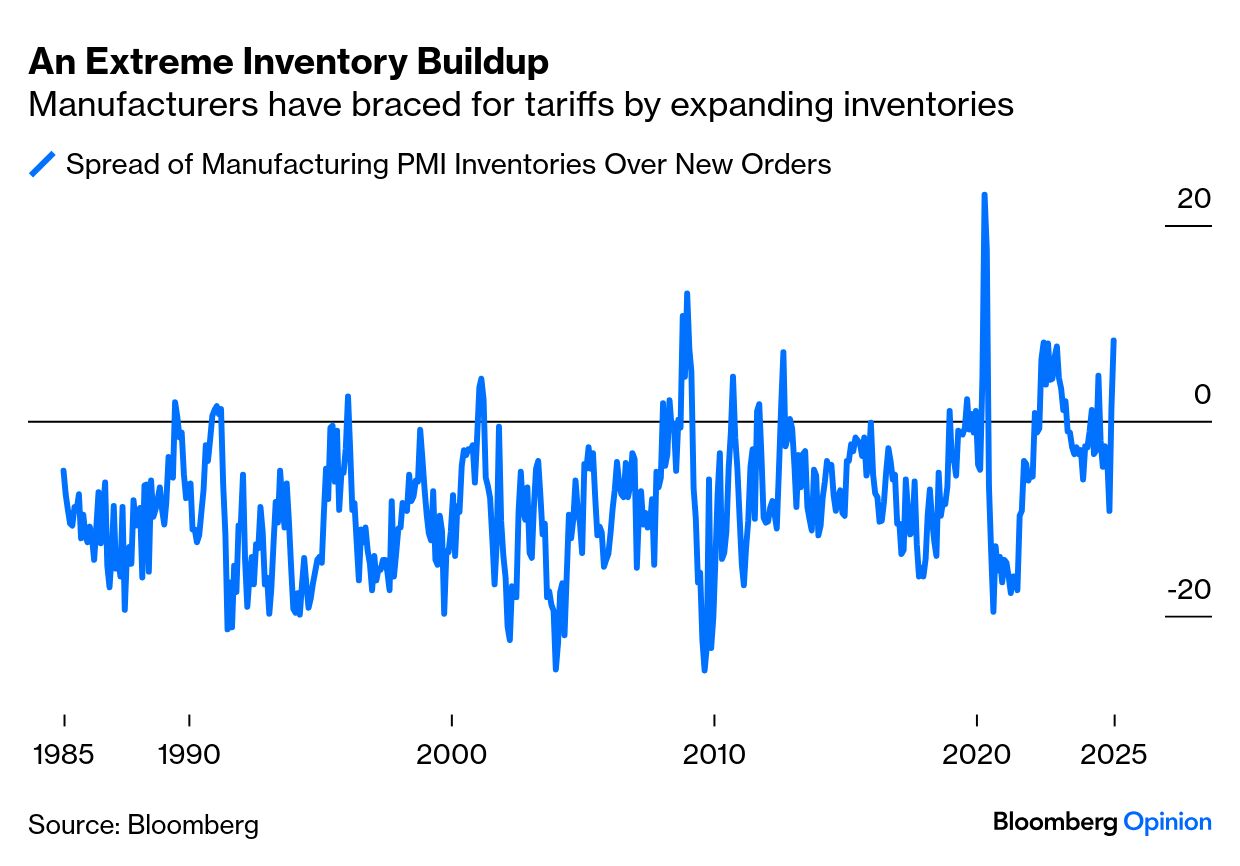

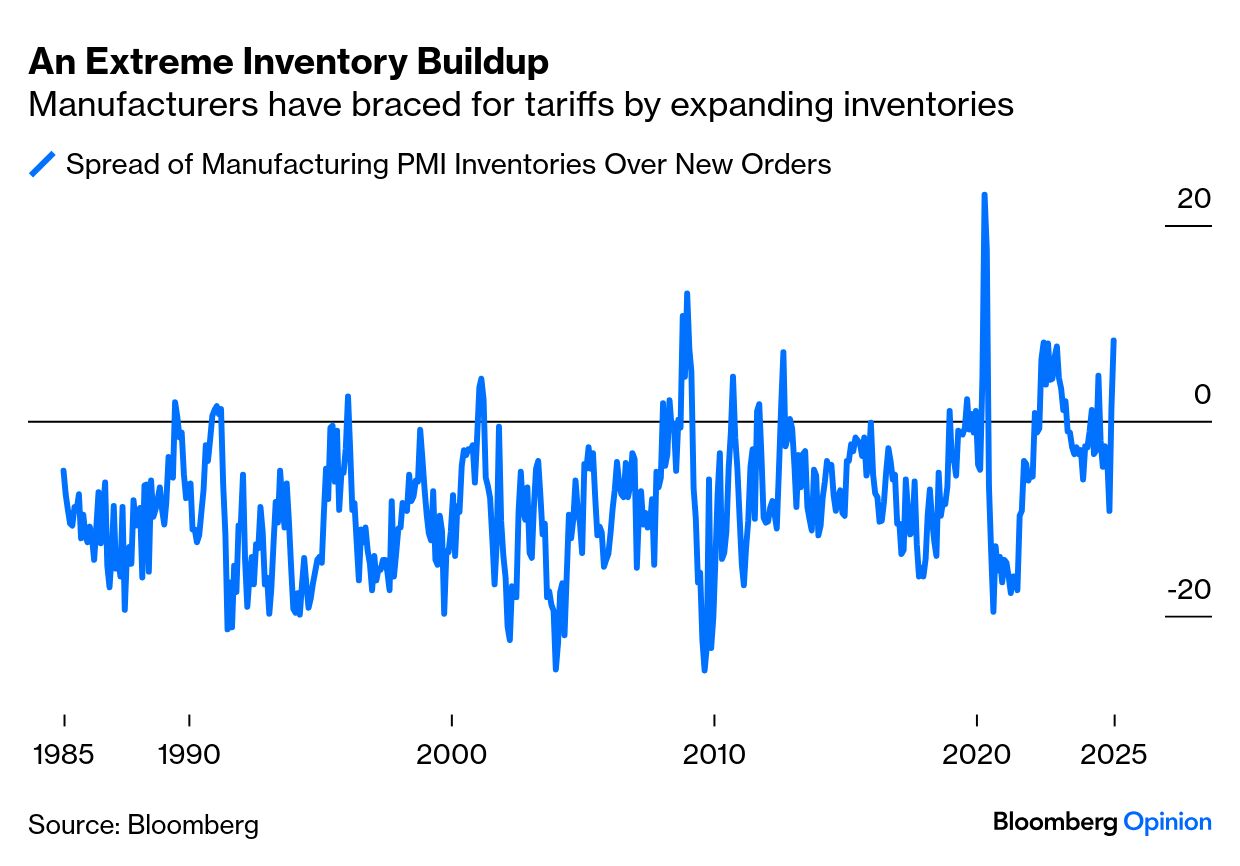

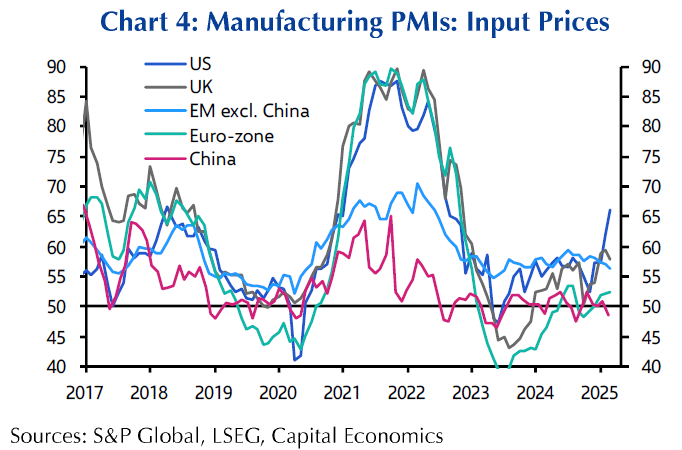

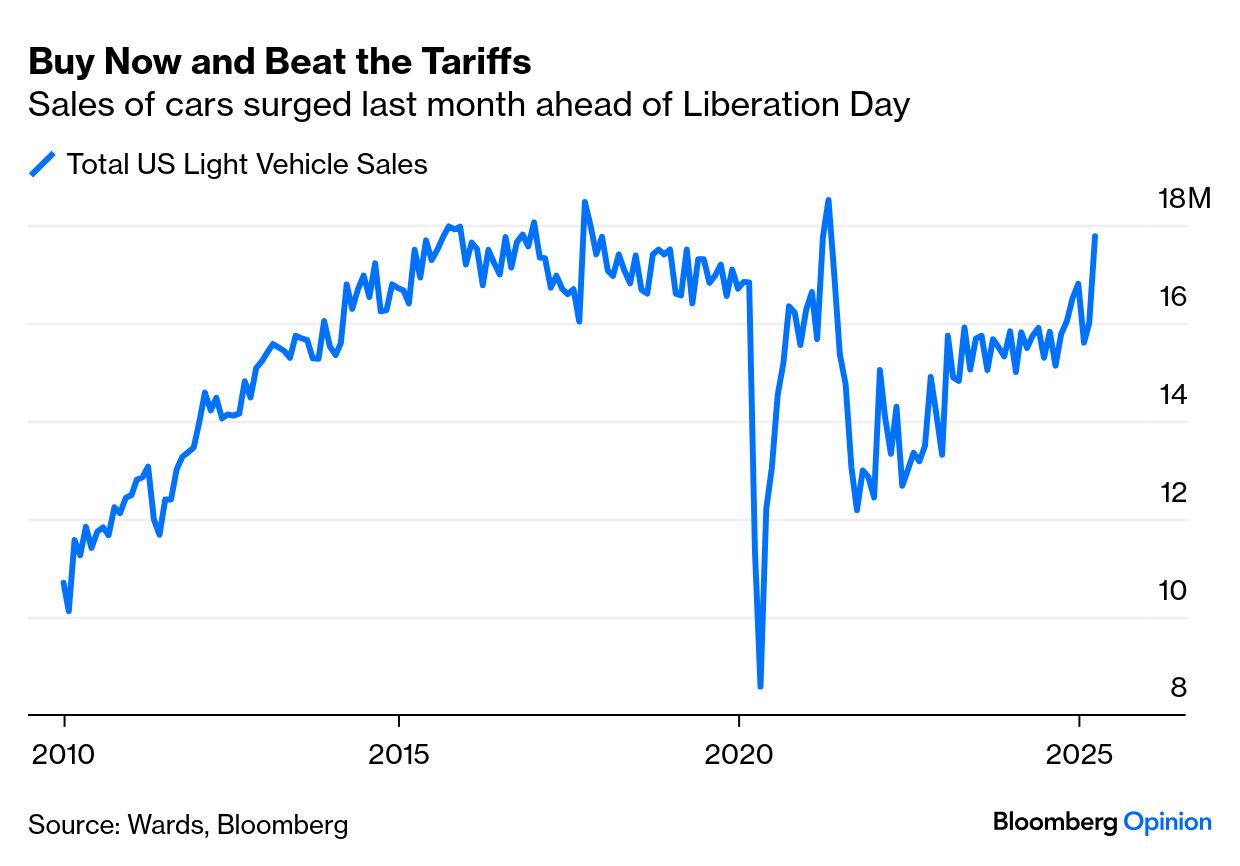

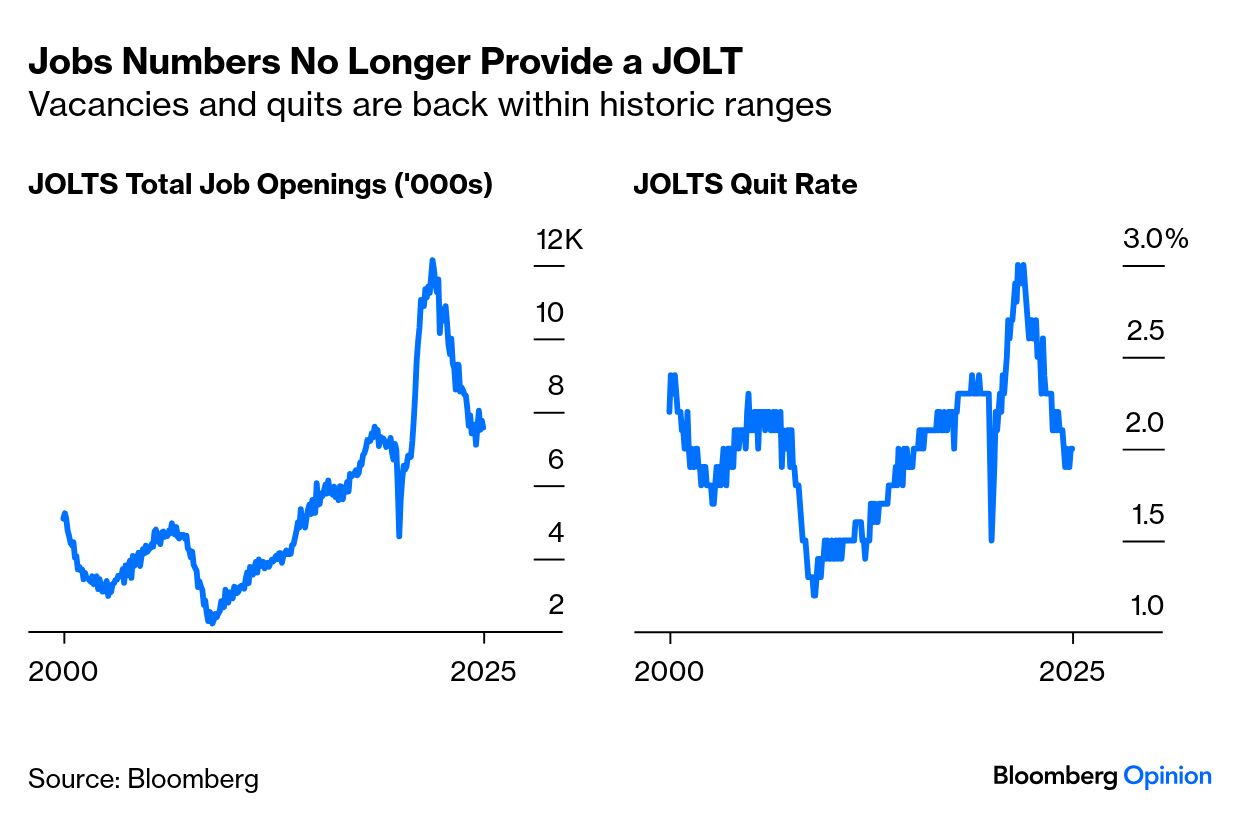

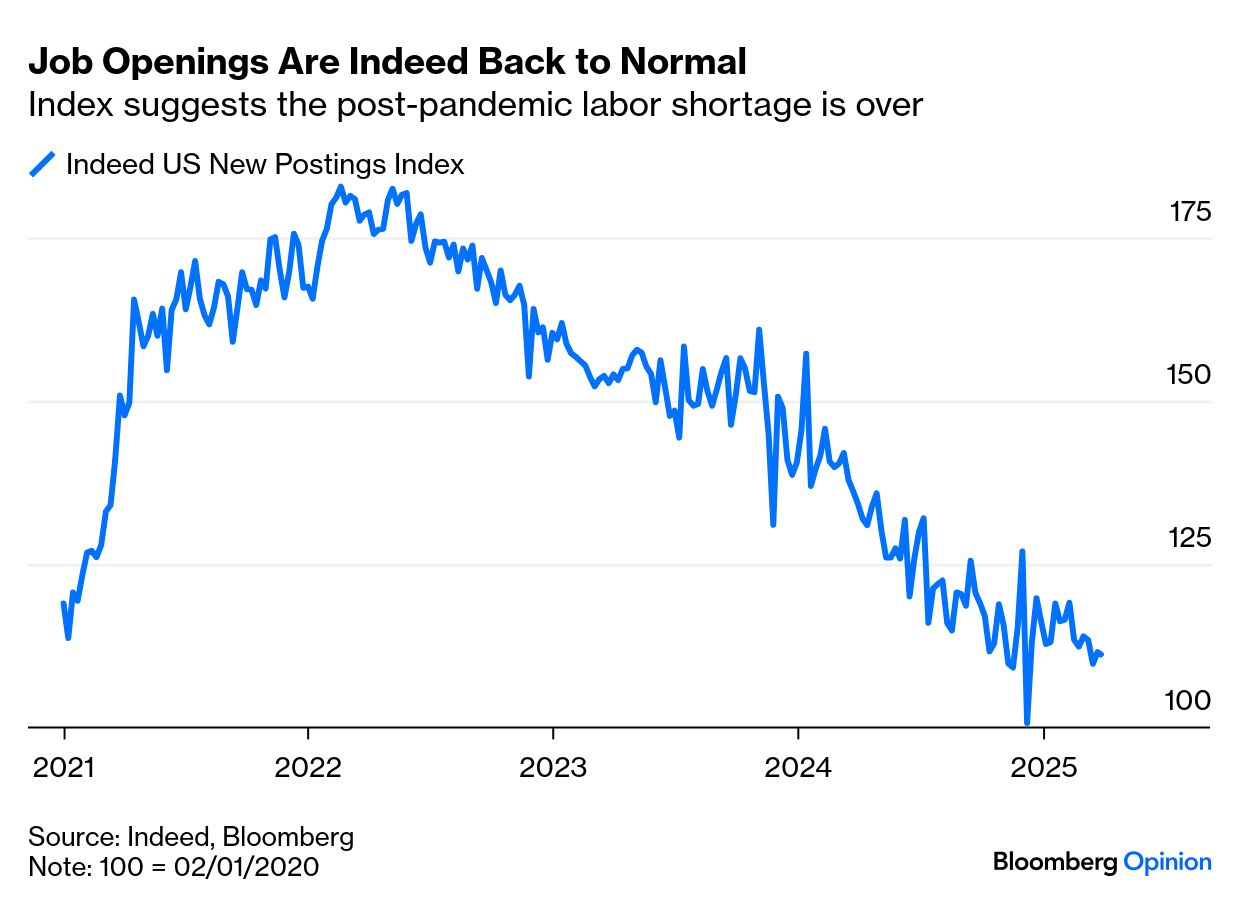

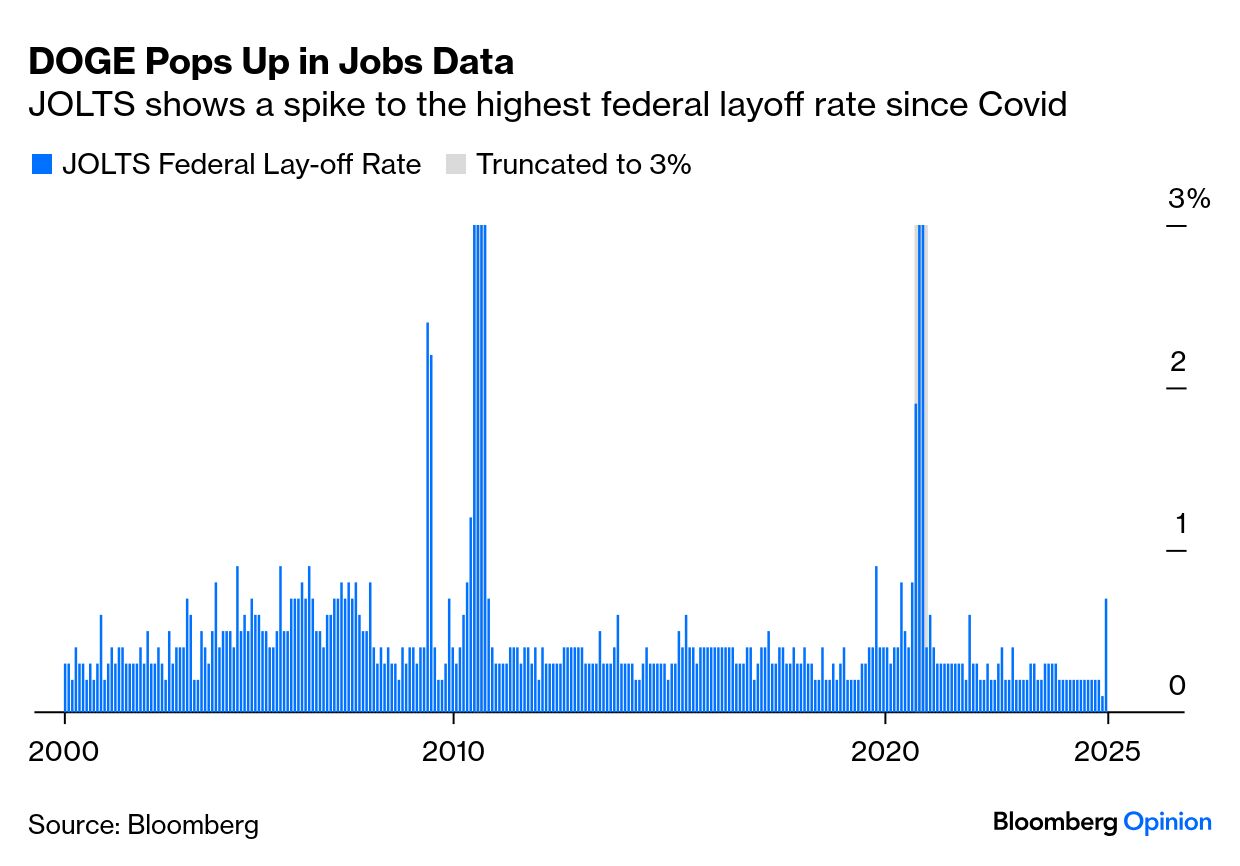

| The Liberation Day hype has already had real-world consequences. That was clear from the latest Institute of Supply Managers survey of US manufacturers, published Tuesday. The overall number fell, suggesting a growing risk of recession. But the eye-catching data came on the balance between new orders and inventories. As the chart shows, inventories exceed new orders by the greatest amount in four decades, with the sole exceptions of the worst months of the Global Financial Crisis and the Covid lockdowns:  This is not healthy. If companies have a lot of stuff on hand, and few orders, they will likely do less business and activity will fall. By contrast, when inventories are low, there's a chance of a restocking boom as companies ramp up to meet demand. On this occasion, tariffs are an obvious explanation. Companies brought forward their imports to beat duties. They now have excessive inventories and the odds are that they'll be reducing production in the months ahead. That could be a total blip when it turns out tariffs don't change the landscape much; it might be transitory, as they soon return to old practices but now paying tariffs on goods they import; or it might prove to be a lasting change. On its face, however, it's bad. The other disconcerting reading was on the prices-paid component of the index, which shot up, much as in 2021 when inflation was taking root. Tariff uncertainty is the likely explanation as companies fight over prices ahead of possible duties. What's most interesting is that while US manufacturers are having to pay more for inputs, their counterparts in the rest of the world are not. This chart is from Ariane Curtis, senior global economist at Capital Economics: Manufacturers elsewhere will have to await news on retaliation by their own governments, so it makes sense that the US encounters this issue first. For now, it makes US assets less attractive, and points toward a nasty dose of stagflation. Retaliation can be expected to turn the other lines upward. Consumers are also bringing forward purchases to beat tariffs. Last month's vehicle sales were the best since the brief boom after the pandemic. It may be best to assume this is early rather than additional consumption: The government also released the start of a welter of data on the jobs market. The JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) arrives with a lag, but it tended to douse concerns about either inflation or a recession. Total openings are down from the post-pandemic extreme, meaning that inflationary wage pressure should decline, but the quits rate, regarded as an indicator of how confident workers are, has returned to normal levels: Less-lagged private sector surveys confirm this picture. The index of new listings kept by job-search site Indeed shows vacancies right back where they were four years ago. That should make life easier for the Federal Reserve: The known unknown is the impact of the DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) layoffs. The JOLTS federal government layoff rate has just jumped to its highest since Covid. This remains far below the level during the pandemic, or from 2010 when government cut back in the wake of the crisis. It could prove transitory. But it's a point of concern: Standard Chartered's Steven Englander suggests that unemployment numbers could be affected by a bad winter that left many workers unable to work due to weather, while another signature Trump policy, an immigration clampdown, will also affect payrolls gradually. There's surprisingly good news from Europe. The latest inflation data, despite the money being splashed around there, are truly encouraging. Core inflation is close to the European Central Bank's target, while services inflation has dropped to 3.4% (in the US, it's still at 4.1%). If there's a need for relief from the ECB in the months ahead, in the form of lower rates, it looks as if it will be available. |

No comments:

Post a Comment