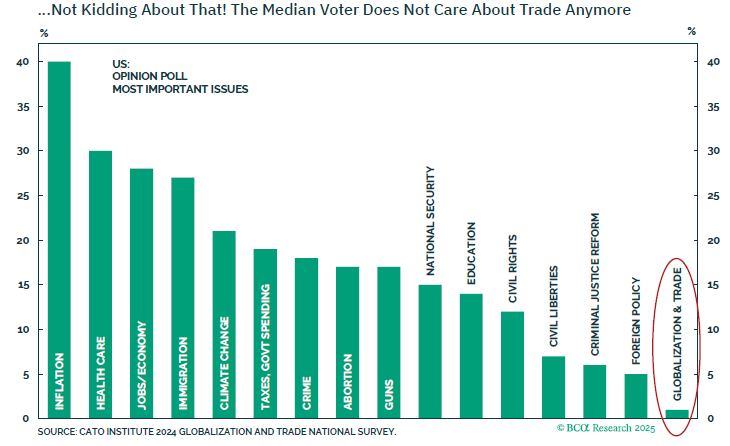

| It can be difficult to remember that the Mar-a-Lago Accord hasn't happened yet. Leaders haven't been convened to Palm Beach, and there's no agenda for what such an accord could include. But that hasn't stopped people talking or journalists writing about it. This shows the total number of stories (from all sources) mentioning a "Mar-a-Lago Accord" each day on the Bloomberg terminal for the last year: But what is it, and can it really happen? There are huge variations, but the common themes seem to be that an accord would be an international agreement designed to: - Weaken the dollar, and

- Prompt far more foreign direct investment into the US.

The overarching aim is to bring back manufacturing jobs at a price that the US can afford or, alternatively, to roll back globalization so that the US can escape its greatest downsides (inequality and the hollowing out of the working class) without sacrificing its upsides (low inflation, strong asset prices and low interest rates). Tariffs should be viewed primarily as a toll to get there, and also as a fallback option if an accord can't be reached. These are wholly reasonable aims, for which the administration has a mandate. It's not clear that they're achievable, or that other countries have any reason to go along with them. Adam Tooze of Columbia University describes the idea as "on its face a far-fetched policy proposal" in which it's easy to pick holes. He suggests that the notion is only taken seriously because "we are all struggling to find some kind of rational purchase on the unhinged situation created by the Trump administration." These are strong words, but the retreat of stocks in the last few weeks is in large part driven by investors coming around to his point of view. So how does the US propose to make this happen? Various possibilities include: - Threats of tariffs.

- A sovereign wealth fund to manipulate the currency and replace flows of capital from abroad.

- Coercion on defense; those who agree can benefit from the US security umbrella while those who don't cannot, or as Stephen Miran, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, put it: "Countries that want to be inside the defense umbrella must also be inside the fair trade umbrella."

- Big cuts to the federal budget to reduce the deficit.

- Putting pressure on the Federal Reserve (under new leadership next year) to cut rates. (The president opined on Truth Social that "The Fed would be MUCH better off CUTTING RATES as US Tariffs start to transition (ease!) their way into the economy.")

- And possibly Tobin transaction taxes, to create a cost for holding US dollars as reserves.

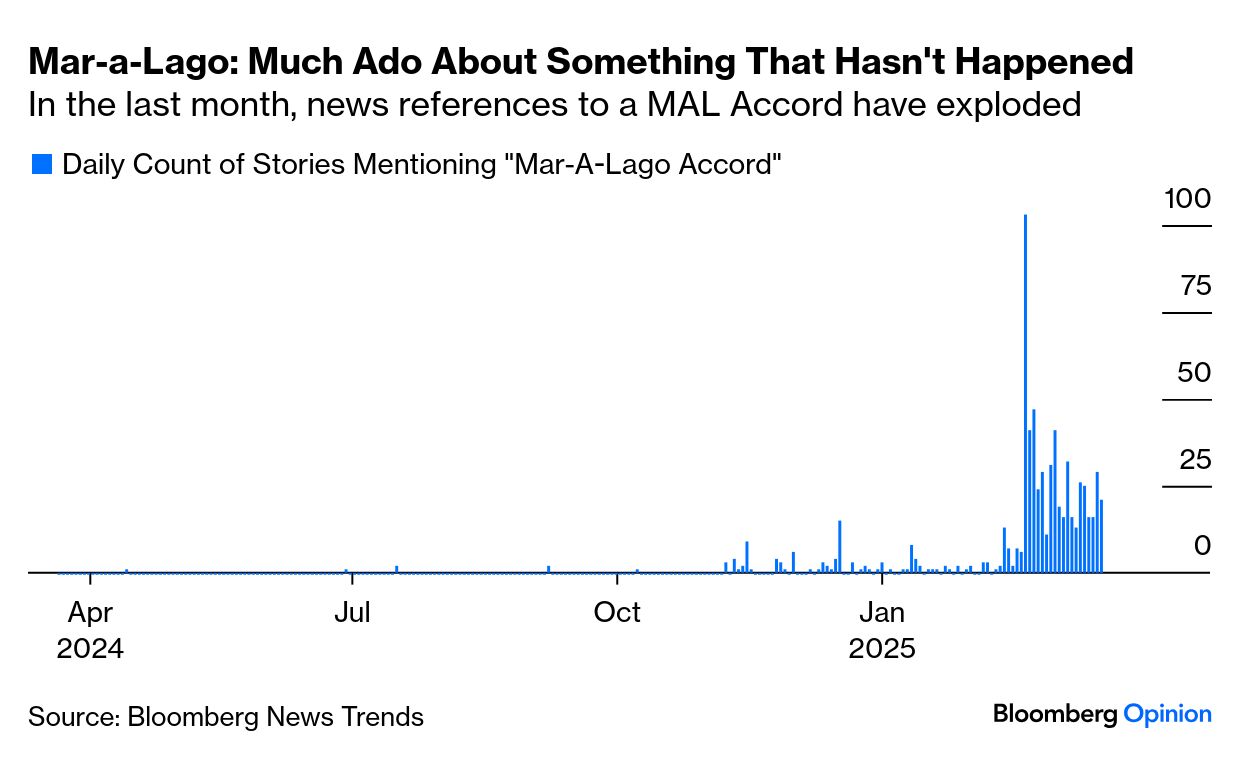

We've seen action on the first four already, although with minimal detail on all of them. The fifth, as foreshadowed by the presidential overnight communication, would be most unwelcome on markets. Beyond that, implementation of any of this promises to be a huge challenge. That's because, first, the US dollar isn't as massively overvalued as it was at the time of the 1985 Plaza Accord (struck at a New York hotel that subsequently belonged to Trump for a while), which is the model for an international agreement to weaken the dollar. That makes it harder to bring down in a significant way. On a real trade-weighted basis, the currency is certainly very expensive, but not as extreme as 40 years ago, according to the Fed's own index: Further, Plaza involved only the biggest countries in the then-developed capitalist world. The globe has since gotten bigger, making it far harder to find a deal that everyone can live with. While Plaza worked for the US, it wasn't so great for Japan, which entered a long-lasting slump a few years later. That won't be lost on those who would stand to lose from a weaker dollar, such as China. Tiffany Wilding, economist at Pimco, also points to the growth of foreign exchange markets since Plaza: The sheer scale of the interventions required to create a meaningful dollar devaluation is staggering. Currency markets today see daily average turnover of some $7.5 trillion, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Even after adjusting for inflation, that's about five times greater than the volume in 1989, in the years after the Plaza Accord.

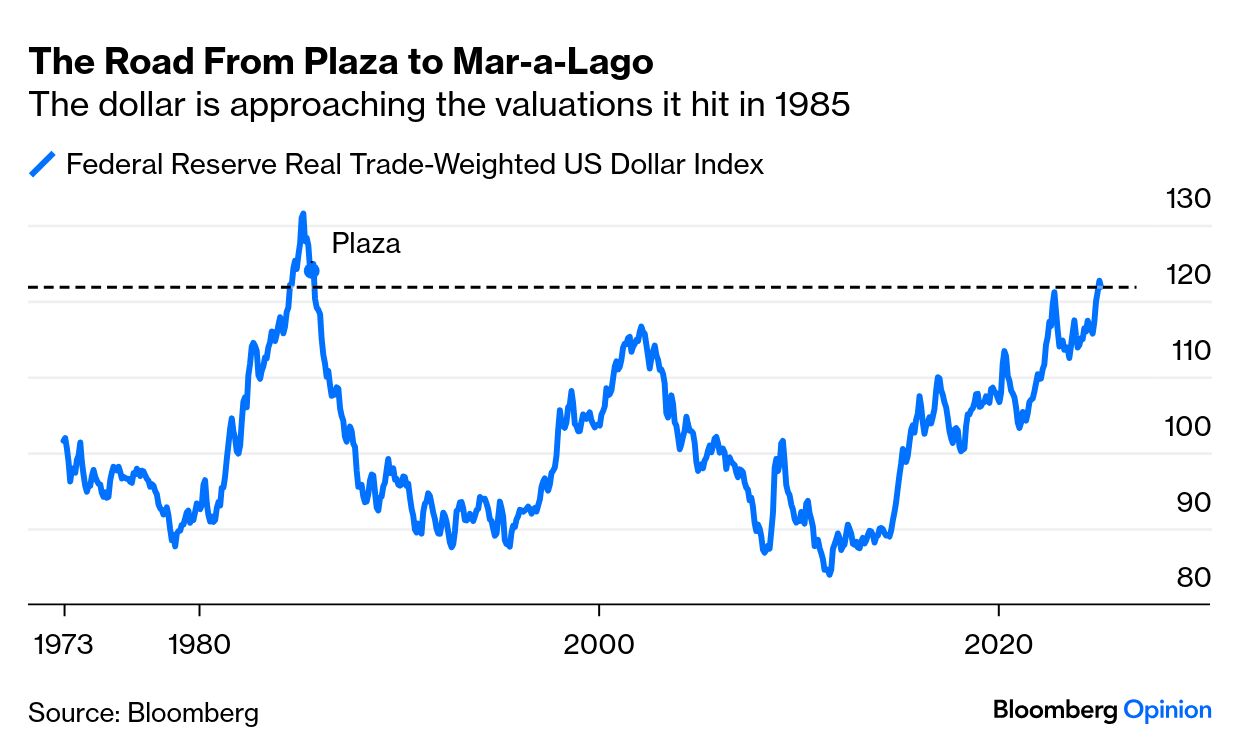

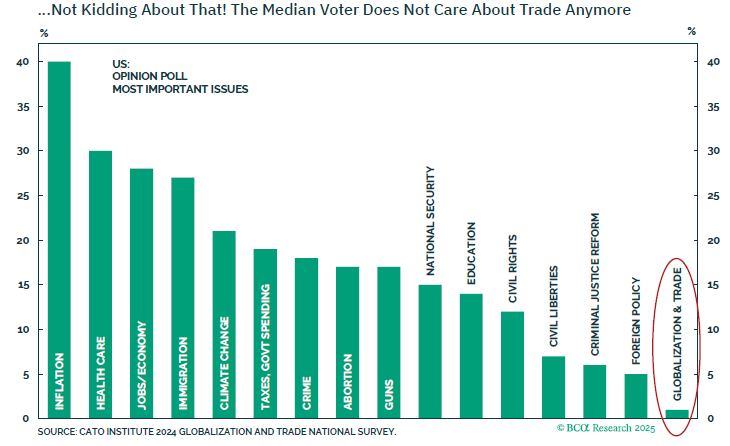

Any agreement at Mar-a-Lago will not be able to weaken the dollar anything like as much as Plaza did by intervention alone. Another problem is inflation. Globalization over time minimized it; and public tolerance for rising prices, we've learned in the last four years, is non-existent. Further, the concern is less inflation — slowing the rate at which prices are rising — as much as the price level. There's a case that tariffs don't create inflation, and the debate has already entangled the Fed's Jerome Powell. It's impossible to deny that they create a one-off rise in the price level. Using tariffs to create leverage, or as a source of revenue, is not the simple call it appears. It might hurt US counterparties more, but it will create much political pain at home. Marko Papic of BCA Research points to a range of polls showing that voters care deeply about prices, while trade doesn't matter to them. The political difficulty created by a spike in prices after Trump levied tariffs would be hard for the administration to navigate:  The greatest problem for any deal is getting others to agree. This is where the US may have already overplayed its hand. One widely circulating version of a MAL Accord had Europe agreeing to rearm by buying US weapons, in return for avoiding tariffs. But Trump 2.0 has shown itself so willing to withdraw from the Atlantic alliance that now even Germany's once-staunchly Atlanticist new chancellor says the country needs "independence" from the US. European, not American, arms manufacturers are benefiting. The first act of Canada's new prime minister has been to discuss defense with European leaders. Rather than accede to US demands, the international response so far has been to look for alternatives. This is understandable, as it grows ever more politically unpalatable for foreign leaders to rely on the US — and a range of countries now appear to be planning their own nuclear deterrents, which makes the security umbrella less important still. Finally, Trump's very unpredictability increases his leverage, but also tends to deter people from feeling confident in reaching an agreement with him. Former mentor and colleague Martin Wolf put it this way in the Financial Times: He has, after all, abandoned Ukraine, put the commitment to NATO into doubt and mounted an assault on Canada. Is this administration capable of making a deal any sane person or country should trust? I think not.

The upshot is that while the US plainly would prefer some help weakening the dollar, the chances are that it will actually impose the tariffs. Trump refers to April 2, when his plan for reciprocal tariffs will be unveiled, as "Liberation Day." Peter Tchir of Academy Securities argued that global tariffs will mean a "rocky road ahead for the economy": There is a lot of "chatter" about uncertainty. My fear is that the market isn't pricing in what seems more and more certain — global tariffs shocking global supply chains.

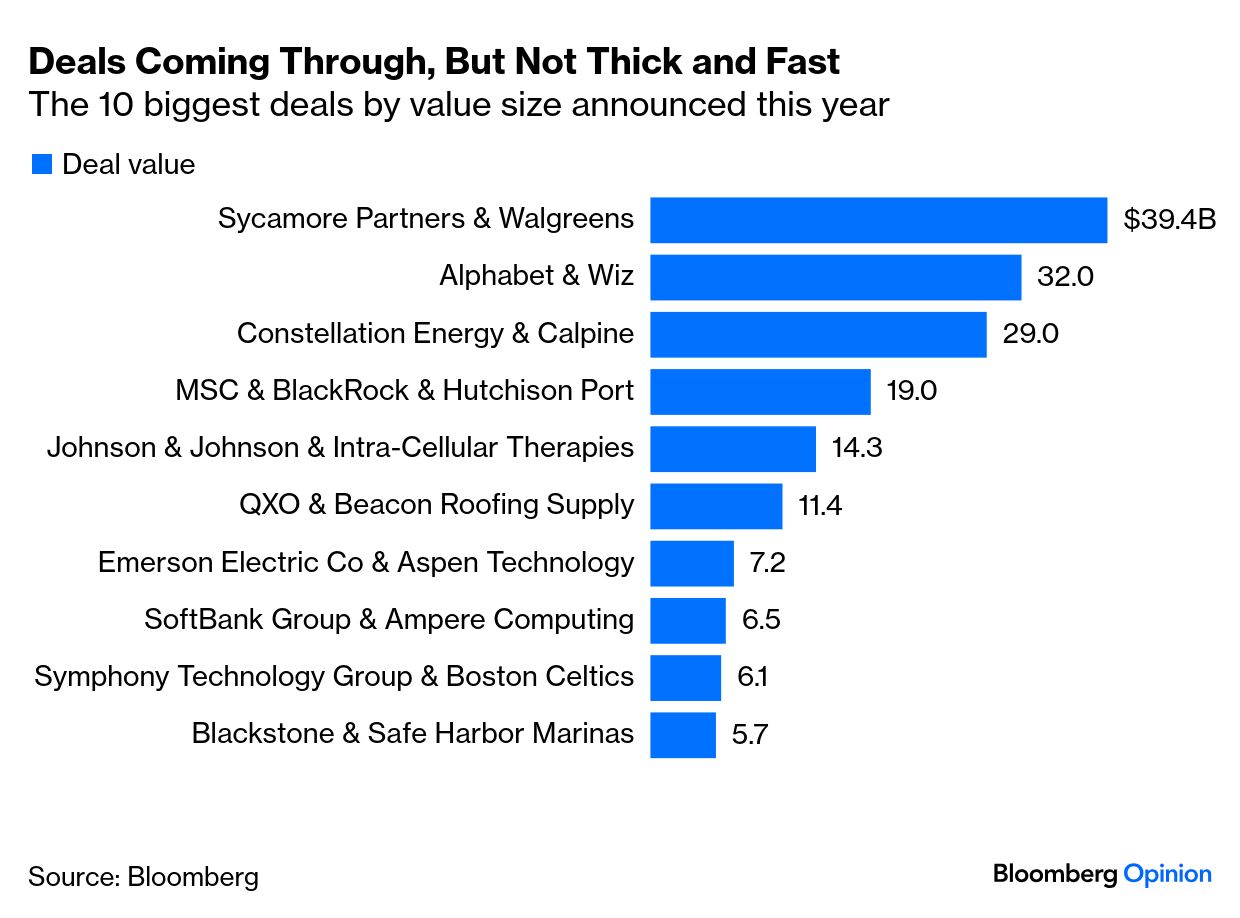

Quite. Plenty of people on Wall Street are attracted to the various versions of the Mar-a-Lago Accord that have been circulated. Very few share the president's enthusiasm for tariffs. It's best to brace for them to happen. Google's $32 billion deal to buy the Israeli startup Wiz Inc. this week was an instant head-turner. It's among the biggest deals so far under a new administration expected to turbocharge dealmaking. It was also about time, as the expected surge hasn't materialized. Two months into Trump's second term, the value of announced mergers and acquisitions involving US companies stands at about $387 billion. That's basically flat, down roughly 2% compared to this point in 2024: A recent survey of dealmakers by Gladstone Place Partners found that 63% saw the Trump administration as the macro factor that would have the biggest impact on M&A in 2025 — but his aggressive tariff approach has generated enough uncertainty to counteract this. Tariff confusion also makes it harder for the Fed to cut rates, crucial to the borrowing and debt-servicing costs for the private equity firms at the heart of these deals. But while the growing doubts make sense, SLB Capital Advisors' Scott Merkle says that private equity firms and investment bankers are talking about upcoming activity: Deals in the pipeline that are viable at prevailing rates should move to closing, and the possibility of lower rates ahead may provide another push for M&A activity down the road.

While Trump can't cut rates, his influence on easing regulatory constraints is unmatched. But progress has been painfully slow. Meaningful deregulation would make a big difference. A&O Shearman found that despite last year's M&A recovery, more deals were frustrated by antitrust authorities than in any of the previous four years, with a striking 50% rise in transactions abandoned due to antitrust concerns. Trump's unbridled executive power should make it easy for him to restore confidence. So far, the Federal Trade Commission isn't loosening up as hoped. Bloomberg News reported earlier this month that the body is continuing its probe on Microsoft Corp. It's unclear how this ends, but the optics surrounding the Justice Department's desire to proceed with a Biden-era goal to break up Google's business is not encouraging. This shouldn't be that surprising. A&O Shearman's report suggests that as much as regulatory easing is expected, a strict approach to M&A in sectors such as technology will remain. The broader macro backdrop also matters. Rising recession fears and stock market downturns are troubling signs for dealmaking. BofA's head of US small and mid-cap strategy, Jill Carey Hall, points out that good years for M&A also tend to follow good years for market returns — like 2024. However: Deal activity tends to be higher when growth expectations for small caps are higher. And while growth expectations have improved, they're still below average, so not as many great growth prospects in small caps relative to history. M&A is also correlated with economic growth, and economists expect growth to remain healthy but to moderate in 2025.

With some clear-cut action on deregulation, this might still be a big year of deals. Resolving the tariffs uncertainty would also help. Untile then, dealmaking won't deliver for smaller companies as had been hoped. —Richard Abbey Is it good when your sports team sells itself for the highest price a franchise has ever fetched? That's just happened to the Boston Celtics, reigning champs of the National Basketball Association, who have been acquired by a group led by one of their childhood fans for $6.1 billion. That beats the previous record of $6.05 billion paid for football's recently renamed Washington Commanders, and is 50% above the previous record for a basketball team. No franchise in any league has ever sold for a higher price, although according to Forbes — which last year very accurately valued the Celtics at $6 billion — there are 18 teams worth more. Does this matter? There's something reassuring about a club falling into the clutches of a fan, as it implies that the ownership won't be a purely economic endeavor; they want trophies, and won't waste energy on things like closing the staff canteen. With luck, more moments like this or this will be a priority. Have a great weekend everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment