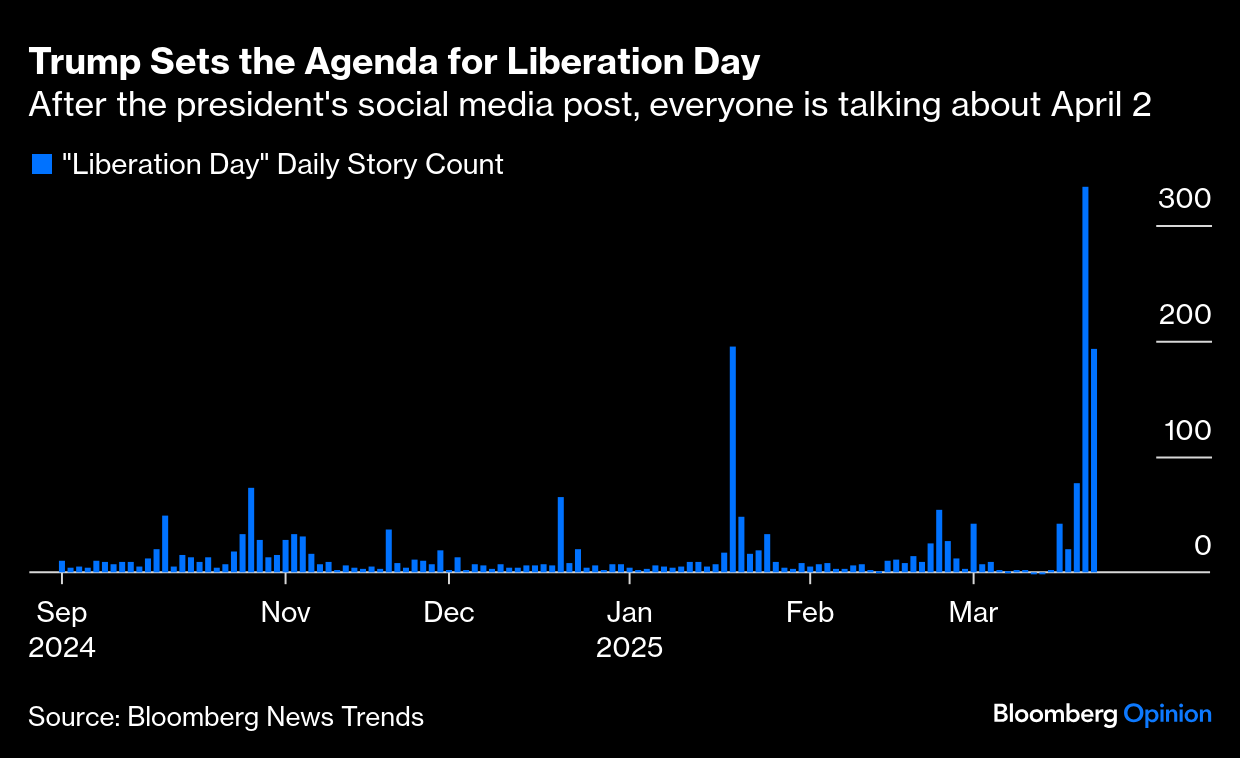

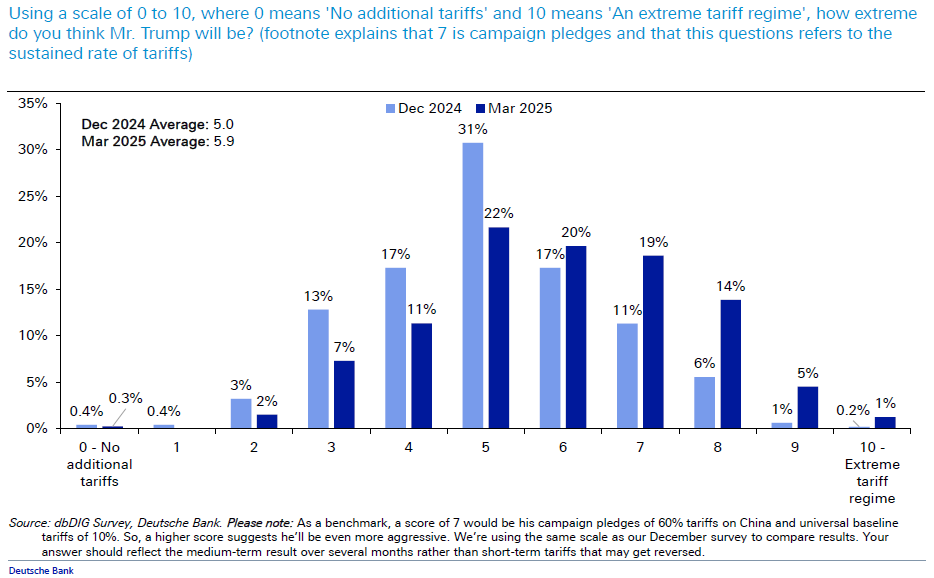

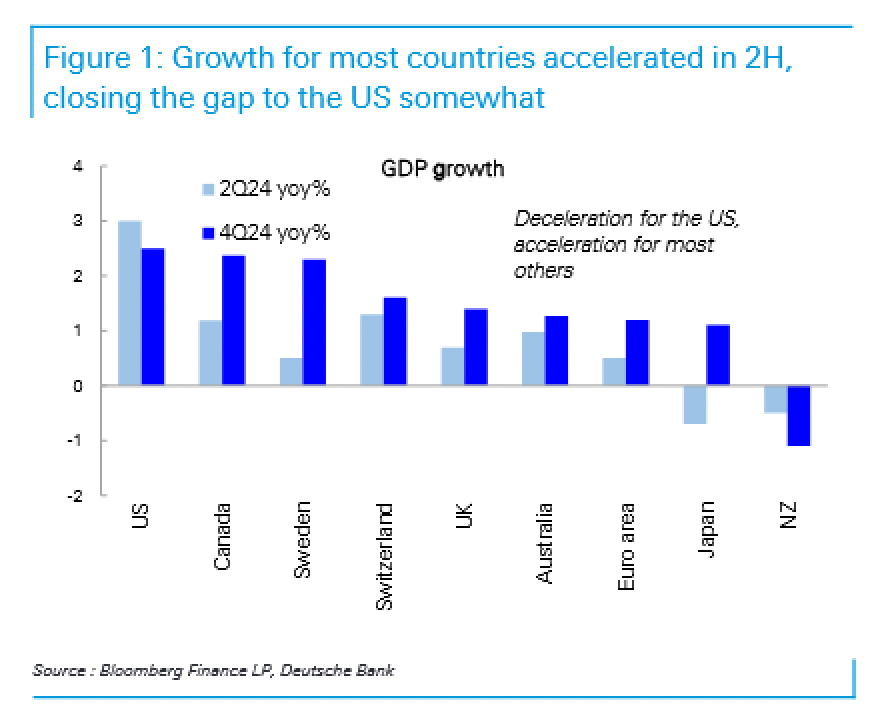

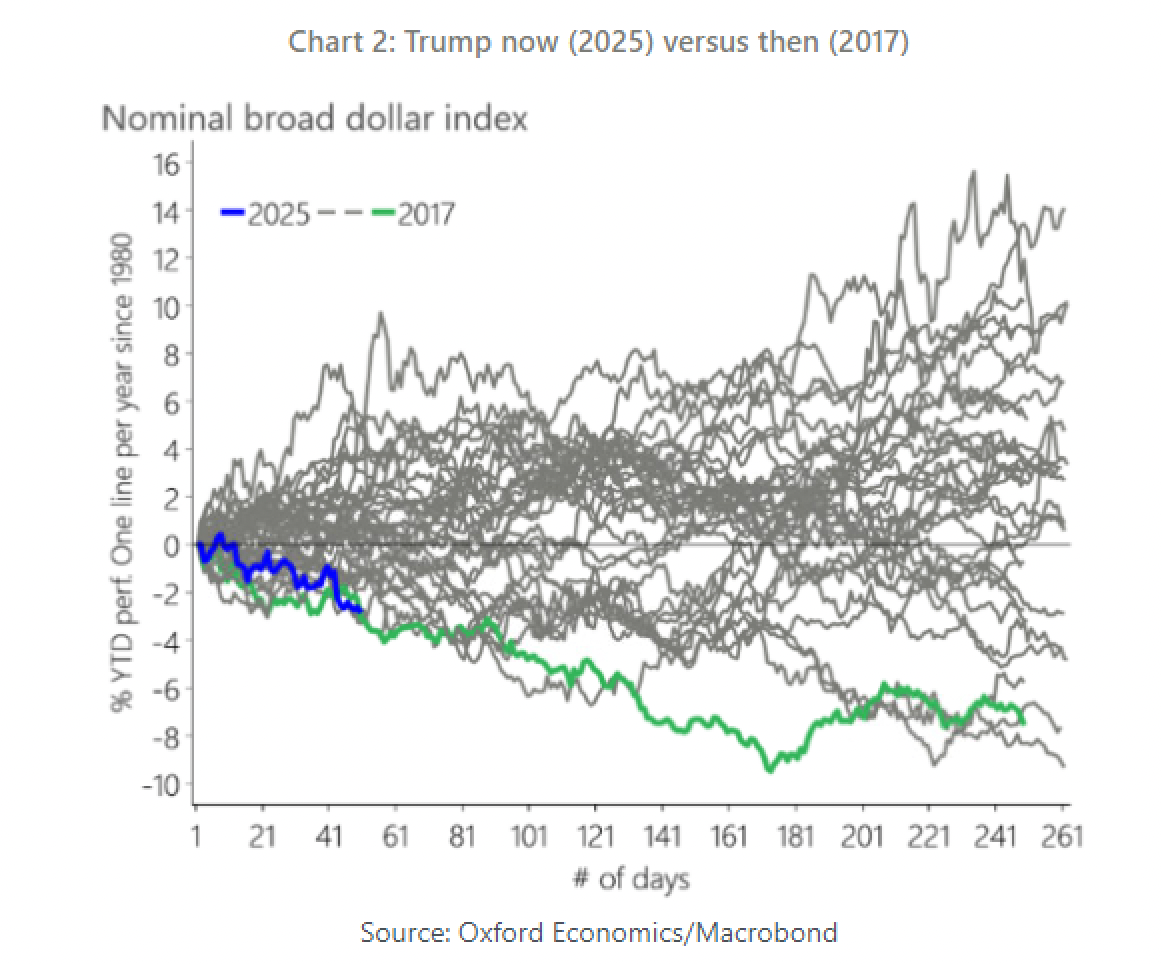

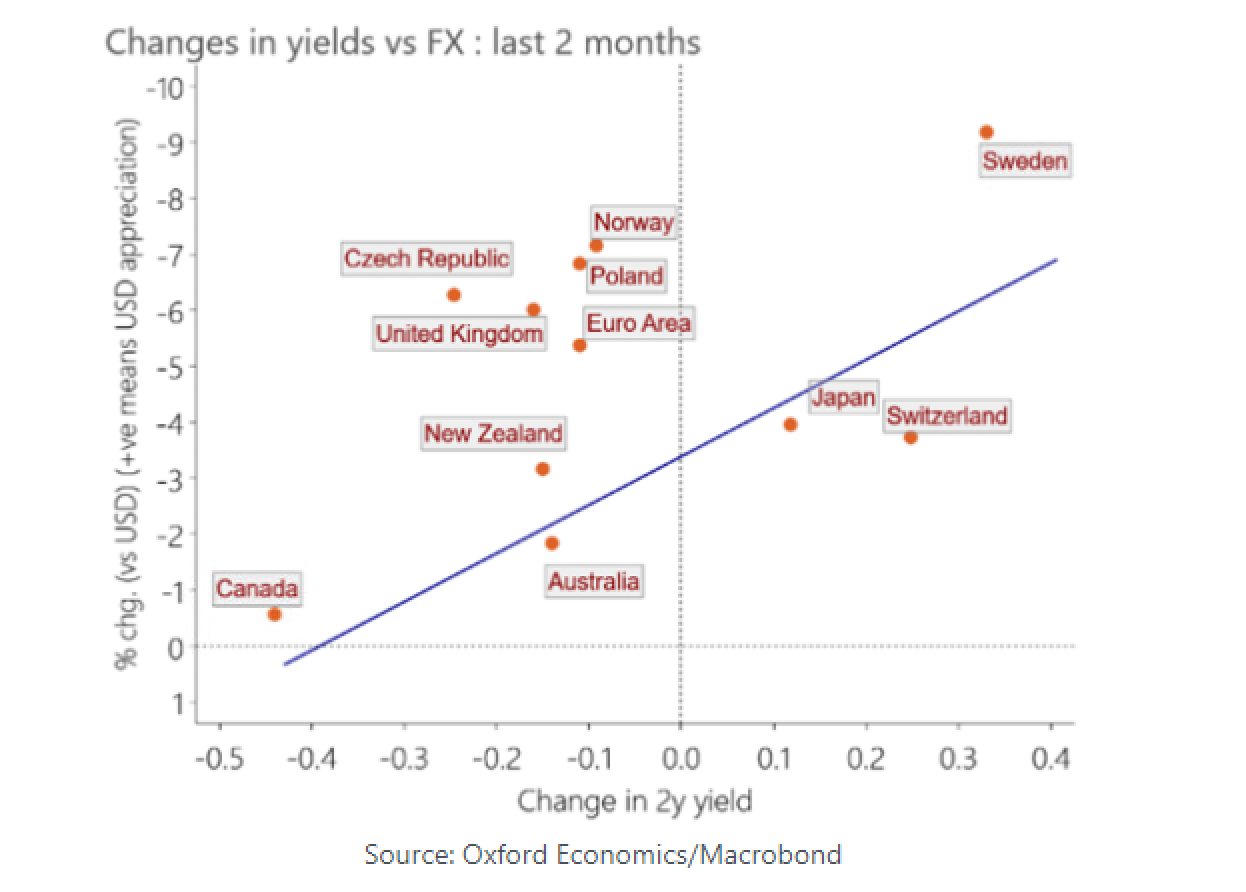

| Nobody has ever questioned Donald Trump's ability to set the agenda with a telling phrase. Suddenly, market conversation is dominated by Liberation Day, the name he's given to his announcement of reciprocal tariffs on April 2. A count of news stories from all sources on the Bloomberg terminal shows an explosion of interest: While Trump means the phrase to refer to the imminent liberation of the US from what he calls an unfair world trade order, markets expect to be liberated from the dangerous threat of heavy global tariffs. As Deutsche Bank's regular survey of traders shows, they were confident that Trump's tariff bark would be worse than his bite back in December. They're taking the threat of tariffs much more seriously now, but still think the net effect will be less severe than he trailed during the campaign (scored as a seven for the purposes of the exercise): Liberation Day, for all that Trump is building it up, could reassure investors that they had it right the first time. Bloomberg's weekend story that the administration would opt for a "targeted push" was interpreted as meaning it would retreat — even if Monday's tariff pronouncements were a little more alarming. So what exactly is the idea behind the reciprocal tariffs that will liberate us?  | | | The idea of reciprocity is simple — even "beautiful," as the president puts it. Compared to the various plans Trump has aired for blanket tariffs on particular sectors, like those in place on steel and aluminum, they are also far lighter, creating less disruption for the economy and generating much less revenue for the Treasury. Strategas Research Partners' Dan Clifton estimates sectoral tariffs are roughly twice the size of likely reciprocal tariffs. That's because, as revealed in UBS research that Points of Return covered earlier, the US is not that hard done by, and its main trading partners' tariffs are already reciprocal. In general, they're the countries with which the US already has free trade agreements. Further, reciprocity is difficult, as products can be subdivided any number of ways. Morgan Stanley's economics team comments that "to define reciprocity at a product or sector level requires excruciating details not only around product classification but also how products are treated by domestic policy." They are also further subject to override or amplification by the president after companies and countries have lobbied him. "All we care about is jobs," Trump said Monday. "We have a lot of people coming in." The administration must also convince investors and businesses alike that these tariffs won't hurt the US. "Countries that sell to the United States are inflexible. They've only got the United States to sell to," Stephen Miran — chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers — told Bloomberg TV on Monday. "So they're the ones who bear the burden of these tariffs." This is a good point, but may prove to be overstated. US trading partners are already scurrying to find alternative markets, and to rebuild their own capacity. The European attempt to rearm is only the most spectacular example. But as a broad rule, US tariffs should indeed hurt others more than they hurt the US. The dollar is exceptional under MAGA, but not in a good way, and is down by about 4% for the year. At one point, it shed all its post-election gains. Tariff uncertainty is doubtless part of this, but even before "Liberation Day," it's legitimate to question whether the weakness is overdone. As Deutsche Bank's Tim Baker points out, the services purchasing managers index or PMI has rebounded, and the apprehension begins to look overplayed. In part, it's a reaction to improved growth prospects elsewhere. This chart shows that gross domestic product accelerated in the second half of last year in most developed economies: Tariffs plainly also a play part, and the foreign exchange market loves the idea that they will be rather more targeted. That's provided some relief for the greenback, after its lowest sessions since October: Another key point is that analysts still have the first Trump term as a template. Oxford Economics' global macro strategist Javier Corominas draws parallels between the dollar's current performance and Trump 1.0. It suggests the weakness we are seeing is nothing new: But it's too simplistic to expect everything to check out and proceed on the 2017 path. That would water down the historic significance of Germany's fiscal splurge, which could add two percentage points to growth over the next four years. How much could this impact the euro? Corominas argues that Germany's fiscal sea change is already fully priced. He offers this chart to make his case:

What does the change in yields tell us? Corominas notes that the euro has overshot the relative move in yields over the last month. That may be justified, but he says the implication that the euro will strengthen further doesn't necessarily follow:

This is not a plain vanilla fiscal boost, and our experience over recent years has made us wary of the risk that projects will be delayed due to planning issues. For instance, it took until 2024 to see a big rise in defense spending in response to the war in Ukraine and the off-budget defense fund that was created in 2022. We also think that, unlike the US, Germany can run sizable fiscal deficits without causing a large inflation overshoot. This is because the economy has ample spare capacity after three years of stagnation. We think the output gap is between 1% and 2% of GDP.

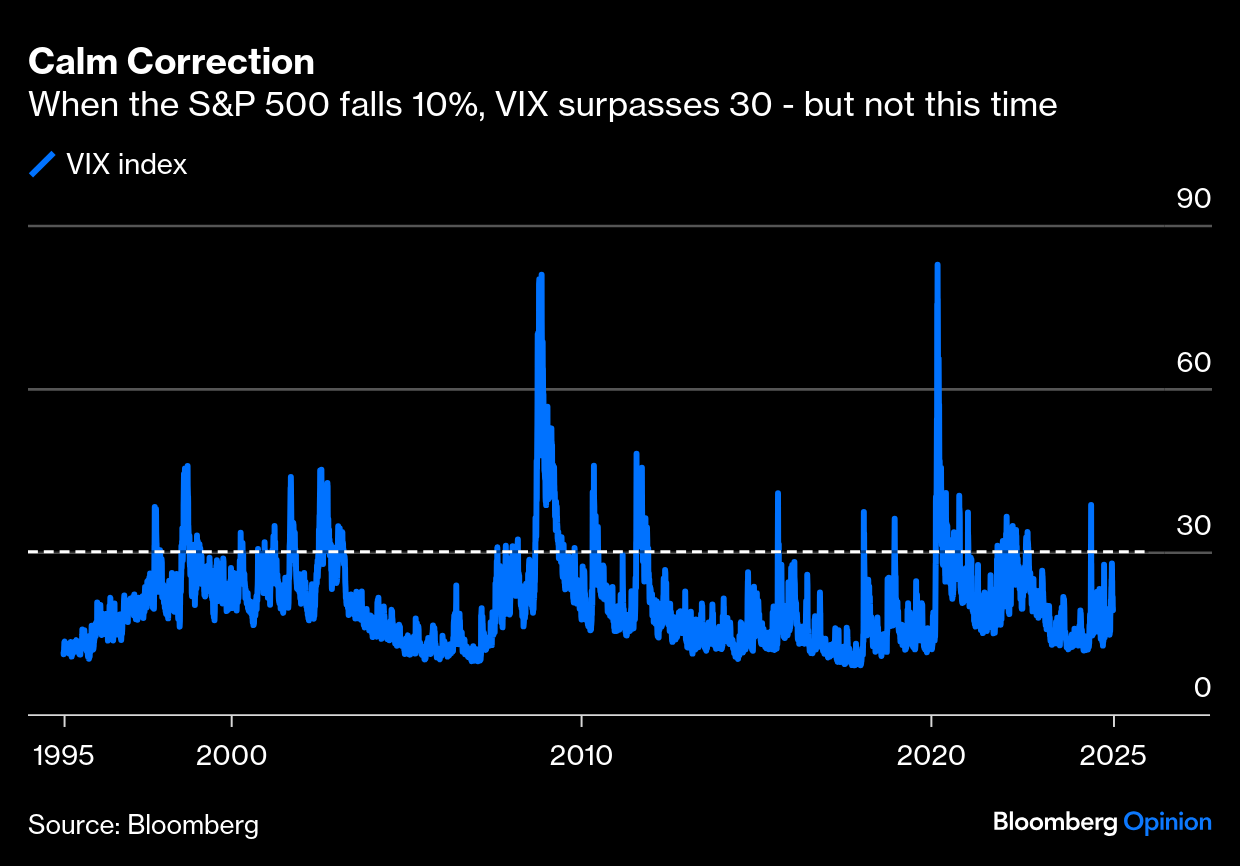

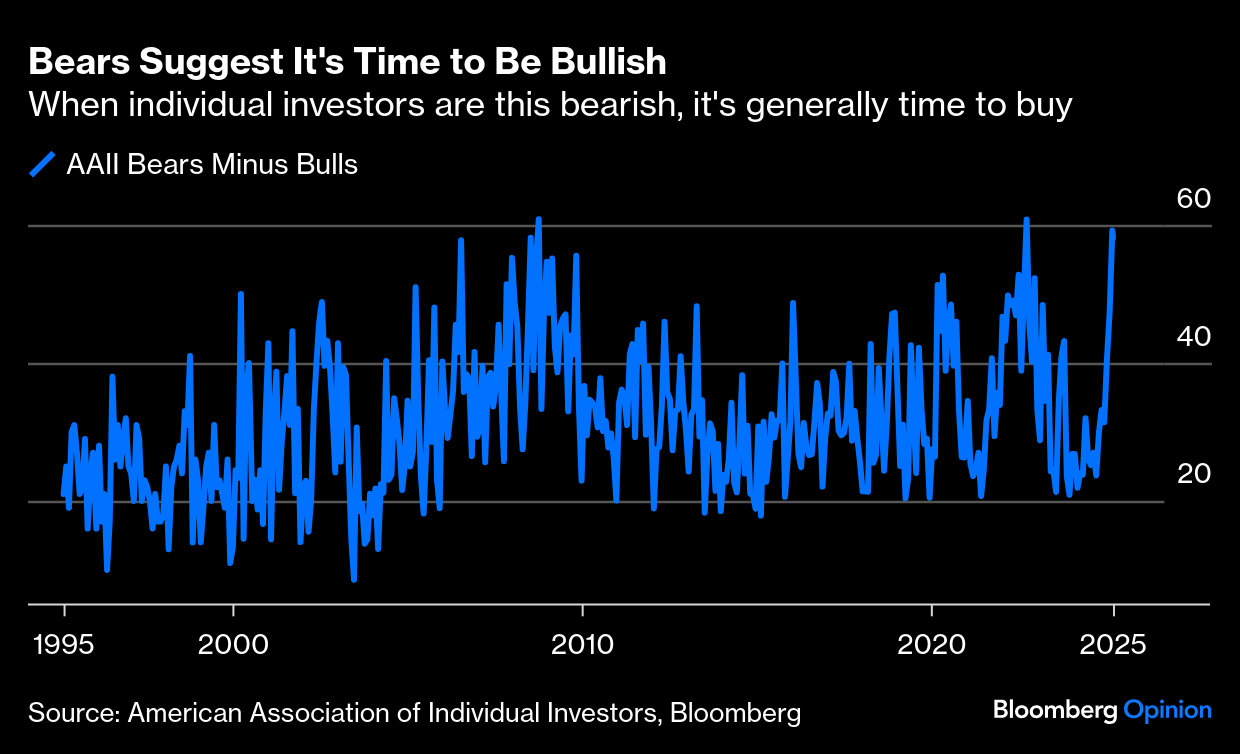

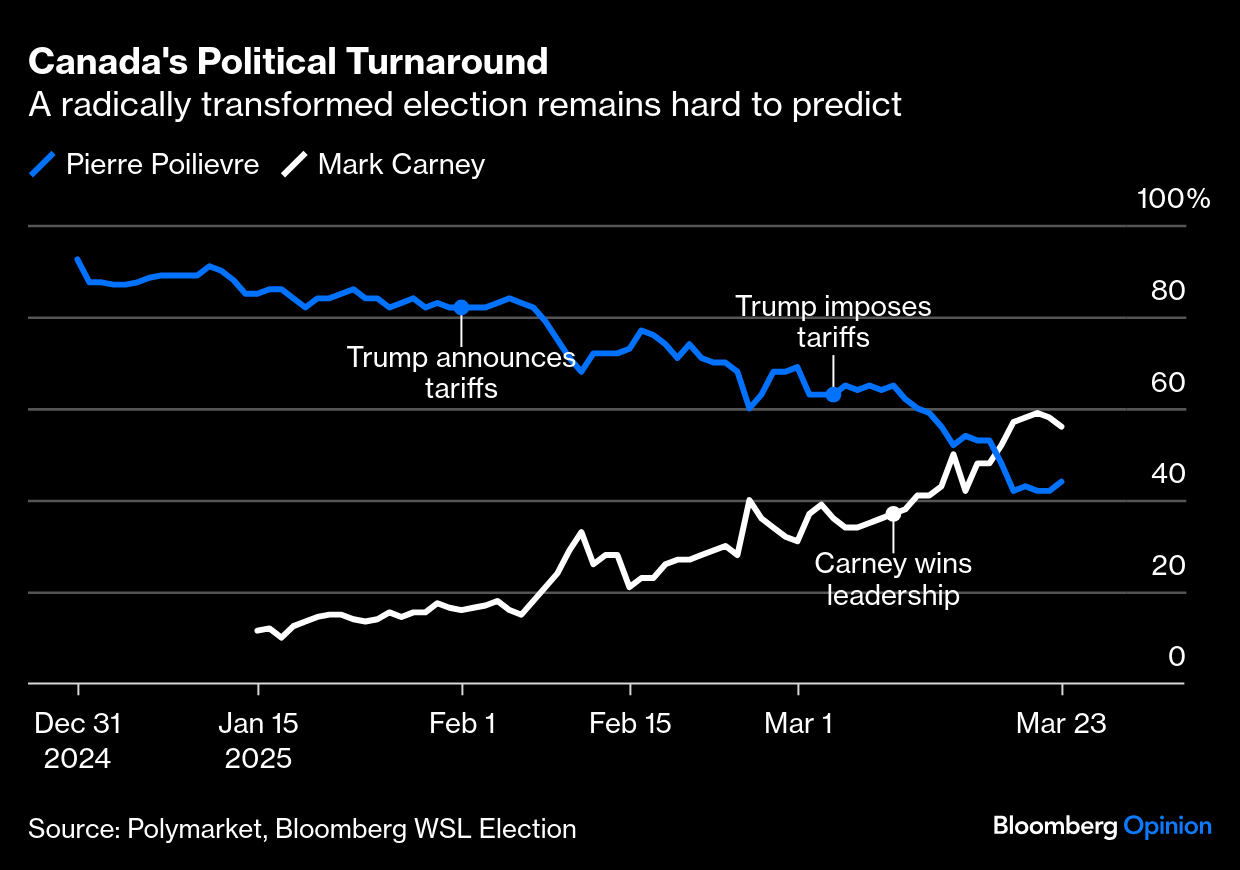

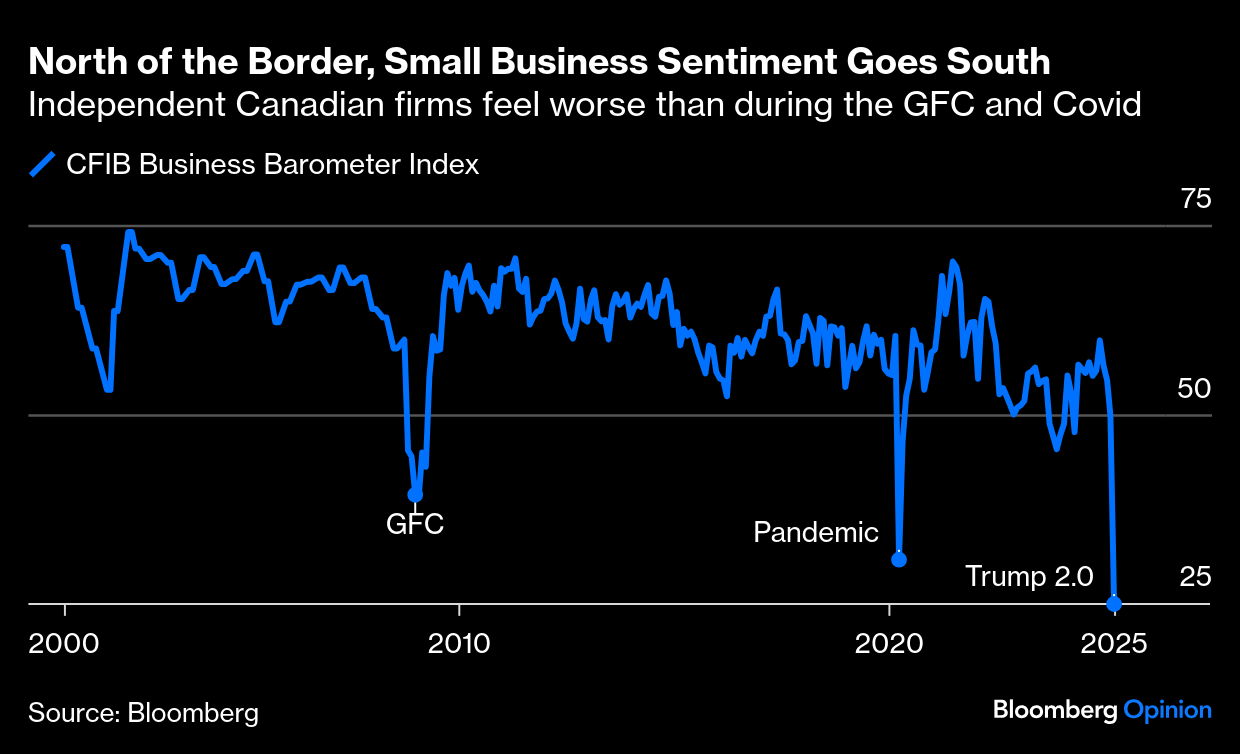

Essentially, he holds that Germany's release of the debt brake won't fuel inflation, and the ECB will likely cut twice more this year. That could snuff out optimism for the euro. And of course, Trump could impose a blanket levy on the euro zone, which would be dollar-bullish. But Germany's outsized fiscal expansion might allow it to deal with the US approach. Deutsche Bank's global head of FX research, George Saravelos, says front-loaded fiscal policy would offset the blow from tariffs by generating a muted knock-on impact on growth. That would allow the euro to withstand the might of a resurging dollar, at least for now. But there's unlikely to be much clarity on this from Liberation Day. —Richard Abbey On the face of it, there's just been a "biblical rotation" — to borrow the phrase of MI2 Research's Julian Brigden — out of the US and into stocks everywhere else, particularly Europe. That leaves investors in no man's land, and US stocks are bouncing. How seriously should we take that bounce? There's a decent argument that this is the beginning of a return to US exceptionalism. This correction, very unusually, has played out with the VIX volatility index never exceeding 30. There's nothing disorderly or panicked going on: Credit markets — central to a more significant downtrend — are also relatively unconcerned. Bloomberg's aggregate indexes for investment-grade and high-yield bonds have seen their spreads over equivalent Treasuries rise this month, but they did so from a very low level. Even now, this is nothing like the angst of the regional banking crisis two years ago, or last summer's carry trade unwind: Sentiment indicators suggest that it's time to buy US stocks. The proportion of retail investors calling themselves bears exceeds self-described bulls to an extent that in the past always preceded a big rally. When people are this bearish, it's generally time to buy: US macro data has surprised negatively of late, while European data have come in better than expected. This is illustrated by the Citi Economic Surprise indexes and would, again, justify a one-time correction for the US indexes, but not a major sea change: And then there's the fact that the US market looked implausibly exceptional. Its outperformance, even if the Magnificent Seven tech platforms are excluded, was phenomenal. What's just happened is a big correction, but it hasn't clearly set up a new trend: That led Morgan Stanley's chief US equity strategist, Mike Wilson, to contend that US underperformance was "fairly benign in a longer term context," with the S&P 500's relative strength returning to the "long-term trend line that has held for the past 15 years." Wilson added that US earnings have been revised downward over the last two months to a far greater extent than in Europe, in large part thanks to the strong dollar at the end of last year, which weakens US foreign profits. That's another reason for the US to bounce back, as the weakening dollar should help US earnings in this quarter. If this is a true financial regime change, it will be because the regime that governs US relations with its allies has also changed. If that happens, it's time to throw out the assumptions that undergird US exceptionalism. As I reported earlier this month, the reaction in Germany to JD Vance's speech to the Munich security conference, and the humiliation of Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in the Oval Office, was dramatic. Germans decided the US could no longer be trusted. A huge shift in fiscal and defense policy has already followed. Canadian sentiment may also be shifting profoundly. Three months ago, it seemed a virtual certainty that the Conservative Pierre Poilievre, a Trump-style populist, would be the next prime minister. After two months of Trumpian anti-Canadian invective, bettors on the Polymarket prediction market now think the new Liberal PM Mark Carney has the better chance: Beyond the polls, Canadian small businesses — generally run by people who don't aren't fans of the Liberal administration — have reached riot point. The Canadian Federation of Independent Business shows confidence at its lowest ebb in its survey's 25-year history: Relatively lenient tariffs on April 2 wouldn't alleviate such rage. If Canada tries to reorient its economy away from the US (no easy task), the effects will be lasting. To use a distinction from Financial Insyghts' Peter Atwater, the problem isn't so much uncertainty as vulnerability: Do investors feel confident they will be beneficiaries of President Trump or do they feel vulnerable and believe they will be victims? Whether President Trump and his team realize it, they are pushing investors to a point where they will need to decide should I stay or should I go?

If the violent switch out of US stocks was primarily a correction to an overblown trade, it's over for now. If Trump's opening verbal volleys have changed the world as much as many US allies think, there is much further to go, even after Liberation Day. A video recommendation. Ludwig, starring David Mitchell (Shakespeare in Upstart Crow), is now streaming on BritBox. He's a shy puzzle-setter who never leaves the house, and gets parachuted into a job as a murder detective. It's delightful, funny, and brilliant; just what you need at times like this.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment