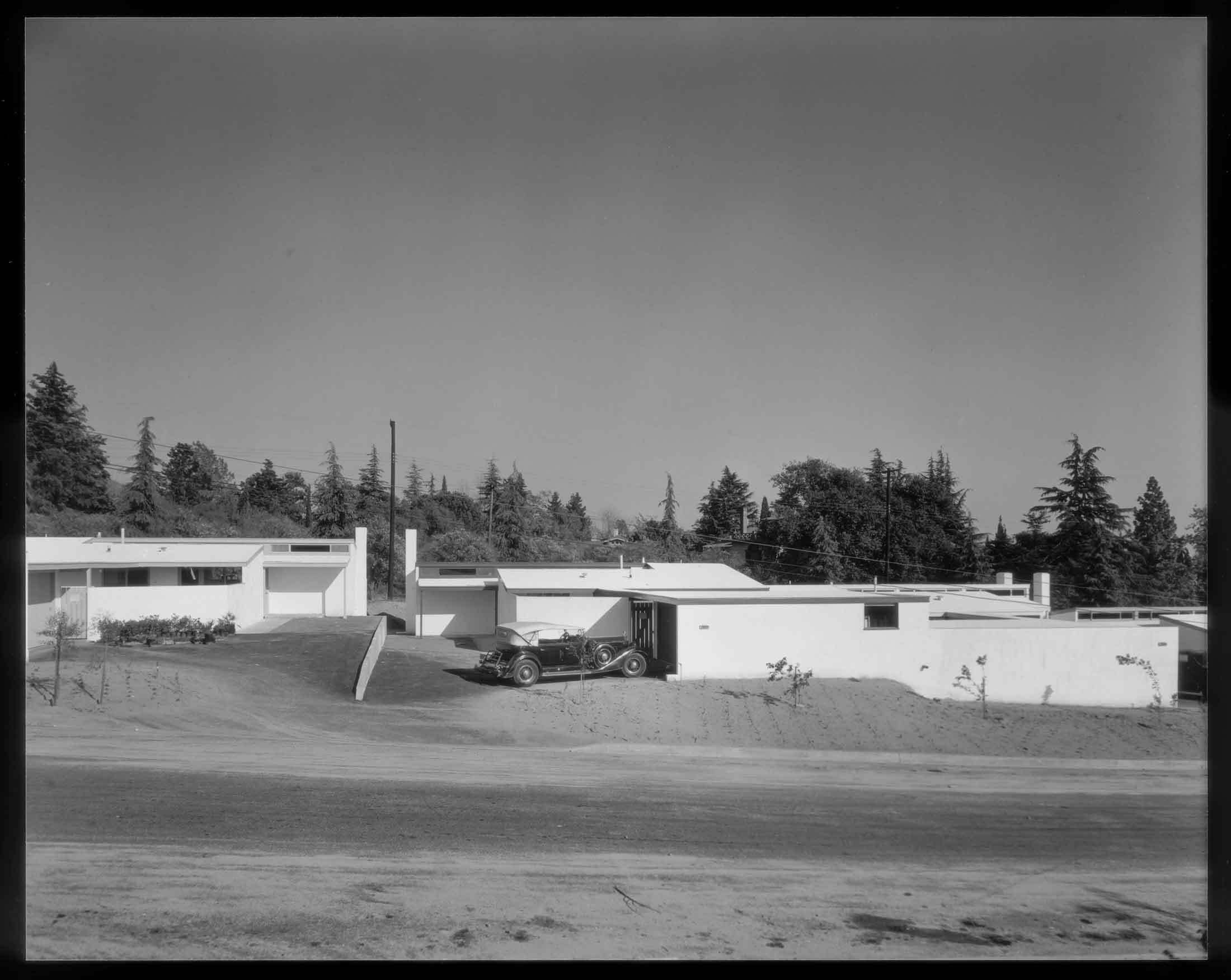

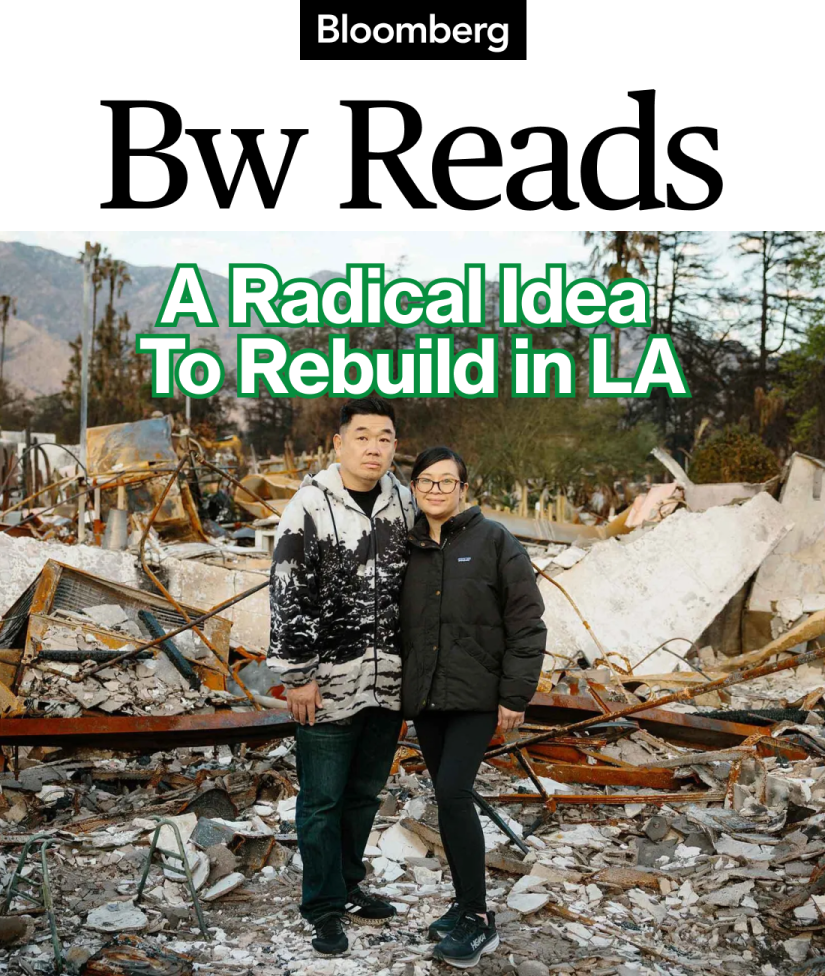

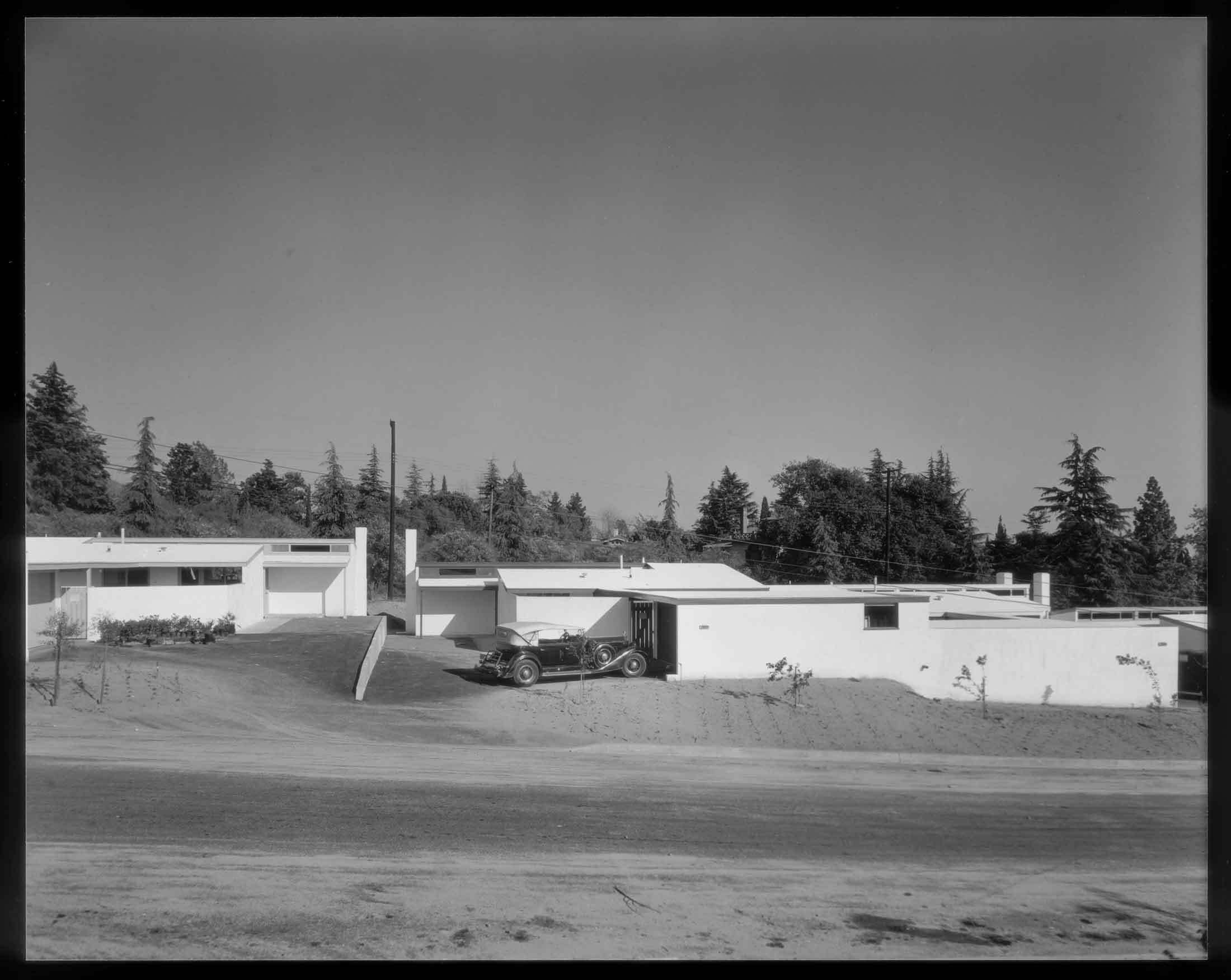

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today we travel with Businessweek editor and writer Laura Bliss to Altadena, California, where a group of neighbors is looking to restore a piece of Los Angeles' architectural history while rebuilding from January's wildfires. You can find the whole story online here. You can also listen to it here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. Kim and Chien Yu's love story began with a giant dalmatian costume. Kim was donning the head of a Sparky the Fire Dog suit for a public awareness day at the Pasadena Fire Department when she spotted Chien, a former high school classmate turned firefighter. Kim, who'd recently started a job as a hazardous materials inspector for the city, struck up a conversation—easy to do in the guise of a friendly canine. Their shared history led to a date, and within a few years they married and had two sons. In 2018 they bought a house a few doors down from one of Kim's co-workers, Phyllis Lansdown, who'd always raved about her block on Highview Avenue in nearby Altadena. "I would just joke about how, 'Oh my gosh, it would be so amazing to live on your block someday,' " Kim says. "And then we found ourselves being neighbors, and it was everything that she said it was and more." What the Yus found was a mix of residents who were old and young, racially diverse and largely middle class. It was a microcosm of Altadena at large and a remarkably faithful reflection of how the block had been envisioned decades earlier. Gregory Ain, a modernist architect who'd trained under luminaries such as Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, had designed the tract of 28 houses after World War II as affordable homes for working families, with fence-free landscaping and mirror-image driveways that nurtured greetings when people came and went. Seventy years later, barbecues and holiday parties still rotated through the shady backyards and open-plan living rooms. Boxes of collard greens, citrus and apples would sit out on neighbors' porches, homegrown harvests offered to passersby for the taking. The identical layouts of the homes put kids at ease on playdates. "It was a cultural utopia for us," says Kim. Then, a little after 6 p.m. on Jan. 7, a fire ignited in a canyon a few miles to the east. Chien needed to report for duty, so the rest of the family packed overnight bags and piled into the car, dropping him off at his station 4 miles away. Kim and the kids took shelter in her office at the nearby California Institute of Technology, where she now works as a safety engineer. Having lived through fires before, they all expected to be home the next morning. But at nearly 80 miles per hour, the wind speeds were beyond anything Chien had witnessed in two decades of fighting blazes in Southern California. The Santa Ana winds were crashing over the mountains like tidal waves, flinging embers far from the main fire and igniting homes in the heart of densely built neighborhoods that, after eight months of no rain, were as dry as the mountain chaparral.  The Yus' sons, Atticus and Hudson, with homemade knit toys they took with them as they evacuated during the Eaton Fire. Photographer: Stella Kalinina for Bloomberg Businessweek As Chien steered his fire engine up and down smoked-out streets, looking for people to evacuate, it was overwhelmingly clear that he and his colleagues were outmatched. Around midnight he and a crewmate drove down Highview, where through the hail of ash and fire, Chien glimpsed his own home, still intact. But the sight of a burning mulch pile on a nearby block felt like a terrifying omen. "Every time the wind gusts would come, it would just blow a ton of embers," he says. "I was just so angry at that mulch pile." By morning, along with some 9,000 other structures in Altadena, 21 of the 28 homes on the Yus' block were in ruins, including their own. What remained were the outlines of a once-intimate street: a few shared walls and all the kissing driveways. Since then the Yus have been staying in a friend's guesthouse in nearby Highland Park, trying to put their lives back together. As they work through the insurance claims process and await financial relief from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Kim and Chien are determined to rebuild, even if they're unsure how they'll afford to. They want a new house engineered up to California's modern fire codes, with flame-resistant materials and defensible landscaping. With a number of their Highview neighbors, they're drafting plans to remake their block according to Ain's original vision for a colony of homes built collectively, efficiently and—most important—affordably.  Ain's Altadena housing development in 1947. Photographer: Julius Shulman/J. Paul Getty Trust/Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Part of the goal is to restore a piece of Los Angeles' architectural history. But mainly it's to get everyone home as quickly as possible. Over the past couple of months, California leaders have signaled the same desire. Even before the fires were put out, Governor Gavin Newsom signed an order waiving environmental permitting requirements for resurrecting burned homes and businesses. Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass suspended the city's discretionary review process for rebuilding structures as they were. LA County, the main local government for unincorporated Altadena, has announced it will fast-track permits for "like for like" construction, and its elected officials have asked the state to suspend a raft of housing laws they say will slow the process. By placing so much emphasis on re-creating individual properties, however, leaders may be missing the most dramatic chance yet to examine LA's place in an ever more flammable world. The rising risk of catastrophic fire isn't a problem homeowners can solve in isolation, says Stephen Pyne, a professor emeritus at Arizona State University who's written dozens of books about the history of fires around the globe. Unlike with floods, hurricanes and other climate-driven disasters, in a fire the survival of one structure is often determined by the hardiness of its neighbor. Rebuilding the same homes in the same places could re-create the same risks that made January's fires so explosive. Pyne says the yearly blazes that sweep through Southern California's aridifying landscape call for a new approach that doesn't doom residents to endless cycles of destruction. "It's the same question we have about school shootings," he says. "How many of these does it take?" Keep reading: LA Fire Victims Are Betting on a Radical Idea to Help Them Rebuild |

No comments:

Post a Comment