- Bond yields are attempting a breakout; pay attention, or else.

- It's not just about worries that inflation could return.

- It could be a reaction to reduced long bond issuance under Biden, or show a new secular bear market for bonds.

- In Japan, JGB yields are rising, and the pressure Treasury yields are putting on the yen could force the BOJ into action.

- AND: Some more noise to drown out the signal.

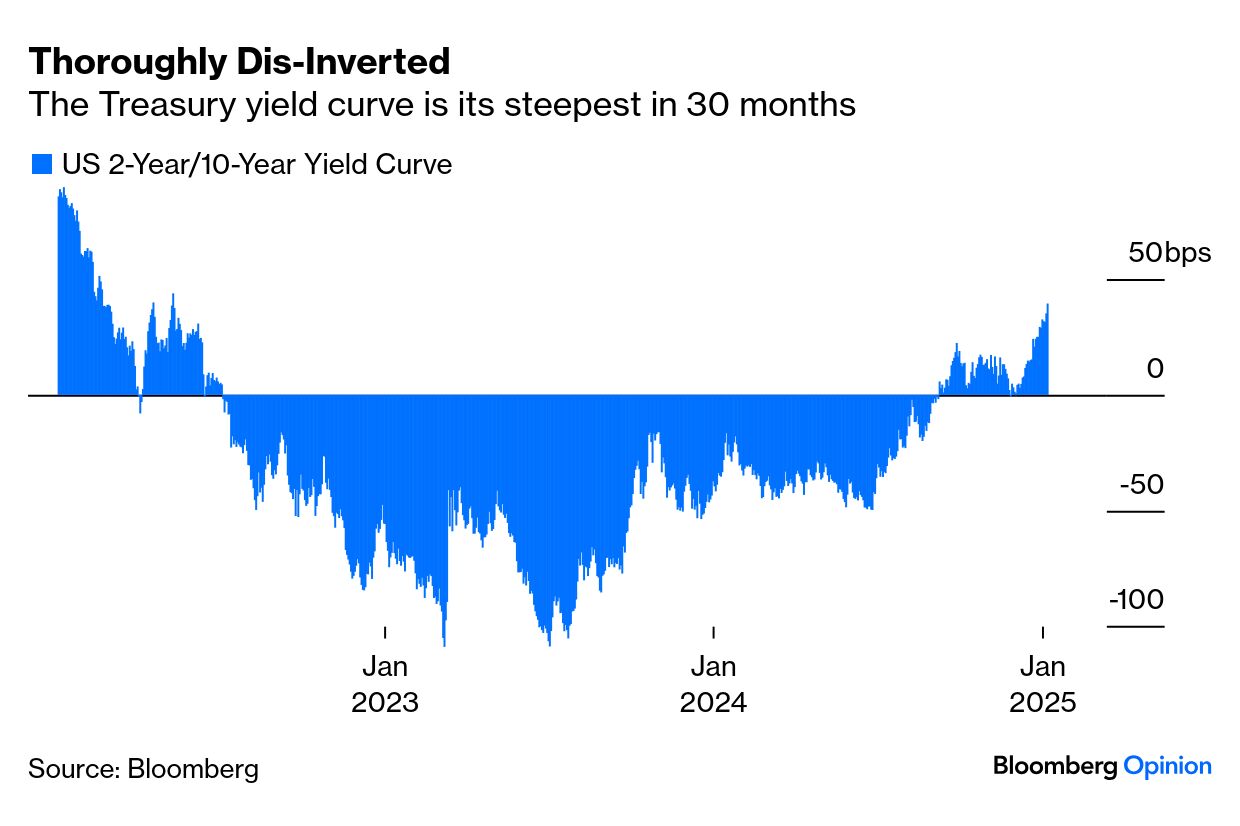

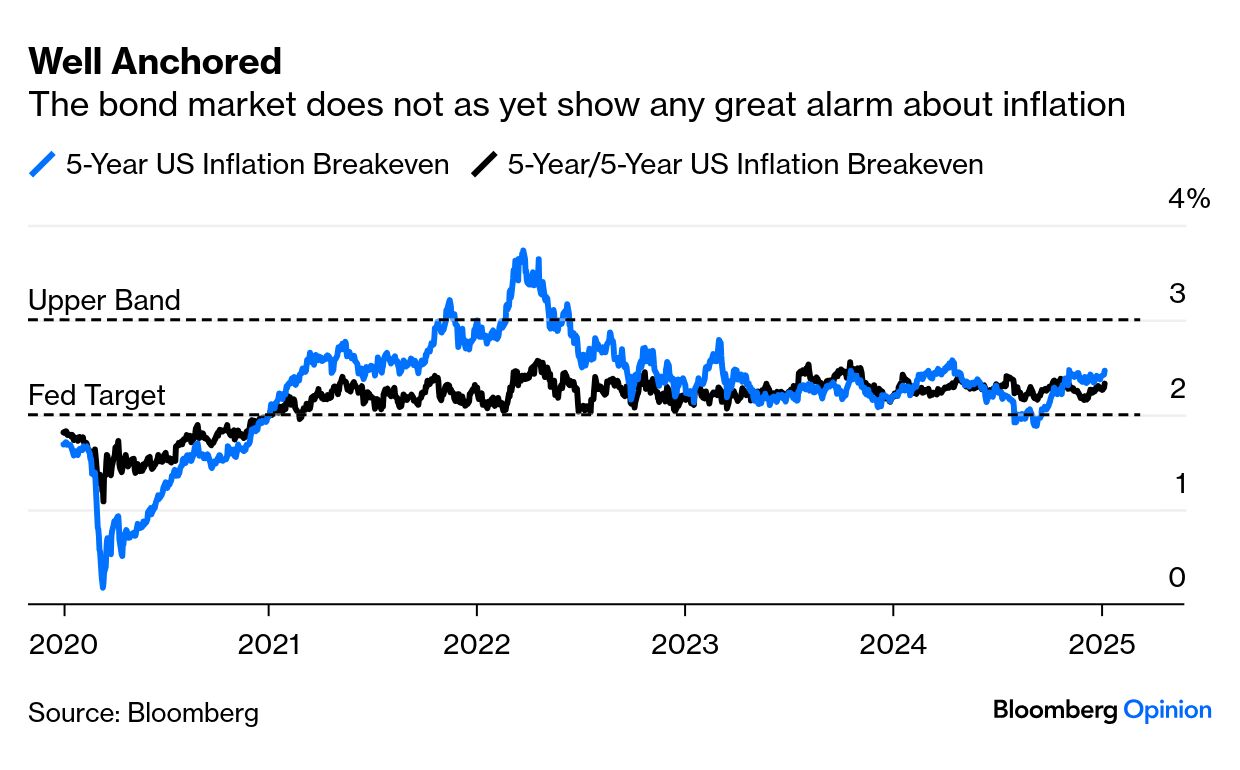

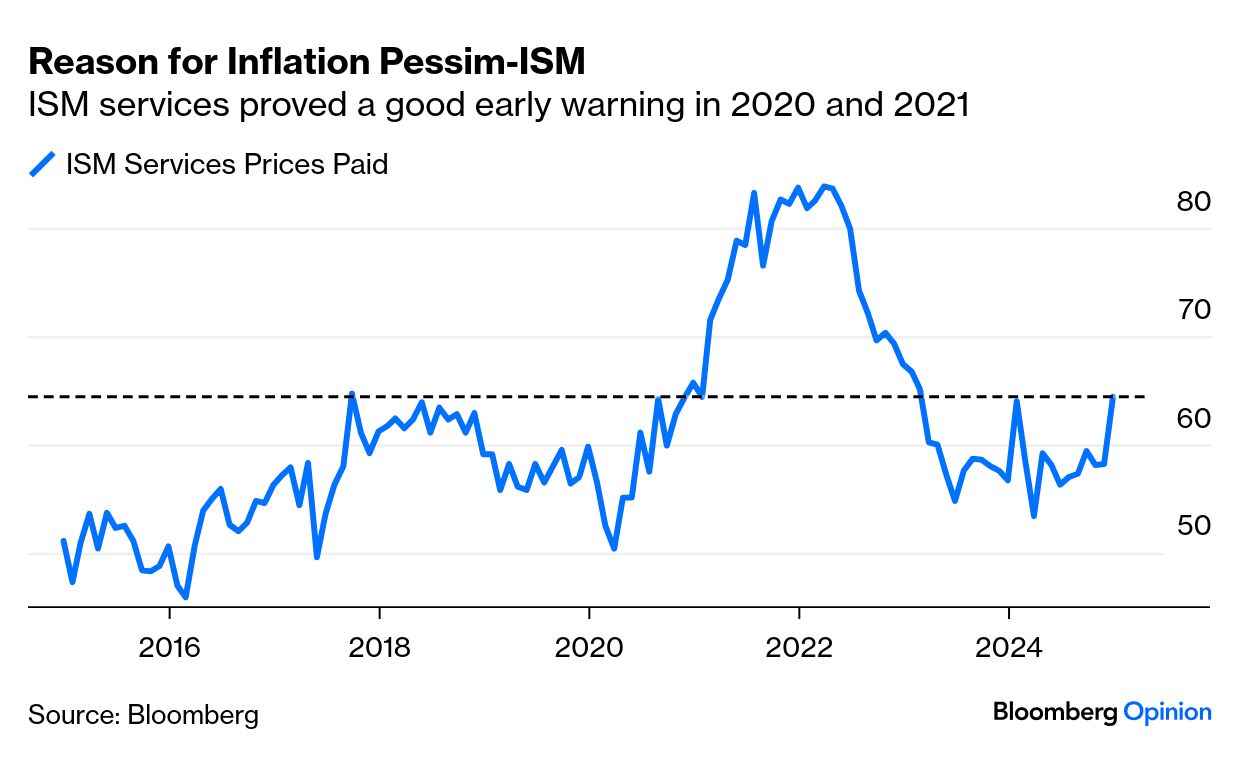

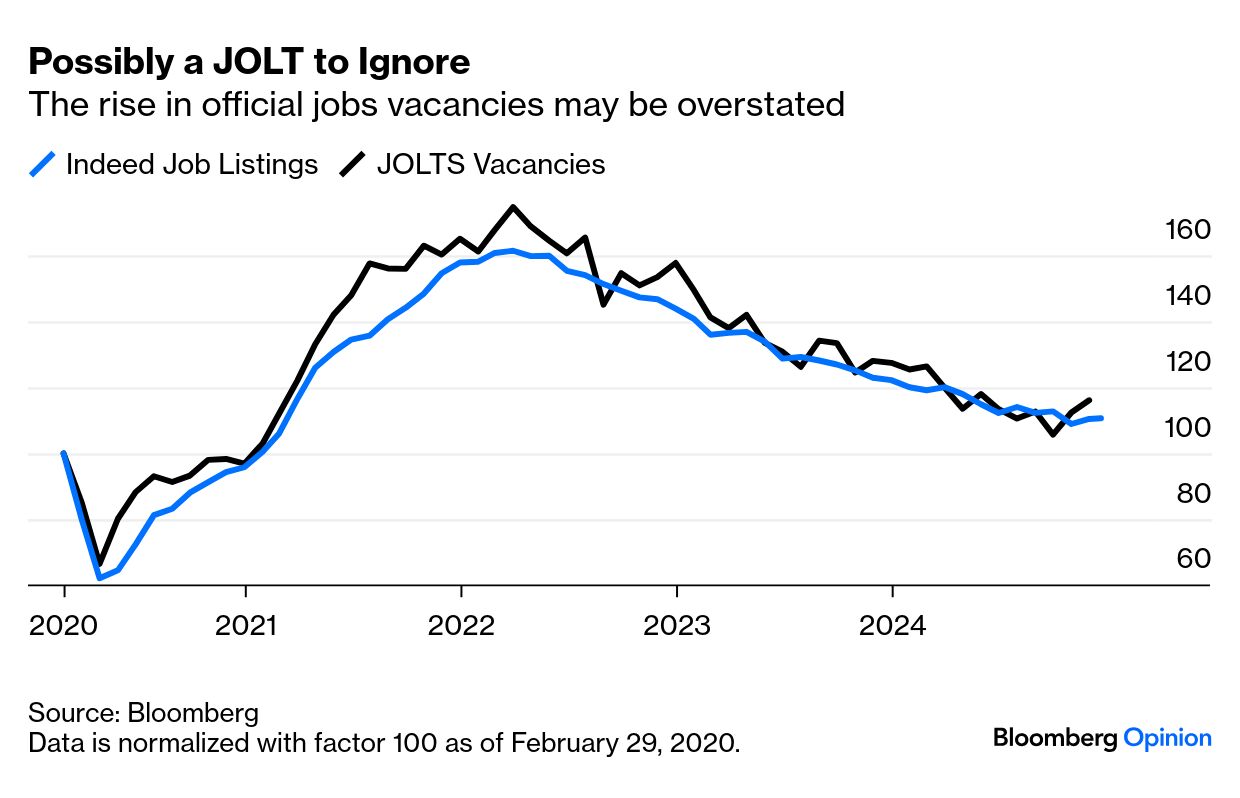

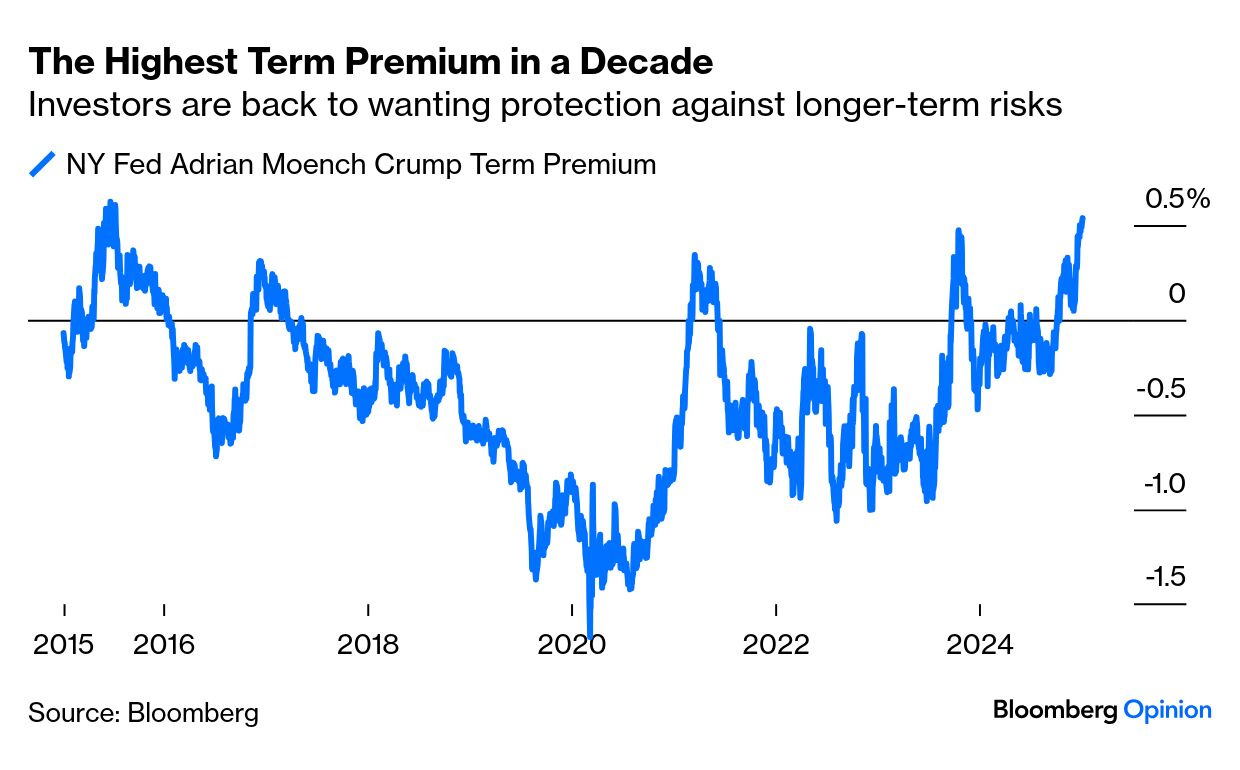

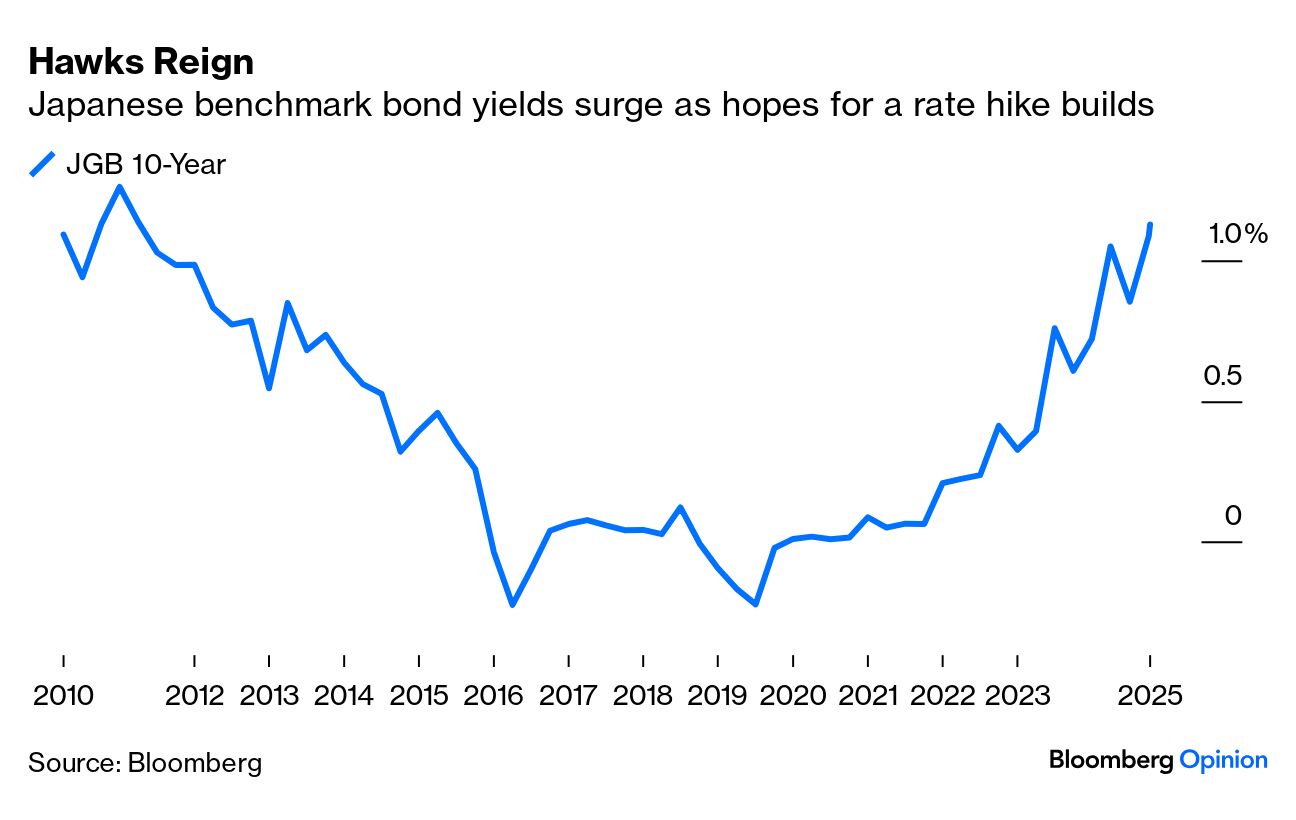

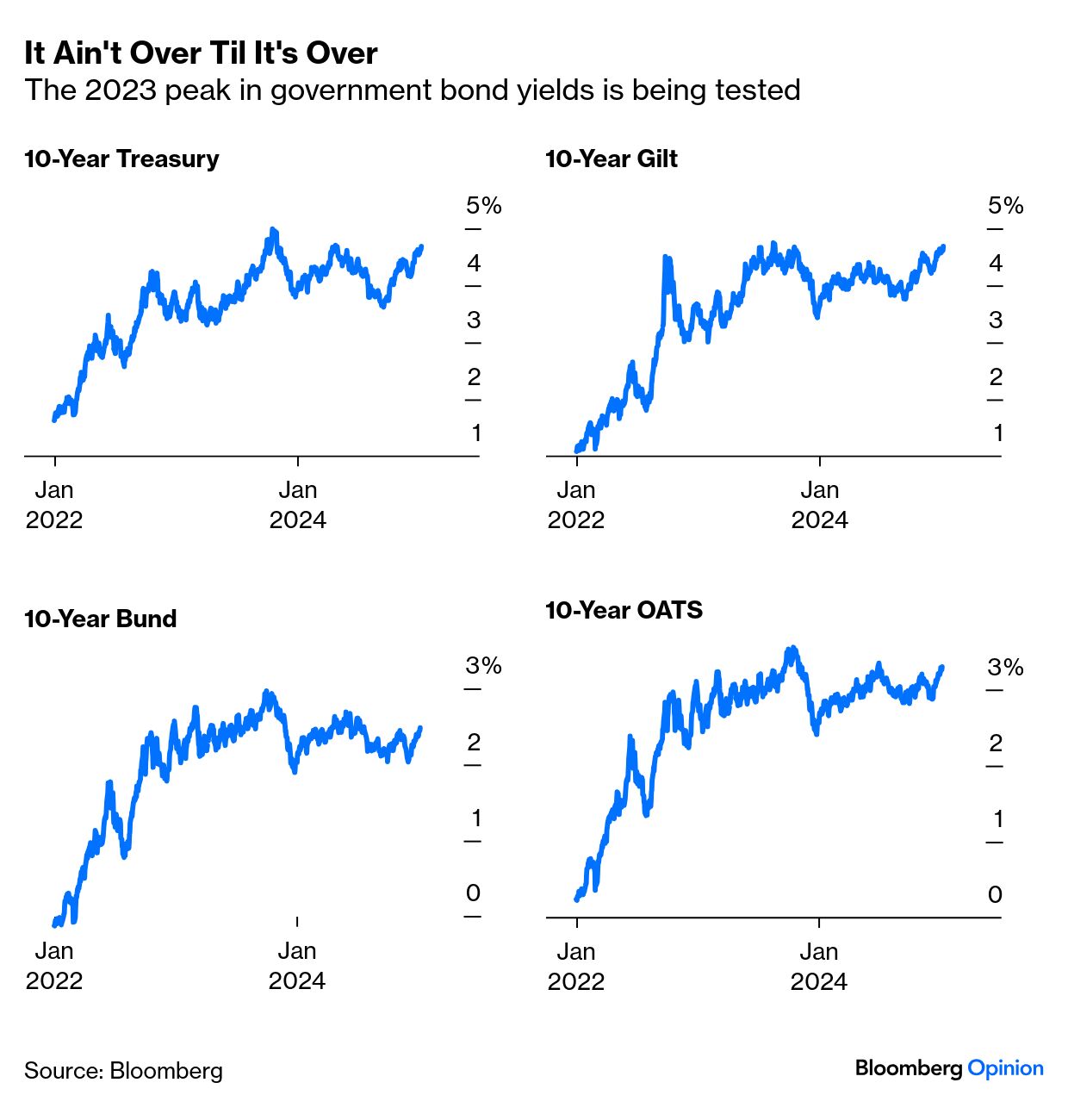

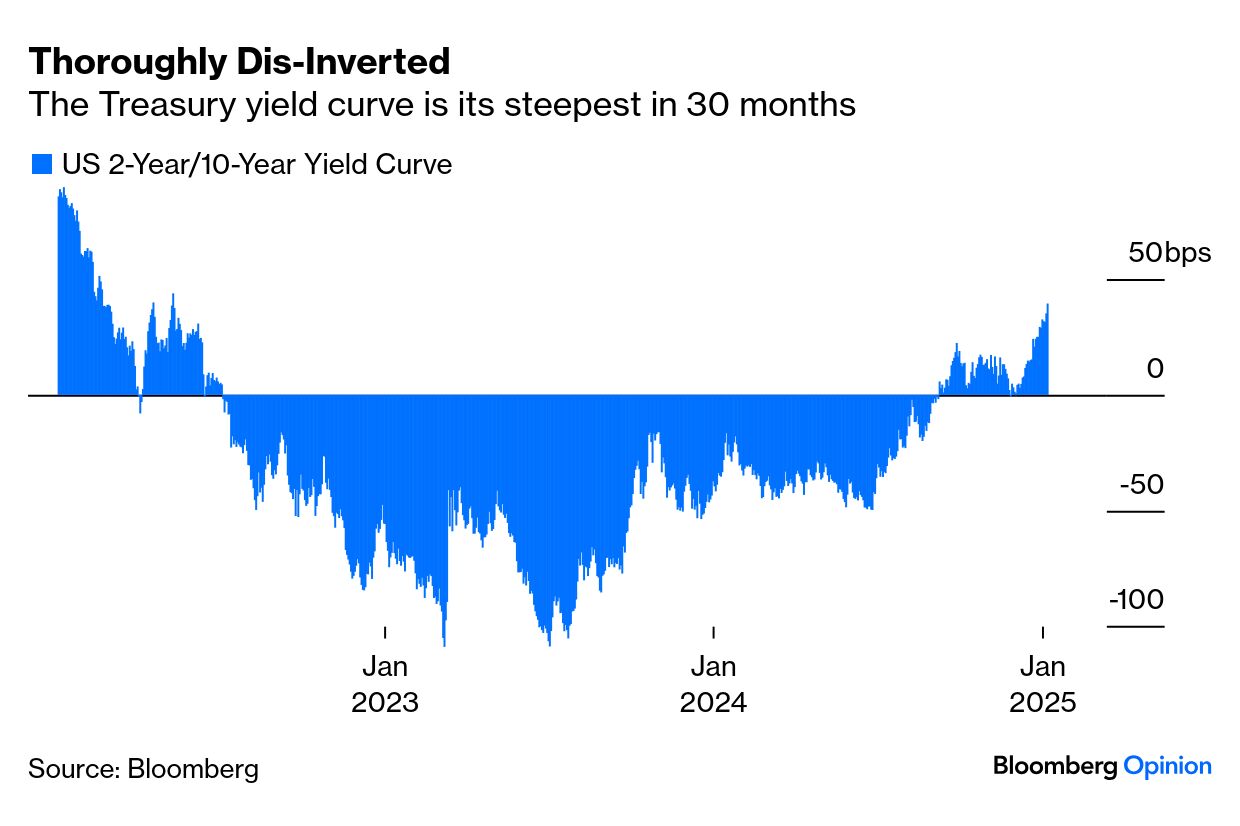

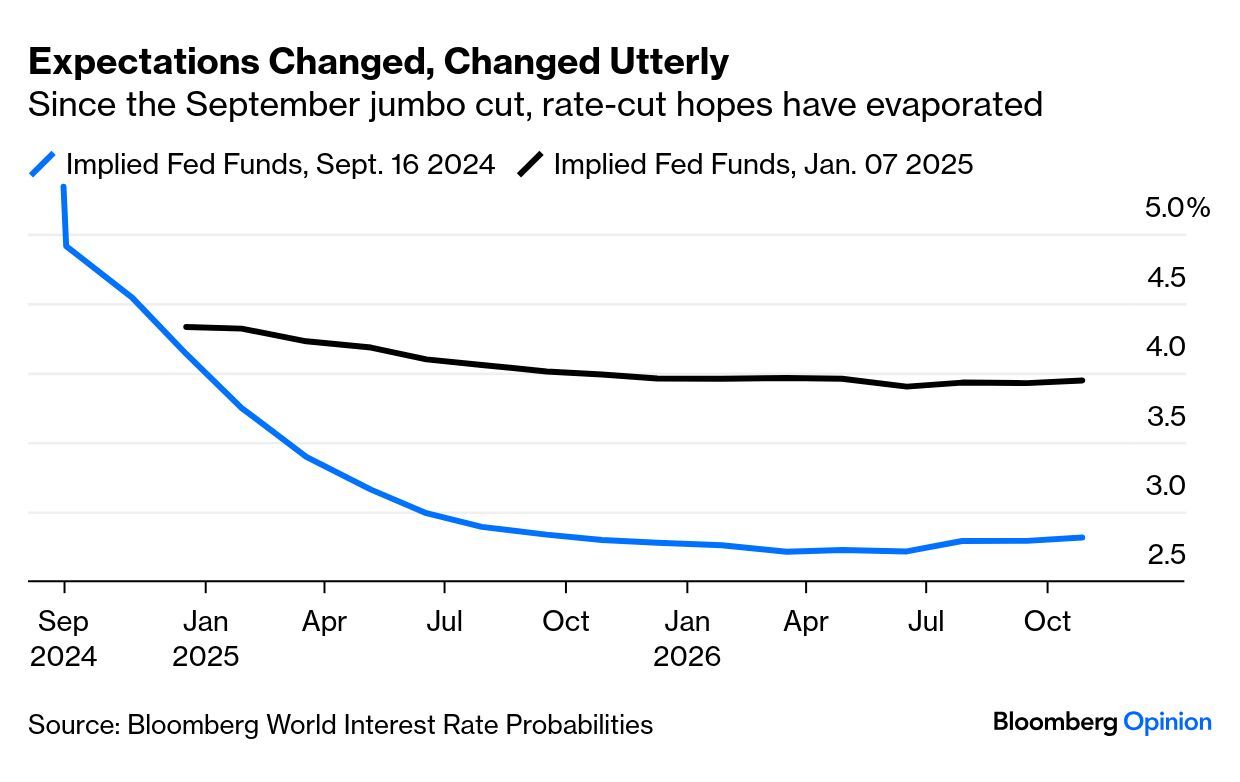

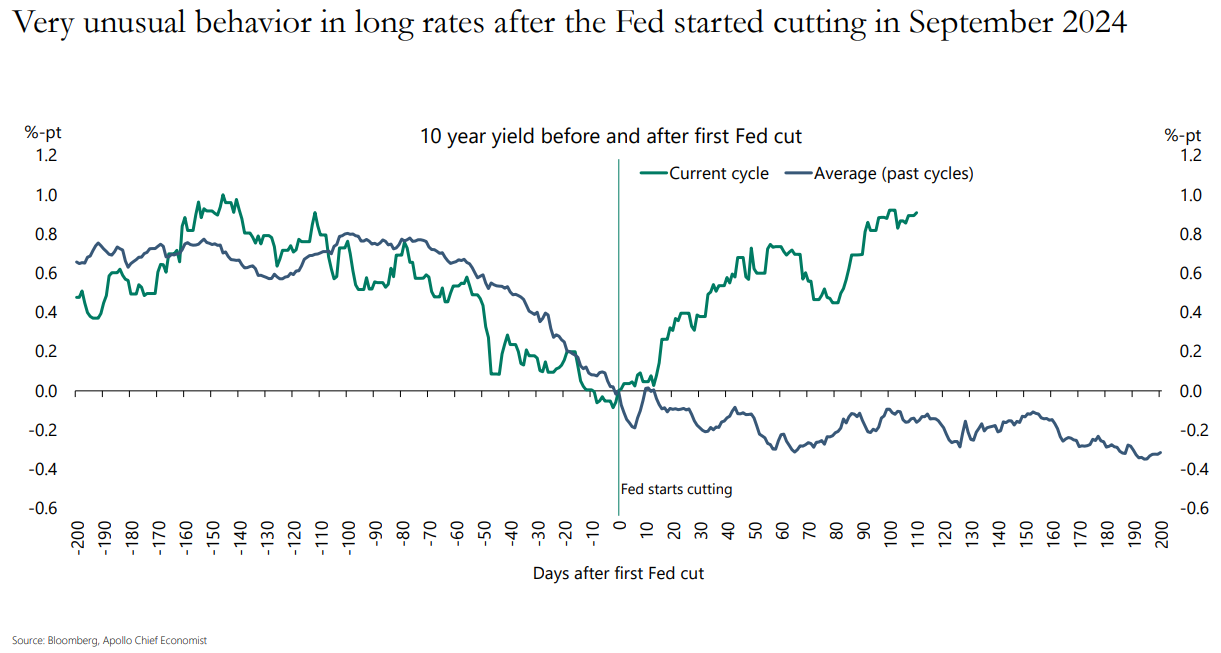

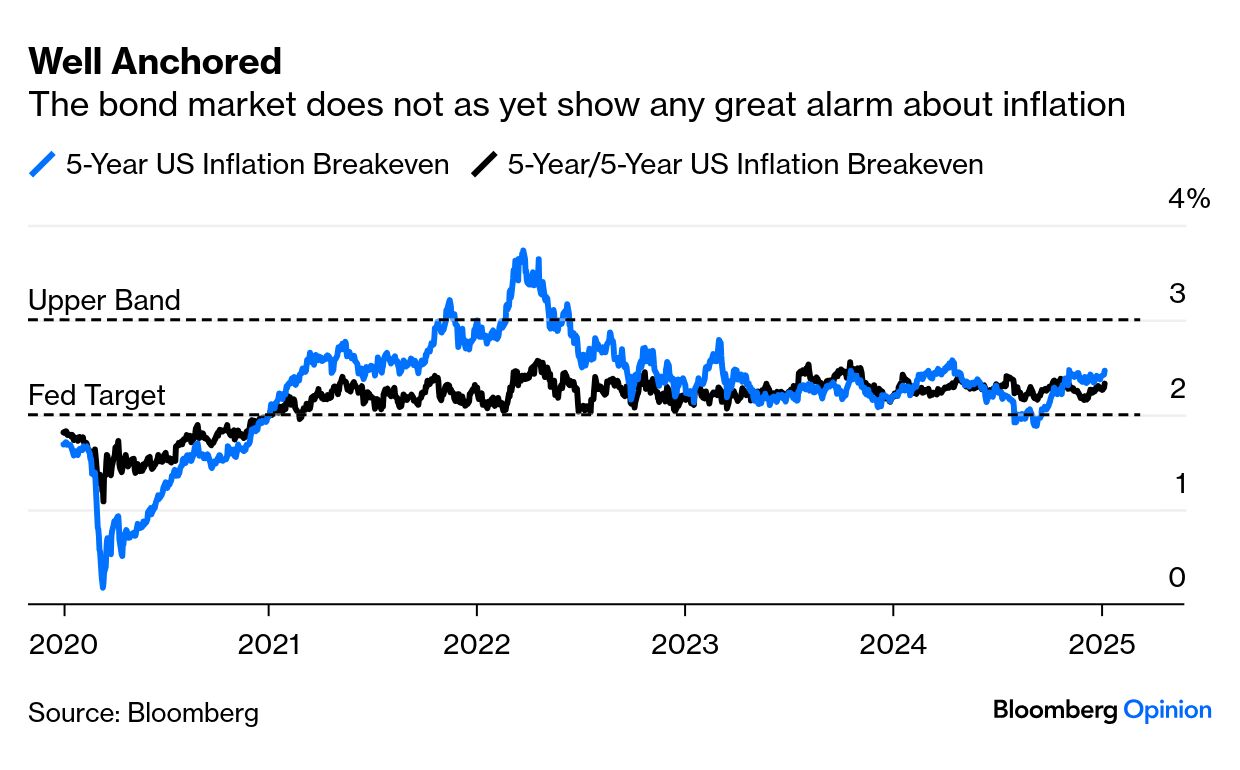

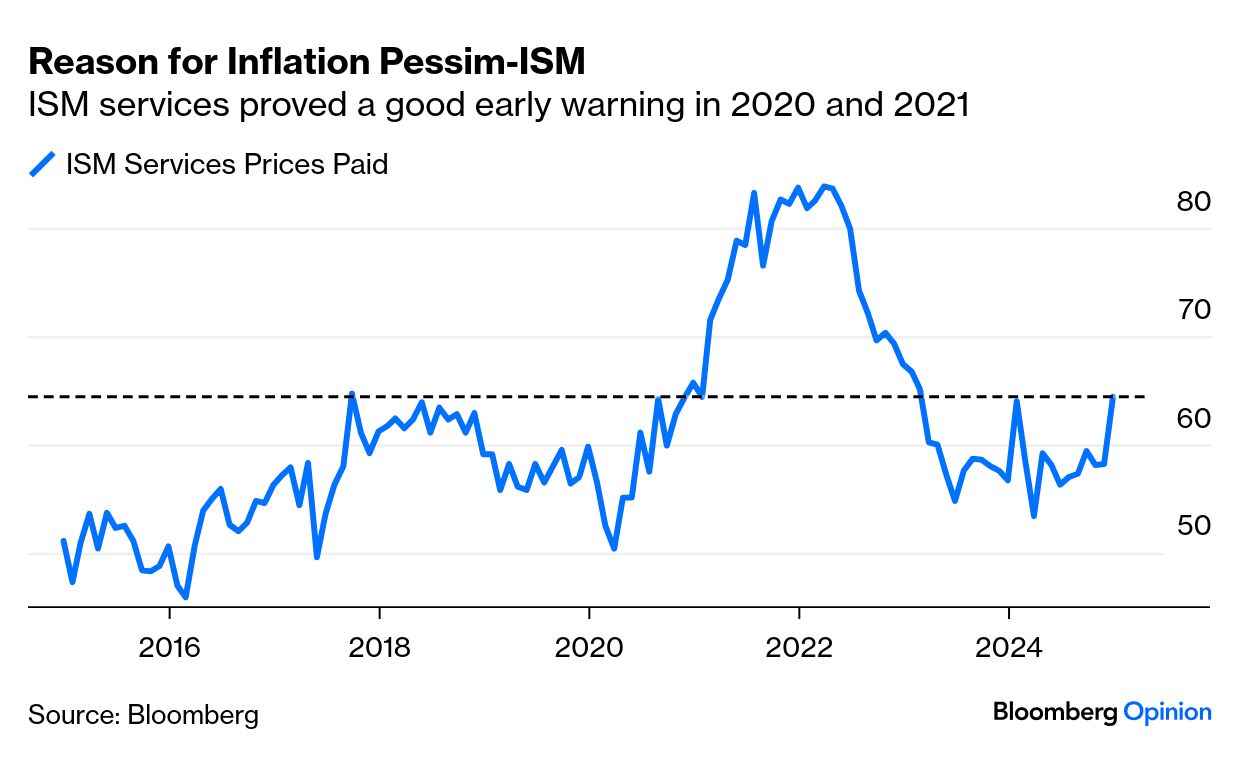

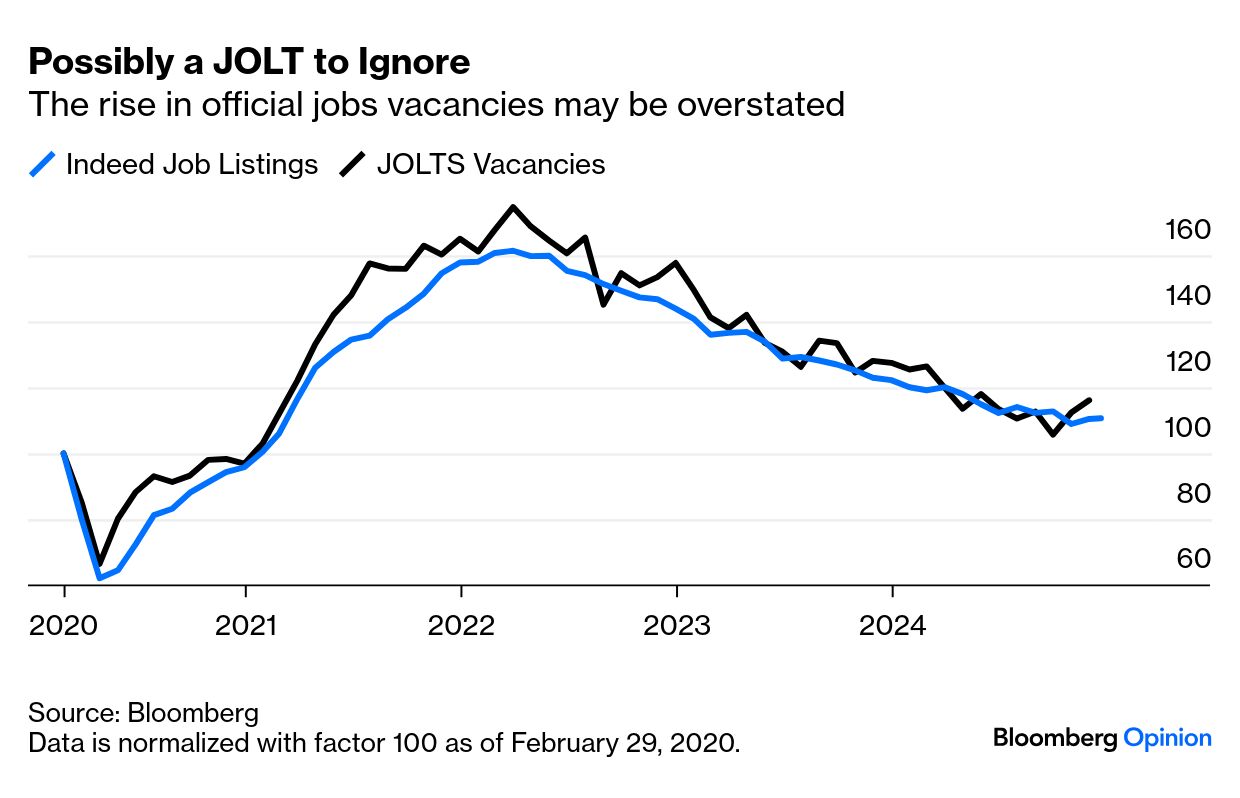

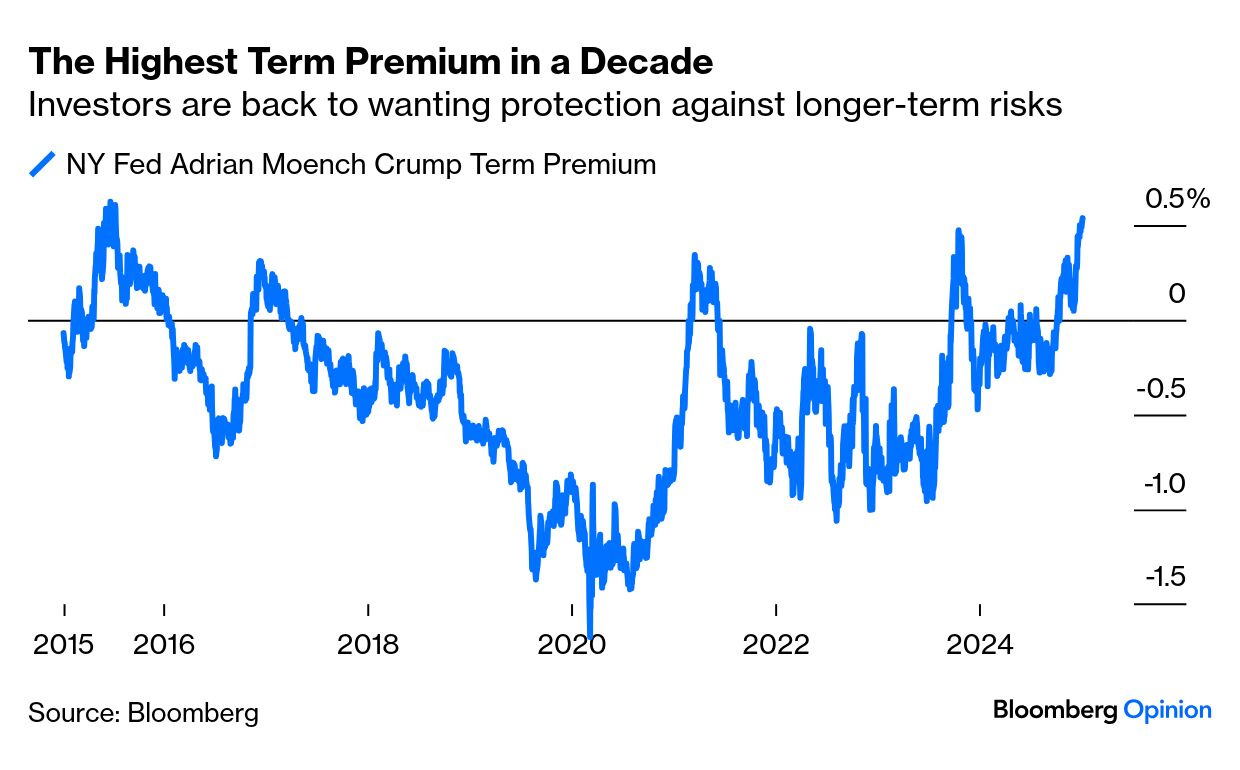

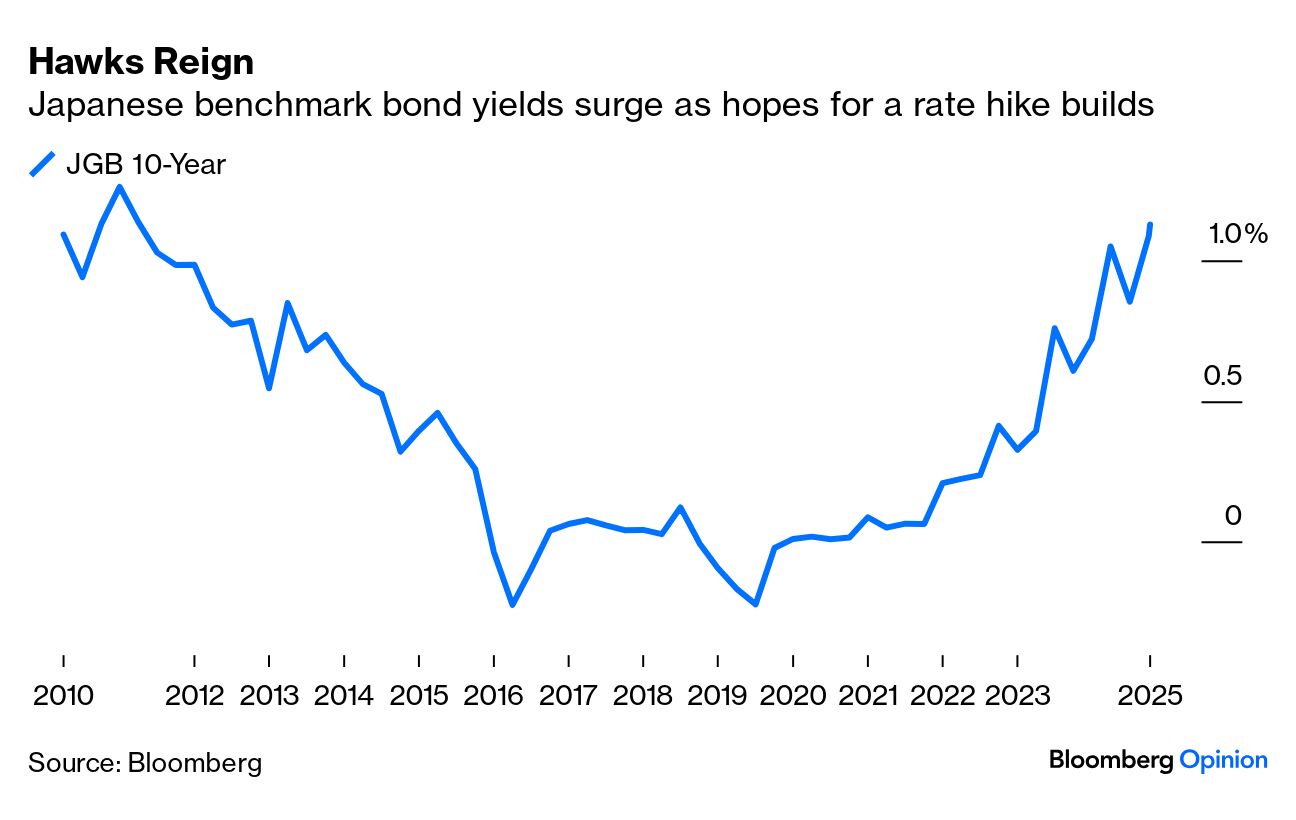

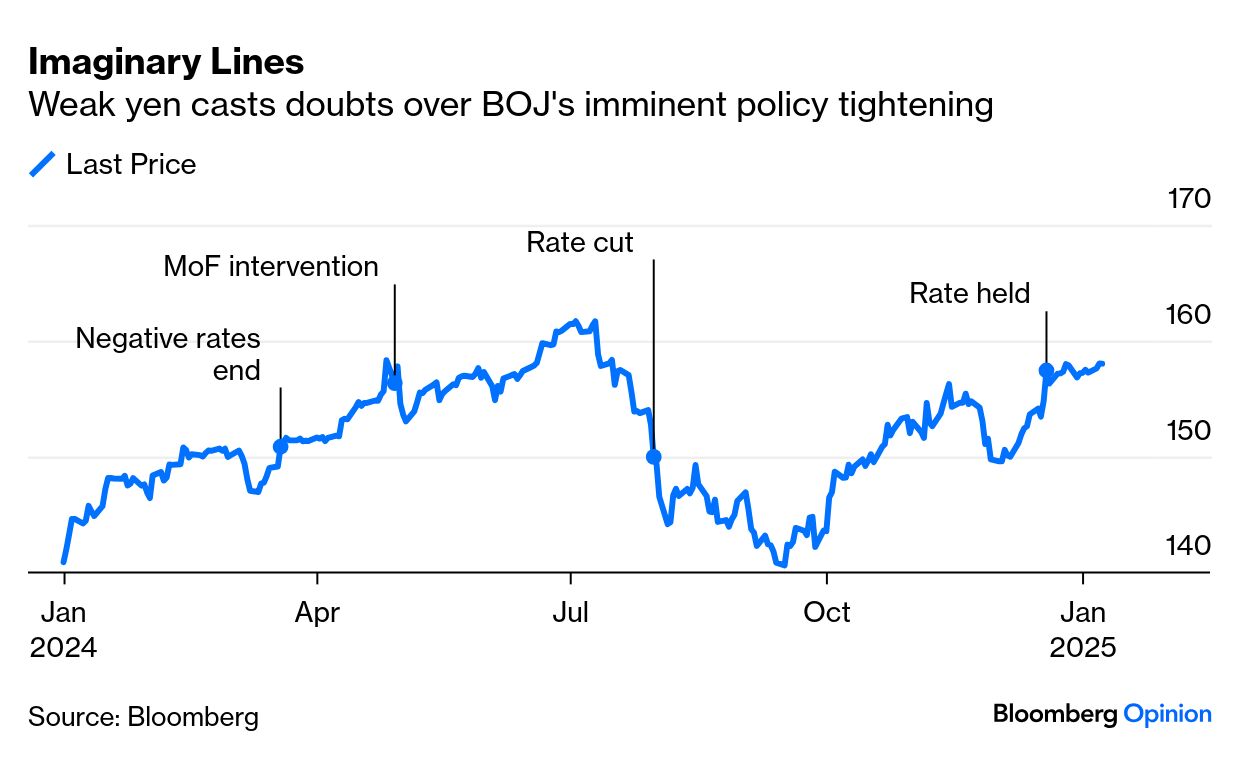

Score another win for the Ragin' Cajun. James Carville, Bill Clinton's political mastermind, is now 80 and has recently been in the news for a piece telling the Democrats that it's still "the economy, stupid." Donald Trump and the Republicans should note another of his most famous aphorisms — that he would love to come back as the bond market, because it can intimidate people. The Treasury market is looking intimidating again, and politicians should take notice, as should everyone else. This selloff is more complicated and ominous than some. It's also not limited to the US. Bond markets in the bigger European economies are also testing a high made late in 2023. There was a belief that policy rate cuts, made by all the main central banks, would ensure that remained the peak. It's now coming into question: This is primarily a story about the long end — or in less jargony terms, the bonds with longer maturities, which depend on more than short-term central bank expectations. The yield curve (the gap between the yields on two-year and 10-year Treasuries) is its steepest in 30 months. After a lengthy period of inversion (when two-year yields were higher, implying a bearish prognosis for the economy further into the future), the curve has steepened quickly in the last weeks. It still isn't particularly steep by historic standards:  The natural inclination is to blame the Federal Reserve, and it's true that expectations have shifted mightily since September, when the Fed started its cutting campaign by making a "jumbo" cut of 50 basis points. The expectation then was that rates would drop well below 3% by the middle of this year. Now, it's viewed as a marginal call whether they even reach 4%. Fed funds futures no longer see it as a certainty that the central bank will cut even once in the next six months: All else equal, such a change in expectations should bring yields up. But it's a strange reaction after the Fed's attempt at "shock and awe" back in September. As Torsten Slok, Apollo Management's chief US economist, demonstrates below, it would have been an unusual reaction if the Fed had only cut by a regulation 25 basis points. Once a cutting cycle has started, longer bond yields just don't rebound like this: Fears of rising inflation, which eats away at the value of future income streams from the bonds, logically raises yields. Inflation expectations as gauged by the breakeven point between fixed and inflation-linked bond yields have ticked up of late, but in the bigger picture they remain remarkably stable. This shows the implicit expectations for the next five years, and for the five years after that (a measure the Fed cares about a lot). They suggest that the bond market is still confident that inflation is back in the bottle:  The latest data, with the last readings on unemployment and inflation for 2024 due on Friday and next Wednesday, do give reason for concern. The Institute of Supply Management's survey of the services sector showed a sharp increase in the proportion of managers complaining about rising prices paid. As inflation is currently centered almost entirely in services, that is a problem. Moreover, this measure in hindsight provided a great early warning in 2021 that inflationary pressure was brewing:  Meanwhile, there has been a surprisingly strong jump in the number of US vacancies recorded in the JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey). However, Samuel Tombs of Pantheon Macroeconomics points out that this number is noisy (as Richard Abbey noted yesterday), and that data on job openings from the Indeed web-based recruitment site suggest that vacancies are stabilizing. During this decade, the Indeed measure has provided a smoother ride while working as an excellent early warning for the JOLTS:  So if this isn't a straightforward recalibration of expectations for the Fed and inflation, why the rise in yields? It's best to look to the term premium, an infuriating concept that refers to the extra yield investors require to take the risk of lending long into the future, and with it the risks that interest rates will change over that time. Colleagues Mike Mackenzie and Liz Capo McCormick have a nice explainer here. The point of the concept is to explain any rises or falls in yields that can't be put down directly to the Fed. Interestingly, after a long period when the term premium was negative, it's now its highest in almost 10 years (according to the Adrian Moench Crump term premium maintained by the New York Fed that is the most widely followed measure):  Why is it rising? Some political risk is in there. A Republican clean sweep has raised the threat of fiscal irresponsibility; bond markets prefer gridlock. The policy uncertainty that surrounds the return of Trump will naturally prompt investors to demand a higher term premium. Beyond that, there are the forces of supply and demand. Companies have celebrated the new year with a splurge of new issuance, which naturally tends to raise the yields that all bonds must offer. The Treasury under Janet Yellen has raised far more of its debt through very short-term borrowing than usual. That has the effect of reducing the supply of longer bonds and, therefore, reducing their yield. The Trump nominee to succeed her, Scott Bessent, wants to shift back toward longer-term issuance, which will naturally increase supply and hence tend to drive up yields. Investors can see this coming. The most important issue may be the secular trend. For decades after Paul Volcker tamed inflation in the early 1980s, the 10-year yield trended downward in the most predictable and important pattern in global finance. Whenever the yield rose to threaten the pattern, a crisis — Black Monday, the Orange County derivative disaster, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the Global Financial Crisis — would erupt, and yields would drop. That is over. And while it's never wise to make too much of drawing lines on charts, this latest rebound in yields suggests that a new trend is taking shape, as I've indicated here:  Demographics can explain this, as can what appears to be a return to inflationary psychology and worries about whether the US fiscal situation is sustainable. The point for now is that the balance of forces is pushing yields upward. The downward trend was in many ways the governing force of international capital markets for more than three decades; it might make sense to get used to the notion that yields will tend to trend up, not down, for the foreseeable future, and change conduct accordingly.  | | | Amazingly, something very similar is happening in Japan. Last month, the Bank of Japan voted to keep its rate unchanged. It wasn't a surprise. What caught the market off guard was Governor Kazuo Ueda's commentary that markets should not necessarily expect a hike at this month's monetary policy meeting. Until that hawkish hold, yields on Japan's 10–year benchmark bond had been moving sideways, flirting with the peaks seen after the exit from the negative interest rates policy in the first quarter of last year. The BOJ's summary of its December meeting set the record straight — a hike in January was still on the table. And with that, markets returned to pricing in a hike, sending yields on the 10-year government bond, held at zero for many years under the policy of yield curve control, climbing to the highest level since 2011:  As reticent as Ueda has been on the timing of the next hike, his case isn't helped by rising Treasury yields, pressuring him to act to stem the yen's slide. In recent days, the currency has dipped below levels that necessitated the Finance Ministry to prop it up with almost $62 billion last year. In the absence of a similar intervention, Finance Minister Katsunobu Kato is sounding out authorities' readiness for "appropriate action" against excessive moves. At the time writing, the yen is above 158 to a dollar, the weakest it has been in the last six months: Ahead of the BOJ's Jan. 24 meeting, the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probability function puts odds of a hike at less than 50%. Perhaps the only reason the door is not entirely shut is that upcoming US data might yet make one essential. Clearly, the US cutting cycle is taking a breather, but additional numbers will help provide a fuller picture of inflation's trajectory and subsequent implications for monetary policy. This matters to everyone else, and Japan is no exception. We saw that play out Monday as JGBs opened cheaper across the curve following a selloff in Treasuries necessitated by hotter US ISM manufacturing data. Ueda's team hopes to parse an avalanche of US data prints, including inflation and jobs, in coming days — before they retire to their meeting. Regardless, the consensus in favor of skipping a hike this month is growing, with Barclays PLC joining Bank of America Corp. and Nomura Holdings Inc. in pushing its BOJ rate hike call to March from January. Viewing the rise in JGB yields through a political lens makes sense. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba's political woes deepened after his party lost the lower house majority in October. His coalition government needs to work through opposition parties to implement policy plans. Ahead of an election for the upper house expected in July, a recent poll conducted by Nikkei and TV Tokyo showed him with a net disapproval rating. The botched Nippon Steel Corp. takeover of US Steel Corp. doesn't provide any comfort. Is the political mess enough to explain the rise in yields? Not entirely, but it cannot be discounted, either. Long seen as the exception to every rule, Japan is growing ever more similar to all the other countries suffering similar political problems. France, Germany, South Korea and Canada are all seeing yields rise. —Richard Abbey As expected, plenty of you have suggestions for songs to play when you need a big cathartic noise. Try Quiet Riot's version of Cum on Feel the Noize, Hush by Deep Purple, Black Dog by Led Zeppelin (and I'd add In the Evening), Steppenwolf's Magic Carpet Ride, Radiohead's The National Anthem, Prince's Endorphinmachine, Jimi Hendrix's Foxy Lady, Begging You by Stone Roses, Even Flow by Pearl Jam, and Rebellion (Lies) or Month of May by Arcade Fire. For really good results, look these songs up separately on different tabs, and leave them playing as you start listening to the others. It's the kind of cacophony that drowns out noise about the US invading Panama, buying Greenland, annexing Canada and renaming the Gulf of Mexico to become the Gulf of America. Points of Return will of course be analyzing all these things as and when they happen. Any more nominations? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment