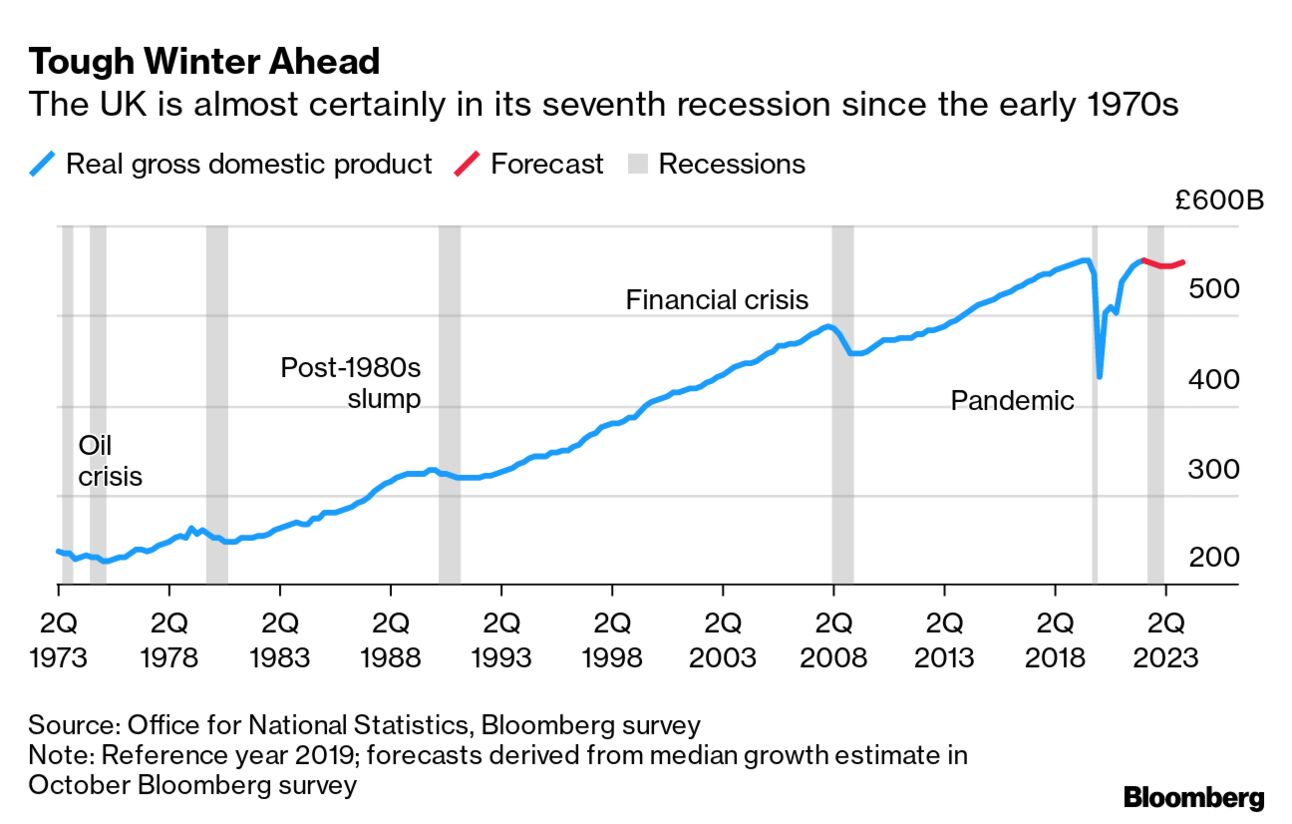

| Hello. Today we look at how tight labor markets are proving a challenge for central banks, this week's big central bank meetings and what history says about the future of interest-rate hikes. One of the biggest uncertainties facing policy makers right now is when will strong jobs markets crack under the weight of surging interest rates. It's a question that's dividing opinion among analysts. Some are warning that unemployment remains a lagging indicator and big job cuts will eventually start to surface. Others are pointing to the vanished millions, those workers who quit during the pandemic leaving a structural shortage of labor around the world. Regardless, strong employment figures in developed economies is one of the reasons central banks have been able to push through the most aggressive rate hiking cycle in decades. Analysis from the OECD, for example, shows unemployment in its 38 member nations reached 4.9% in August. The rate was below or equal to the pre-pandemic level in 80% of the countries. Should that data begin to turn, it would inevitably make it much tougher politically to justify higher borrowing costs. It would also erode the prospects for pulling off a soft landing. History shows that gliding their economies to a soft landing while raising rates is not easily done. In 1994-1995, under then-Chair Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve doubled interest rates to 6% and succeeded in slowing economic growth without killing it off or fueling unemployment. But during periods of high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s, Fed tightening led to unemployment rates surging to 9% in 1975 and 10.8% in 1982. That's the big unknown as we head towards 2023. — Enda Curran The Federal Reserve and the Bank of England may both unleash 75 basis-point interest-rate hikes in the coming days in a show of aggression toward inflation, even in the face of mounting recession risks. The transatlantic double act illustrates the trade-off confronting central banks as evidence of an impending global economic contraction becomes harder to ignore, even as inflation lingers. For the Fed, the fourth such out-sized move on Wednesday will bring it to a crossroads. The damage to growth inflicted by policy tightening is no longer being masked by the buoyancy of the post-pandemic economy, while its success in taming inflation has yet to materialize. The BOE's situation on Thursday is even less comfortable as it delivers what would be the biggest UK rate hike since 1989. Not only is the country probably already in a recession, but officials are also trying to reestablish the credibility of the UK's framework after former Prime Minister Liz Truss's unfunded fiscal plan led to a disastrous market crisis. Even sooner, Australia's central bank must decide Tuesday whether to return to outsized interest-rate hikes. The week then ends with the US payrolls report, which economists reckon will show a slowing in hiring. Here's our wrap of what's coming up in the global economy. The fifth annual New Economy Forum will be held in Singapore this November 14-17, convening public and private sector leaders with ambitious ideas, ample capital and the courage to act on the pressing issues facing the global economy. Learn more and get exclusive alerts to watch the livestream. - Lula wins | Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva won election as Brazil's president in a dramatic comeback for the left-wing politician who was languishing in a jail cell just three years ago on corruption charges.

- UK pressure | Rishi Sunak's first full week in power is set to be challenging especially as signs mount that higher interest rates are squeezing the economy and he lacks a plan for growth.

- China weakens | China's factory and services activity contracted in October as tighter Covid curbs and an ongoing slump in the property market continue to pressure the world's second-largest economy.

- Stagflation threat | Euro-area inflation surged to a fresh all-time high, while the bloc's economy lost momentum — reinforcing fears that a recession is now all-but unavoidable as the European Central Bank continues to focus on fighting high prices.

- Food threat | Traders are bracing for a fresh spike in grain prices after Russia's exit from a deal allowing Ukraine crops to move from the Black Sea to the countries most in need of them roils markets anew.

- Kiwi advice | New Zealand Finance Minister Grant Robertson has sought advice on whether the central bank should be asked to achieve its inflation and employment targets within a more specific time-frame.

- Lipstick indicator | Persistently high inflation and gloomy economy forecasts haven't led to a boom in the purchase of cheaper cosmetics.

- Chip decline | Global chip sales contracted for the first time since early 2020, in a blow to South Korea's economy which is highly geared to the industry and struggling to adjust to weaker demand.

Bank of America estimates there have been almost 250 interest-rate hikes so far in 2022, which is equivalent to one for every trading day. So what next? Goldman Sachs economists led by Jan Hatzius have poured over 85 hiking and easing cycled from 1960 to 2019 across key economies. Here's what they found: - Hiking cycles in major economies lasted just over 15 months on average, with longer cycles in the US and shorter ones in the UK, Canada, and Australia. Hikes tended to average 200 basis points.

- Longer cycles didn't necessarily involve much larger increases in the main rate and 75% of hiking cycles featured a pause

- Central banks tend to stop hiking when year-over-year inflation is still relatively close to its peak without necessarily having fallen significantly

- Relatively large rate cuts tend to come fairly soon after the hiking ends

"This analysis supports our view that the hiking cycle may extend further into 2023. However, even if cycles extended deeper into next year, our findings also suggest that central banks are likely to slow the pace, such that the terminal rate does not increase too much."

Read more reactions on Twitter here |

No comments:

Post a Comment