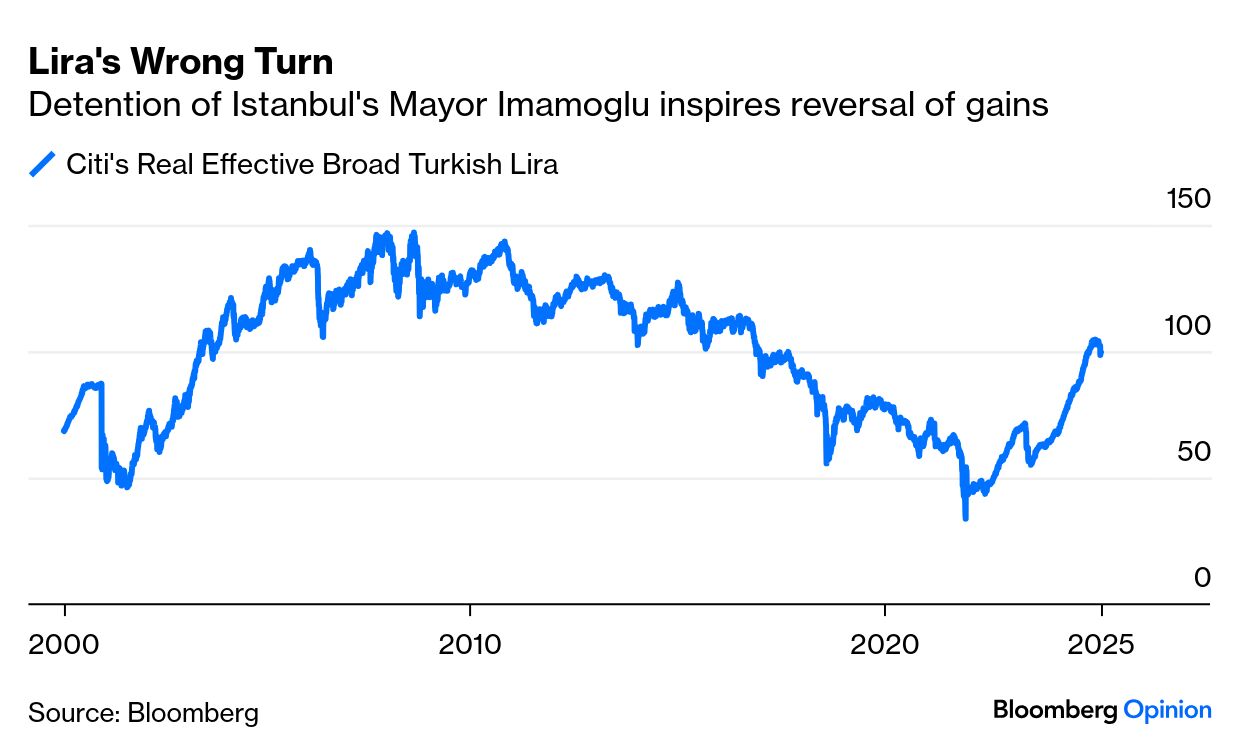

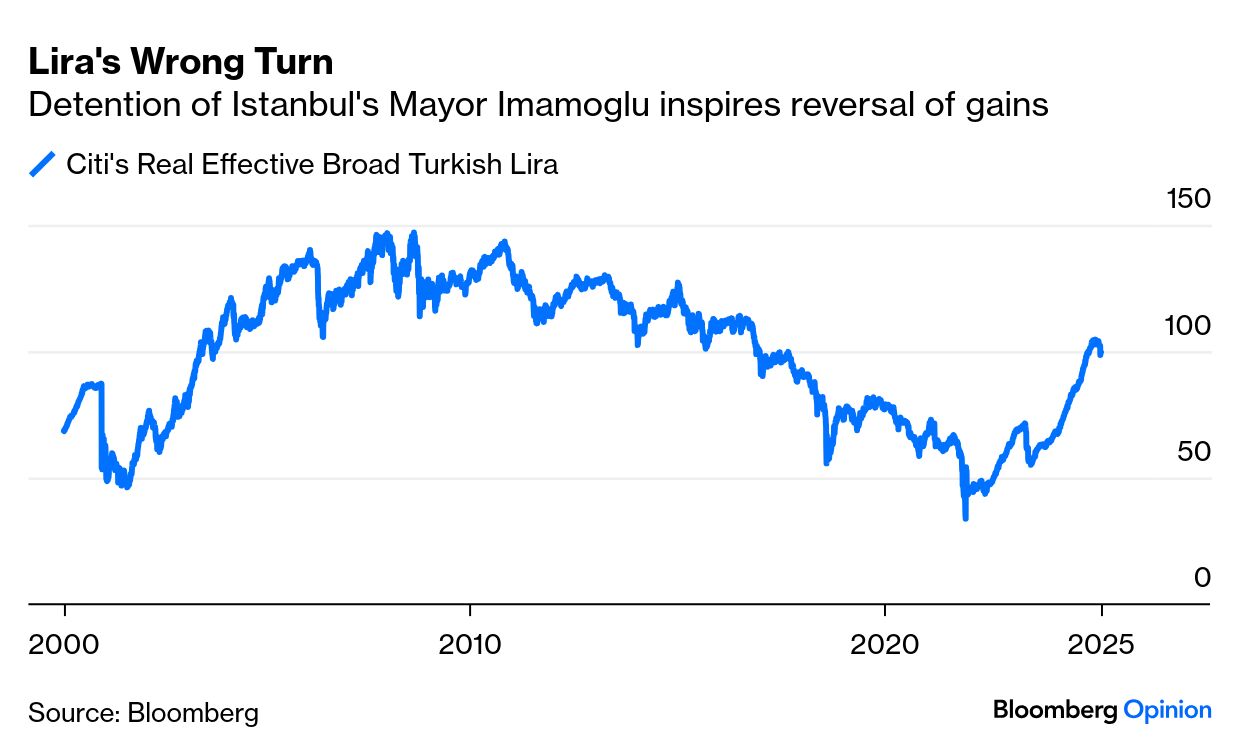

None of these can go away quickly. It's therefore hard to see the money flowing out as fast as it arrived. The risks are softer and more intangible. Current American behavior appears designed to lose friends. As Points of Return has been saying, the critical question is whether the world has lost its trust in the US. If it has — and the way Canadians are boycotting US goods in combination with the dismay in Europe strongly suggest as much — then the nightmare scenario that people batted around 20 years ago with respect to China begins to get believable. Beyond that, the emerging narrative involves a world with several spheres of influence that try to be self-reliant. That will involve capital flowing home. And as we've seen, that's potentially mega-bearish for the US. There's also the problem that capital can move very, very easily. With ETFs, you can switch millions out of the US with the press of a button. Changing pension regulations can require funds to bring money home at the drop of a hat. This isn't notional. Sixteen years ago, when still in the worst of the GFC, I wrote for my old employers about a ruse Mexican pension regulators used to abort a run on the peso. All public pension managers were abruptly told to end international diversification and bring money home to Mexico. The result was a rally for the currency and a big surge for the stock market. As countries arm themselves with sovereign wealth funds, capital protectionism like this gets easier and easier to do.  Canadian travel to the US is plummeting. Photographer: James MacDonald/Bloomberg Six years ago, I argued for Bloomberg Opinion that capital wars were easier to win than trade wars, after a campaign led by Marco Rubio, now secretary of state, to make federal pension funds divest from China. In an era of indexes and ETFs, it's easy to do. And it doesn't need much direction. If pension trustees believe they will get a quieter life if they avoid investing in fossil fuels, or Israel, or woke companies or whatever, then that's what they'll do, very easily. Judging by Canadians' changing travel plans, investment groups there might find a similar temptation to make life easier by keeping out of the US. None of this can happen overnight. But it can happen a lot quicker than trade flows can adjust, and America has the most to lose. Even if it doesn't have to contend with Ernst Stavro Blofeld.  | | | Political instability always has a way of spooking investors. Often, the consequences of these missteps are far-reaching, hitting domestic economies even harder. It's Turkey's turn to revisit these lessons. As a country with a storied history of authoritarianism, the odds were always that markets would revolt against Recep Tayyip Erdoğan after the arrest of his rival, Istanbul Maayor Ekrem Imamoglu. It didn't matter whether the corruption charges were valid. The chances that this would be seen as politically motivated were extremely high, as attested by the waves of protests in the past week across nearly two-thirds of Turkey's 81 provinces. Reports of clashes with law enforcement are rife. Investors did what they mostly do in these situations: flee. This is how the Turkish lira reacted to the chaos:  On the face of it, despite a course reversal, the lira appears to have weathered the onslaught. However, there's more to it. Keeping the currency steady came at a considerable cost to the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, or CBRT. Bloomberg Intelligence's Selva Bahar Baziki estimates that between March 19 and 21, the bank spent almost $27 billion of its forex reserves to prop up the lira: If these operations are maintained at the pace as seen this past week, then we forecast net reserves dropping to zero by mid-April — that's faster than our initial expectation of that happening in two-to-three months. The faster bleeding of reserves could see domestic lira sentiment swiftly turn sour, resulting in residents switching to dollars at an accelerated pace and compounding pressure on the lira.

Fears that the worst is yet to come are reasonable. However, Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek assured investors Tuesday that whatever it takes would be done to stabilize markets, blaming increased forex demand on foreigners, which he says has subsided. The assurance became necessary after last Thursday's unexpected overnight lending rate hike by 200 basis points to 46%. With the central bank's hard work to rein in stubborn post-pandemic inflation threatened, Governor Fatih Karahan needed to do something. April's data print should reveal whether last week's lira selloff fed into inflation. Karahan said the bank would act accordingly at its next meeting, where a pause was originally the base case. Now, a hike cannot be ruled out, though Societe Generale's analysts including Phoenix Kalen argue it's not likely: Instead, we expect the CBRT to tighten liquidity conditions and use the higher ceiling of the interest rate corridor... In the spring months, the start of the high tourist season and the associated hard currency inflows should also help stabilize the lira, and total returns are likely to be elevated again. We now expect the CBRT to cut by 150bp in June and again by 200bp in July and to end the year at 35%.

Istanbul erupts. Photographer: Kerem Uzel/Bloomberg The path to normalcy comes paved with strong caveats. Much as external politics matter, such as relations with the US, resolving domestic disturbances is paramount. Inflows from tourists could be scuttled if the unrest persists. Newly ignited inflation would likely remain sticky, with Kalen projecting consumer prices rising 30.4% for the year, well above the CBRT's latest forecast of 24%. Still, GivTrade's Hassan Fawaz notes that such a reversal in the lira's fortunes poses a significant risk to economic stability at a time when international investors are cautious about emerging markets. Another possible fallout is that the chaos exacerbates capital outflows, making it harder for Turkish businesses to access financing. Meanwhile, the protest-driven stock market rout appears to have bottomed out after the capital regulator banned short-selling over the weekend and relaxed share buyback rules to prevent further equity losses. The ban isn't entirely new, broadening previous restrictions affecting only the top 50 listed companies. Like any ban on short-selling, the relief it provides will only be temporary at best. The buyback move allows listed companies to repurchase shares at prices above the last market close. The minimum equity capital protection requirement for margin trading was also reduced to 20% from 35%. All of that engineered a respectable bounce: For now, policymakers' overtime work is stopping the bleeding. Erdoğan's relief over the temporary halt to the market rout could be short-lived if the events that prompted it — which he himself prompted — degenerate into deeper disorder. — Richard Abbey Mikey Madison, freshly garlanded as best actress at the Oscars for her performance in Anora, turns 25 today. I've just caught up with the movie, so this is a good time to recommend seeing it. It's very funny, close to the bone (there are a lot of scenes in strip clubs and the whole movie comments very blackly on sexual exploitation), and ultimately very moving. Madison is something extraordinary. She's a sex worker, she gets the useless and spendthrift son of a Russian oligarch to pay her massive amounts of money, and by the end it's clear that she's been treated terribly. This is one of the best scenes. Yes, worth seeing. It might even have been the best movie of last year. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Marc Champion: US Allies Get a Signal Chat's Worth of Red Flags

- Juan Pablo Spinetto: Mexico Should Roll Out the Asphalt Carpet for BYD

- Lionel Laurent: Paris and London's Wealth Loss Is Dubai's Gain

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

No comments:

Post a Comment