| Amid all the Trump 2.0 excitement, his Treasury secretary, the highly respected hedge-fund manager Scott Bessent, has enunciated a clear economic target that he shares with the president. "He and I are focused on the 10-year Treasury," he said in an interview with Fox Business. "He is not calling for the Fed to lower rates."

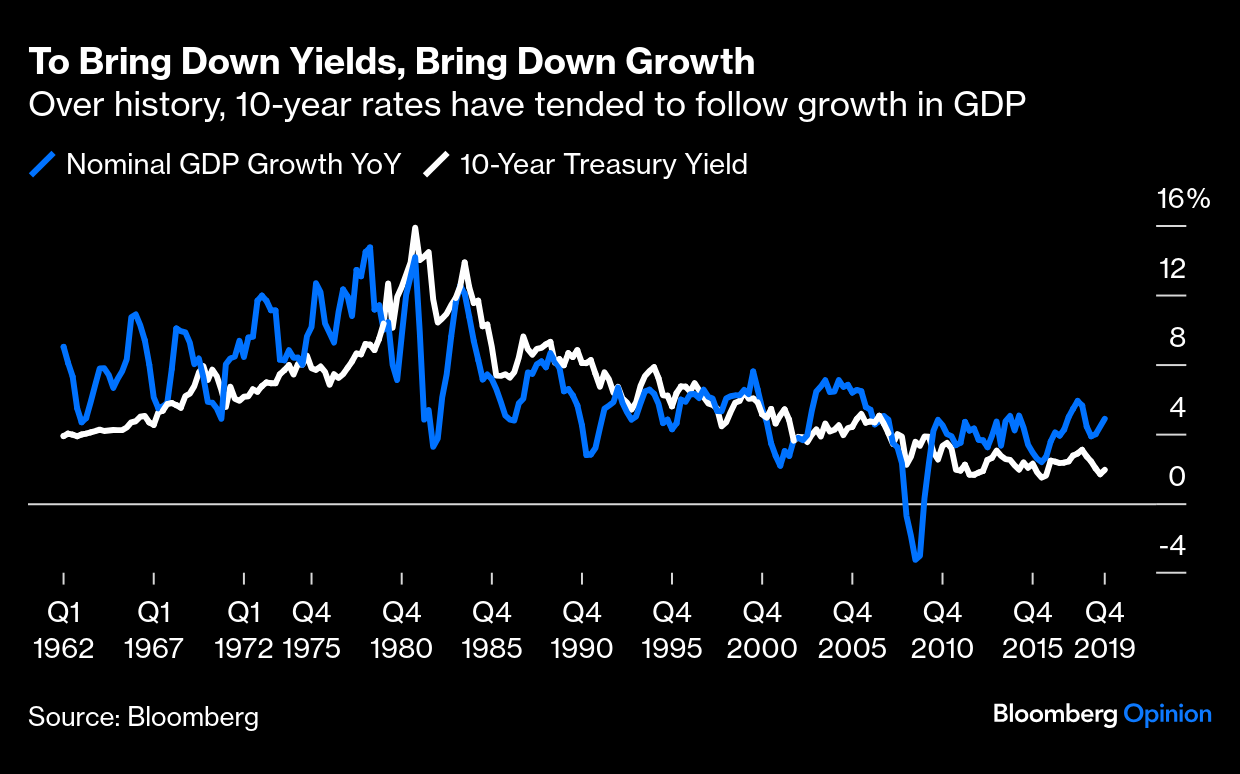

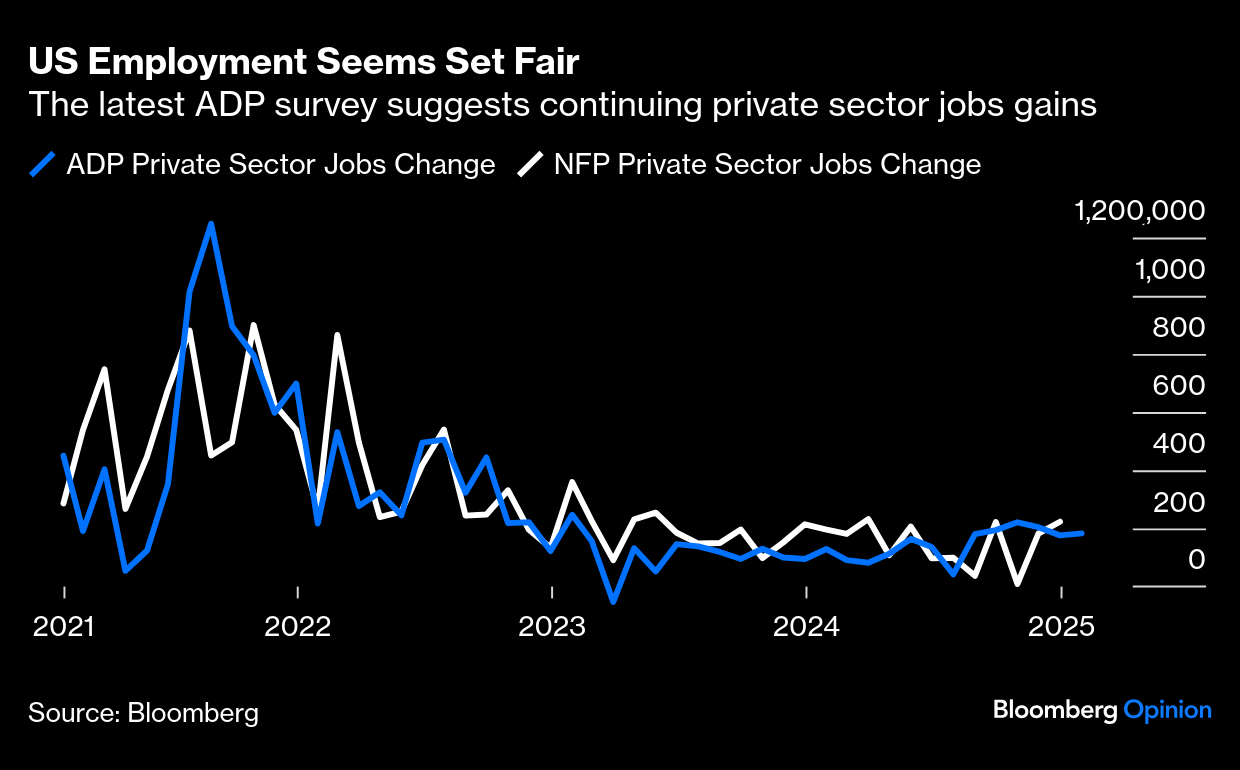

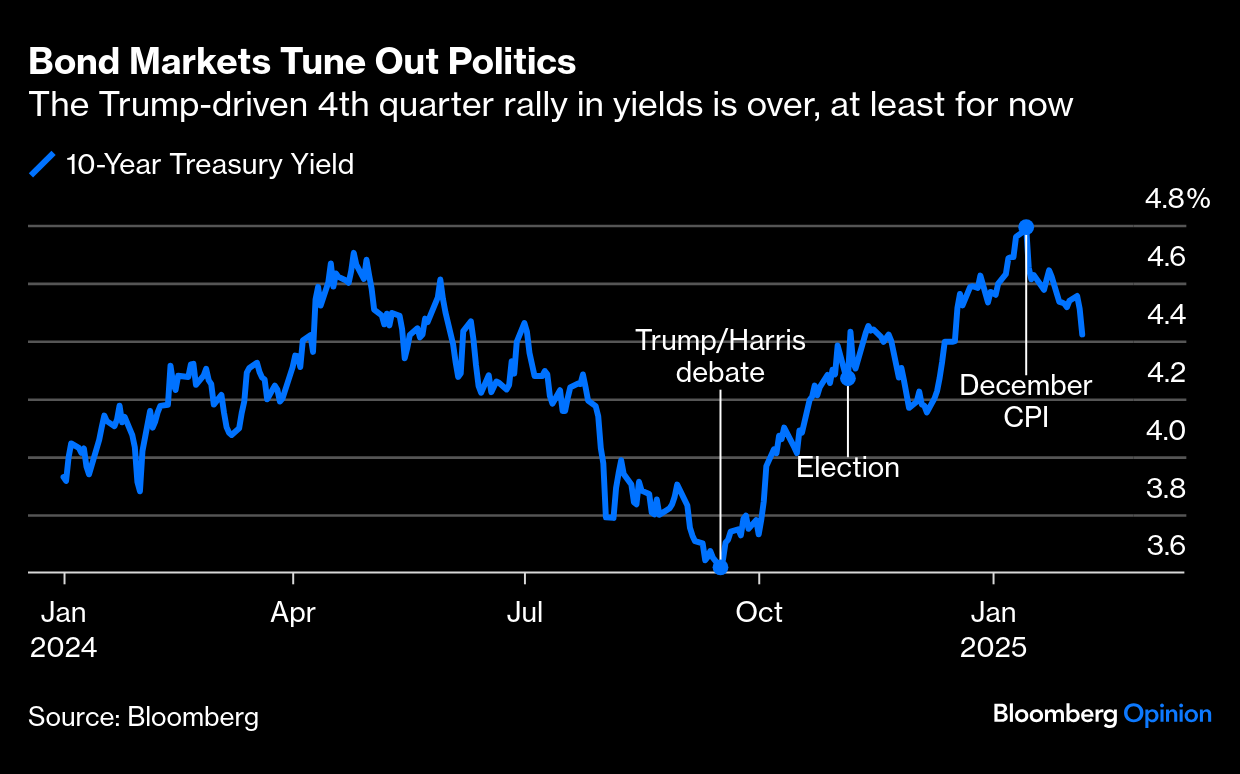

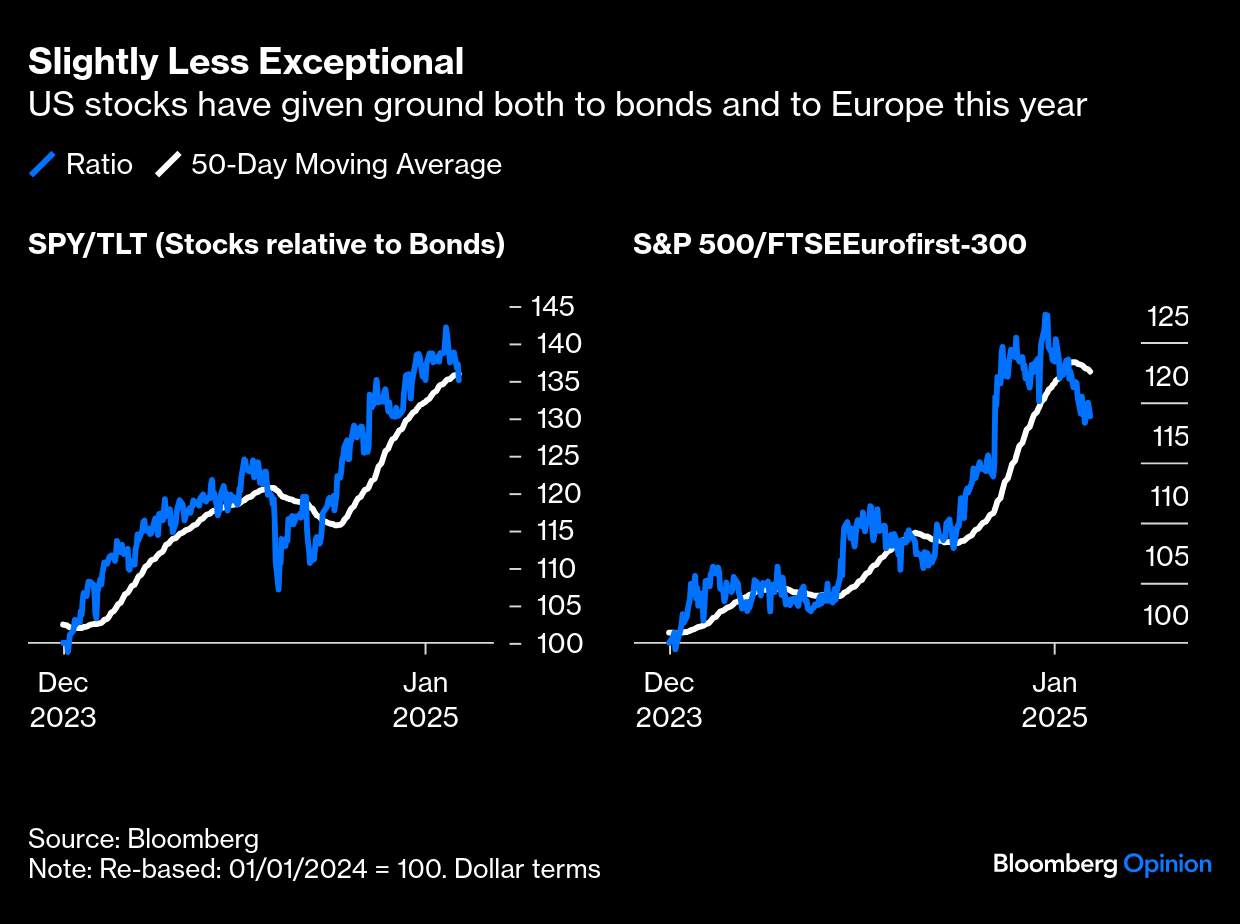

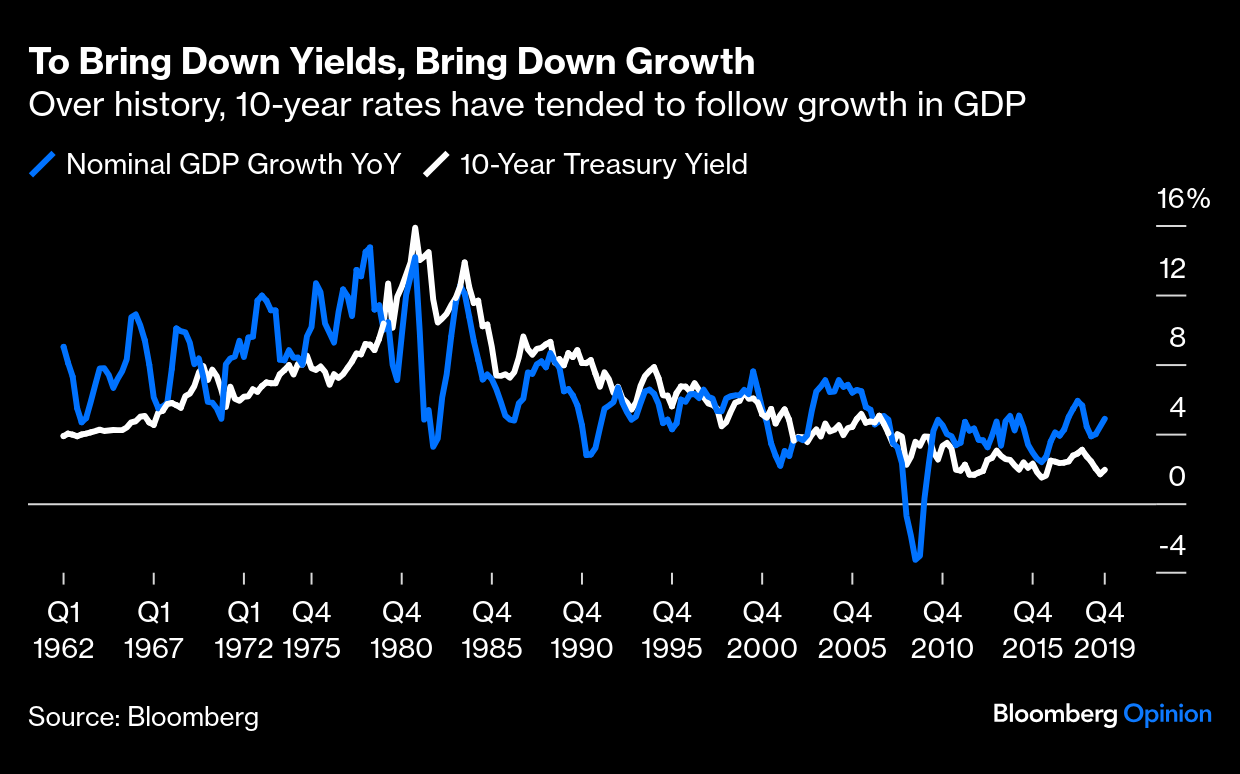

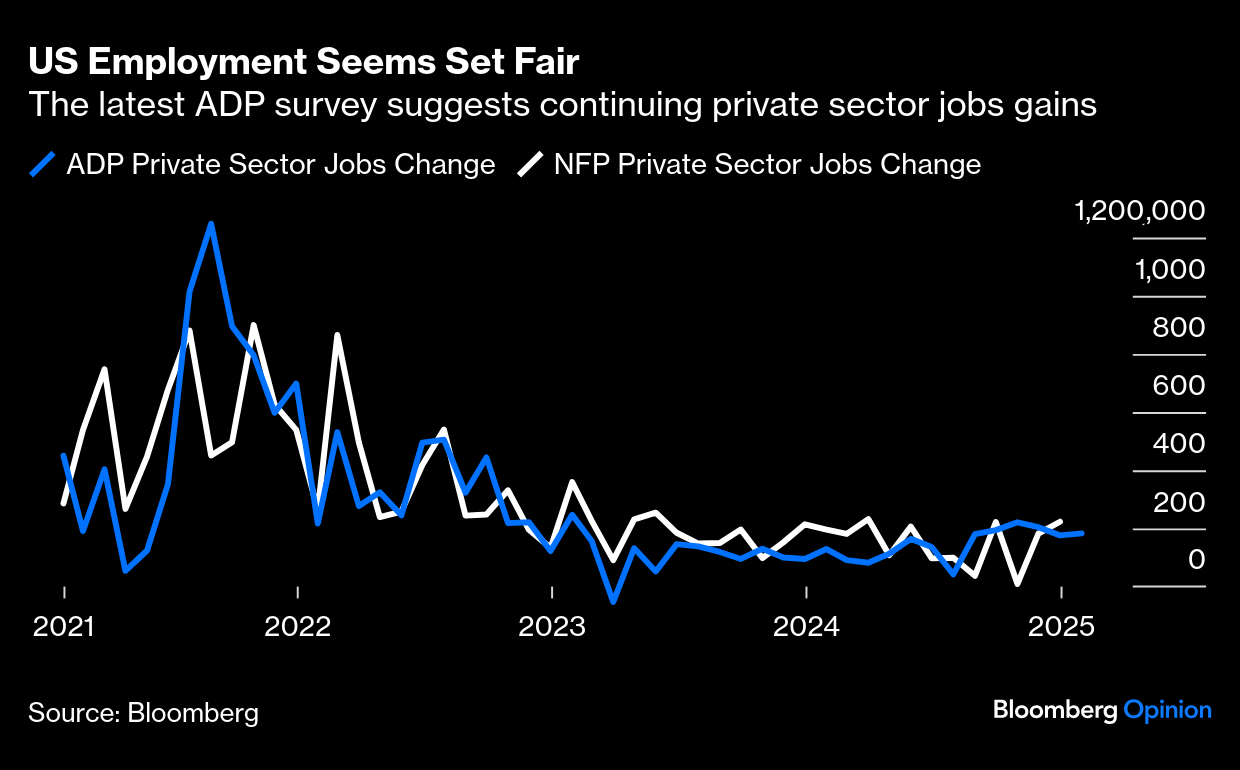

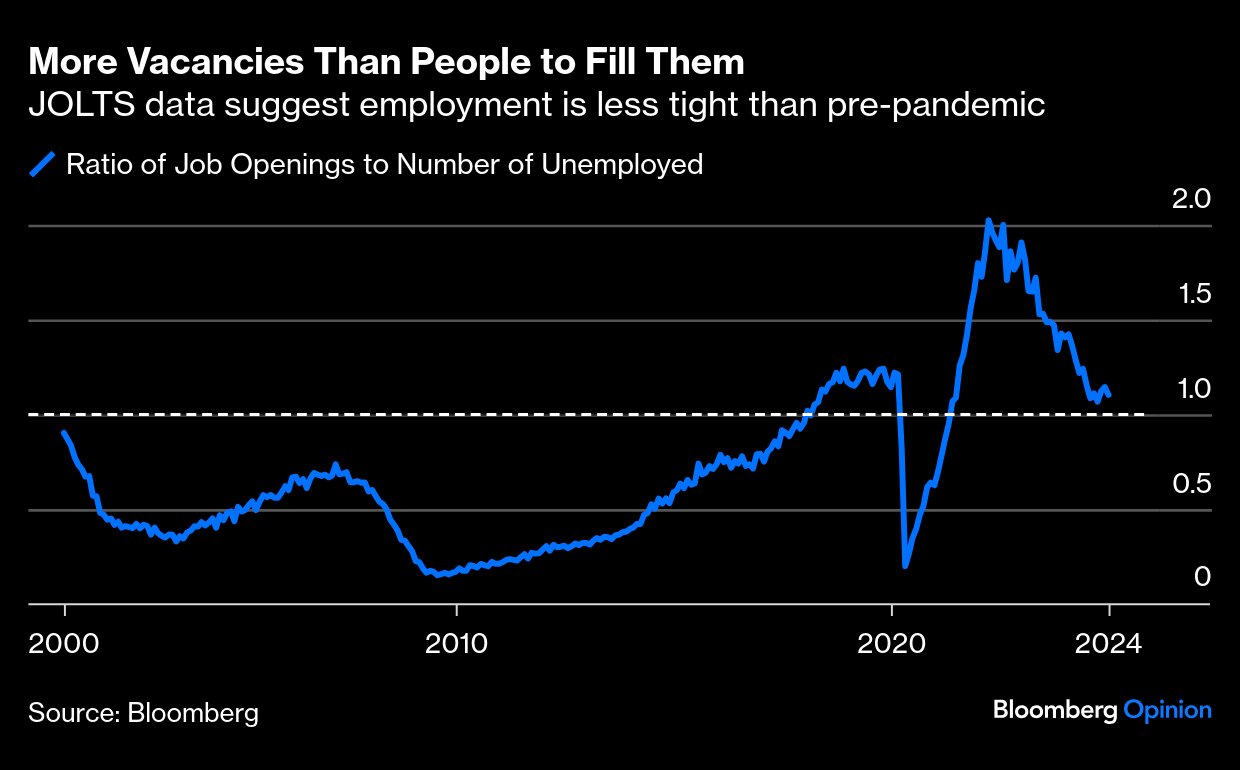

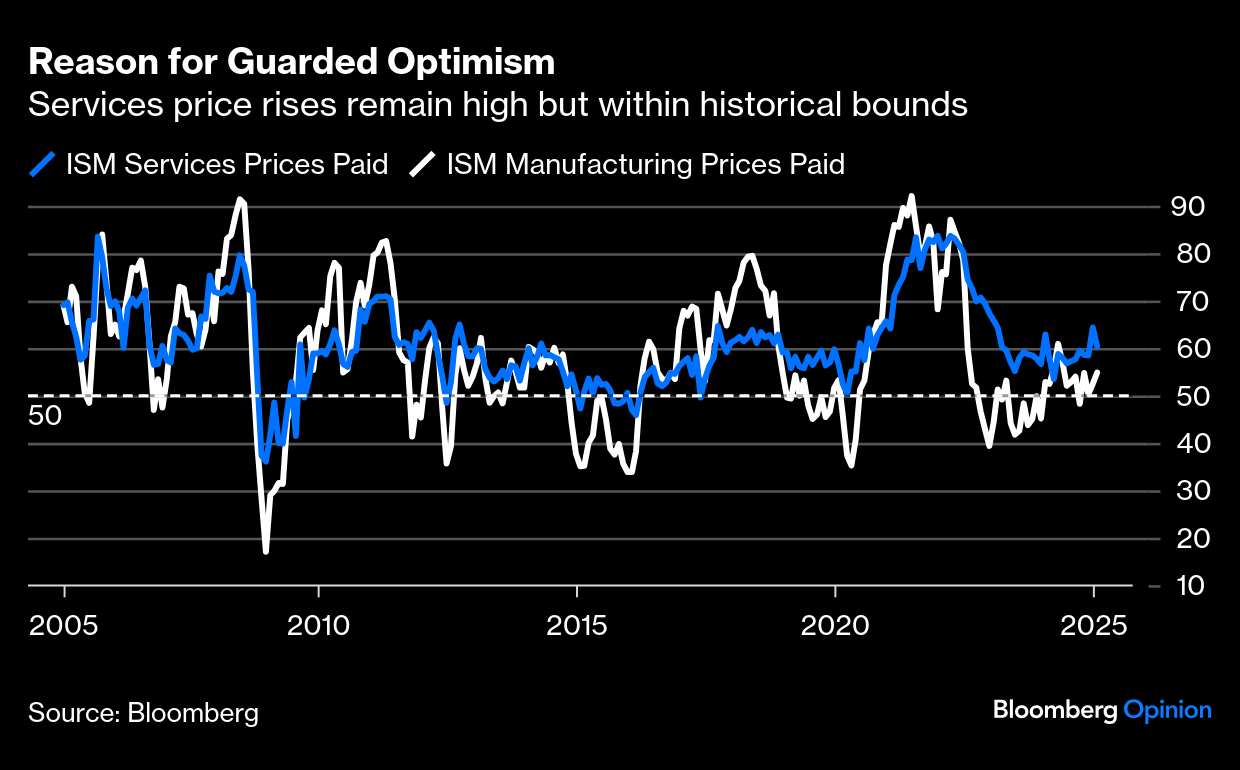

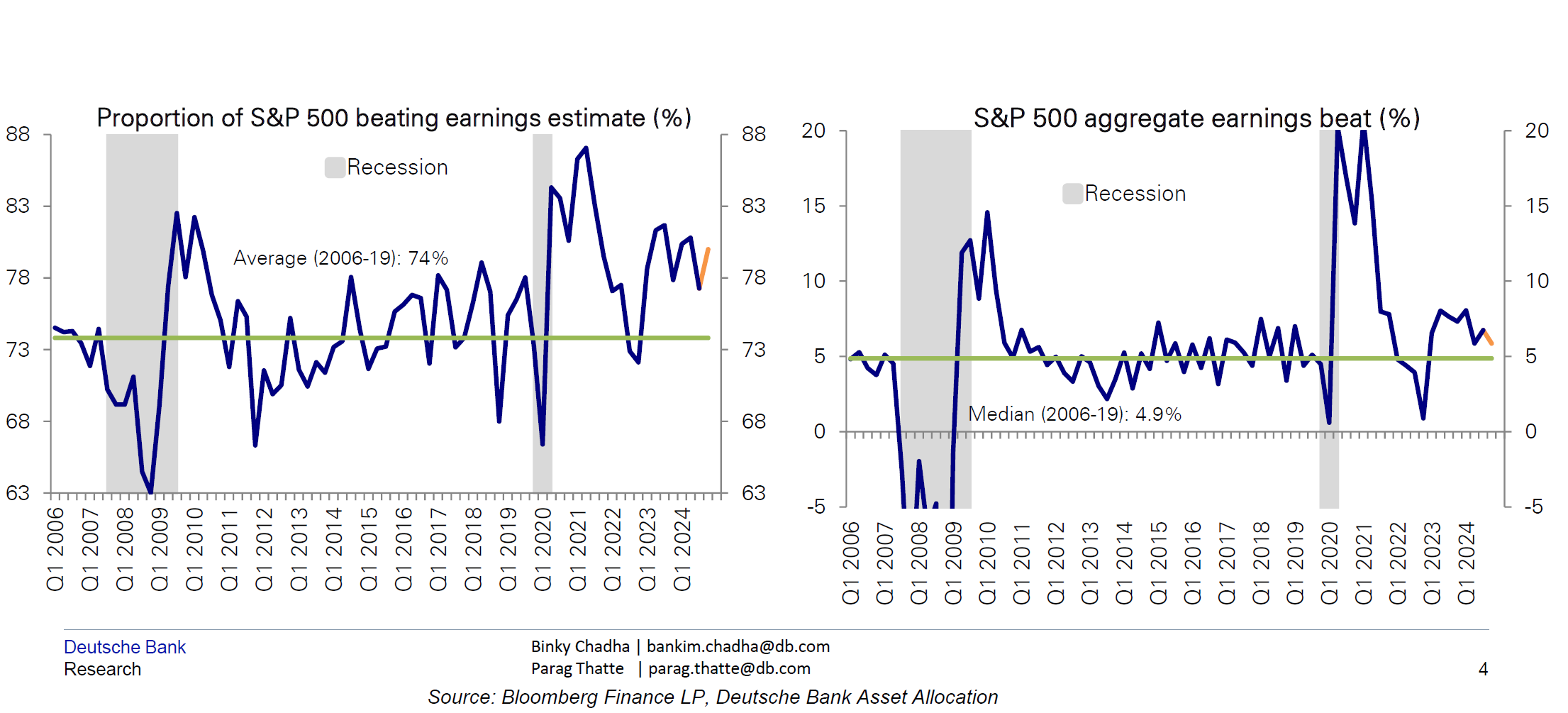

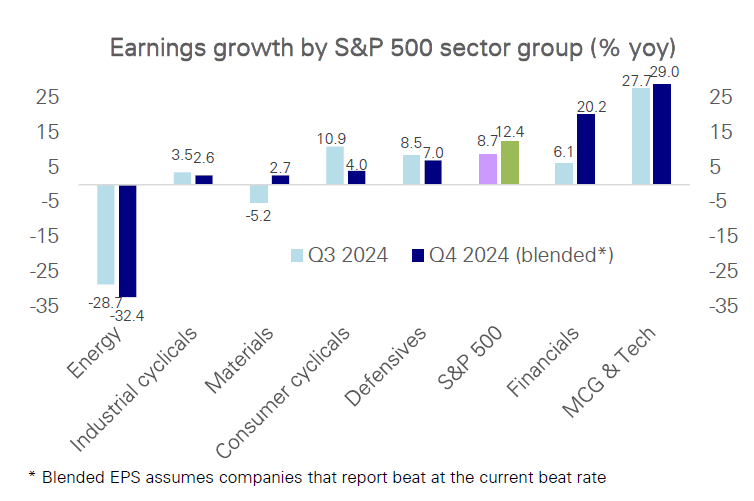

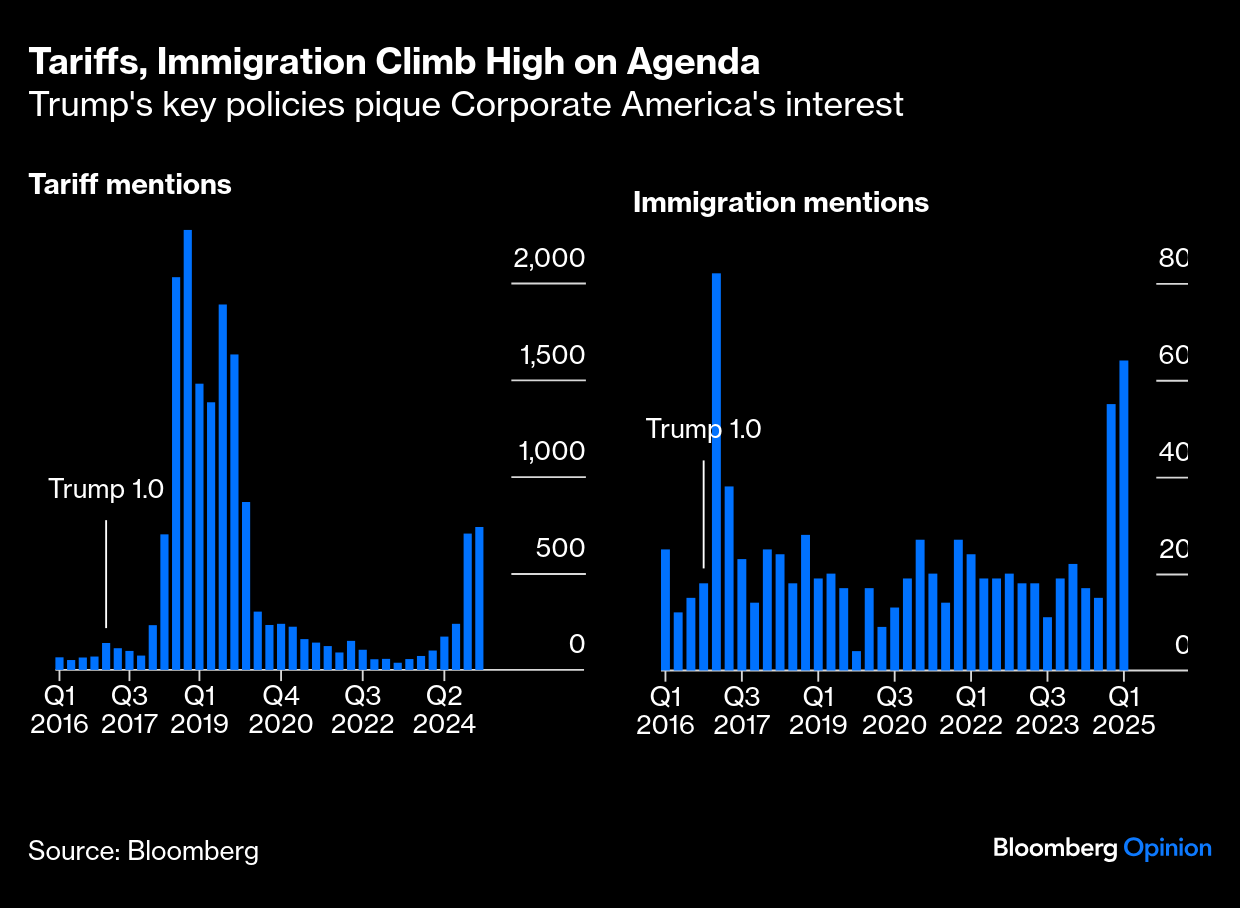

This makes sense as the 10-year benchmark is the most important rate in the entire global economy, and elected politicians should keep their hands off an independent central bank. The problem is that nobody controls the Treasury yield — it's set by one of the world's biggest and most liquid markets. In the years before the Global Financial Crisis, Alan Greenspan's Federal Reserve famously tried to push up the 10-year yield and couldn't. It became known as the conundrum. To keep yields down, central banks and governments can buy industrial quantities of bonds — the dreaded quantitative easing, a policy that amplified inequality to excruciating levels and that nobody wants to repeat. Bessent also has to contend with the almost universal belief on markets that Trump 2.0 means higher 10-year yields. The argument is that tax cuts will mean higher deficits and higher yields to finance them, while tariffs will raise inflation. That brings higher yields in its wake. Thus yields rose sharply during the last quarter of last year, from a low in the brief period around the president's debate with Kamala Harris when his chances looked to be weakening. It's natural that the administration wants lower rates, the argument goes. Who wouldn't? But their agenda will make it mighty difficult to achieve. And yet. Bond yields are falling. The 10-year has shed 40 basis points in barely a month. And despite every other headline as the new president behaves like a bull in a china shop, the big bond market event of the year so far was the December inflation data. Nothing else comes close: That was the decisive turnaround, even though the inflation data wasn't that exciting. Disinflation is happening painfully slowly. However, the numbers were quiescent enough to dispel the notion that price rises were already resurging, and the Trump Trade had been overdone. Since then, traders reacting to his actions rather than his words have continued — with occasional interruptions — to step back from bets on rising rates and inflation. In the process, they've also stepped back from bets on American Exceptionalism. Relative to long Treasuries (proxied by the TLT exchange-traded fund), the S&P peaked on inflation day and has now dipped below its 50-day moving average. The post-election rally went a bit too far, and now it's over. Relative to Europe, the US market enjoyed a massive post-election rally, which peaked in December and is now reversing. Not only have traders lost their conviction about higher inflationary pressure, but they're less convinced that the administration will go through with significant tariffs against the European Union: So if big tariffs become a reality, the bond market could reverse. For now, the administration is benefiting from a belief that it doesn't mean what it says. In the longer term, Bessent and Trump face an even greater obstacle to pushing down the 10-year yield while growing the economy. Over history, the best way to reduce yields has been to bring down economic growth:  On that subject, and with the bond market beginning to shift, we now approach a familiar ritual. US unemployment data is due Friday. The key audience will be in the Federal Reserve, rather than the White House. The assumption is that the jobs numbers will do nothing to persuade it to move interest rates either up or down, and the week's data download has so far supported that. The estimate of private sector jobs from the payroll group ADP, which tends to be less volatile than the official number, suggests that the economy continues to produce an average of a bit less than 200,000 jobs each month, as it has for two years now:  That follows the JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) for November. After the pandemic, vacancies ballooned so there were as many as two empty spaces for each unemployed worker, a situation that fueled wage rises and inflation. The huge swings caused by Covid now appear to have calmed, with still slightly more than one available worker for each job. This is above the historical norm, but below the ratio reached in 2019. At such levels, there's no obvious need for rate cuts: The ISM supply manager surveys for January also suggest a level of inflationary pressure that makes it hard to justify shifting monetary policy in either direction. The services sector prices paid index, which proved a great early warning of inflation back in 2021, dropped but remains elevated, while manufacturing prices also ticked up. Again, this indicator seems totally in line with a prolonged Fed pause: All of this suggests that the US economy is in something like a sustainable equilibrium in which there will be no need for higher rates from the Fed or dramatically higher yields on 10-year Treasuries. The question is whether Trump 2.0 policies will disturb that equilibrium. Earnings season has provided some evidence. Levying US Exceptionalism | Fourth-quarter earnings season is going according to plan. The Sputnik-like arrival of DeepSeek naturally focused attention on mega tech companies, whose results have been mixed, but beyond them there is corporate resilience. And they are playing the game of earnings management better than ever, getting Wall Street to set targets for them that they can beat. Deutsche Bank AG's Binky Chadha estimates that 80% of S&P 500 companies topped their earnings estimates, more than the 74% historical average. The size of the aggregate beat, 5.9%, and the beat by the median company, 4.1%, are also above historical averages. Strong performance is broad-based, with financials and consumer cyclicals recording double-digit beats. Sectors like materials, industrial cyclicals, energy, mega-cap growth, and tech are ahead of estimates by mid-single-digit rates. Defensive stocks are more modest: Importantly, with the exception of energy, all sectors are recording earnings growth, and banks are on course to outstrip third-quarter growth: The discussions on earnings calls, and what they reveal about executives' thinking, perhaps matter more — particularly amid the upheavals of Trump 2.0. A search of earnings transcripts reveals that tariffs shenanigans are getting a lot of attention as companies weigh the consequences and seek workarounds. Tariffs hadn't been as topical since 2018, when Trump 1.0 made punitive levies against China. Meanwhile, at a much lower level, immigration — and its possible ramifications on inflation and the difficulties it could create for recruiting workers — is also attracting far more comment: The market reaction to the weekend brinkmanship involving Mexico and Canada illustrated the problem as the S&P 500 fell by 2% in Monday's early trading, before the tariffs were postponed. Apollo Global Management's Torsten Slok explains Corporate America's apprehension: When you have an already strong economy with strong GDP growth, with too-high inflation, and you layer on top of that a trade war with higher tariffs, the consequences complicate the job by the Fed. It makes it much more difficult for the Fed to cut interest rates and it increases the risk that it potentially may have to hike rates later this year.

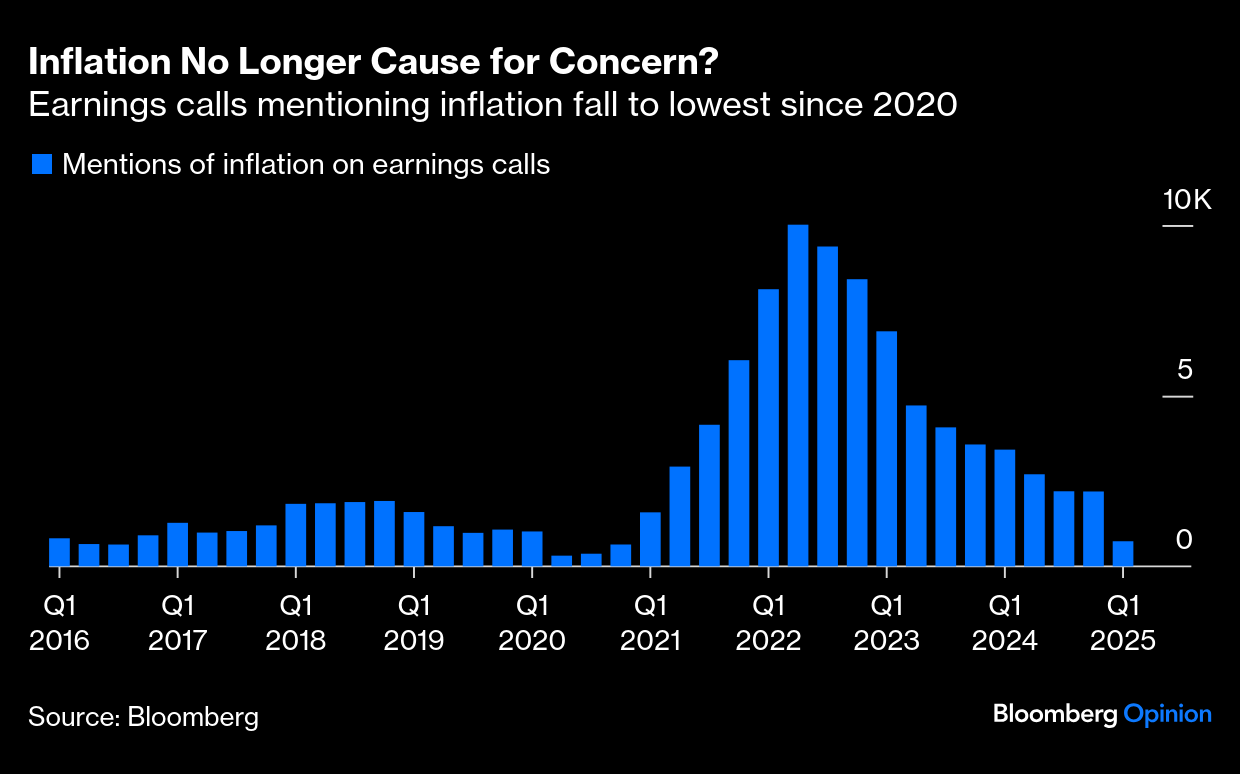

Despite Bessent's thumbs-up on the Fed's pause, the administration wants bond yields to fall, while companies and investors alike believe protectionism is inflationary (and would thus raise yields). That's a shame, as executives' mentions of inflation have dropped back below levels seen before the pandemic, suggesting that they tend to believe the problem is over: As Gavekal Research's Tan Kai Xian points out, tariffs — if imposed and maintained — would act like a bucketful of sand in the wheels of the global economic machinery. Companies have had time to prepare by frontloading inventory builds and diversifying supply chains, but tariffs would still be disruptive and impose significant extra costs. The US should fare better in a full trade dispute because of its relatively closed economy, but Xian cautions: This overlooks the interplay between the US stock market and the US dollar. A steep fall in US equities in response to tariffs might well dampen foreign investors' enthusiasm for holding US stocks. More to the point, a steep fall in US equities would blow a hole in US households' net worth. The entire increase in US net wealth since 2022 is attributable to higher equity prices. So, if US households respond to a fall in equities by curtailing their consumption in order to save more of their earnings, growth in the highly consumer-dependent US economy would suffer.

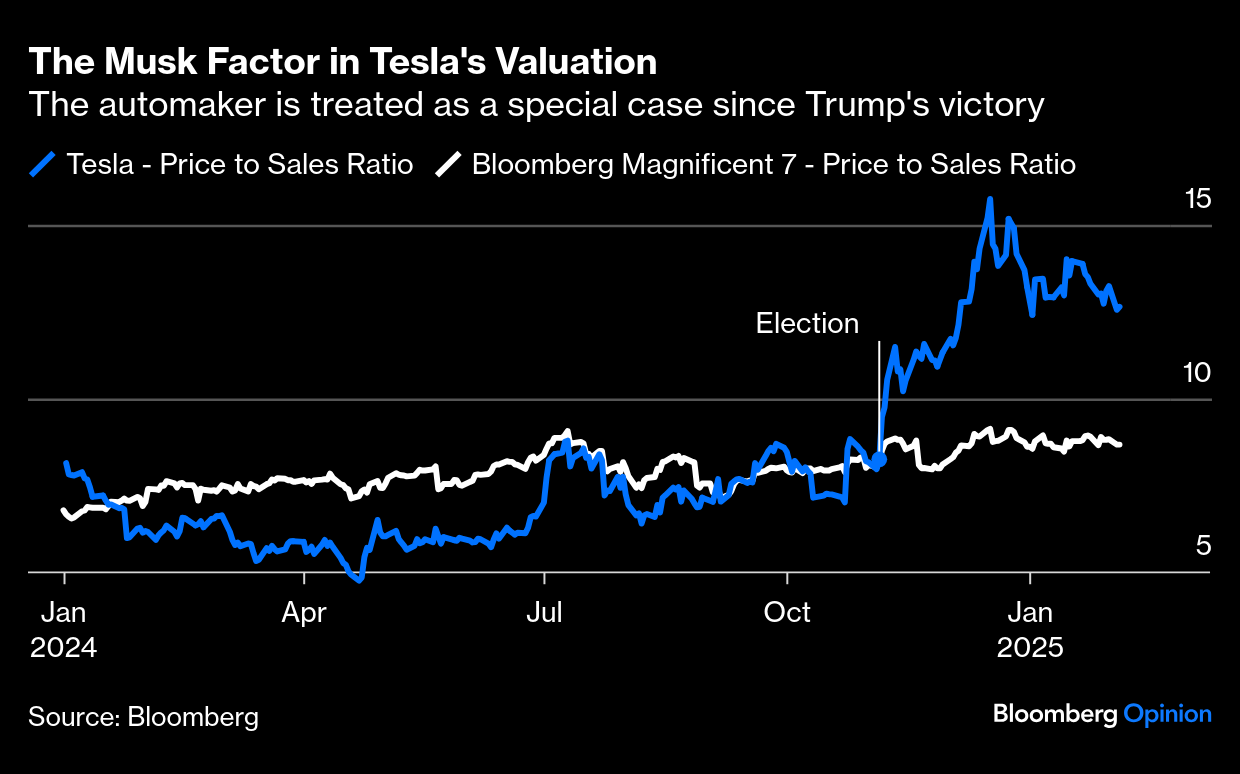

A steep fall in US equities is also what the new administration badly wants to avoid, while an exit of foreign investors would make it much harder to keep the lid on bond yields. After the climbdown on Mexico and Canada, the assumption appears to be that Trump 2.0 doesn't mean tariffs any more drastic than in his first term. That's allowing bond yields to come down and helping the growth agenda (while disappointing the many who had bet on more US exceptionalism and higher yields). Moving ahead with tariffs could make Bessent's life much more difficult. —Richard Abbey How do you solve a problem like Elon? Whatever you think about the world's richest man, his closeness with Trump and the influence he currently wields in the US government might well have a big impact on his company's fortunes. Putting a valuation on that Musk Factor now is more or less impossible, but markets are trying. This is Tesla's price-to sales multiple compared to that of the Magnificent Seven as a whole since the beginning of last year: As Liam Denning commented for Bloomberg Opinion, Tesla is a car company, but its stock has become a meme. Musk's rampage through the federal bureaucracy is quite a saga. He is being left to police his own potential conflicts of interest. The investors who hold shares of the different parts of his empire have almost as much at stake as he moves fast and breaks things. The family have been watching the documentary celebrating 50 years of music on Saturday Night Live. It's brilliant. Highlights include Beef Baloney by the punk band Fear in 1981, a punk band reunion at a wedding, featuring Dave Grohl, Ashlee Simpson caught lip-syncing, Rage Against the Machine who wanted to hang an upside-down Stars and Stripes and went on to pick a fight with the host, presidential candidate Steve Forbes, Elvis Costello changing the song, and a young Taylor Swift's monologue song. Everything goes better with more cowbell. And then there was that moment with Sinead O'Connor. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Marc Champion: Trump's 'Gaza Riviera' Scheme May Be More Than a Fantasy

- Juan Pablo Spinetto: Pemex Needs Radical Surgery, Not More Painkillers

- F.D. Flam: How Conspiracy Theories Took Hold of America

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment