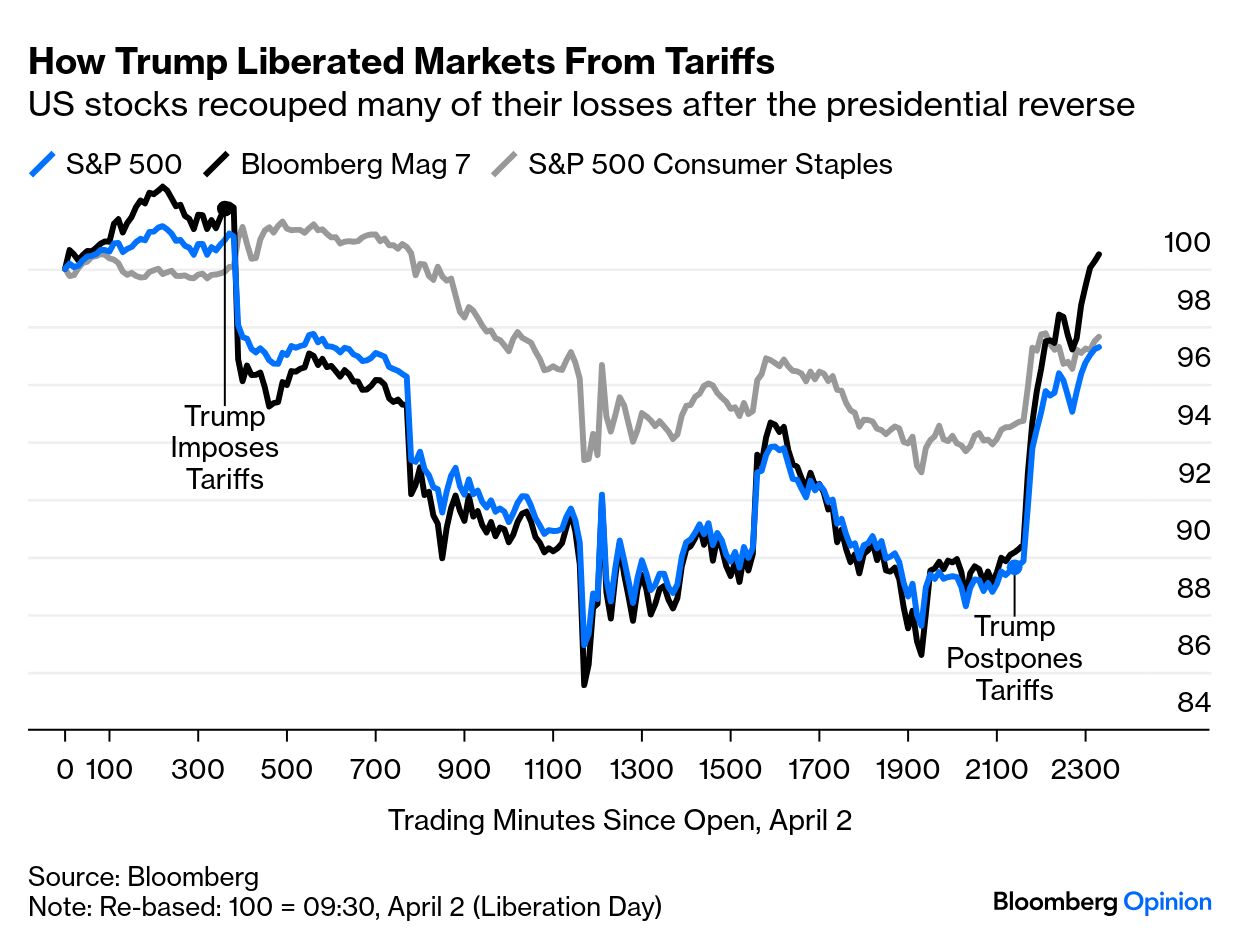

| A trade war is no game, but some participants treat it like one, and economists use game theory to analyze it. There are multiple games being played at present. However, the most famous examples from economic literature don't necessarily help. The best known are the Prisoner's Dilemma — in which the incentives on two suspects being questioned in different rooms are such that it pays both of them to snitch on the other, even though they would be better off by coordinating to stay silent — and the Chicken Game, named after a scene in Rebel Without a Cause, in which two competitors drive toward the edge of a cliff, and the loser is whoever swerves first. In the first, you need better coordination and information; in the second, pre-commitment to convince your opponent you won't swerve. The current situation has elements of both. But the Trump games with China and the rest of the world are different. The US has differing objectives. With China — on which Trump is now proposing a 125% tariff —it's locked in some kind of a battle for sharing the world. Jean Ergas of Tigress Financial Partners argues that Europe is different, as the concessions demanded have to do with perceived historical injustices, not current trade practices. "Whatever the EU does, it will never be enough. They are paying reparations — it's not about debt," Ergas said. Instead, a deal might come in the form of buying US liquid natural gas or weapons, or going easy on US tech groups.  James Dean, Natalie Wood and conflicting commitments. Source: United Archives/Hulton Archive/Getty For the China conflict, both sides have their foot on the accelerator. The Chicken Game is useful. It's also a handy way to model Trump's contest with the Federal Reserve and Chair Jerome Powell, and the markets. Will bond yields keep rising and the Fed refuse to cut rates? Nouriel Roubini made this argument to former Points of Return colleague Isabelle Lee before the presidential climbdown: There is a game of chicken between the Trump put and the Powell put. But I would say that the strike price for the Powell put is going to be lower than the strike price for the Trump put, meaning Powell is going to wait until it's Trump who blinks. There's also a Xi put, meaning at some point Xi decides to give a break to the US, but I don't think Xi Jinping is willing to do it anytime soon because that will lead to a market relief and put less pressure on Trump.

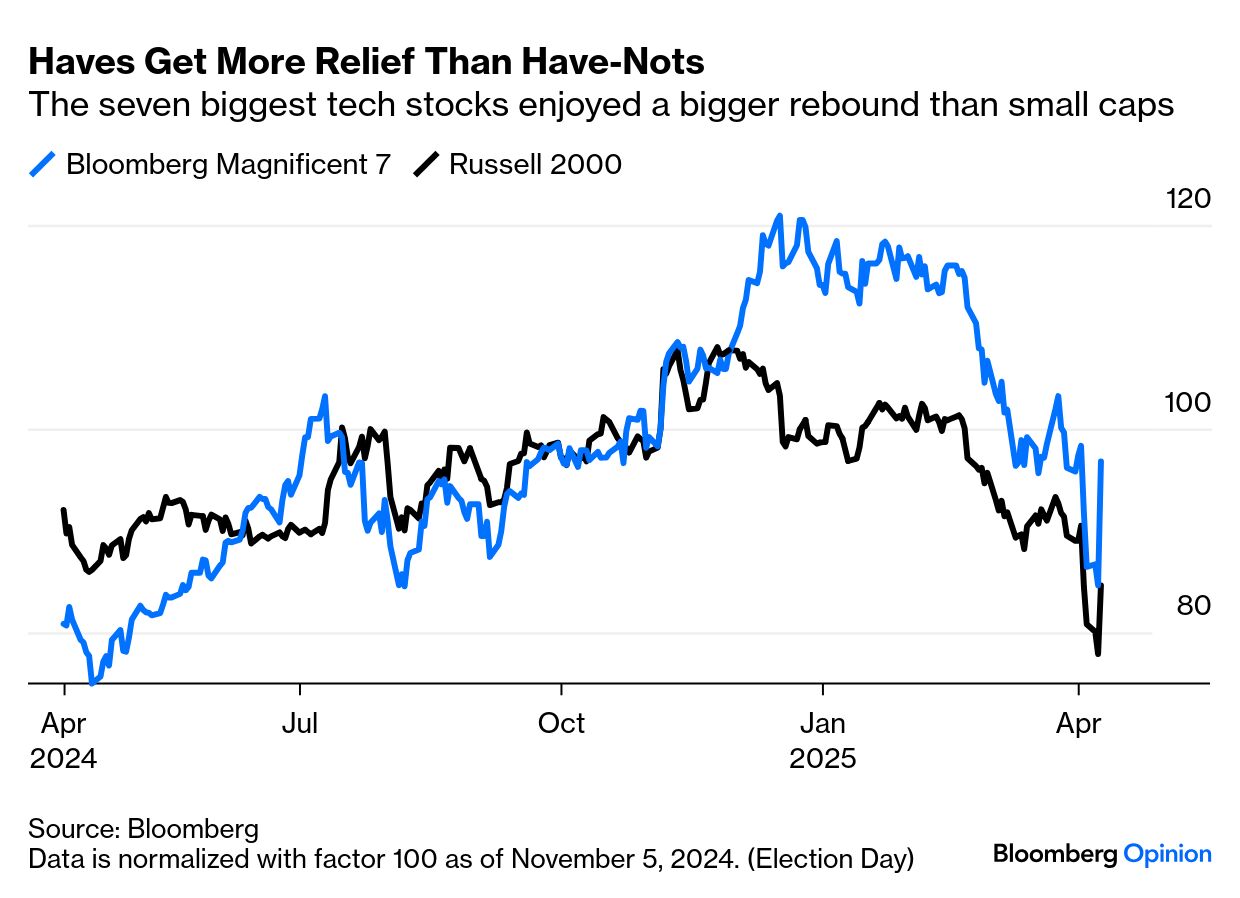

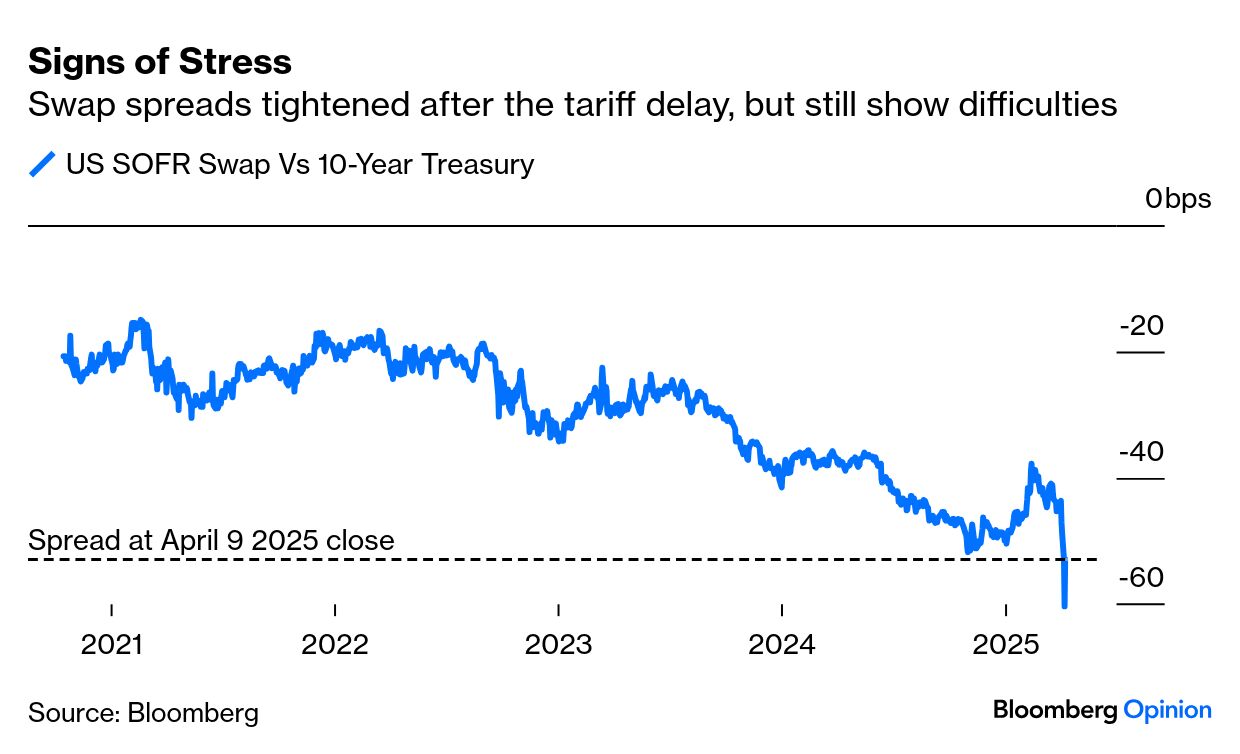

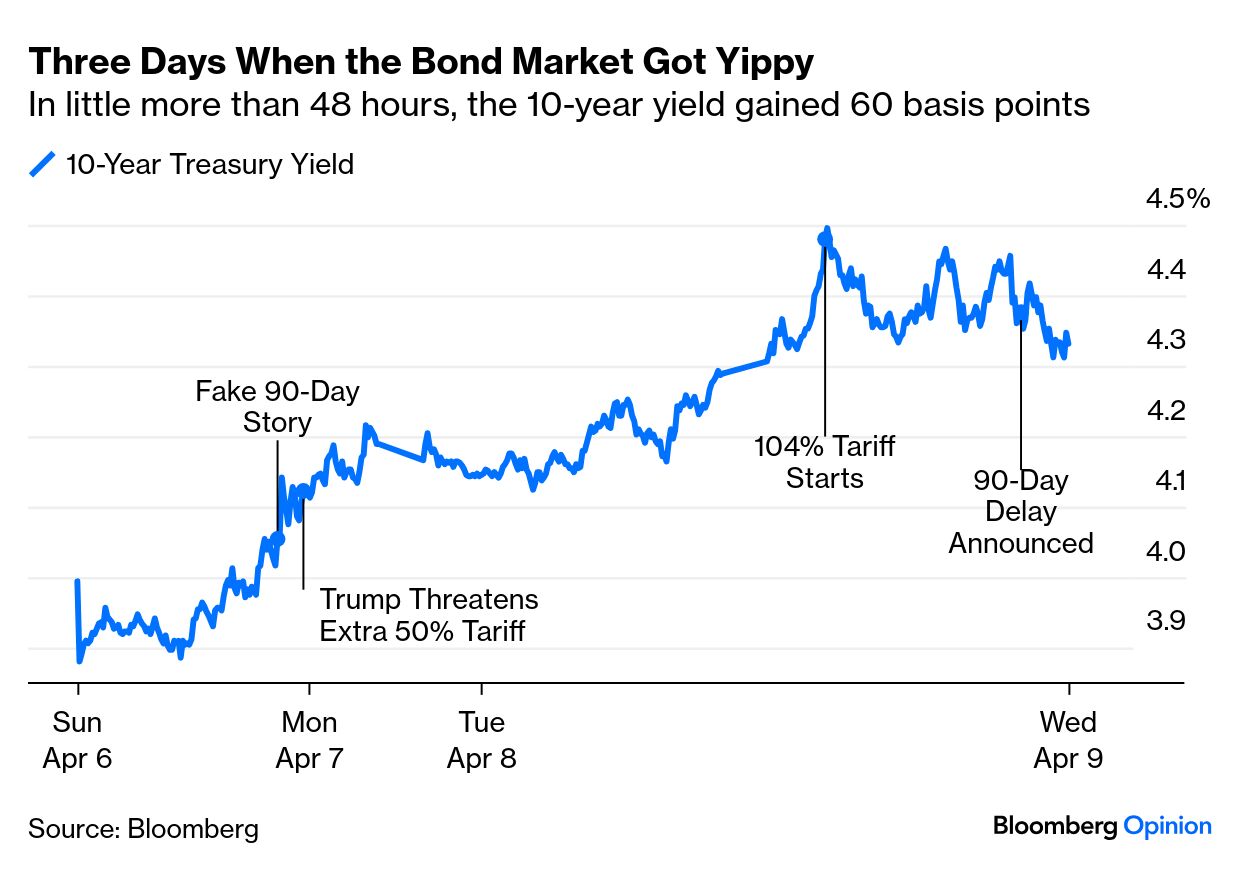

Roubini appears to be right about this. On Wednesday, the president denied that his pause was to placate a bond market that had been "yippy." But the mere fact that he raised it sent a signal to investors. George Saravelos, head of FX research at Deutsche Bank AG, said that Trump was "finally signaling responsiveness": At the margin, this should reduce the probability that such an extreme policy mix returns. It is more likely that the administration accepts negotiated outcomes on trade (and other) policies, and it is more likely the administration becomes responsive to market pressure, if this continues.

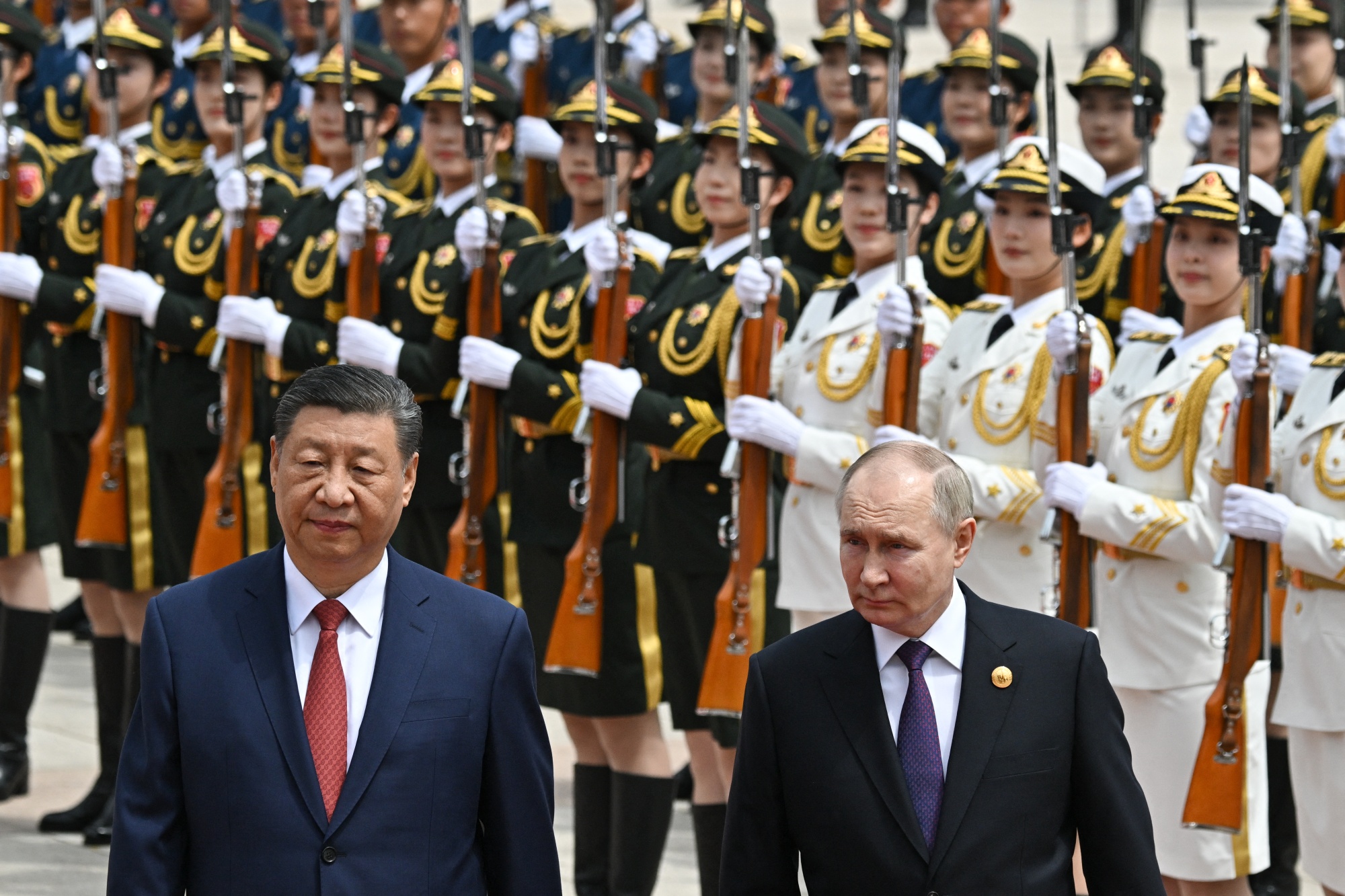

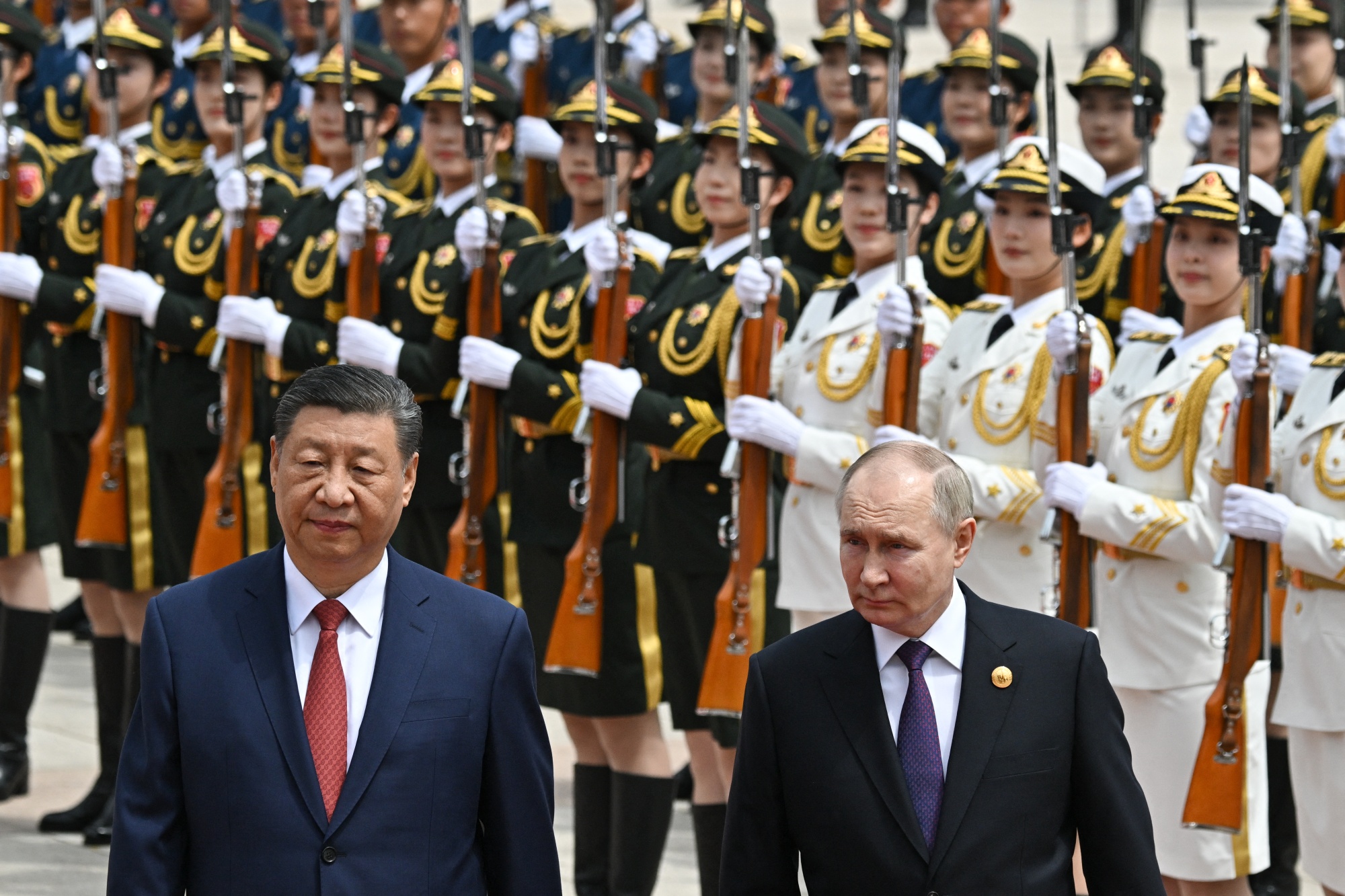

As far as the market is concerned, Trump has already blinked. Will China do the same? Wendong Zhang, an economics professor at Cornell, argues that this is a game in which China has vowed to "fight to the end" and can't be expected to back down first, even if it suffers higher economic costs than the long-term 2.5% loss in gross domestic product he projects for the the US. "The international political economy calculations mean that they are likely stick to their guns."  No one wants to look weak. Photographer: Sergei Bobylyov/AFP/Getty Like a young James Dean, the Chinese leadership really doesn't want to look weak. Or in game theoretic terms, there's a disconnect between the potential political payoffs and economic costs. To commit itself, as competitors in a chicken game must, Beijing has already reduced reliance on US agricultural products such as soybeans. For everyone else, the US is driving straight into a flock of chickens that were minding their own business. A better analogy is with bullying. Donald Trump is a bully. If you don't recognize that, the chances are that you had a better time at school than I did. Bullying can be an effective, if morally questionable, way to get what you want. And as Viktor Shvets of Macquarie points out, smaller nations are natural targets: Small nations have no bargaining power, are unable to run balanced trade with the US, and will settle. Also, several larger nations (e.g. Korea, Japan, UK, India) have numerous trade and defense relations that should enable agreements to be struck. But, it is different for Canada (existential threat), EU and China.

Can Canada or the EU be bullied into submission? The good news is that game theorists have found strategies for dealing with bullies. The problem is that to get the bully to desist, everyone must be worse off — it's just that the bully loses more. And friends have to stick by the bullied. For a beautiful explanation, try these videos by the game theorist Ashley Hodgson. For a simpler explanation tailored to the moment, try this video that I recorded before Trump's Truth post, which features Regina George, from the movie Mean Girls, standing in for Trump. Technically, "extortionists" or bullies control their victims by becoming less and less cooperative — though just cooperative enough to keep the other party engaged — and by never being the first to concede. Theoretically, they will always outperform their opponent by demanding and receiving a larger share of what's at stake.  Those rules aren't real. Source: CBS Photo Archive/Getty But a paper from Dartmouth University uses mathematical models to uncover an Achilles heel by using an "unbending strategy." When the bullied resist being the first to yield, the bully loses more. This leads to a more equitable outcome as the "overbearing party compromises in a scramble to get the best payoff." The problem is that the bullied also must be prepared to take a loss. Xingru Chen, first author of the paper, argued: "Unbending players who choose not to be extorted can resist by refusing to fully cooperate. They also give up part of their own payoff, but the extortioner loses even more." The bad news is that it pays the rest of the world to take some hits, which could make what lies ahead even more brutal. Zhang of Cornell argues that China has already primed citizens to treat what's coming stoically and take some pain, while media are full of accounts of how badly the trade war will hurt the US. "So the perceived tolerance level for losses could be higher." Exports are a much smaller share of the US economy than for many of its adversaries in this conflict. But Americans now have to pay tariffs on all goods coming in, while other countries have to worry only about what they get from America. In the long run, logically, this means even more pain for the US. It has little to gain in trade terms from smaller countries that don't currently charge it high tariffs. Thus, if other countries stick together, game theorists suggest that the bully can be beaten. Rationally, this may well be their best strategy — but it comes at great cost and takes time. With universal 10% tariffs still in place, and a possible return to more punitive rates in three months, it's best to assume that this conflict will grind on for a long time yet. |

No comments:

Post a Comment