| It's conventional wisdom that deeds matter more than words. That buttresses the continuing optimism over trade policy: For all his protectionist invective, Donald Trump has announced delays or retreats on most of his tariffs. There are exceptions. The Federal Reserve often uses the power of the jawbone and what it says matters a lot. If people react to a warning, the Fed can even have its desired effect without needing to do anything. Because central bankers have to mind their words, mere choice of subject can be most significant. For a prime example, Fed Chair Jerome Powell triggered a big afternoon selloff by talking frankly — but without saying anything anyone didn't know — in a discussion at the Economics Club of Chicago. He admitted that there "isn't a modern experience for how to think about this:" Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well-anchored and to make certain that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem. We may find ourselves in the challenging scenario in which our dual-mandate goals are in tension

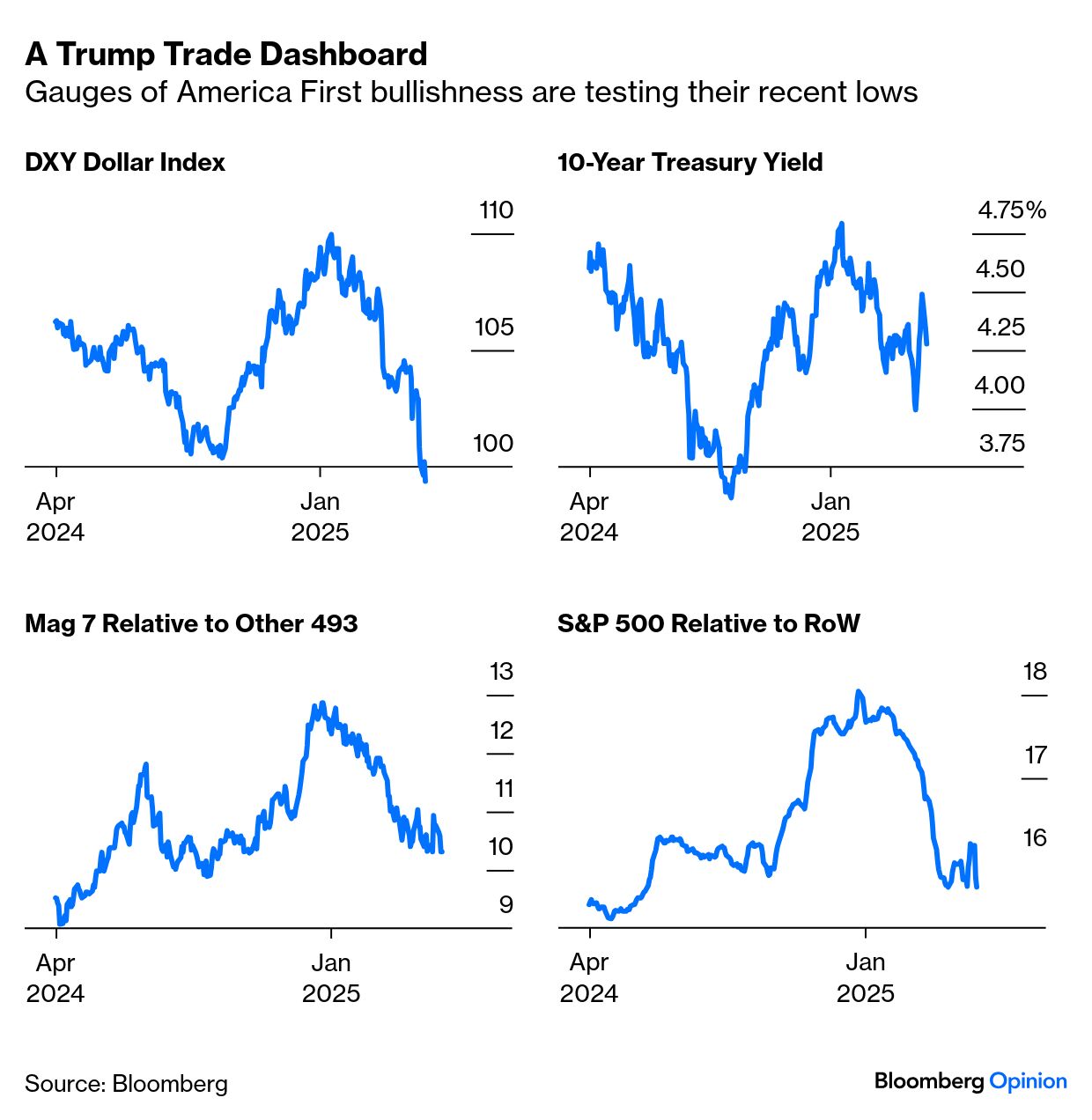

More or less everyone is alive to the risk that tariffs could both raise inflation and lower growth, and hammer both sides of the Fed's mandate. The fact that Powell said so, however, along with the explicit assertion that higher prices due to tariffs might push up inflation expectations, was a sign that he wouldn't resort to rate cuts at the first sign of trouble. He might easily have dropped such a hint — and many traders were furious with him for not doing so. Equities, led by Big Tech, sold off after he spoke, as did the dollar. Amid much excitement, the main elements of US exceptionalism, are back to testing their post-"Liberation Day" lows — but at least Treasury yields are falling again: Central bankers' mere words do indeed matter. But do we need to note what politicians are saying? Normally, their deeds matter far more. There have been exceptions of late, however, particularly when coming from the mouth of US Vice-President J.D. Vance. In February, he made an epochal speech in Munich, lacing in to European leaders to say that they were more threatening than Vladimir Putin's Russia. Two weeks later, there was his equally famous berating of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in the Oval Office. Nobody was hurt in these exchanges, but they had consequences. After the Vance speech, Points of Return was headlined "There's No Template for the Shock Europe Just Got" and described it as a major geopolitical event. That prompted some pushback from the US. One reader said that the column had taken on a "tilt" and added: The intransigency of the European state appears to require strong rhetoric to even dent their narrative. They are words, Europe is overdue to act.

That's a reasonable response, but not to the message that Vance actually delivered. He didn't read the riot act over defense spending — which would have been reasonable — but made such a wide-ranging attack on Europe and all it stood for that his listeners decided the US could no longer be trusted as an ally. The subsequent boost to defense spending in Germany isn't to make sure it keeps its NATO commitments, but to ensure its independence from the US. And as we've written at length, that's had massive financial impacts. The Munich speech is only the biggest example. People don't like being insulted and hate criticism from foreigners. Describing the Chinese as peasants gifted propaganda to the US' prime trade adversary, and helped it to muster support in its population. It's now a Chinese condition of talks that the US shows respect, which is fair enough. If you want to make a deal with someone, don't insult them first. Vance's response to the British and French proposal to send peacekeeping troops to Ukraine — dismissing the efforts of "some random country that hasn't fought a war in thirty of forty years" — led to a furious response, particularly from his more natural supporters on the right, who have also noted that US conservatives are criticizing Winston Churchill. UK forces fought alongside the US in Kuwait, Afghanistan and Iraq. This came across as a specious insult, impeding US aims to get Europe's powers to step forward in their own defense. The administration has as yet done nothing to back up its interest in seizing Greenland, but Vance's trip there appeared designed to create the greatest possible insult. Denmark's people already felt grievously affronted. And while the Trump administration wants to add Canada as a state, the leadership's deliberately offensive words have triggered an economic backlash. It's harder to grasp this from the US, but this language has done lasting self-harm. As my old colleague Katie Martin pointed out in the Financial Times, trust is lost, and the US is now open to ridicule. It's not often that mere words do matter. But US discourse has been so aggressive and offensive as to sunder long-lasting alliances, and forestall the possibility of a rapprochement. |

No comments:

Post a Comment