Is it all going to work out?

In January 2011, Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and Fed Chair Ben Bernanke finalized a plan to keep the government out of default with just hours to spare.

A grab bag of technicalities conserved enough cash to allow the government to pay its bills without issuing the new debt that would put the government over its self-imposed ceiling.

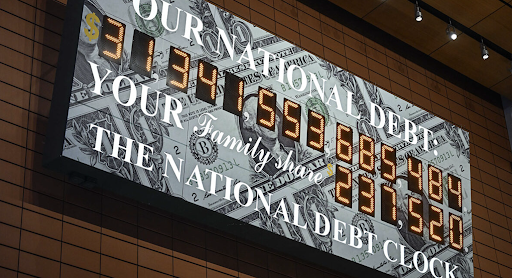

That was the birth of the "extraordinary measures" that have since become ordinary — so ordinary that you (like me) may have not even noticed that we again hit the debt ceiling way back on January 19.

That notable event didn't get much notice because in 2011, Geithner and Bernanke bought enough time for Congress to reach a deal on the debt ceiling, and now we assume that's how it works: Whatever has to happen ultimately will happen.

And most of the time, it does.

But assuming that everything will work out may remove the sense of urgency required for everything to work out.

Recall that in the 2008 financial crisis (the one that inspired Bitcoin!), the TARP legislation that rescued the global financial system only passed on a second try: Congress needed to see the S&P 500 fall 8.8% in response to the first failed try before they could bring themselves to do what very obviously needed to be done.

The 2022 banking crisis has not yet risen to a level that would require congressional legislation — regulators don't have to ask permission to seize banks and absorb billions of losses, as they did this morning with First Republic.

But a debt ceiling crisis can only be resolved by congressional legislation and, so far, Congress has not shown much interest in working on it.

That's largely because we've become so comfortable with Geithner and Bernanke's 'extraordinary measures' — and the Fed's willingness to fix every financial crisis — that being four months past the debt ceiling has failed to instill any sense of urgency in our political representatives.

But that may be about to change.

D-Day is coming

As close as we cut it in 2011, the market seems to think we're cutting it even closer this time: The spread between 1- and 3-month Treasury yields hit an all-time high last week, reflecting growing fears that holders of the latter may not receive their interest payments on time.

And the cost of insuring those Treasurys (with credit default swaps) has already exceeded the highs of previous debt ceiling debates.

That's because weaker-than-expected tax receipts are pulling Default Day forward: We thought the Treasury's extraordinary measures would find enough change in between the sofa cushions to get us through to, say, mid-August.

But it's now looking more like June. Possibly early June.

Whenever it is, it's not clear what happens when we get there: Previously, legislation to raise the debt ceiling has always been passed before the Treasury's extraordinary measures ran out.

But early June, if it comes to that, is too soon for any kind of legislation to be agreed.

Even this realization has failed to instill much of a sense of urgency in either Congress or markets: We seem to be trusting that because it's always worked out before, it'll work out this time, too.

And maybe it will: When the Treasury's extraordinary measures run dry, the Fed could get creative.

The minutes from the FOMC meeting of October 16, 2013, include a discussion of what measures the Fed might take if the Treasury were to run out of cash before legislation is passed to raise the debt ceiling.

None of the options are as dramatic as the much-discussed trillion-dollar coin — the Fed would not be looking for a silver bullet, they'd just be trying to buy more time for Congress to finally act.

They'd be buying that time reluctantly: The most effective options were deemed "loathsome" by Powell.

But loathsome might be what gets us to urgency.

The Fed would be taking unprecedented actions, and it's not clear they would work. Markets would price in some increasingly large probability that they won't — and that could create enough pressure on both political parties to force a compromise.

That's how Moody's sees it playing out, according to a recent note: They see the White House eventually accepting Republican-proposed spending cuts that would reduce 2023 GDP by a modest 0.65% … which, given the Fed's ongoing struggle with inflation, might even be a good thing.

But the road from here to there is perilous: Powell's loathsome measures will have to thread the needle of keeping the Treasury out of default while also spurring Congress to action.

Because, unlike the banking crisis, the debt ceiling crisis will come down to politics.

So politics is what we'll have to start paying attention to.

And paying attention to the seemingly intractable politics of raising the debt ceiling?

It's enough to make a guy want to buy bitcoin.

No comments:

Post a Comment