| A few months ago, the Wall Street Journal ran an article that detailed how allies of former President Donald Trump were looking to curtail the Fed's independence. In the months that followed, Trump has since confirmed the essence of that article, saying in August, for example: "I think that in my case, I made a lot of money, I was very successful, and I think I have a better instinct than in many cases, people that would be on the Federal Reserve or the chairman."

With Trump in a tightly contested election for President, there would have been no better way for the Fed to put a target on its back than to front-load loosening of policy two months ahead of the election. Trump can argue that this is the Fed putting its thumb on the scale in favor of his opponent. And should he win the election, we should expect Trump to activate the mooted plans to restrict Fed independence. This part is particularly relevant about a small group working in secret: The group of Trump allies argues that he should be consulted on interest-rate decisions, and the draft document recommends subjecting Fed regulations to White House review and more forcefully using the Treasury Department as a check on the central bank. The group also contends that Trump, if he returns to the White House, would have the authority to oust Jerome Powell as Fed chair before his four-year term ends in 2026, the people familiar with the matter said, though Powell would likely remain on the Fed's board of governors.

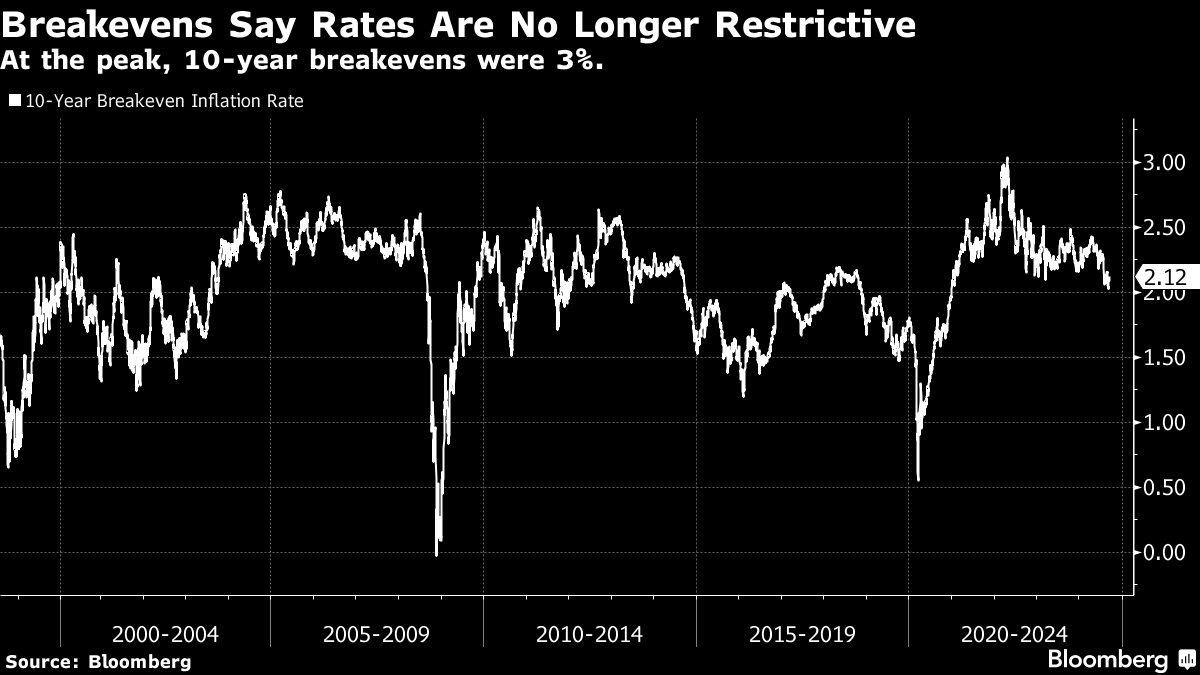

As this newsletter edition went to press, I hadn't seen any comments from the former president. But I expect they will come. In some ways, this is all water under the bridge. The Fed has made its decision and now we have to see what the consequences are. Both equity and bond markets took the move largely in stride given the furious pre-decision speculation. That's an indication investors think the Fed made the "right" decision. On that score, the dot plot of Fed projections tells you what comes next. Where in June, four members of the FOMC saw zero cuts this year, now even the biggest hawks — presumably Bowman and Bostic— favor 50 basis points of cuts. One Fed official even saw a case for 125 basis points of cutting this year alone. All told, the median, by just one vote, was for 100 basis points of cuts this year. The more relevant question goes to how the future years shape up. And there the Fed gets to the so-called neutral rate by the end of 2026, with 100 basis points more of cuts in 2025 and another 50 in 2026. And that projected neutral rate is now 2.9% versus the 2.8% we saw in June. All in all, not terribly dovish. But certainly not hawkish. The Fed decision is more of a signal to markets about what the Fed is willing to do or not do. Faced with arguably the most wide-open rate decision in nearly two decades, the Fed opted for a larger cut. The signal to markets: We've got your back. Now the market will push for another half-point cut. Even so, the longer-term outlook is much more colored by the path of rate cuts and the progression of the AI bubble. On AI, the arms race for dominance in Big Tech is as much about preserving existing positions as it is about the promise of new revenue streams. And so, there is some justification for spending tens of billions of dollars even if it's just keeping up with the mega-cap Joneses. But that spending has a sell-by date before investors clamor for evidence that the money has been well spent through a revenue boost or cost reduction. When this investment cycle ends, we need to see specific use cases for AI that mean incremental spend and productivity gains or AI spend will drop off a cliff. And the economy will suffer as a result. As for the Fed, it does have scope to cut more here given how high US base rates are relative to inflation. But the market has done most of the Fed's job anyway by front-running the cuts and bringing down the breakeven inflation rate implied by the difference in 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities and nominal Treasuries. In April 2022, the breakeven inflation rate was as high as 3%, well above the long-term average. Now, we're near 2%, somewhat elevated but not outlandishly so. In the end, as long as the US economy sticks the soft landing — and so far, it is doing just that — stocks can go higher. Bonds, on the other hand, have front-run the Fed too much and have little upside for the near-term. All of this will change when the AI shakeout happens. But, even though I think this is coming in 2025, just like with the entire US economy, resilience in this investment cycle could go on much longer than we think. There has to be a downside risk! And there is. It has to do with the trajectory we're on. Credit spreads are remarkably tight, creating a lot of downside risk in corporate bonds. Moreover, the S&P 500 is at the upper end of the trading range on the trendline from the lows reached during the Great Financial Crisis. And stocks have risen by some eightfold since then. By contrast, in the exact same time frame until 2007, when the GFC began, stocks had already gone through a roller coaster reflecting the Internet boom and bust, when stocks deviated from the longer-term trendline. The result: a fivefold increase in stocks — still robust, but arguably a better base from which to build gains. In the end, the market got what it wanted. That's great for the near term. At some point, though, this market needs a breather. |

No comments:

Post a Comment