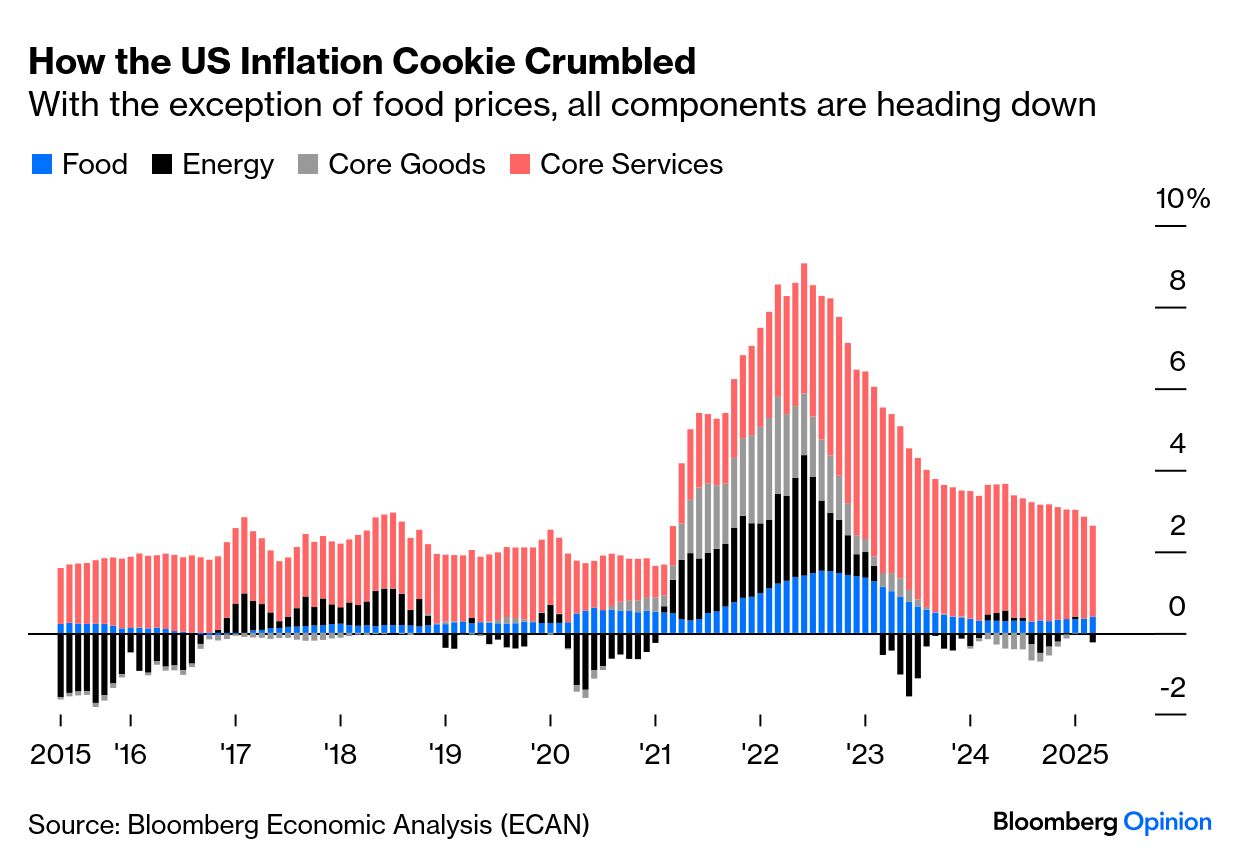

| Irony of ironies. On a day when the battle to save the value of the dollar in the pockets of US consumers seemed finally to be won, its value to everyone else sank. Inflation is yesterday's news, it appears, and the currency's fate is now driven by confidence and the uncertainties surrounding tariffs that are yet to affect prices. The consumer price index data for March, announced Thursday morning, were about as good as anyone could have reasonably expected. This is how it broke down into its four main components, as tracked by the handy ECAN <GO> function on the terminal:

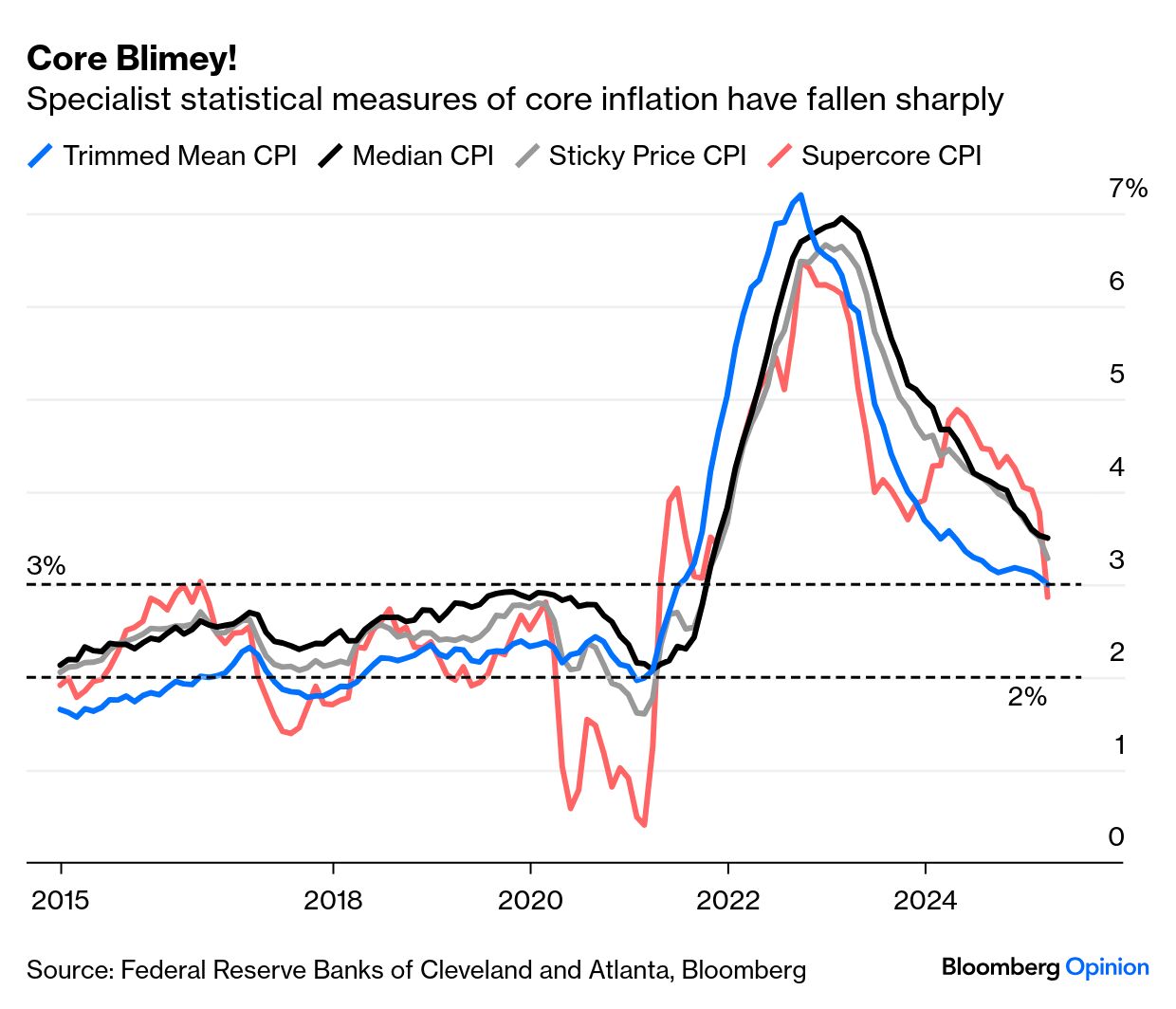

Food inflation ticked up a little, and politically sensitive eggs rose at 60.4% year on year, but overall core measures were remarkably healthy. Sticky prices, on products whose prices are difficult to move, dropped to the lowest rate since early 2022. The trimmed mean and median measures both fell, showing disinflation was broad-based, while the "supercore" measure of services excluding shelter, much emphasized by the Federal Reserve, has suddenly tumbled below 3%:

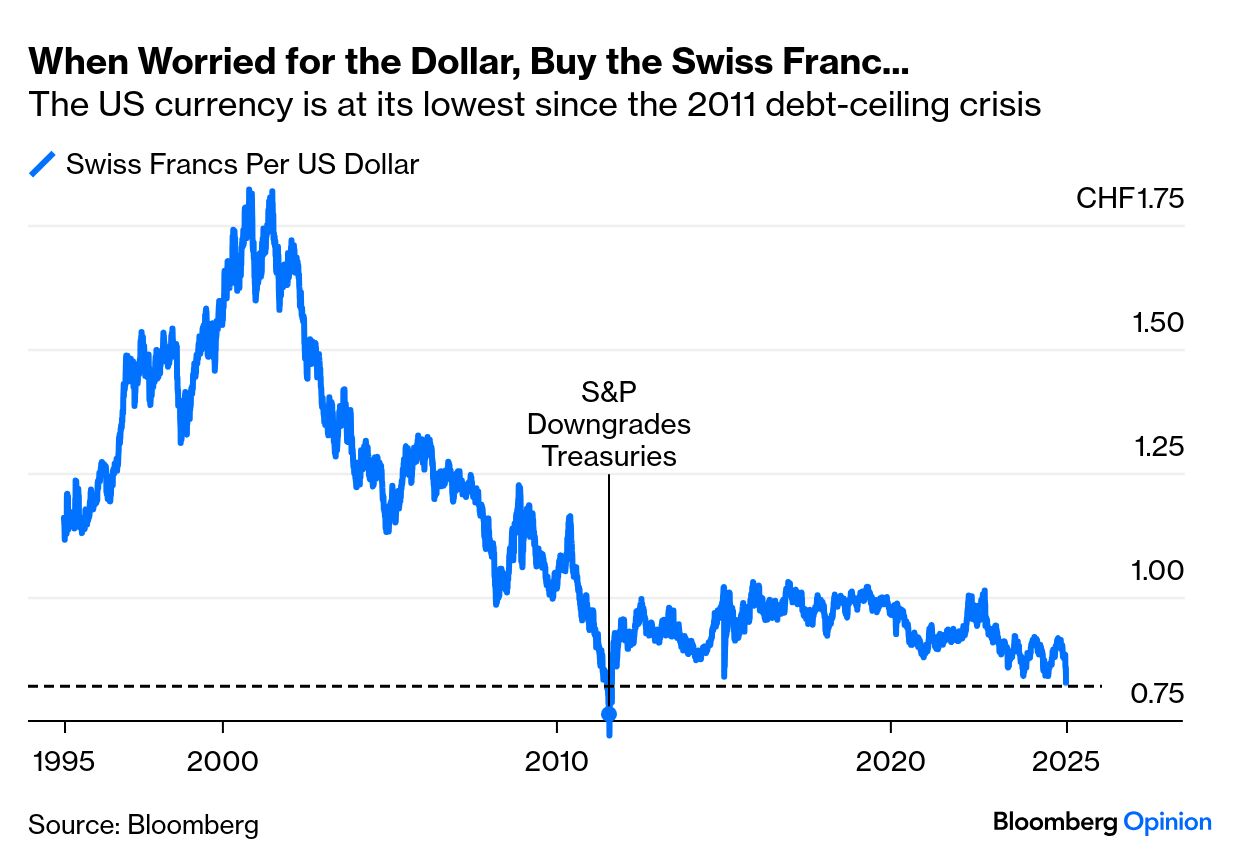

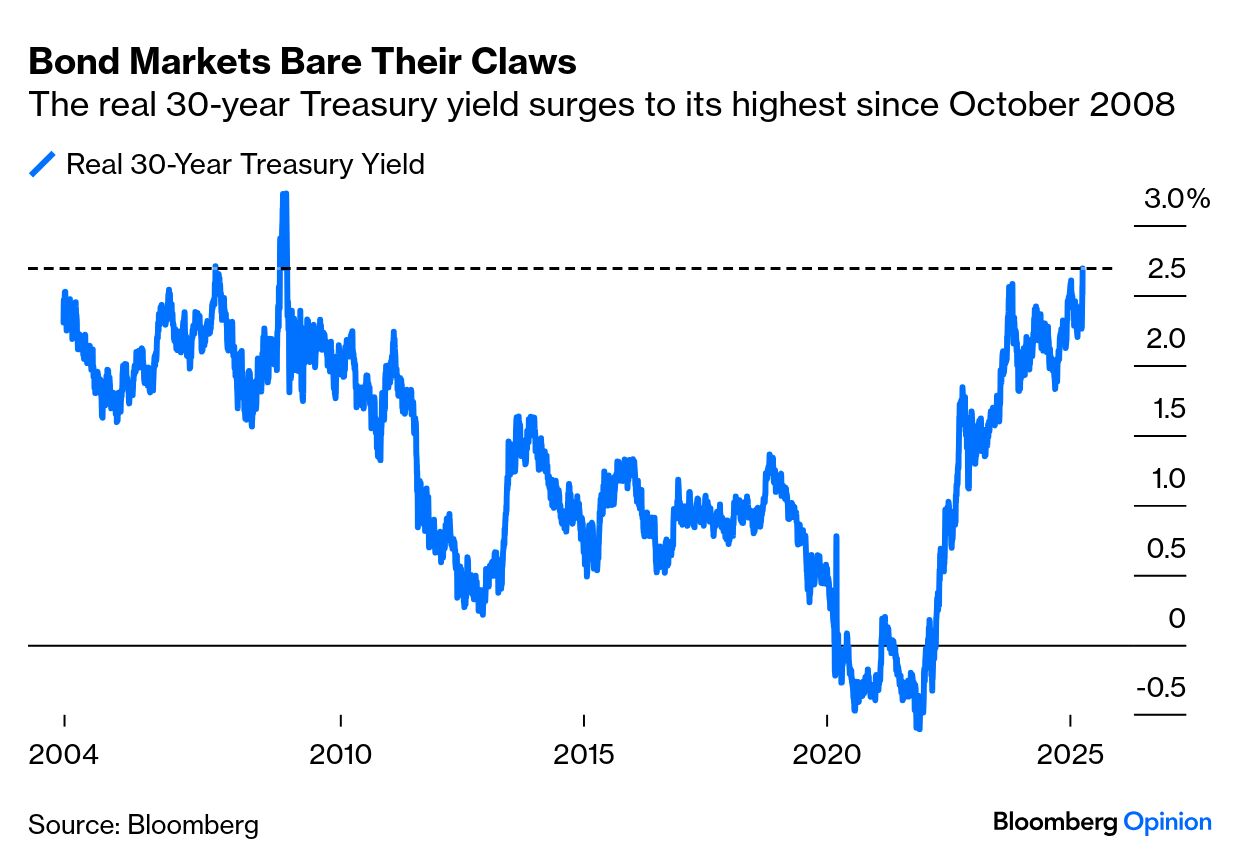

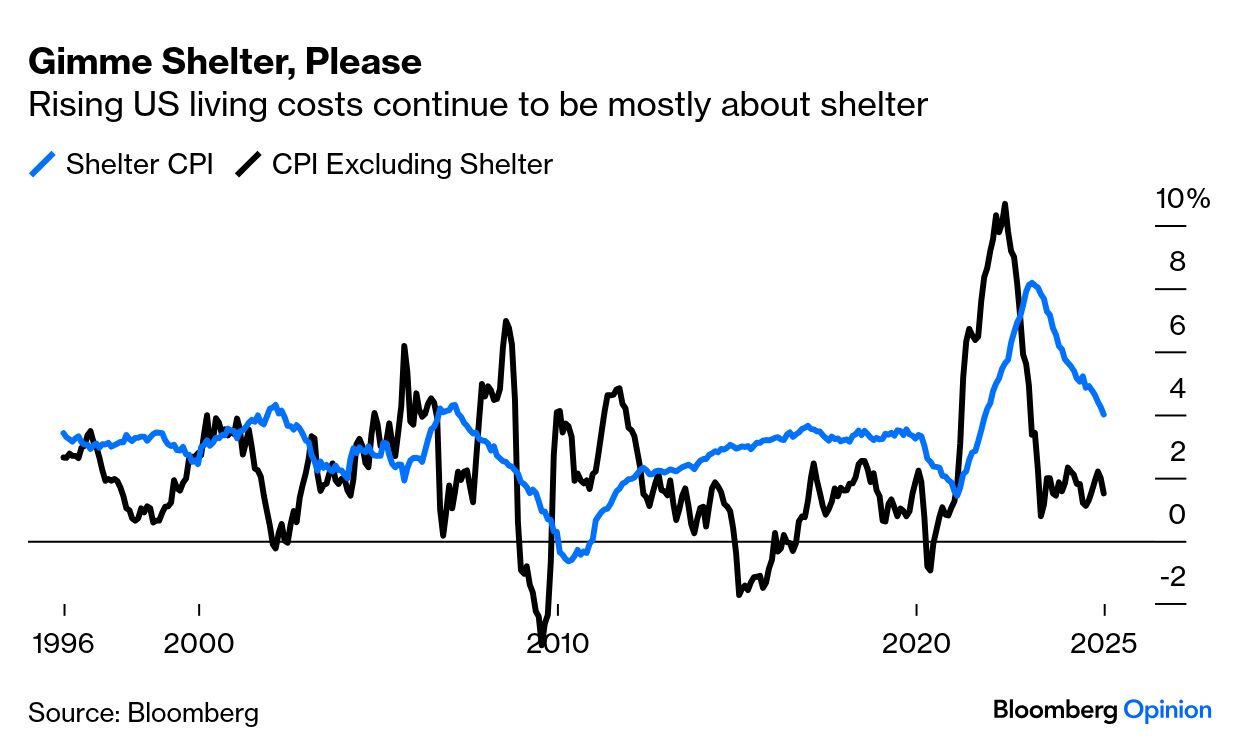

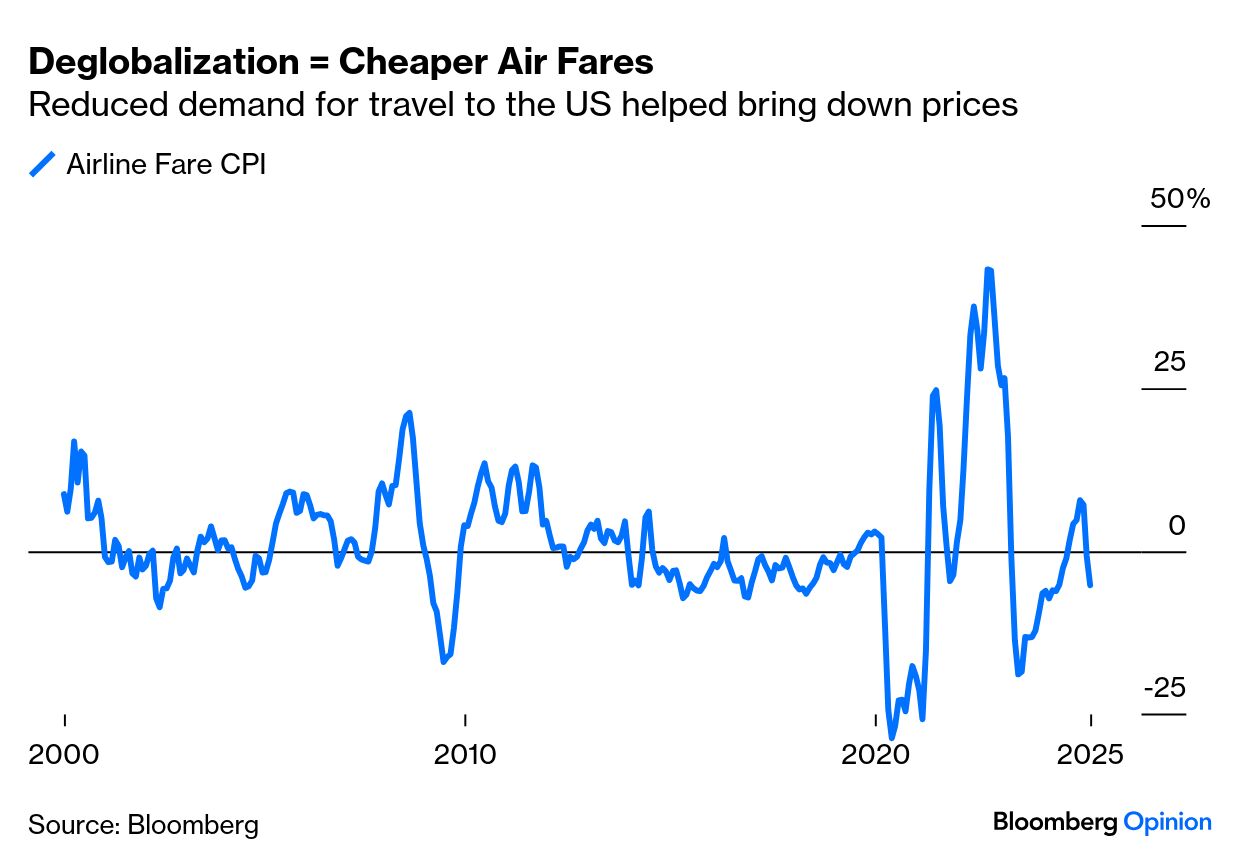

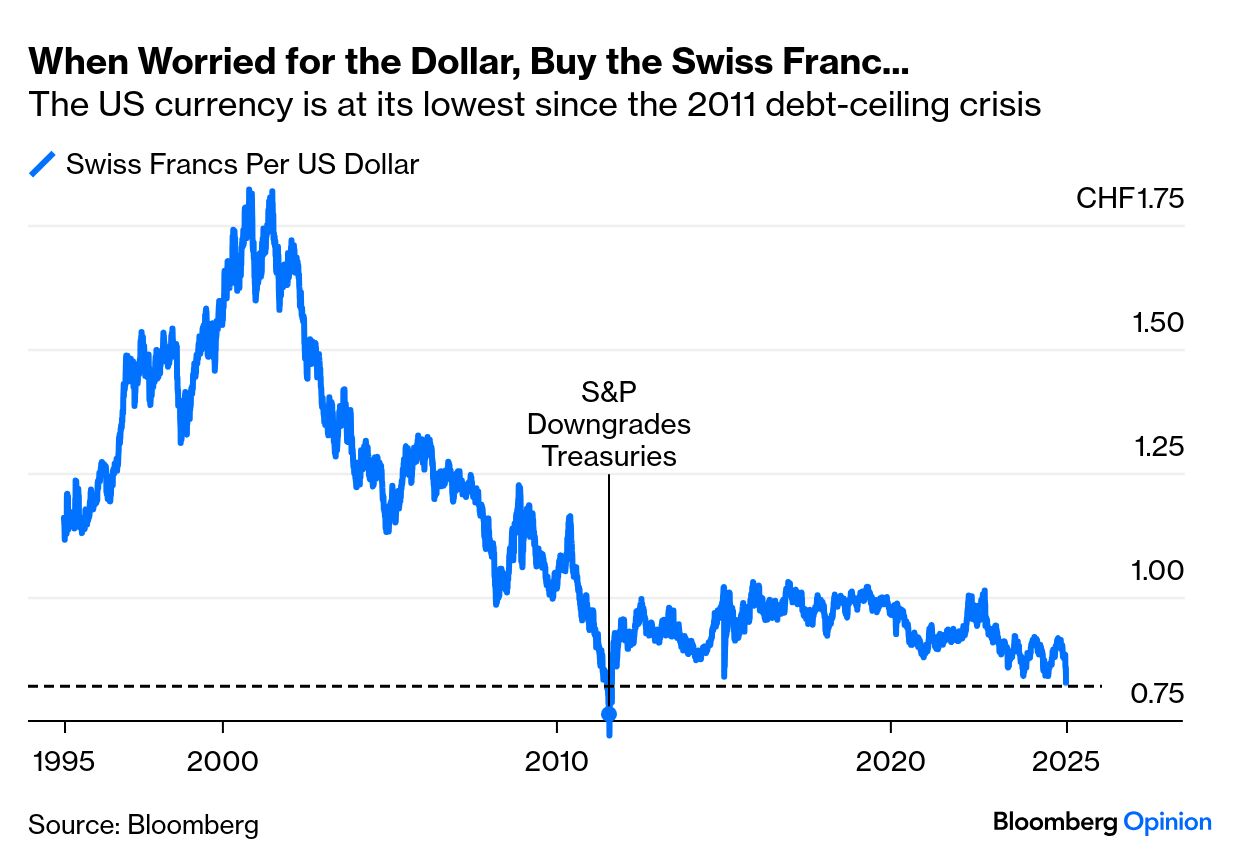

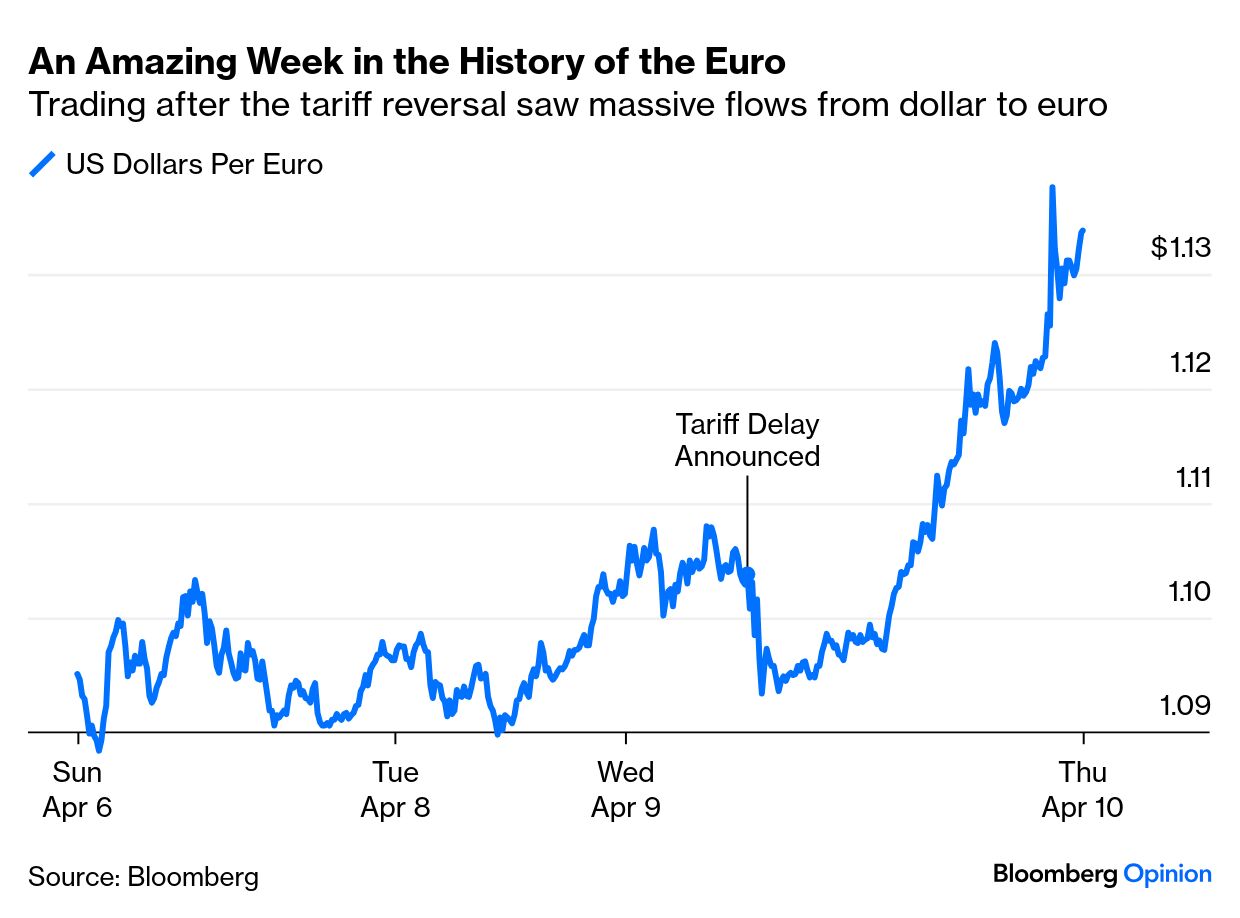

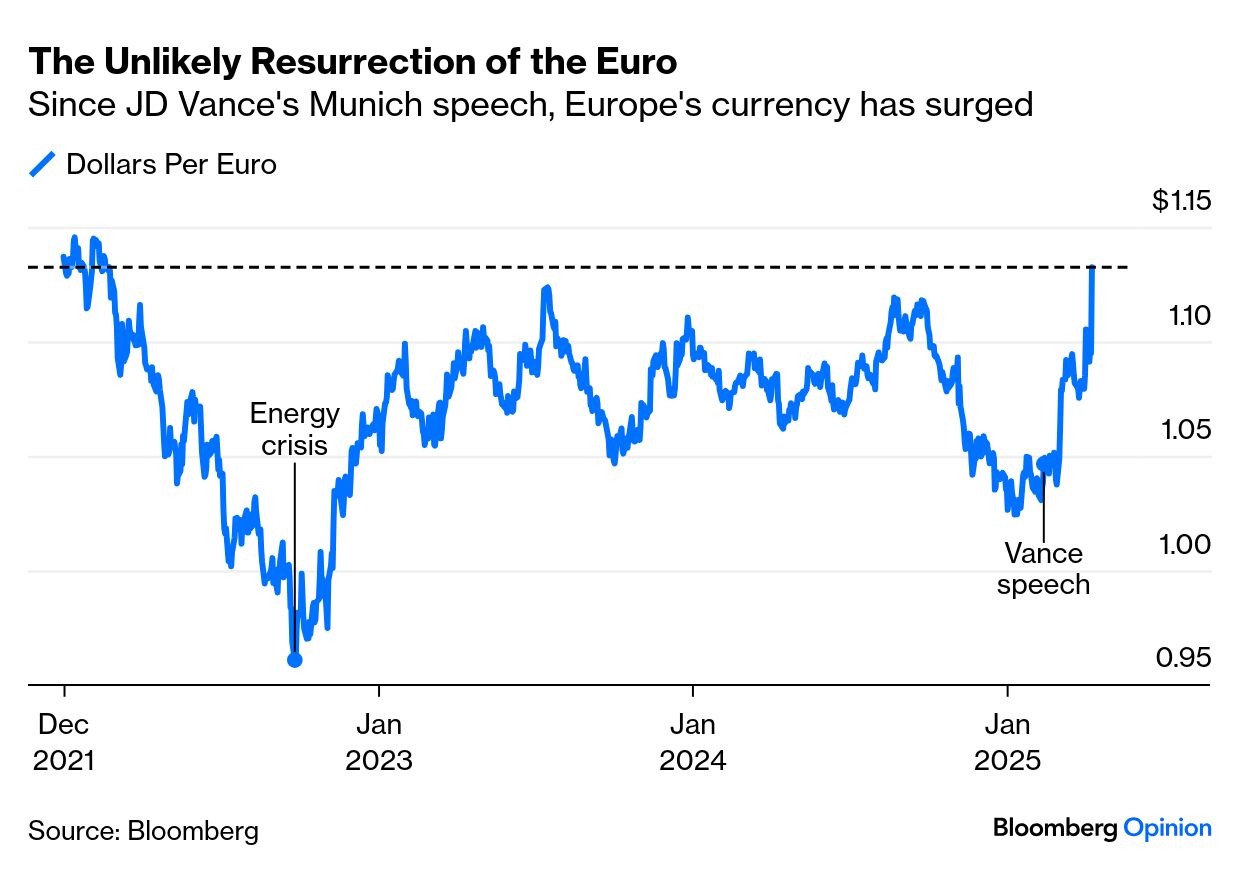

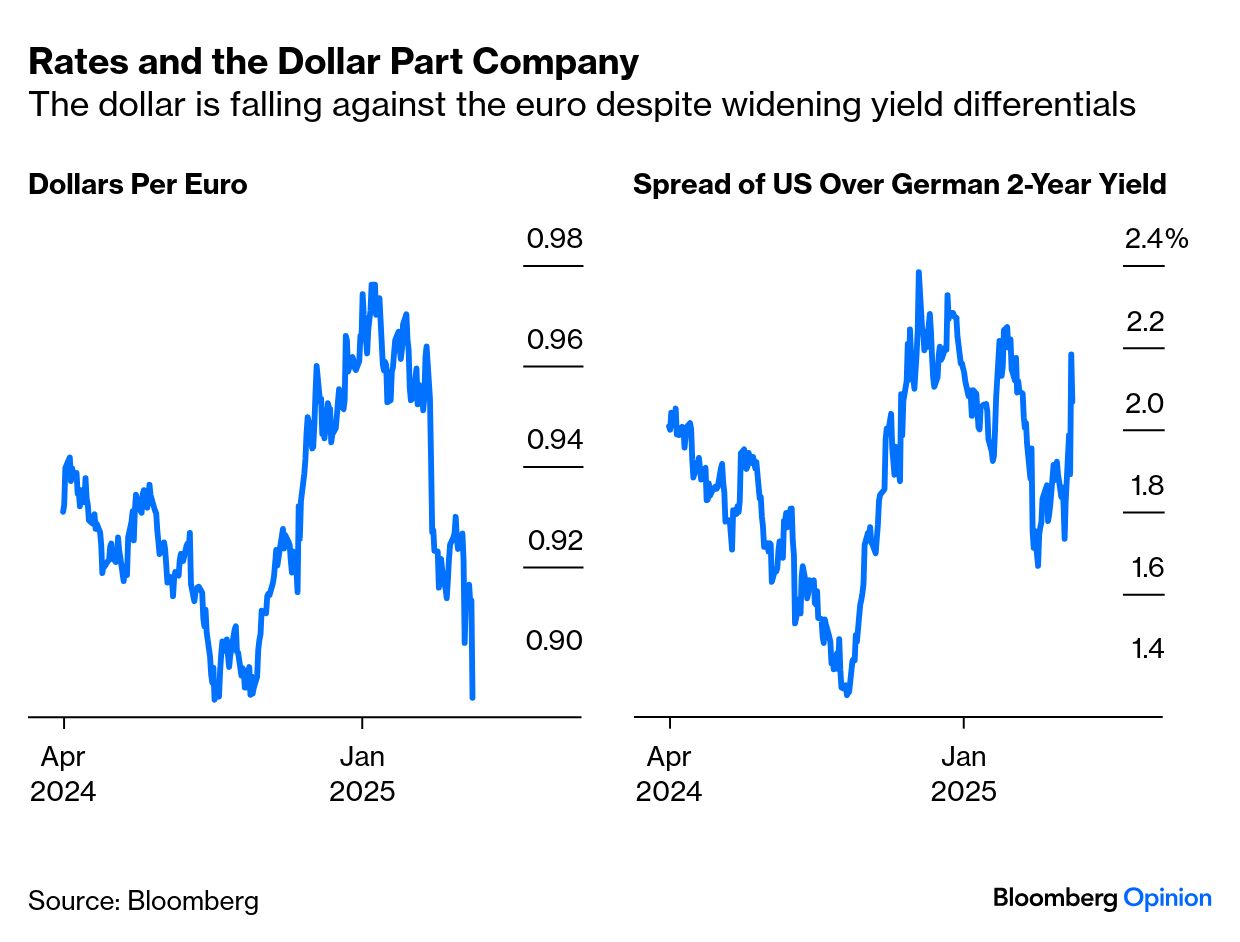

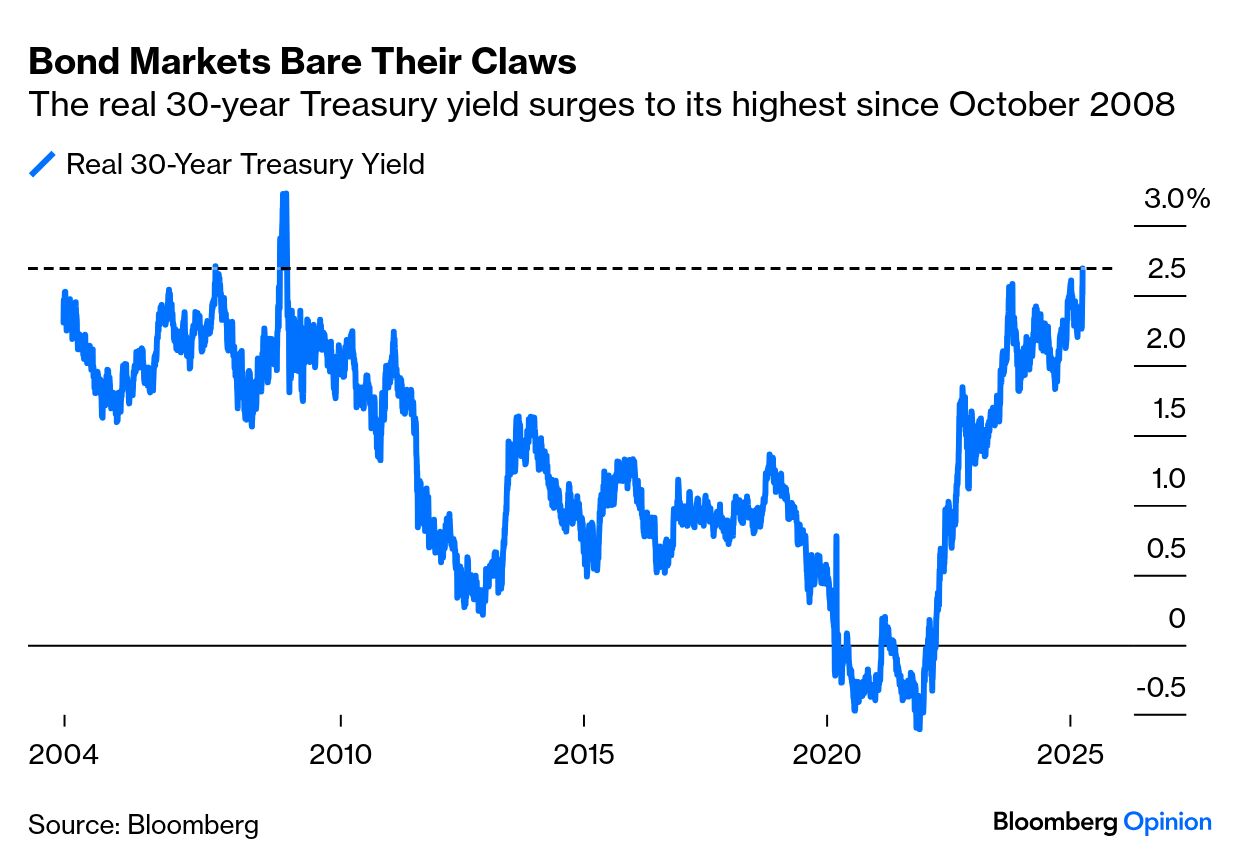

Shelter, central to the crisis in living costs and main driver of the overall index for the last two years, dropped below 4%; exclude it and the rest of the index is inflating at less than 2%: If there is any carping to be done, it's that the reduced price pressure owes much to a slowdown in activity driven by the early actions and pronouncements of the Trump administration. Air fares fell, surprisingly, while hotels in the northeastern US had to reduce their rates — both probably attributable to Canadians' new-found aversion to visiting their neighbors to the south: Put together with last week's employment numbers, which were also surprisingly strong, the economy is in better health than most had thought three months ago. Inflation is almost back within its target range and employment is still rising. How, then, to explain what happened to US markets in the hours after these numbers were released, and particularly to America's financial flagship, the dollar? When the US does something truly self-defeating and stupid, the natural response of currency traders is to seek an Alpine sanctuary. The Swiss franc is regarded as the safest of havens. So it's significant that the dollar just endured its worst day compared to the Swissie since 2015, falling more than 3% to take it to a level last touched during the debt ceiling debacle of August 2011. On that occasion, dysfunctional policymaking in Congress prompted Standard & Poor's to downgrade Treasury debt, and that briefly led to an exodus:  Essentially, the US very nearly decided to default on its debt when it didn't have to. The latest rush to the Swiss redoubt suggests that the market thinks that the Liberation Day tariffs, subsequently retracting some of them, and the scarcely credible 145% levies on Chinese goods constitute the stupidest acts of US economic policy since then. The selloff intensified in Asian trading. At one point, the dollar had dropped more than 5% since Wednesday's announced climbdown over reciprocal tariffs. All of this after the good news that the dollar was retaining more of its value at home, thanks to lower inflation. More remarkably, the European economy is far weaker and the euro zone is under intense pressure — yet traders behaved as though the euro was almost as reliable a haven as the Swiss franc. The euro's surge has been remarkable since US Vice President JD Vance's speech to the Munich security conference suggested that the US-European alliance was over in its current form: One logical explanation for a weakening dollar after strong inflation numbers would center on bond yields. All else equal, lower inflation makes it easier to cut rates, and will bring down short-term yields. The differential between two-year yields has been a key driver of the exchange rate and lower US yields should mean a weaker dollar. The problem with this theory is that the differential has widened sharply in the US favor of late. The dollar's slump has come as Treasury yields have risen sharply above German bunds — itself a remarkable occurrence only weeks after Germany committed to its biggest fiscal expansion in generations (largely in response to the Vance speech as it decided it could no longer treat Washington as a reliable ally): Short-term yields are more important to the currency, but the move in longer bonds has been more startling. The real 30-year yield, as pure a measure of the cost of long-term money as exists, has now reached a high only previously seen during the spasm that followed the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008:  It's hard not to write about this in terms that sound apocalyptic. But it's also hard to cast this as anything other than a significant loss of confidence in the US. It doesn't have to be terminal. The shock of the debt-ceiling crisis in 2011 turned out to be a major turning point that was followed by a decade of American Exceptionalism. But the moves in the bond and currency markets — to a far greater extent than stocks (which by the way endured a massive selloff Thursday and gave up more than half of Wednesday's gains) — ram home that a lot is at stake. And the US is currently embarked on what appears to be a wholesale change in foreign policy, not struggling to get things back to normal as Barack Obama tried in 2011.  Getting back to normal isn't in the playbook. Photographer: Shawn Thew/EPA How could this crisis of confidence come just as the US has come through its inflation trial? The problem is that almost all economic data is now coming off as backward-looking. Nobody cares. Similarly with the corporate earnings season, kicked off Friday morning by the big banks, there will be minimal interest in how things went in the first quarter. All now depends on what CEOs have to say about how they'll live in a new world in which the US and China have effectively imposed a trade embargo on each other. Is anything more sinister afoot? It's possible that some large hedge fund is in trouble, and likely that central banks and sovereign wealth funds are having a role in driving these moves. That wouldn't necessarily be motivated by politics; they might simply and prudently be deciding to scale back exposure to the US. And as Points of Return has pointed out, international exposure to American assets is historically high, so such a move could go on for a while and become self-reinforcing. |

No comments:

Post a Comment