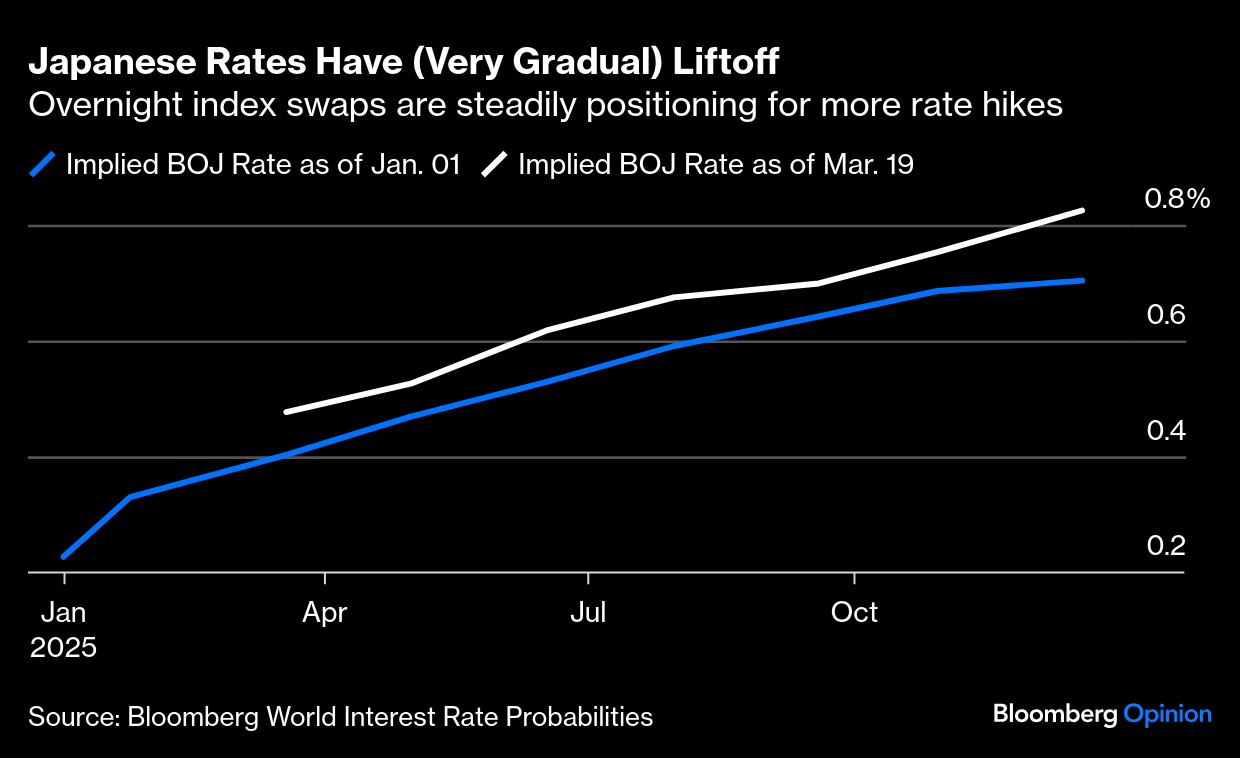

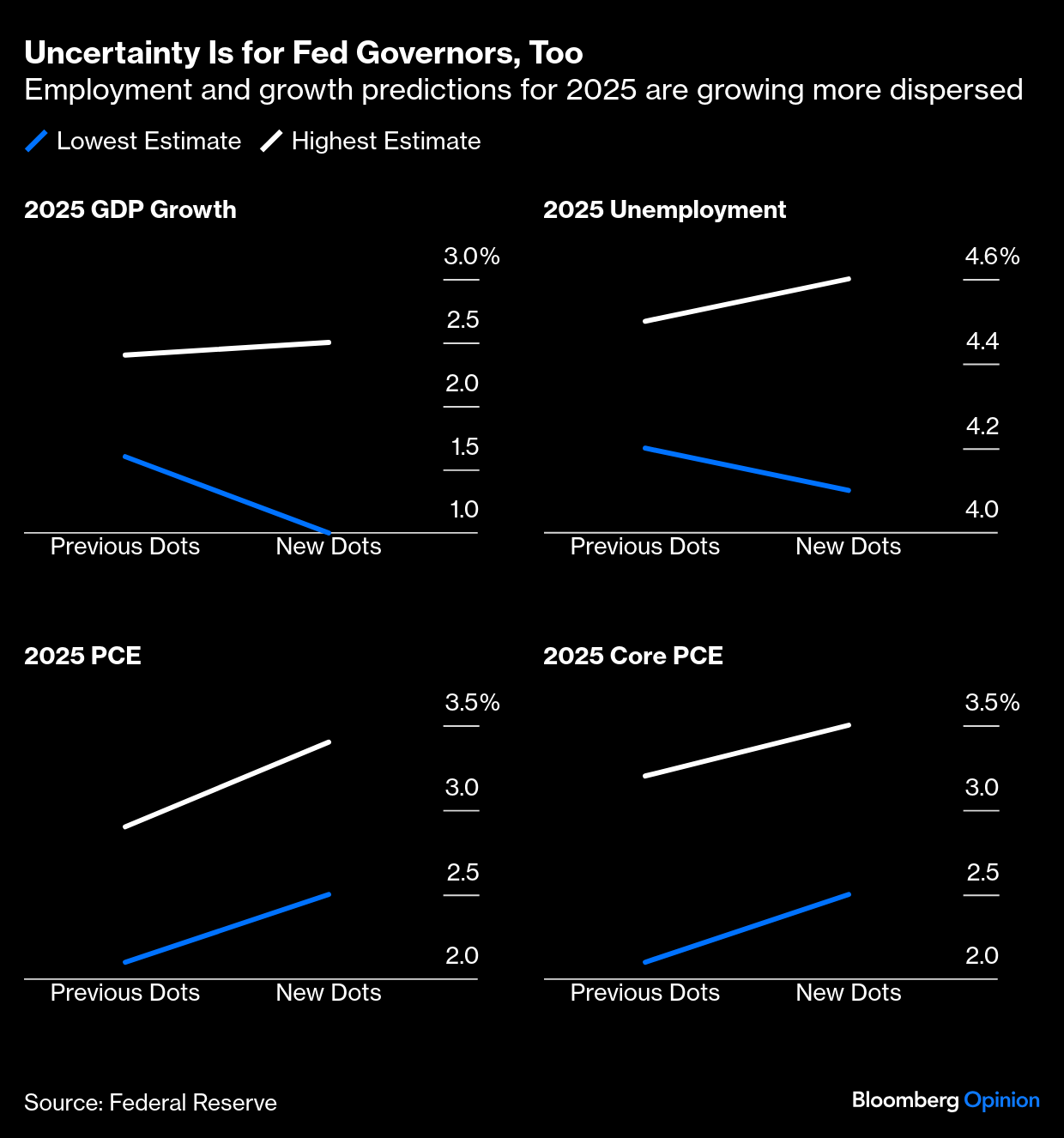

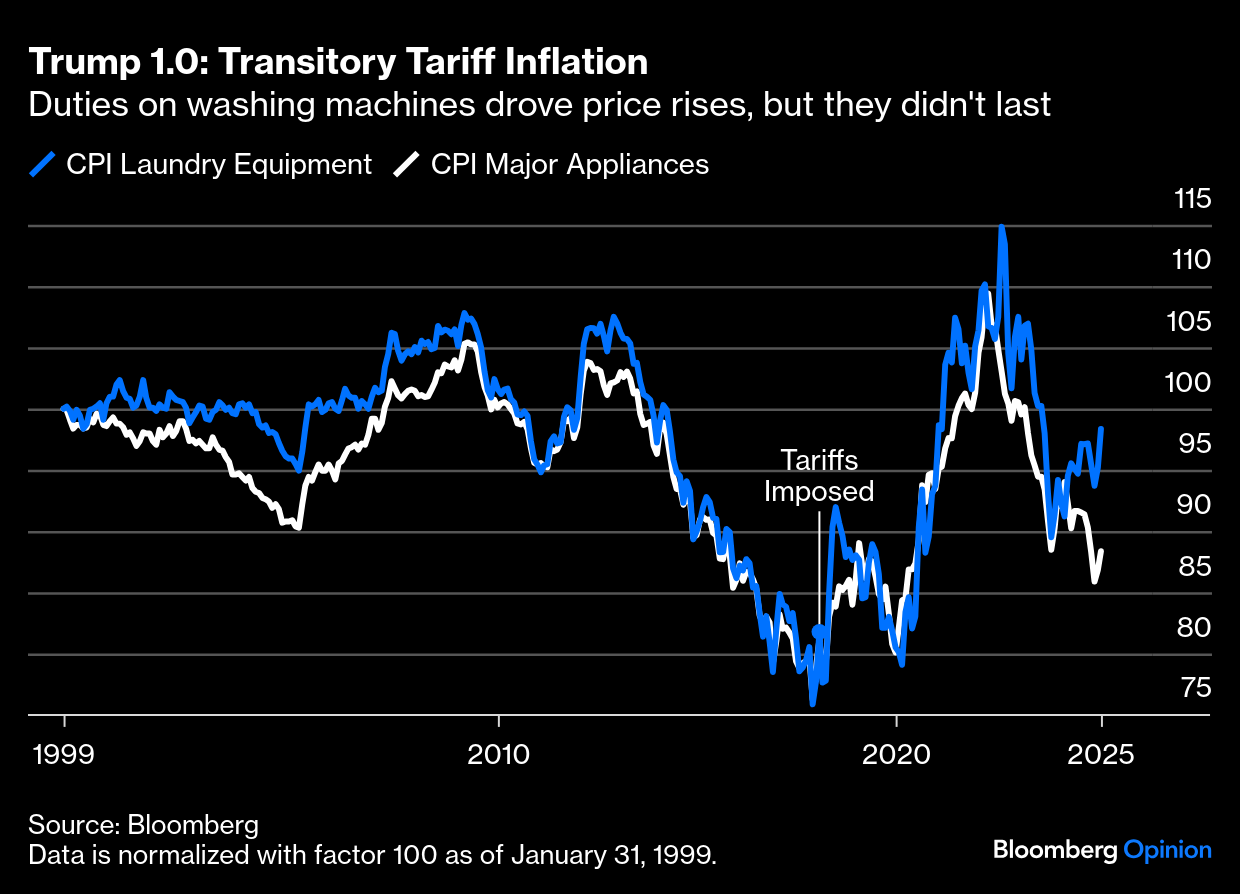

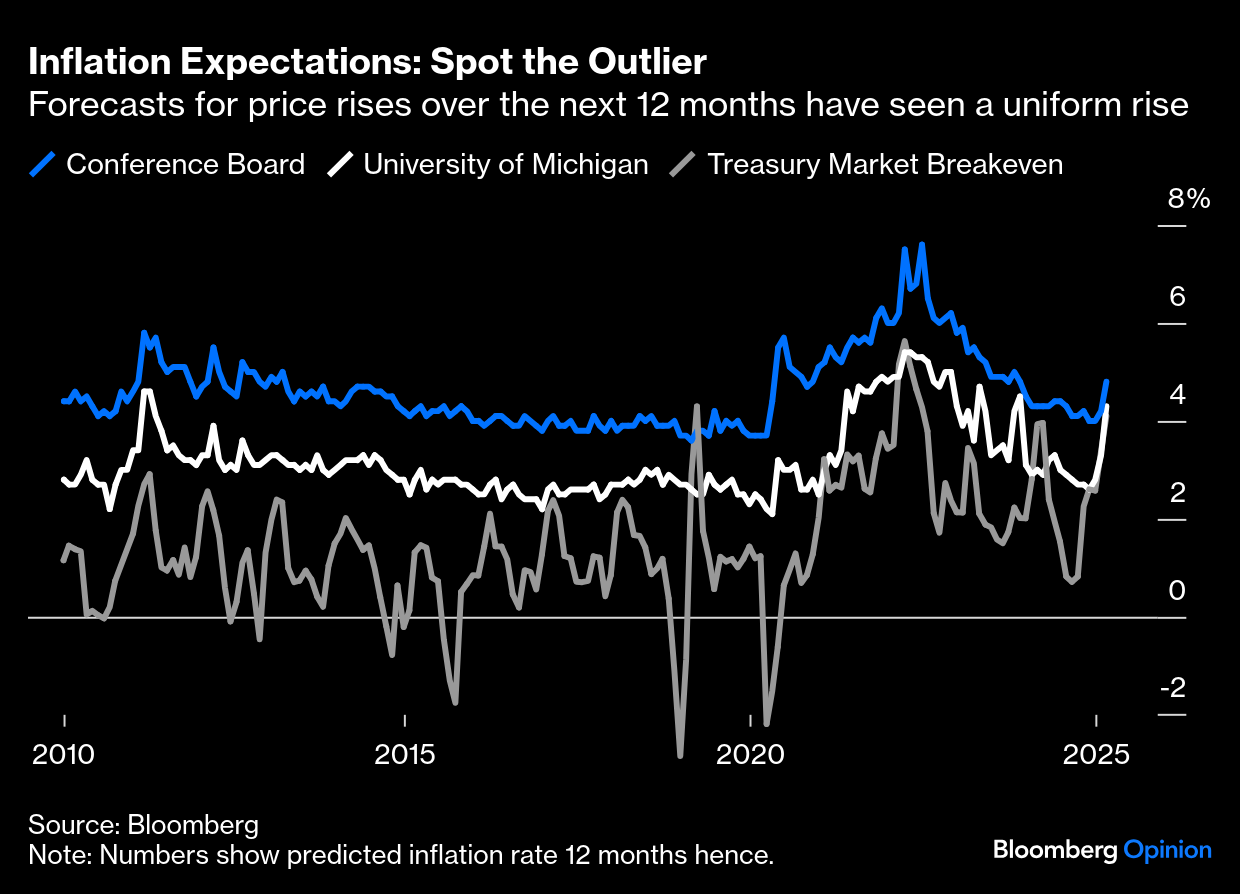

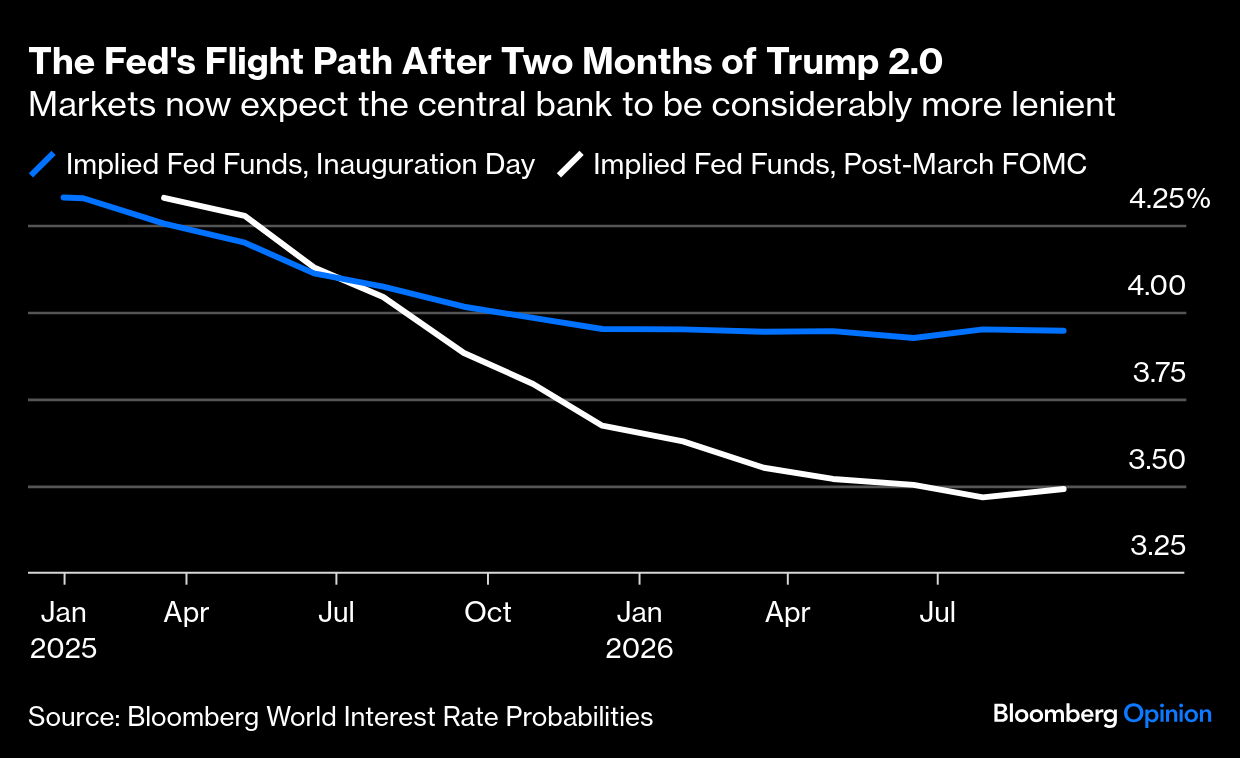

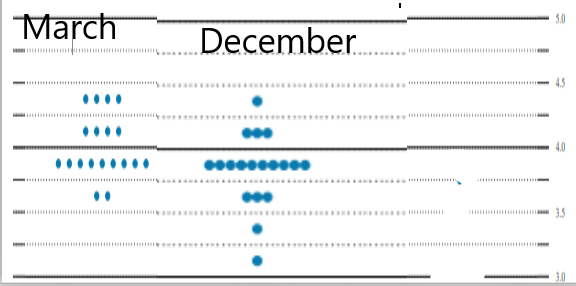

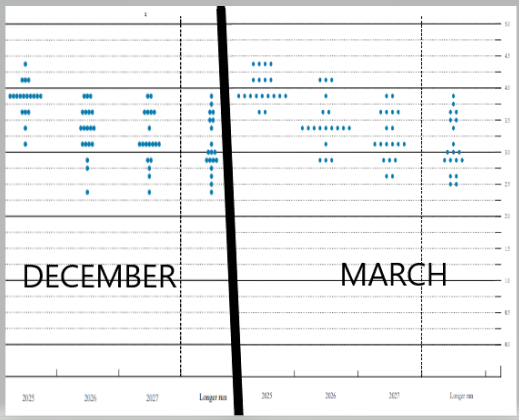

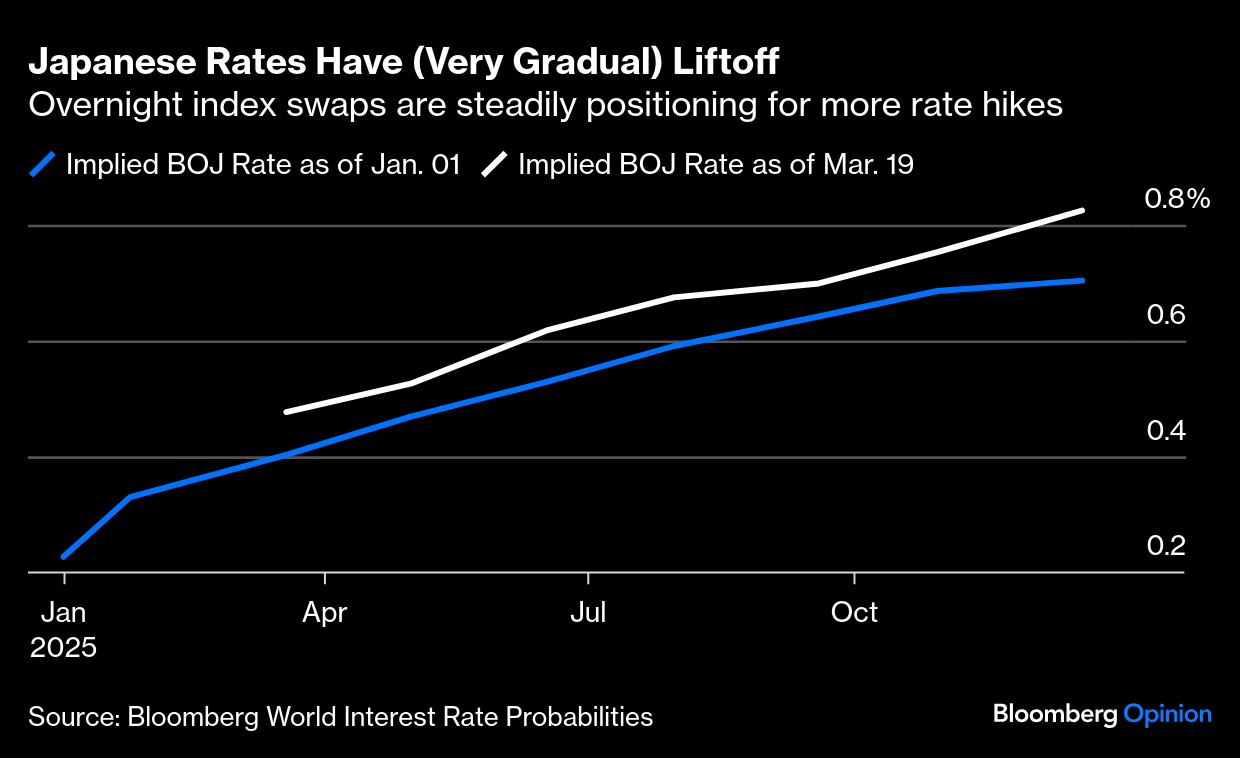

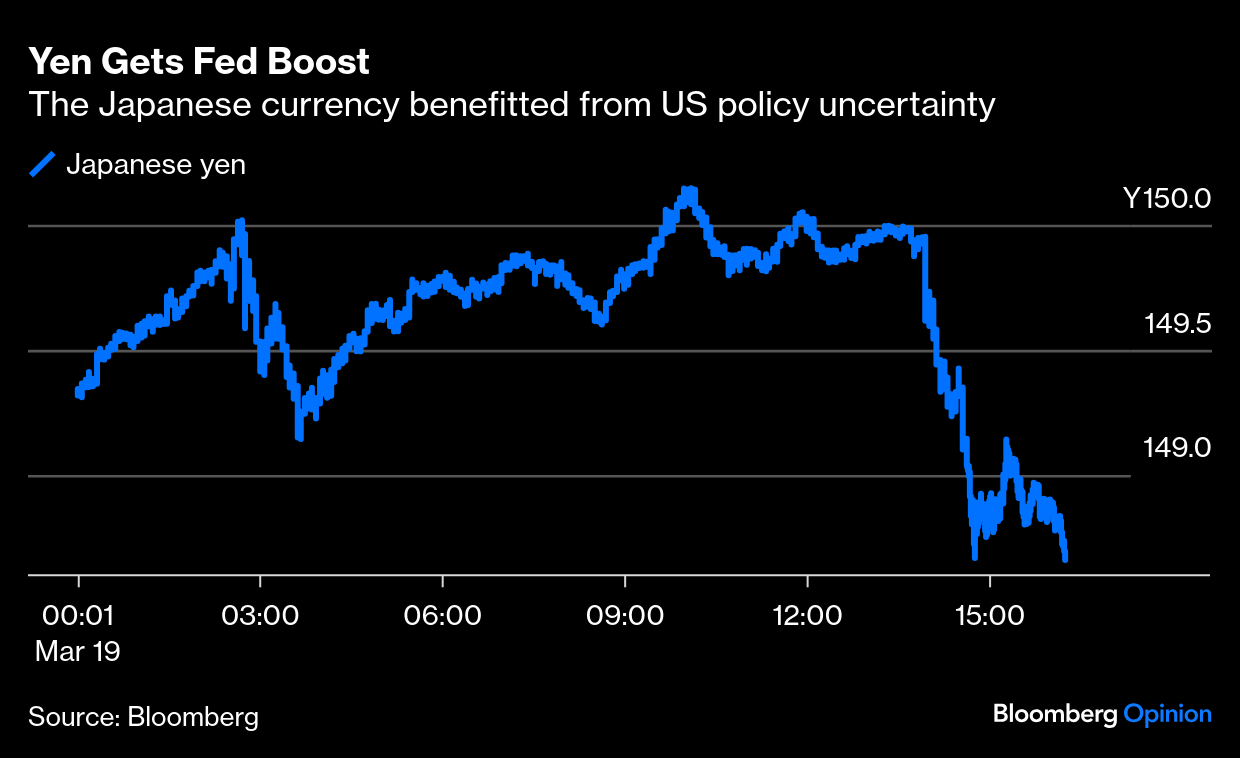

The Fed Doesn't Have a Clue, Either | "Never be embarrassed to admit ignorance," I was told on my first day of work as a journalist. "It's the first rule of journalism." I've never forgotten that, and the same applies to central bankers, as the Federal Reserve's Jerome Powell made clear when he repeatedly told the press that he didn't know what was going to happen with US trade policy, or what effect it would have on the economy. The Federal Open Market Committee left the fed funds rate unchanged, as universally expected, and caused a bit of a surprise by tinkering with the quantitative tightening regime for reducing the size of its balance sheet by selling bonds. That's a move toward easier money, although Powell explained it as a technical maneuver to guard against sucking up too much liquidity in the bond markets. A notable if bland new sentence entered the always-understated communique: "Uncertainty around the economic outlook has increased." That, Powell made clear, is due to the confusion surrounding the new administration, particularly over tariffs. The FOMC also showed that uncertainty graphically with the members' latest dot-plot economic forecasts. Three months into 2025, the likely outcome for the year should be clearer than it was when the committee last published estimates in December. But their guesses on growth and unemployment grew more scattered and inflation forecasts rose: On the face of it, growing uncertainty, higher inflation expectations, and falling growth are pretty horrible. It adds up to a measure of stagflation. Yet markets reacted as if Powell had steered them toward more rate cuts. A surge in stocks greeted the initial announcement, while bond yields adjusted lower. Those moves gained momentum during Powell's Q&A, although the stock market later gave up some gains: Why? Any move to relax QT is welcome, and Powell has been interpreted as saying that the Fed wouldn't hike if tariffs drove a rise in inflation. He even used the fateful word "transitory" to describe what happened after Trump 1.0's tariffs. At the beginning of 2018, the administration imposed a levy on imports of washing machines, whose price had been declining for years. Tariffs turned that around. This is the official CPI data: Powell perhaps unwisely rose to reporters' bait and described the resulting inflation as "transitory," but that does appear to be accurate for what happened on this specific occasion. After a while, prices fell again. If that experience repeats itself on a larger scale in the months ahead, the Fed would be right to hold off on raising rates. Markets also liked his response to a question about the sharp rise in consumer inflation expectations recently flagged by the University of Michigan's regular survey, which he dismissed as an "outlier." That implies A) that the Fed isn't too worried about rising inflation expectations yet, and B) that they haven't been looking at all the available surveys: Whether this was willful denial or a belief that tariffs are confusing the issue so much that surveys can't be trusted, it bolstered the market's growing confidence that the Fed will cut rates at least twice this year — probably three times. The implicit path for fed funds predicted by the futures market (according to Bloomberg's trusty World Interest Rate Probabilities function) has shifted significantly since Trump's inauguration: But now we come to the tricky part. It's not clear to me that this FOMC was dovish. Powell seemed to be giving himself maximum room for maneuver, which was wise. Meanwhile, the dot plot, in which each committee member predicts the future course of the fed funds rate, shows a Fed losing confidence in cuts. Using my customary lo-fi approach of cutting and pasting from the press release using Paint, this is how the projections changed between December and March for interest rates at the end of this year:  It's customary to summarize the dots using the median, which is unchanged. There's a big bunch of FOMC members who expect to cut to between 3.75% and 4%, just as there was last time. That means two 25-basis-point cuts this year. But the number who expect to cut further has dropped to two from five, while those expecting only one cut or none has doubled from four to eight. The mean expected end-2025 rate has risen from 3.63% to 4.0%. Effectively, that's 1½ cuts that the governors now think they won't make — even as the market still pencils in 3.63%. In this case, the mean seems plainly more useful than the median. The committee still expects to cut twice, but the risks have emphatically moved to cutting less rather than more. For one more lo-fi rendition, here are December and March's full dots from here to 2027 and beyond. The flight path hasn't changed much, but is shallower now: These central bankers are honestly admitting to rising uncertainty and risks of stagflation, while implicitly promising to try not to break the economy. It's hard to see this as a significant turning point that should bring people into risk assets. One final point for the administration: Tariffs may be a useful tool in negotiations, but threats aren't costless. Amping up the uncertainty has the real-world consequence of deterring people from taking risks. There are limits to how far trade policy can continue to be conducted this way.  | | | Presiding over monetary policy has more in common with piloting a plane than many would realize. With Powell at the controls, the Fed navigated high interest rates without crashing the economy as initially feared. The Bank of Japan's Kazuo Ueda is captaining a rates takeoff. Last year's exit from negative policy has been smooth, barring air pockets of wild currency swings. The BOJ left rates unchanged this week, and the lack of urgency for a faster climb makes sense. An aircraft making a sudden sharp ascent risks many problems, which justifies Ueda's cautious approach. Increases in the annual wage negotiations or shunto, combined with rising food prices, suggest that the next hike is only a matter of time. Rates are now projected to climb a bit faster than they were at the turn of the year, according to overnight index swaps:  Like Powell, Ueda is constrained by Trump's unpredictability, while Japan's ongoing political crisis and sub-par economic recovery efforts also make life harder. Last quarter's gross domestic product was revised to 2.2% from an annualized 2.8%. Subdued growth is driven by weak consumption, even as price growth outruns an increase in wages. As Gavekal Research's Udith Sikand argues, it would be deeply ironic if policymakers were finally to declare the end of deflation, only to enter a stagflationary wage-price spiral as the shrinking working-age population rediscovers its wage-bargaining powers. But for now, the BOJ continues to exude confidence that a "virtuous cycle" is imminent in which higher wages fuel more consumption, enabling the economy to weather higher interest rates. Ueda indicated that a hike could come at the May 1 meeting. Bloomberg Economics' Taro Kimura forecasts two 25-basis-point hikes this year, taking the target rate to 1%. The current pause allows the BOJ to parse the impact of potential tariffs Trump may impose next month. Any hike would provide an additional boon of strengthening the yen, which Trump has criticized as too weak. This is how the currency moved in the aftermath of the hawkish hold and the Fed's meeting: A hike could increase currency volatility, like last summer's carry-trade unwind, but Ueda appears determined not to blindside the market again. Sikand suggests that institutional money could be repatriated if the yen rises through more key thresholds — a self-reinforcing feedback loop that could scupper the BOJ's plans to continue hiking rates, just as in last summer's mayhem it had to walk back hawkishness. The other problem with higher rates is that the country might not be able to afford the borrowing costs: At eight years, the average maturity of Japan's public debt is longer than that of most OECD economies. However, the sheer scale of Japan's debt — more than 250% of GDP — still weighs on public finances. The Ministry of Finance estimates that interest expenses will rise by 50% over the next few years to hit ¥16.1trn (US$109bn) in the fiscal year ending in March 2029.

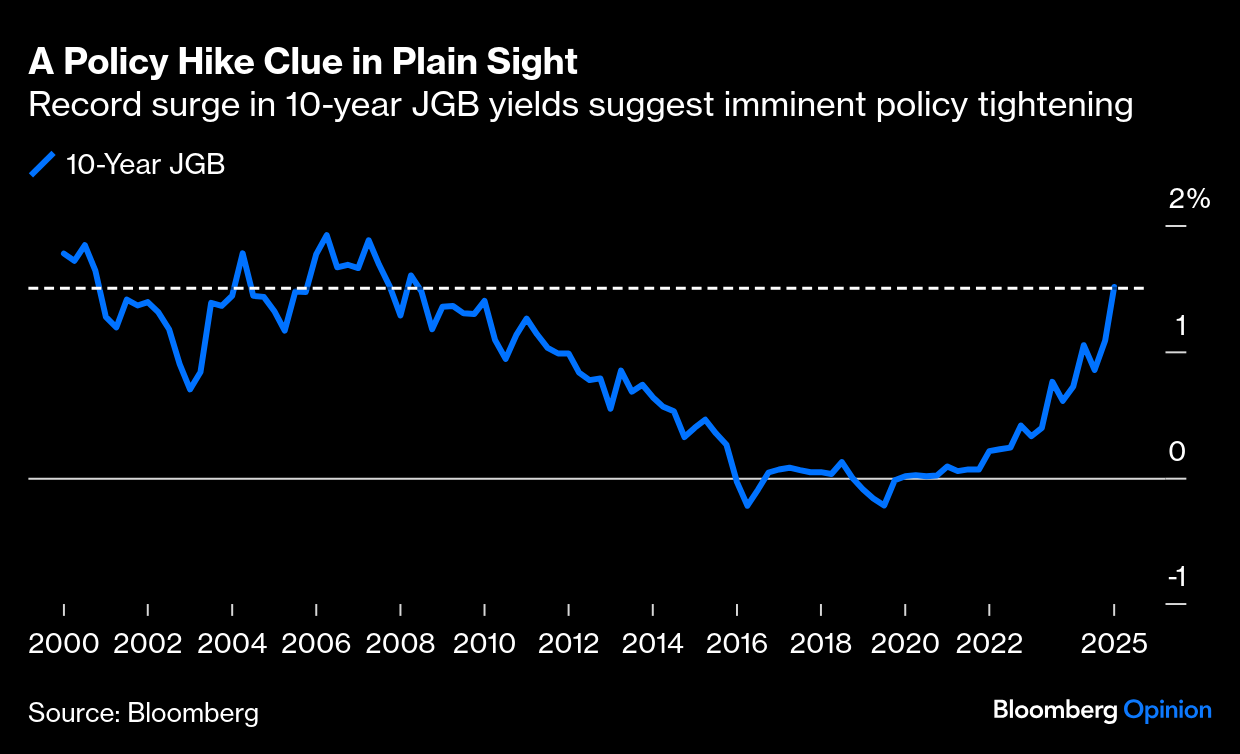

For now, the market seems confident a hike is imminent. The 10-year Japanese government bond climbed above 1.5% earlier this month, its highest in 16 years, driven by expectations of additional policy tightening over higher inflation: Central bankers will all have to navigate Trump's trade policies. Incoming data will help find a course, but tariffs exacerbate challenges relating to high rates, inflation, and currency volatility. The passengers have no option but to trust their pilots, but that's not reassuring. —Richard Abbey Points of Return Public Service Announcement | If you have a subscription to the Bloomberg terminal, thank you. Also, you should know about a new function now available to all clients. If you go to CHRT <GO> you get access to a massive database of charts that have appeared on Bloomberg, in handy sortable form. Should you wish, you can even go to the left-hand column, click on John Authers in the list of chart authors, and be presented with the last 225 charts produced for this newsletter. This is what the page looks like: And these are the filters down the left-hand side that you can use to narrow the search, or just get access to Points of Return: If you subscribe to this newsletter, the chances are that you rather like charts, so this could be for you. Enjoy. A propos of nothing, I've spent the last two hours writing up central bank analysis while listening to my favorite Arcade Fire songs on YouTube. As it's now almost exactly 10 years since Paul Krugman prompted me to start listening to them, and prompted the musical equivalent of an adolescent crush in middle age, here are my favorite live performances. I really love watching them. Try: Reflektor at London's Earls Court in 2013; Month of May on "Later with Jools Holland" in 2010; a cover of Poupée de Cire, Poupéee de Son from 2007, performed in Paris; Headlights Look Like Diamonds from 2004; No Cars Go at Coachella in 2011; Power Out and Rebellion (Lies) from Rock en Seine in 2007; Rabbit Hole at the BBC in 2022, City With No Children (which they should play far more often) from 2011; We Used to Wait, performed for MTV in 2010; coming back from the pandemic in New Orleans in 2022; and performing valiantly in a thunderstorm at Pinkpop in the Netherlands in 2013. It makes me happy; hope it has the same effect on you.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Marc Champion: Putin and Trump Take a 'Win' at Ukraine's Expense

- Stephen Carter: Roberts Was Right to Chastise Trump

- Lionel Laurent: Fighter Jet Fury Makes Macron's Planes Look Good

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment