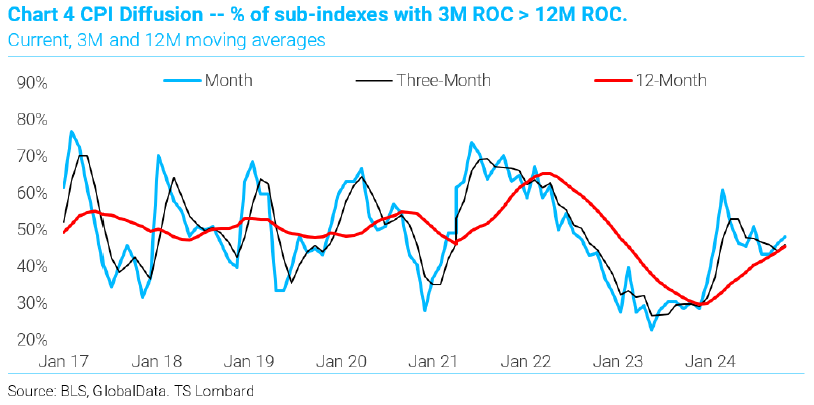

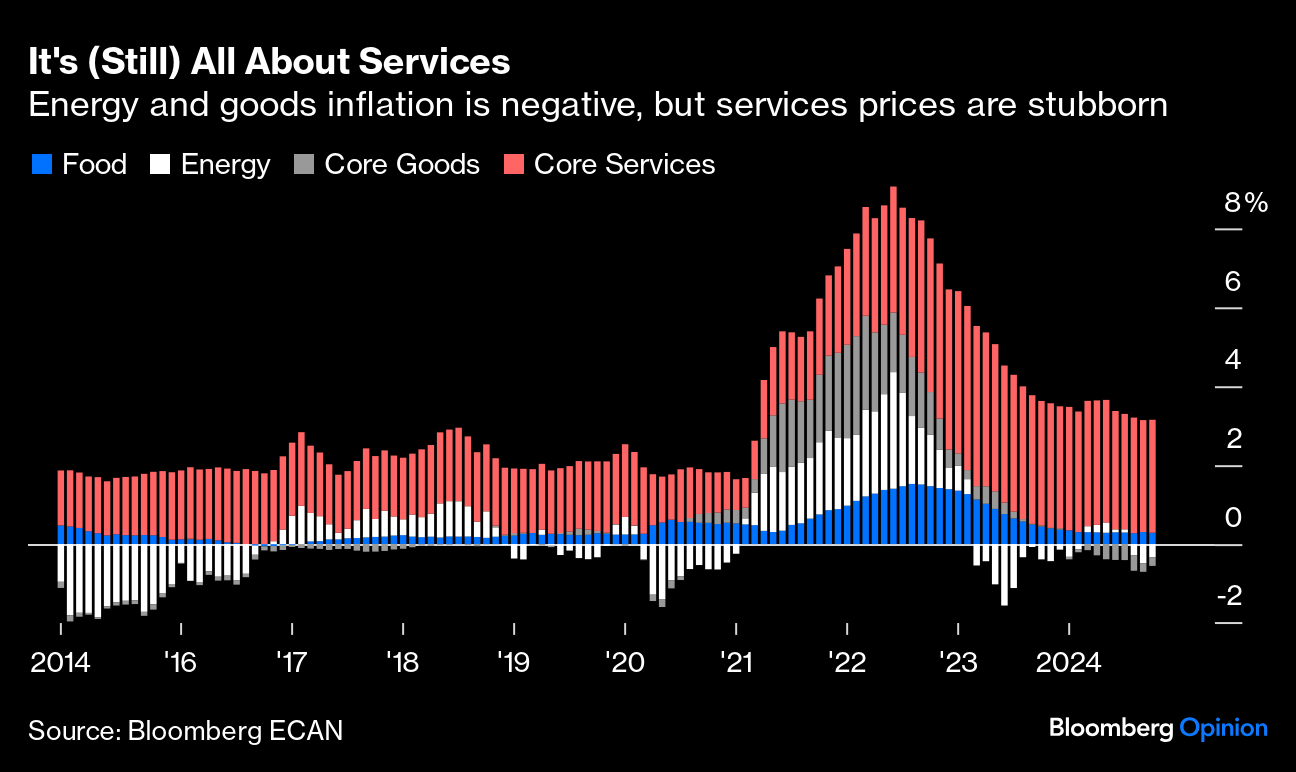

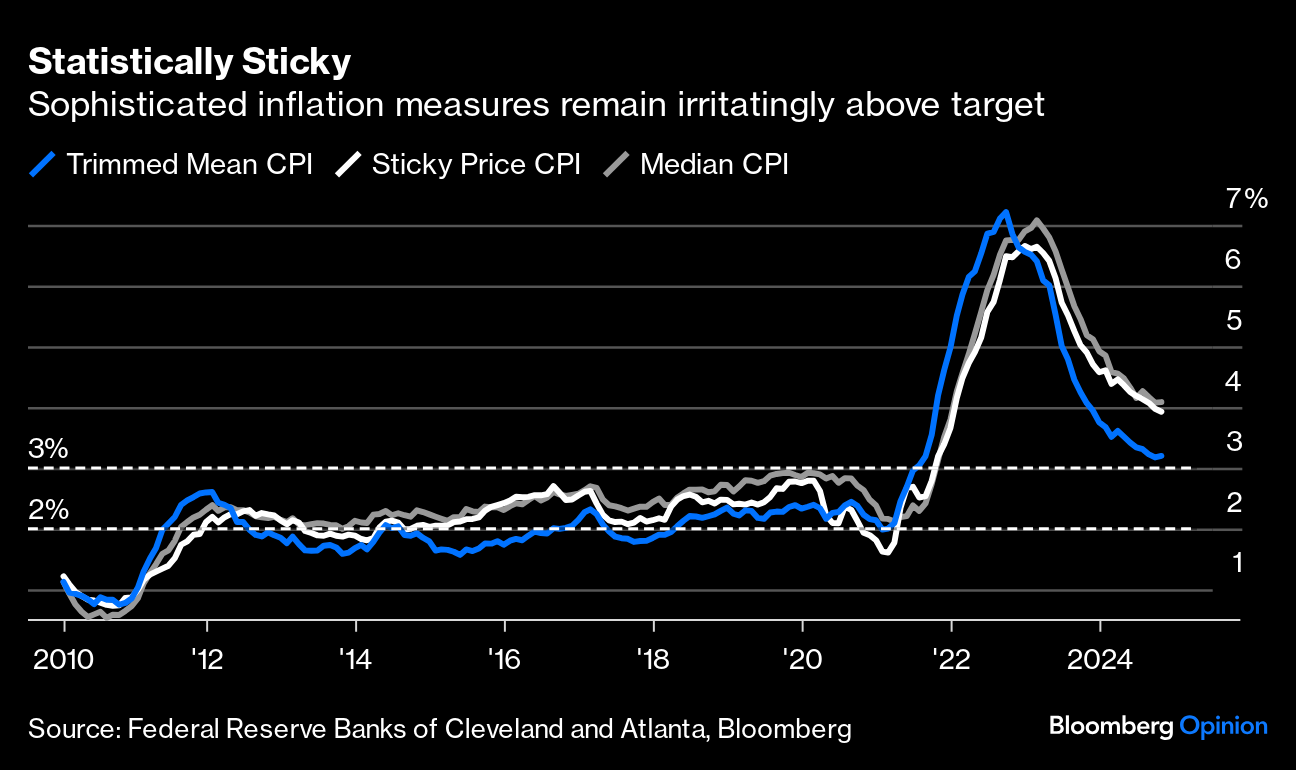

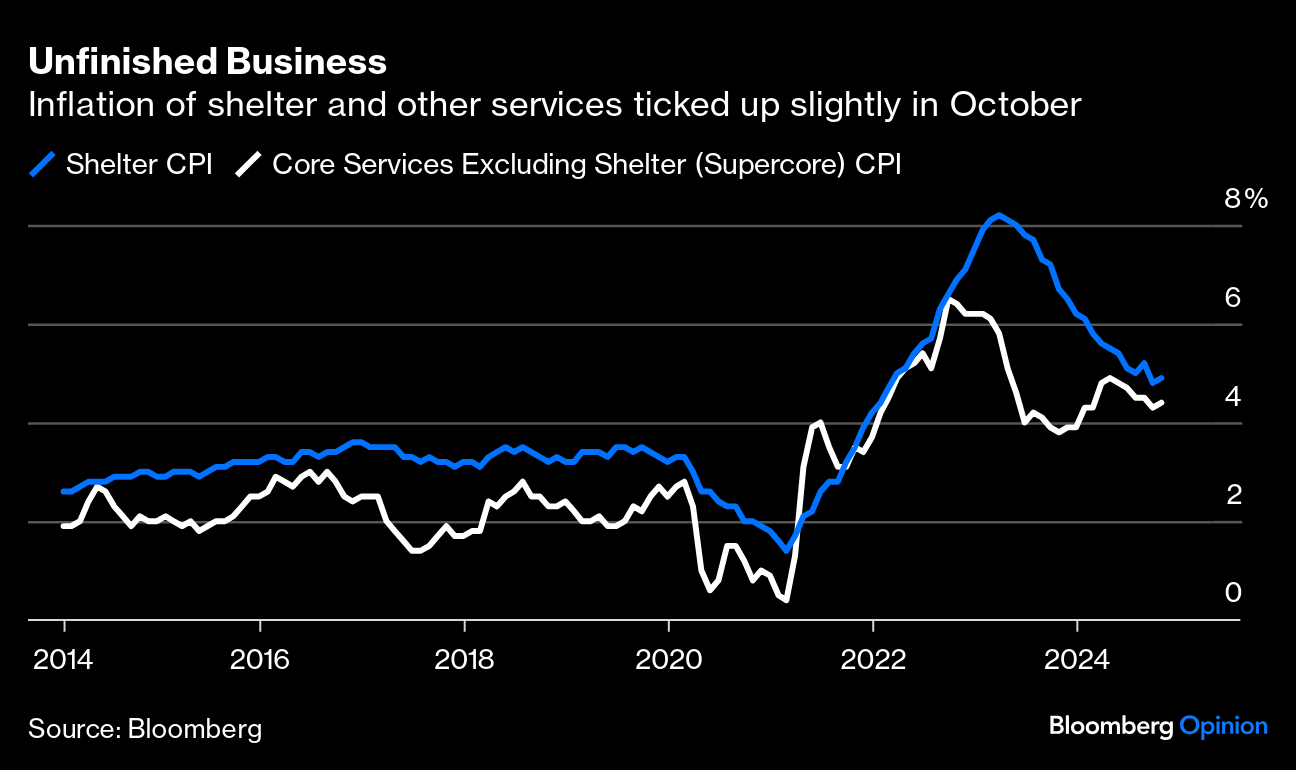

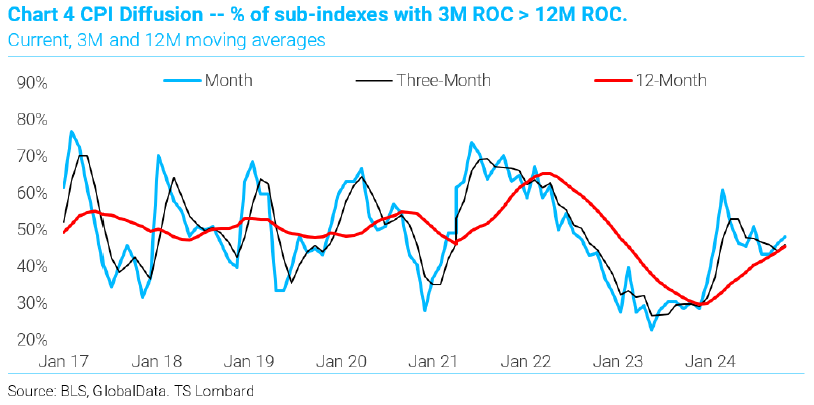

| Subtlety has been in short supply recently, particularly on the increasingly political subject of inflation. That's a pity because the problem in the US is now a finely balanced one, and policymakers will require great subtlety to deal with it. A fair amount is at stake. The latest US inflation data show that the issue is largely under control, but not that it can now be safely ignored. It's a pattern that is growing familiar, and clarity about the next step is still elusive. In essence, energy and goods inflation is now slightly negative, food prices aren't rising by much, but services — where salaries tend to be a particularly strong driver of prices — remain problematic. That leaves overall inflation above 3%, and still too high for comfort: The various specialist statistical measures drawn up by different teams of economists within the Fed confirm that inflation remains above 3% (the top of the Fed's targeted range) and is no longer clearly declining. This is true of the Cleveland Fed's median and trimmed mean (stripping out outliers and averaging the rest), as well as the Atlanta Fed's measure of sticky prices that are difficult to move: Moreover, the most problematic sectors have stopped falling. Both core services excluding shelter (the Fed's so-called supercore, which has been given much emphasis over the last couple of years) and shelter ticked up very slightly and remain above 4%: A diffusion index from TS Lombard's Steven Blitz illustrates in another way that disinflation (decline in the rate of price rises) is over. This chart shows the proportion of inflation components whose three-month rolling average is above their 12-month rolling average, an indicator of how many are trending upward. The figure now stands at 50% , which is unremarkable, but it's doubled since the beginning of the year. That's hard to square with any notion that progress is still being made toward target:  Taken together, the data probably don't justify another rate cut next month. However, the Fed has a dual mandate. The latest employment figures showed weakness, and so on balance the path of least resistance is to cut again, but only by 25 basis points. Further, there's a general expectation in the market that another cut is coming, and it might be dangerous to disappoint those hopes when the post-election markets are already volatile. Market reactions on Wednesday were muted in the knowledge that the Federal Open Market Committee will have fresh monthly reports on both inflation and unemployment to look at before they next meet. In that context, the October CPI needed to be a significant surprise in either direction to move the expected path of rates, and it wasn't. Carl Weinberg, chief US economist at High Frequency Economics, said: Our outlook for the Dec. 18 FOMC meeting is that a rate cut is likely but not assured. Today's CPI data do not affect that outlook. Fed Chair Powell said he was confident that progress toward the inflation target would persist. So inflation metrics still above target in this report are neither a surprise nor a threat to future rate cuts.

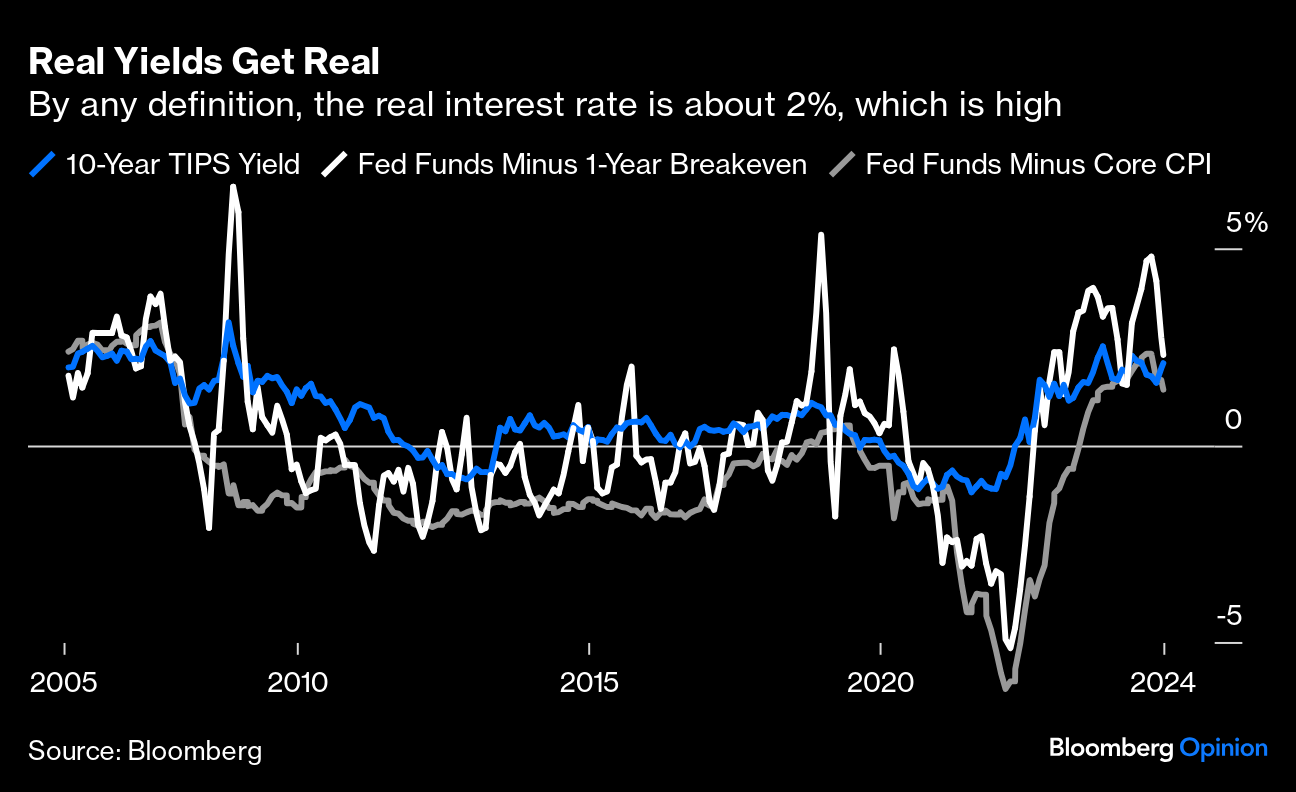

The Fed needs to continue its dialogue with the market, which has loosened financial conditions in the last week by bidding up stocks, while tightening them by raising bond yields. There are any number of ways to measure exactly how tight conditions are, and the current bout of speculative exuberance makes it hard to believe that they're very restrictive. But the Fed might take notice that the 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities yield, widely regarded as the best pure measure of real long-term interest rates, is settling above 2% again. If that doesn't sound like much, be aware that it stayed below 2% for 14 years until 2023. Conditions are meaningfully tighter than many currently working in finance have ever known. Definitional issues now grow more complicated, as Jerome Powell argued last year that the real rate should be defined as the fed funds rate minus the one-year inflation breakeven. This produces a much more volatile figure, and at the time it was considerably higher than the TIPS yield, so it was seen as the beginning of an argument that the Fed could afford to cut. Another popular real rate just subtracts core CPI from the fed funds rate. Those three measures are illustrated below. Adding the extra definitions shows 1) that it really was mad to leave rates so low for so long after the pandemic, and 2) that we can now agree that the real rate is a high but not extreme 2% (ish): Then there's the possibility of big changes in macroeconomic policy once Donald Trump takes office. If selections for his economic team create anything like the uproar that the nomination of super-loyalist Representative Matt Gaetz for attorney general has done, markets will get very interesting. Whoever gets the job will grasp that the new administration has a mandate both to pursue aggressive trade policy and to put a lid on inflation, and that the two could come into conflict. They, and the market, will have to strike a balance. Until we know the Trump team, it seems a fair bet that the Fed cuts next month (an 86% chance, according to fed funds futures), but then stops to await developments, with only a 16% chance of another cut in January. Blitz puts the case this way: In sum, with 4.1% unemployment, renewed real consumer spending power, and ongoing Federal spending, there is little reason to expect inflation to drift lower. There are one-offs in any month — auto insurance, used cars — but inflation is stabilizing at a level that reflects general macro conditions. One more cut coming from the Fed, call it unemployment insurance, then watch and wait to see what Trump's planned disruptions deliver.

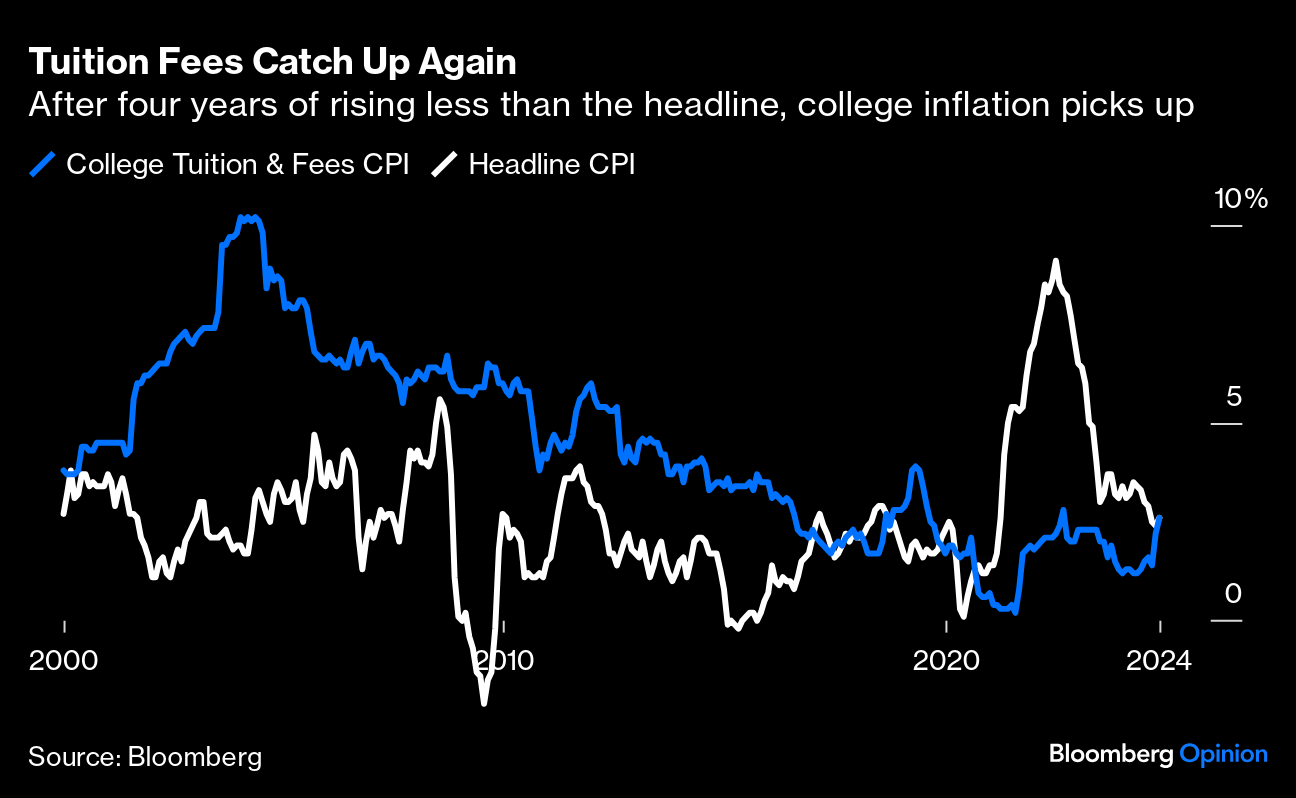

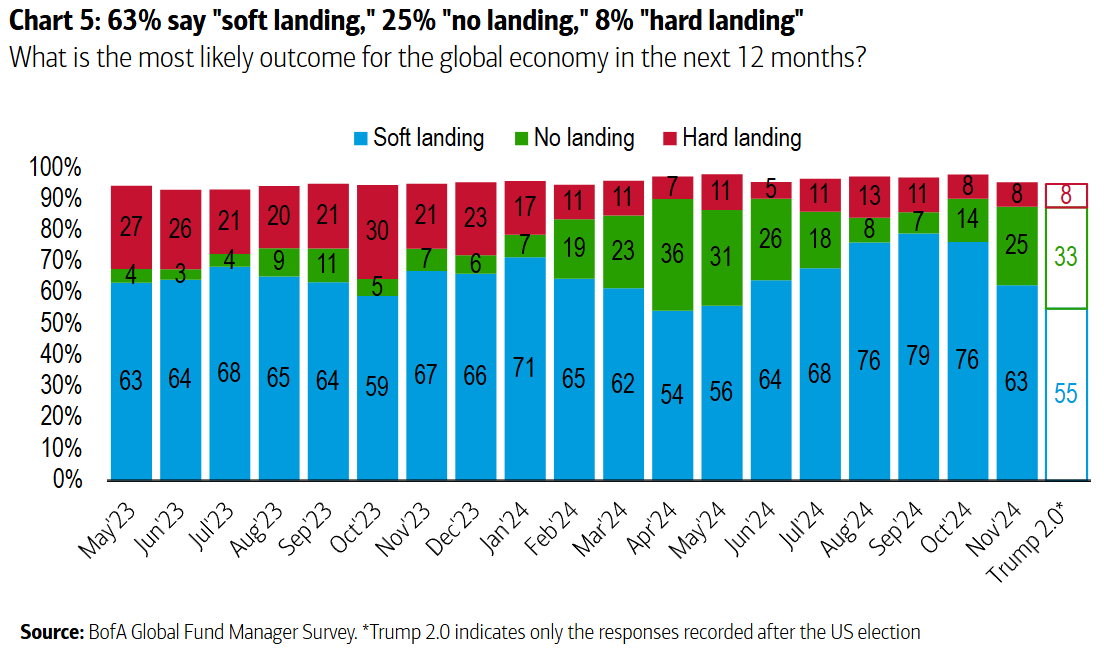

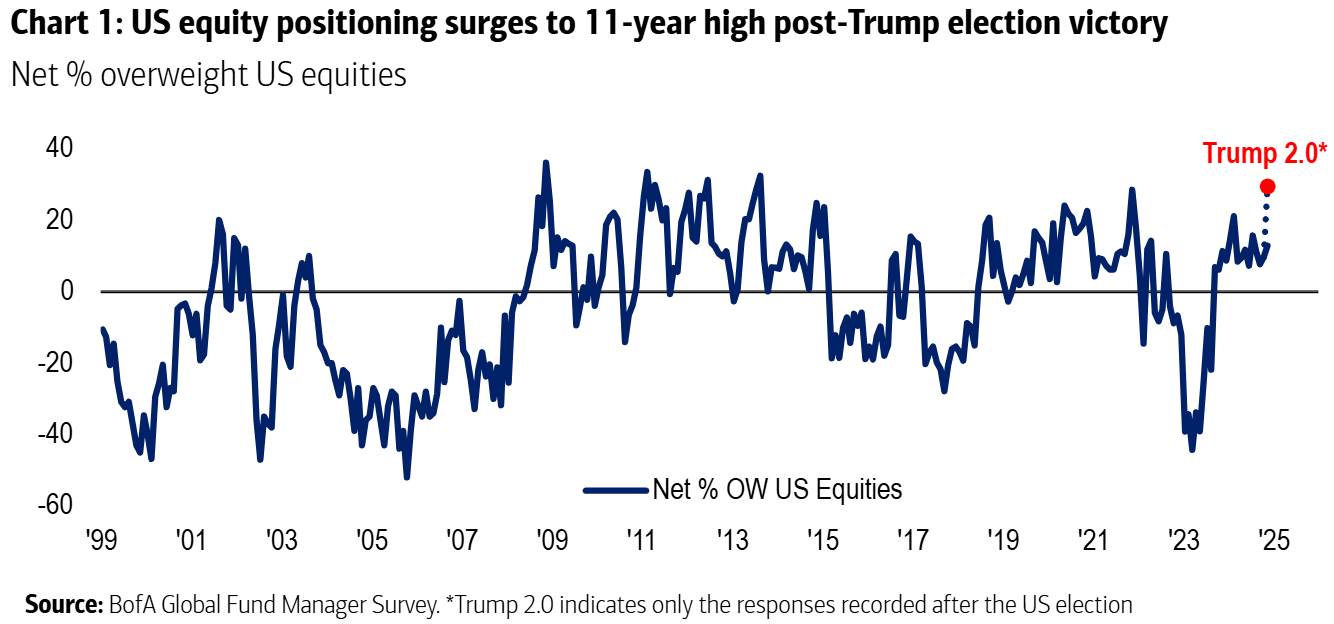

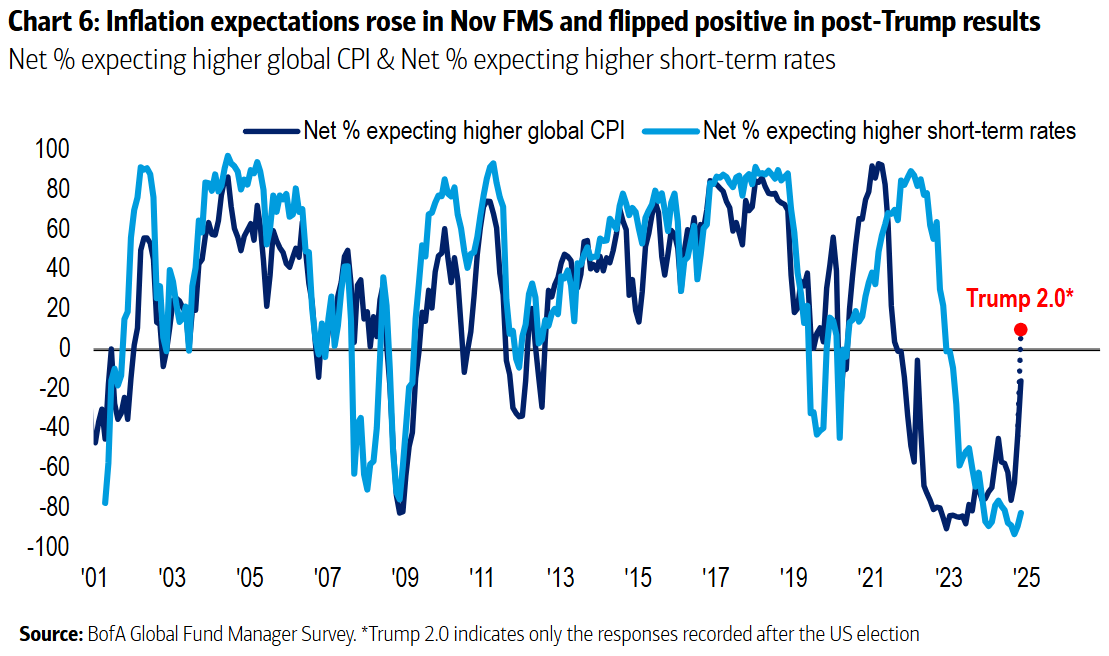

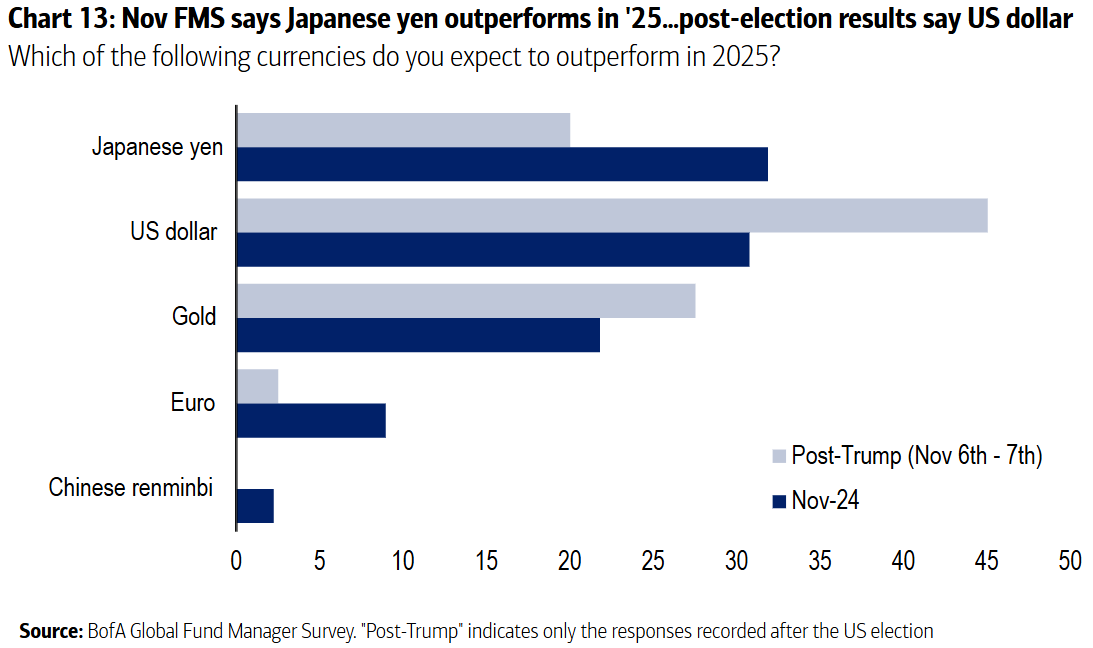

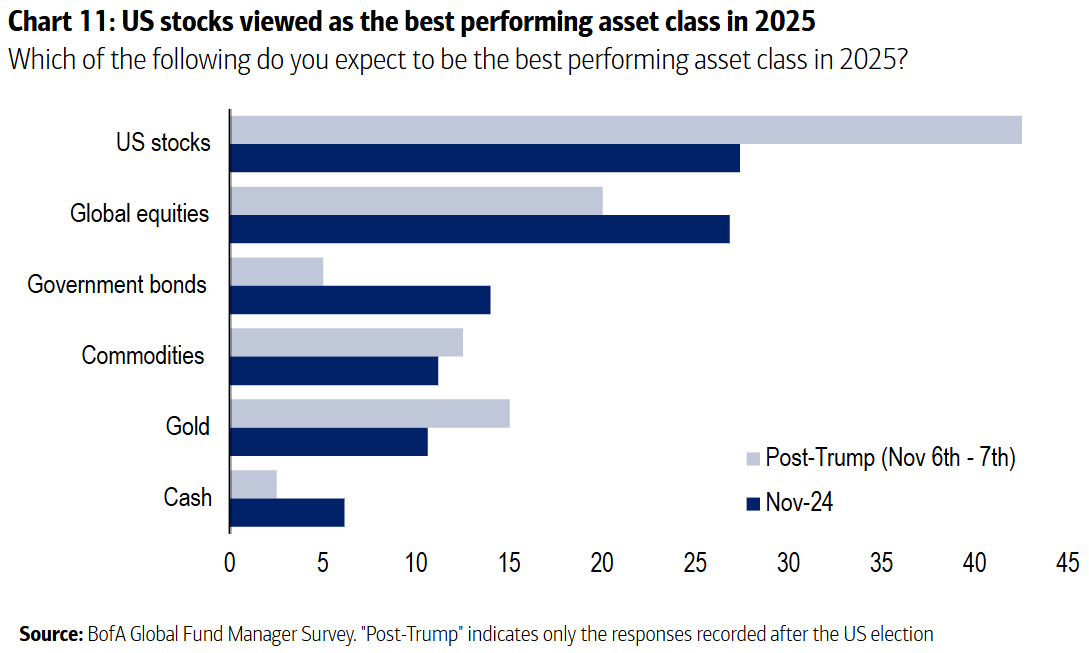

And one final note, which isn't great for political harmony. When it comes to the biggest item in my own household's budget, it looks like the tide may have turned back toward rising college tuition fees. They increased far faster than general inflation for the first two decades of this century, as colleges steadily made themselves unaffordable, but the pandemic appeared to have broken something. Universities barely raised prices at all as they tried to adapt to a new world and prove they were value for money. This was the first month since the pandemic when tuition inflation was as high as headline CPI again: Colleges need to be careful about this. (He wrote, trying to sound threatening.) Who has been making the Trump trades, and how much do they think last week's election has changed things? Obviously, there's some testosterone-assisted excitement buoying the most speculative trades such as Bitcoin, but the gains have been much broader than retail investors could have delivered on their own. The latest edition of Bank of America Corp.'s monthly survey of global fund managers suggests that the world's biggest allocators see the election as a turning point. BofA had done most of the survey work before election night, but about 20% of responses came in after the results were known. There is always the chance of noise, but breaking down the differences among the managers who could give their answers with the uncertainty lifted is very intriguing. Even before the vote, managers were rating a "no landing" — in which there is no significant economic slowdown and rates have to rise again — as a 25% shot. After the election, that rose to 33%: With overheating the greatest risk, it's not surprising that fund managers moved to put a much bigger weighting into equities. After the election, the percentage of respondents who said they were overweight in equities suddenly rose to an 11-year high. Coming from a survey of professionals, this is startling bullishness: The biggest downside of Trump 2.0 is that the risk of inflation is perceived to increase. On this issue, the election drove an even greater swing in expectations. After a period of overwhelming confidence in a decline, a small majority now thinks that global inflation will rise in 2025: That is the pressure that the Fed and the Trump administration will have to gauge over the months ahead. The other clear and dramatic shift in expectations was geographic. Prior to the election, it was popular to bet that the yen would outperform next year. People weren't so positive about the dollar. That turned around on Nov. 6. The dollar is now favored to overperform, investors are more bullish about gold, and optimism about the euro and the Chinese yuan evaporated: There was a similar turnabout when it came to stocks. Most managers had thought that global stocks should beat the US next year, a reasonable bet given the current gap in valuations. That reversed after the results came in, while the contingent of bond bulls dwindled: Does this make sense? Tariff barriers on the scale that Trump discussed on the campaign trail would be a really serious problem for more open economies. There is also the evidence of Trump 1.0. From his election in 2016 until the pandemic turned everything upside down in early 2020, the US stock market clobbered all others: The second Trump administration looks likely to have much more room for maneuver. Trump's first year in power last time was marked by what was dubbed a "synchronized global recovery," in which US stocks slightly lagged the rest of the world. This changed once the US tax cut had gone through and tariffs started to roll out. Nicholas Colas, founder of DataTrek International, says the following: You can rest assured that every global asset allocator is looking at this data right now as they ponder where to put equity market capital over the next four years, and its message is clear. A very large and economically powerful country with an explicitly nationalistic set of government policies will logically see better returns than the alternatives. That the history shows it generates better returns than literally any viable alternative only underscores this fact.

All of this is happening with US stocks starting more or less as expensive as they have ever been. That makes a big bet on America rather hazardous. But nobody is more conscious of overvaluation in the stock market than big fund managers, and they're making the America First bet anyway. Irresistible force, meet immoveable object. Not that I'm running on fumes or anything, but I'm going to suggest listening to the music Youtube started playing when I left my desk and forgot to turn the computer off. I'm not the greatest Coldplay fan, but the cunning algorithm obviously saw that I might find it a guilty pleasure. While I find their albums rather overproduced, they're much better live. Try this run-through of performances of the tracks from the X&Y album (not regarded as one of their best). It's good.

I'm in transit for the next few days, and Points of Return will be back in your inbox Tuesday. Have a great weekend everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Juan Pablo Spinetto: Trump's Contempt Is China's Gain in Latin America

- Conor Sen: Trump Inherits an Economy at a Tricky Time

- Aaron Brown: Trump May Be Good for Crypto — But Bad for Bitcoin

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment