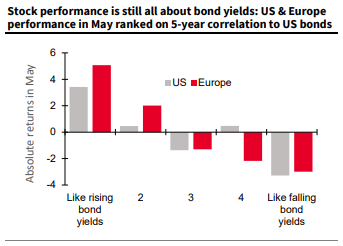

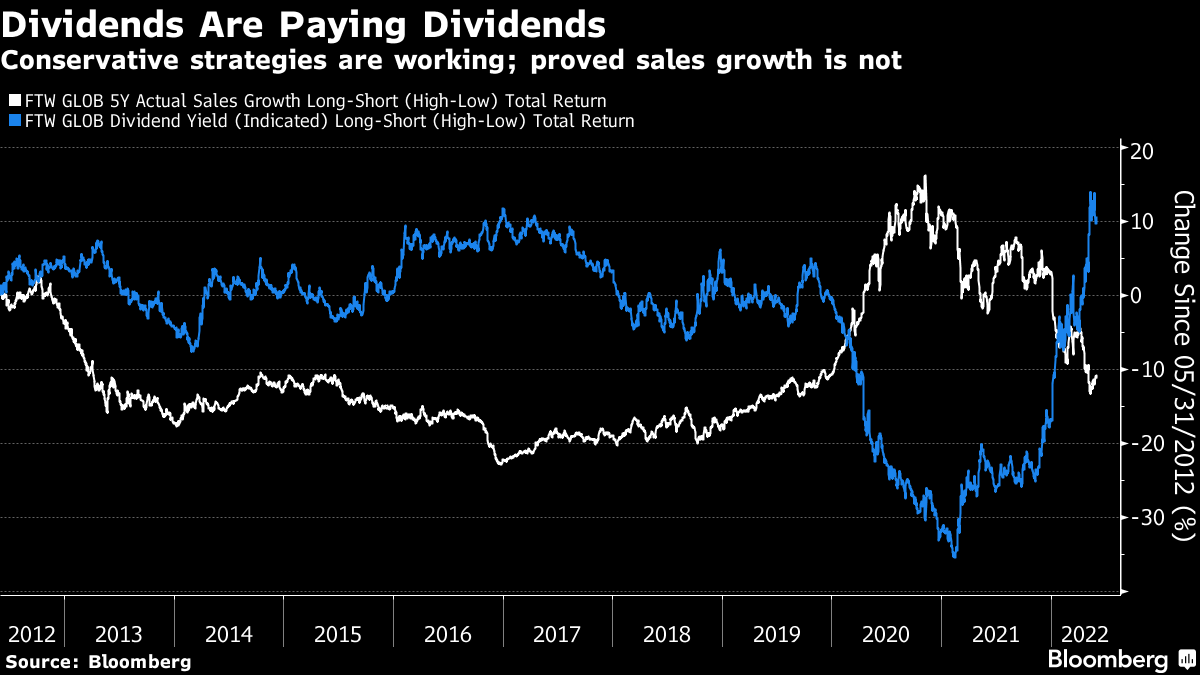

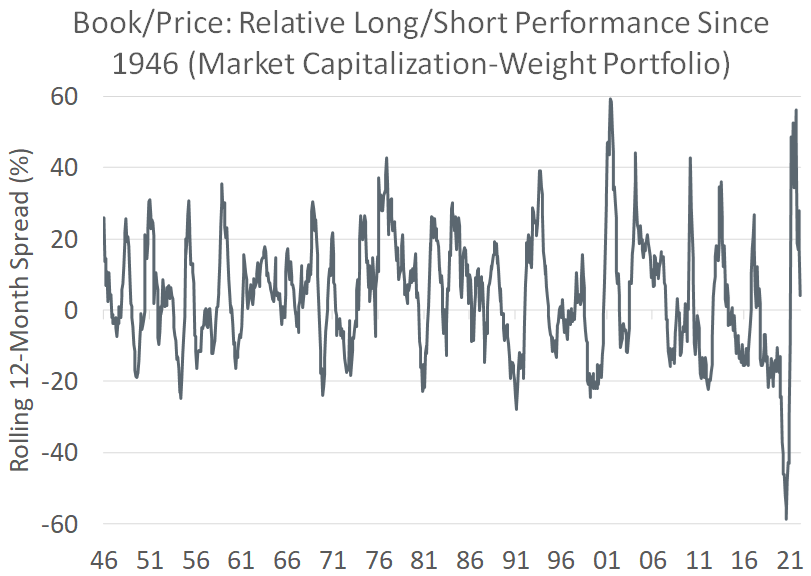

| Everything is inevitable once it's already happened. A few years from now, it will be so obvious where the world economy was heading in the summer of 2022. How could people at the time possibly have been in any doubt? In real time, however, doubt is not only widespread but necessary. And with divergent scenarios ahead of us, markets are priced for an outcome that nobody actually thinks will happen. As is more or less always true, nothing matters more than the 10-year Treasury yield, which sets the "risk-free" rate for transactions around the world. That yield is formed by innumerable transactions by people consciously or unconsciously expressing their view on the long-term direction of the economy. The final number represents a compromise between the views of buyers and sellers. And it ultimately represents a scenario that few believe can occur. The analogy is with the statistical concept of "expected value." That takes each possible outcome multiplied by its probability, and adds them together to find an expected outcome. For example, if you have to draw one of two cards, numbered 1 and 2, then the expected value of the card you draw is 1.5 ((0.5 *1) + (0.5*2)), even though there is zero chance that this number will show up. Similarly, there are two dominant narratives for the bond market at present. One is that inflation continues to mount, without bringing economic disaster in its wake, and so the Federal Reserve and other central banks have no choice but to keep hiking rates. The other is that the Fed swiftly realizes it has "broken something," growth slows sharply, and monetary policy goes into reverse. The former implies bond yields will need to rise significantly from here, while the latter implies that they must fall. As investors wrestle with the evidence, we are left with rates that are very unlikely to be suitable for the outcome that results. As this was the first day of the month, it brought the standard download of monthly data. Mostly, it was consistent with an economy still in decent health with persistent inflation, so bond yields rose again. But they remain distinctly too low if inflation is really going to be as bad as many now fear. Looking at the ISM supply manager data for US manufacturers, the headline index rose slightly — very much against expectations. Its measure of employment dipped below the 50 level that marks the border between expansion and recession, but only just. This measure spent a long time at lower levels than this during the post-crisis decade: Meanwhile, manufacturers' complaints about prices remain historically high. Usually, after a spike like this, prices have swiftly reverted to more normal levels, but not this time. This may be exacerbated by continuing backlogs, although the problem isn't as bad as it was a year ago: As for the job market, at the center of concerns that inflation is going to prove durable, it remains very tight, implying a strong negotiating position for labor. The JOLTS survey of job vacancies in the US fell slightly from month to month, but remains phenomenally high: More surprisingly perhaps, supply manager surveys for Europe also show continuing resilience, despite the drawn-out conflict in Ukraine. Italy is lagging, but the main economies of the region are converging around the level of 55. This isn't an economic boom, but it's far too high to justify the negative overnight rates currently on offer from the European Central Bank: How does this translate into markets? The two-year yield and the fed funds rate implied by the futures market for next February both saw a dramatic surge, or "tantrum," in the first three months of this year, and have since wobbled downward. The market currently expects a fed funds rate of just under 3% after the central bank's meeting early next year, while the two-year is a little lower. That implies tightening, and then rate cuts within two years. This is possible, but most would think rates should be much higher or much lower than that 24 months from now:  As for the 10-year yield, which has also retraced some of its advance in the last few weeks, it remains below 3%, after a sharp rise in response to the latest data. The turn down last month awakened hopes that the yield was now going into reverse — but that looks somewhat hopeful. Here is the famous downward trend going back four decades, with its 200-day moving average. The yield has never in all those decades been as far above the 200-day average as it is now.  This looks much more of an interruption to the long-term trend than perhaps the most similar incident, the "taper tantrum" of 2013, when a sharp rise in yields tailed off as the Fed retreated by tapering its asset purchases much more gently than had been expected. If the Fed is to retreat again, history suggests it will need to do so soon. Otherwise, it looks as though decades of a steadily declining cost of money might actually be over. It's hard to imagine the 10-year yield moving calmly in a horizontal line from here; the current price is a compromise between those who believe that a new inflationary era has begun, and those who expect the Fed to respond to gravity any day now. Stock markets had a difficult day after strong economic data, which helps show that high rates at this point are regarded as the chief concern. Looking at the first-quarter earnings season and the change it wrought in analysts' expectations for growth in profits and revenues over the full year, there is little or no evidence of concern about an economic slowdown. As this chart from FactSet demonstrates, expectations for 2022 earnings are slightly higher now than they were when the first quarter ended: This is despite nerves in the bond market in that period. Meanwhile revenues, more directly tied to the state of the economy than profits, are also projected for healthy growth of 10.2% for the year as a whole. That's more than was expected at the end of March: But what's fascinating is that even earnings expectations are almost a function of the overarching debate over the course of inflation, rates and the Federal Reserve. Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist of Societe Generale SA, offers this summary, dividing changes in earnings forecasts over the last month according to how companies tend to be correlated to bond yields: The companies with the most positive upgrades were the ones that would benefit most from higher yields, while those written down were the ones most helped by lower yields. So brokers are implicitly still placing their bets on economic growth and a continuing rise in rates. Exactly the same trend shows up in share performance for the month of May. The best-performing stocks were the ones that benefited from rising rates, and this was true on both sides of the Atlantic:  This ties into a nightmarishly difficult environment for stockpickers to navigate. For much of the post-global financial crisis decade, stocks with proven long-term sales growth tended to fare poorly, while high dividend payers did well. With rates on bonds so low, the prospect of a yield from equities grew that much more positive. During the pandemic this switched dramatically — people filled their boots with growth, and showed little or no appetite for companies with high dividend yields. Since the beginning of last year, that has reversed again. The following chart shows the results of going long the fifth of stocks that show up best on these factors while going short the bottom fifth, as calculated by Bloomberg's Factors to Watch function:  "The current regime, risk-off coupled with policy tightening, favors low risk and short-duration, dividend-focused strategies," says Lapthorne of SocGen. "For those wanting to jump back into Growth, you must ask how likely is it central banks will be easing anytime soon?" Where does that leave value investors? By many measures, it looks as though the value rally might already have run too far. However, Alexander Atanasiu, quantitative equity officer at Glenmede Investment Management, suggests there are still reasons for optimism. Entering this year, using price-book multiples, value stocks were as cheap relative to the most expensive stocks as they had been since the 1929 Great Crash: This chart compares the price-book multiple of the most expensive quintile of stocks to the least expensive. By the end of last year, the value spread was roughly five standard deviations above the norm, according to Atanasiu. Either the notion of buying stocks had died and there was no longer any point in looking at their valuations, or value stocks were primed to snap back. As we know, they snapped back. This doesn't mean that the opportunity is over. For large-cap stocks, Atanasiu puts the current value spread at 2 standard deviations above the norm — or roughly where it was immediately before the internet bubble burst and ushered in several years of value outperformance. Value and growth tend to move in cycles of about four years, driven by sentiment. But the current cycle has been unprecedentedly brutal, and very quick:  There is no limit on how quickly the rubber band can snap back at a time like this. The FANG stocks have corrected significantly this year, and this has helped to close what had been a phenomenally wide valuation gap. Where does this trend go from here? As with so much else, it depends on the central question of bond yields and the economy. If the economy really rolls over swiftly and rates come down, it will be time for the FANGs and other growth stocks to shine again. If not, investors might continue to shop for bargains. But everything is driven by bond yields which are still signaling an infeasible compromise between two mutually inconsistent outcomes. Keep an eye on the data.  | My unoriginal tip for today is that it might help your mental health to stay off social media. I've had some interesting responses after writing a few times about gun rights and the US Second Amendment in the last week, and I now know that a large contingent of people on Twitter sincerely think Australia is a "tyranny." For example, one poster attacked the gun control proposal by Justin Trudeau in Canada with these words: "Tyrants do this! Tyranny starts with this! Look at what happened in Australia!" What exactly was supposed to have happened in Australia? There are blots on Australia's history, of course, but the same is true of every country. It had never occurred to me that it was in any way tyrannical. Instead, I agree with Australia's self-label that it's "the lucky country" — a largely prosperous nation with a high quality of living. What were these people talking about? Further investigation reveals that they were talking about Covid, with reference to the aggressive gun control (carried out under a conservative government) after a mass shooting in Tasmania in 1996. The argument is that that effort made it possible for Australia to impose draconian anti-Covid measures in 2020 and 2021. It's certainly true that Australia was more restrictive than most countries (in part because geography gave it more of a chance of avoiding the worst of the pandemic), and that many Australians protested. But were these actions truly tyrannical? If we look at the two countries' homicide rates, Australia's was 0.9 per 100,000 in 2020, while the equivalent number for the US was 6.3. Turning to the Covid death rate, the US has suffered 306 per 100,000, compared to Australia's 34. In both gun laws and pandemic policies, we know there are tradeoffs. It's perfectly reasonable for an American to accept a far greater risk of violent or pandemic death in return for greater liberties; but the tradeoff Australia has made also seems to have worked out. If you want to prioritize life over liberty, Australia has delivered. Having said all that, I still haven't come to the key reason why it's absurd to call Australia a tyranny; it's just had an election, and the people peacefully voted out the government that had been responsible for the Covid lockdowns, and put a new team in. The changeover of power was without incident. That doesn't happen in a tyranny. For further signs of Australians acting freely as they wish, try Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, which is now quite an Australian institution. Or the generally liberated music of AC/DC, or Midnight Oil (who had a song called Put Down That Weapon), or Elephant by Tame Impala, or this special version featuring Australia's great band The Wiggles, as well as Tame Impala, in which Elephant segues into the Wiggles classic Fruit Salad (a song that reminds me how glad I am that the kids have grown up a bit these days). You can like or dislike Australia, or the USA. I love both. You can't call either of them a tyranny. More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? Terminal readers head to {OPIN <GO>}. |

No comments:

Post a Comment