| I'm Molly Smith, an editor in New York. Today we're looking at US inflation. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. - Bank of Japan officials see a good chance of an interest rate hike next week.

- Scott Bessent will state the case for keeping the dollar as the world's reserve asset today when he addresses the Senate for confirmation as US Treasury secretary.

- Britain's economy narrowly returned to growth in November but fell short of expectations.

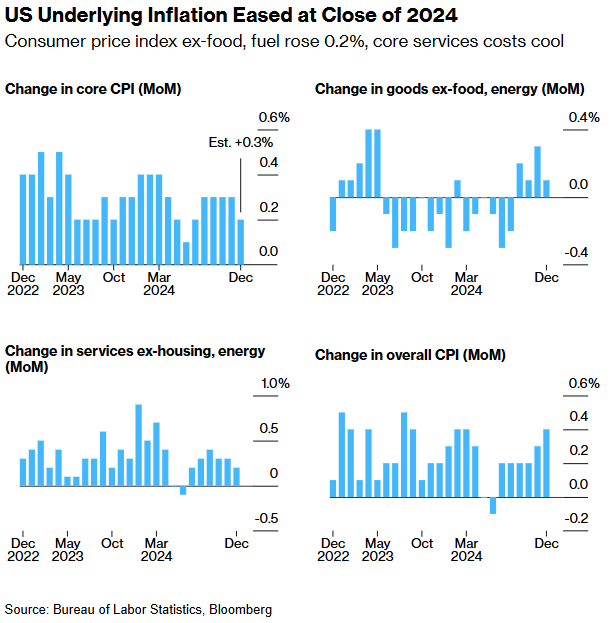

Another day, another CPI report, and another shift in how economists and the markets think inflation progress is actually going in the US. After months of elevated readings, the core consumer price index — which excludes food and energy — finally eased in December and restarted the conversation that inflation is indeed cooling, albeit at a glacial pace. Stocks and bonds rallied, with several economists predicting the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates as soon as March — much earlier than previously thought. If this feels like déjà vu, that's because it is. Policymakers and investors have been lulled into this thinking before. Core inflation stepped down dramatically through the middle of last year, only to rear back up and fuel concerns that the Fed cut rates too quickly. The other all-important piece to consider are views on the job market, which have also gyrated in the past six months. The labor market now appears to be on better footing than last summer. But that idea could be shaken once again when years of data are revised next month. An early estimate suggested job growth in the 12 months through March 2024 could be marked down by the most since 2009. Donald Trump, who is stepping back into the White House next week, is readying a string of tariffs that are generally expected to put upward pressure on inflation. But for now, markets are content to hold onto the possibility of a rate cut in the first half of this year. "It kind of opens doors a little bit, but it's not really determinative one way or the other," Stephen Stanley, chief US economist at Santander US Capital Markets, said of the CPI report. "We're going to just have to see what the trends are as we move into 2025." The Best of Bloomberg Economics | - China has failed to break a deflationary cycle and is now on track for the longest streak of economy-wide price declines since the 1960s.

- Colombia's president named two academics to the central bank, potentially changing the balance on a board that's split over how fast to cut rates.

- Canada has drawn up an initial list of C$150 billion of US-manufactured items that it would hit with tariffs if Trump decides to levy tariffs against Canadian goods.

- The Bank of Korea unexpectedly held its policy unchanged, opting to stay cool in the face of political turbulence as it also keeps an eye on weakness in the currency.

- Hong Kong's government is exploring options to raise taxes on the city's highest earners for a second straight year to plug shortfalls in its budget.

- Investors are betting that a multi-billion-rand strategy by the government to overhaul South Africa's aging infrastructure will trigger a building boom.

Although inflation rates have come down across the world, pay hasn't fully caught up with the pandemic-related loss of earnings, in part because of weak jobs markets, according to the International Labour Organization. "Global unemployment has remained steady, but real wage growth has picked up only in a few advanced economies with particularly strong labor demand," the Geneva-based body said in its flagship World Employment and Social Outlook report published Thursday. "In most countries, real wages have not recouped the losses incurred during the pandemic years and the inflationary episode that followed." That's partly because bosses have more sway than they used to, the ILO said. Data show that rising market concentration correlates with a shift of labor market power away from workers towards employers, with particularly adverse effects for vulnerable groups and young people. Specifically, labor market concentration seems to have contributed to faster automation without leading to improved labor productivity. |

No comments:

Post a Comment