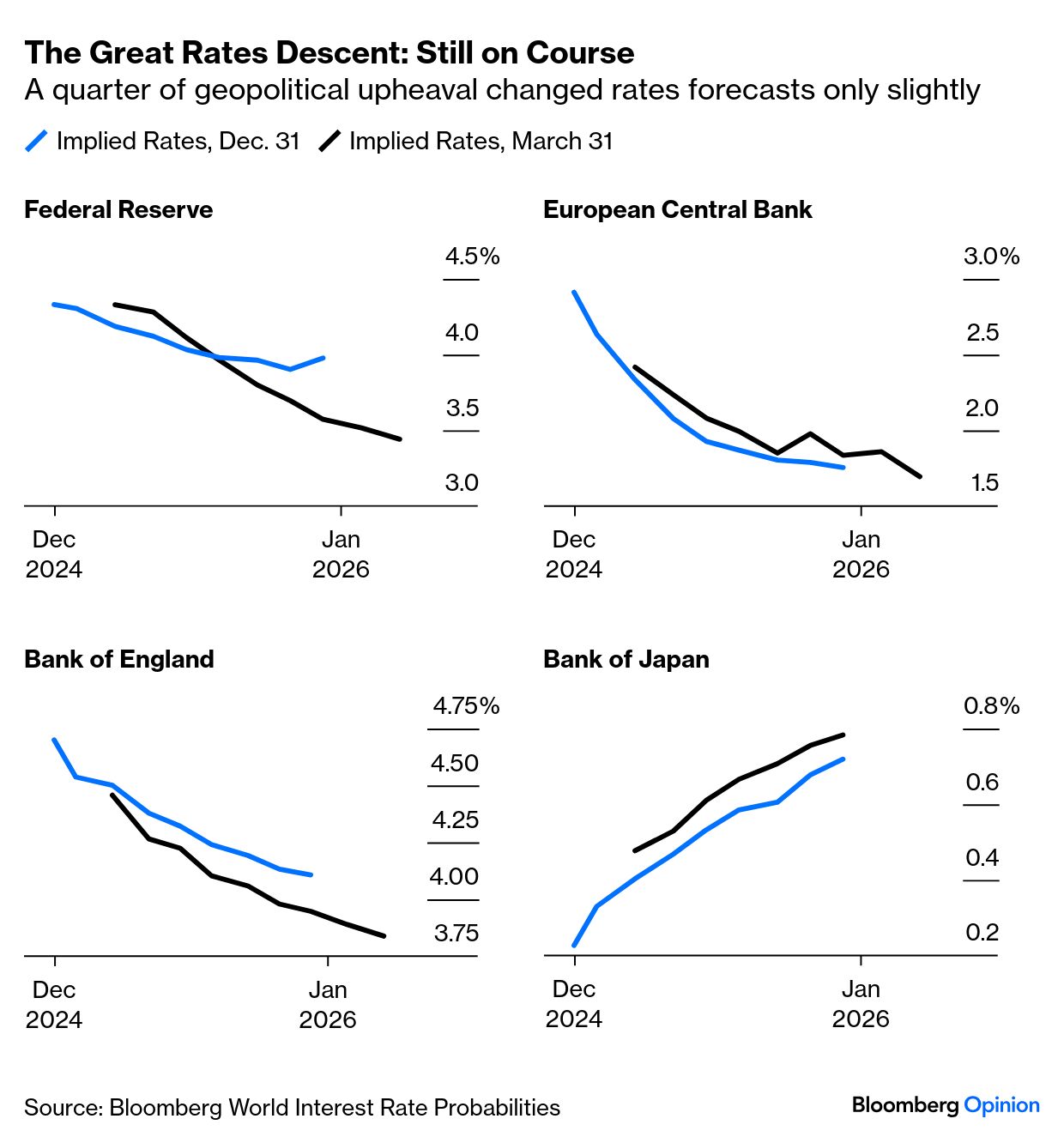

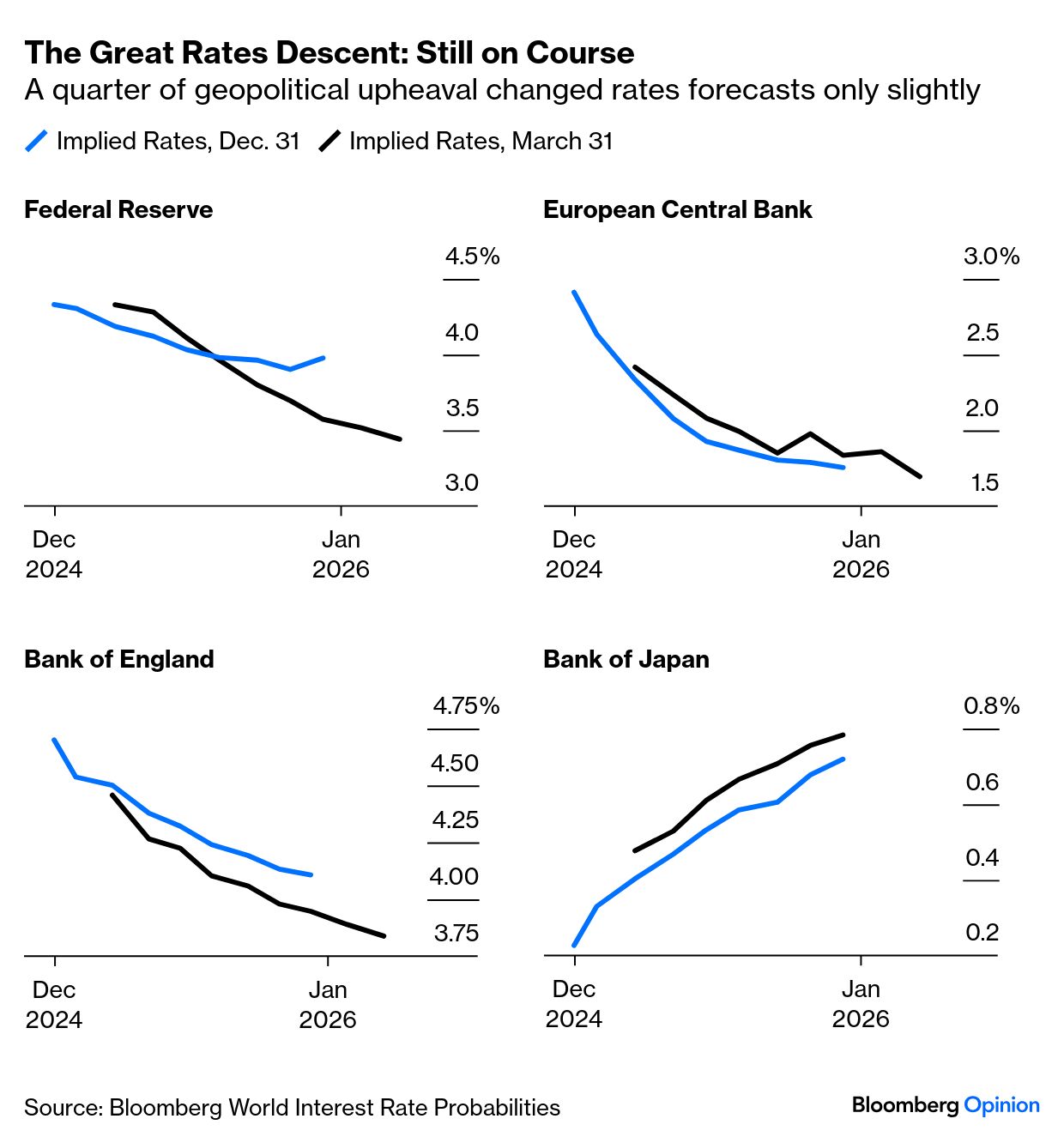

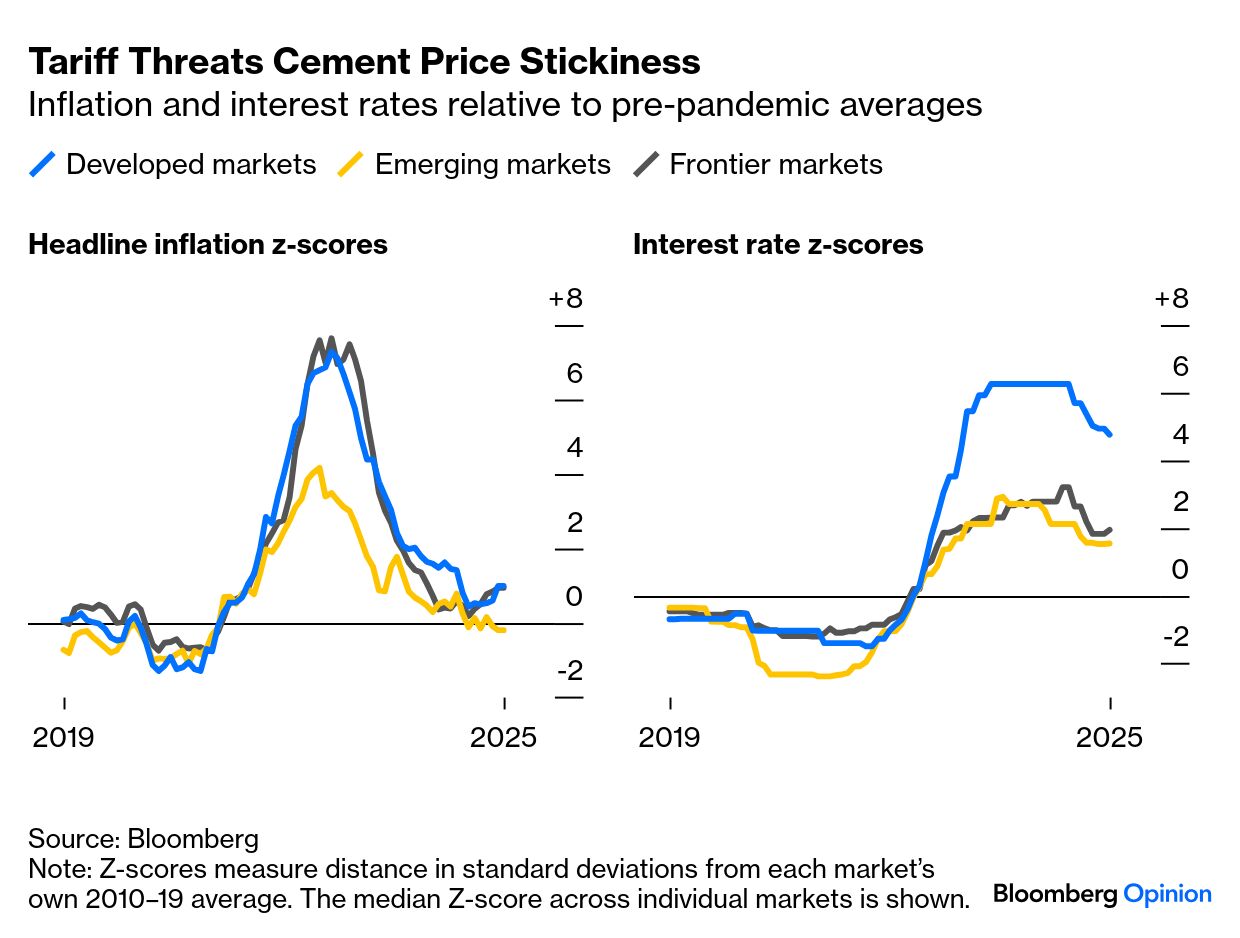

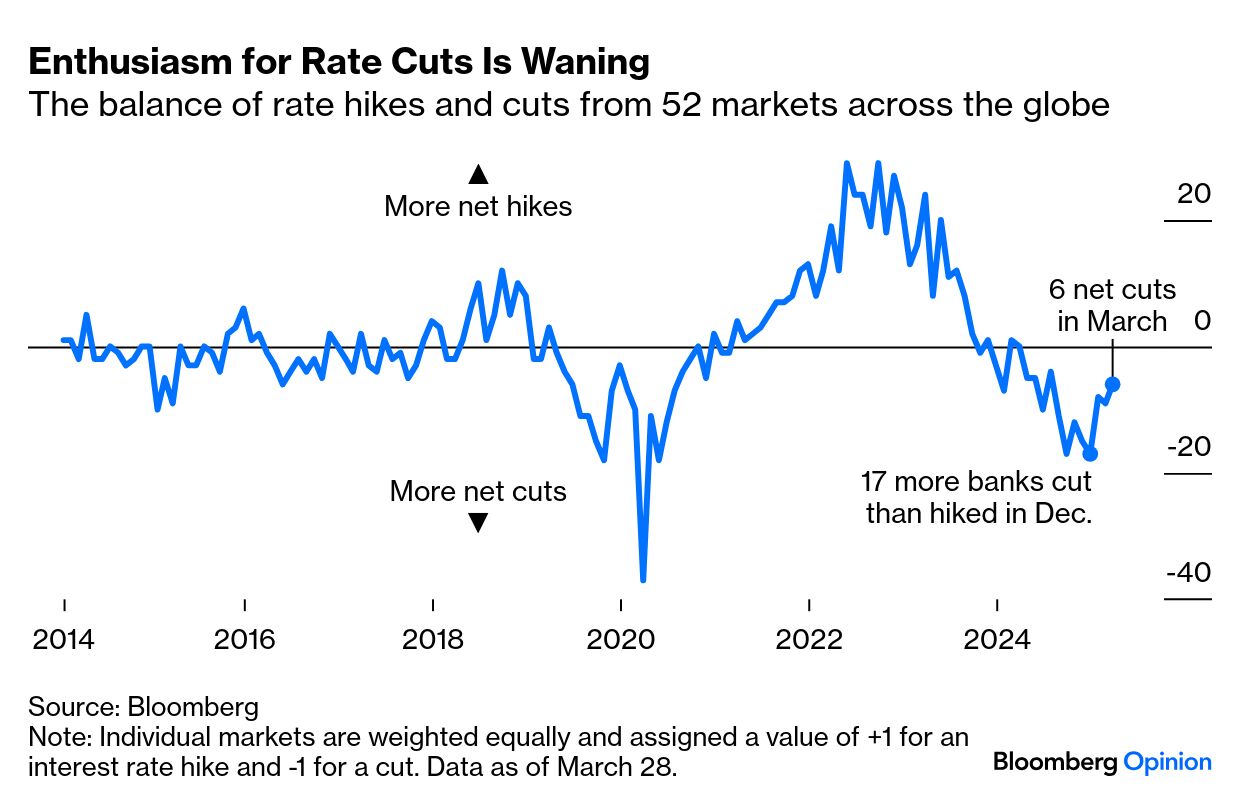

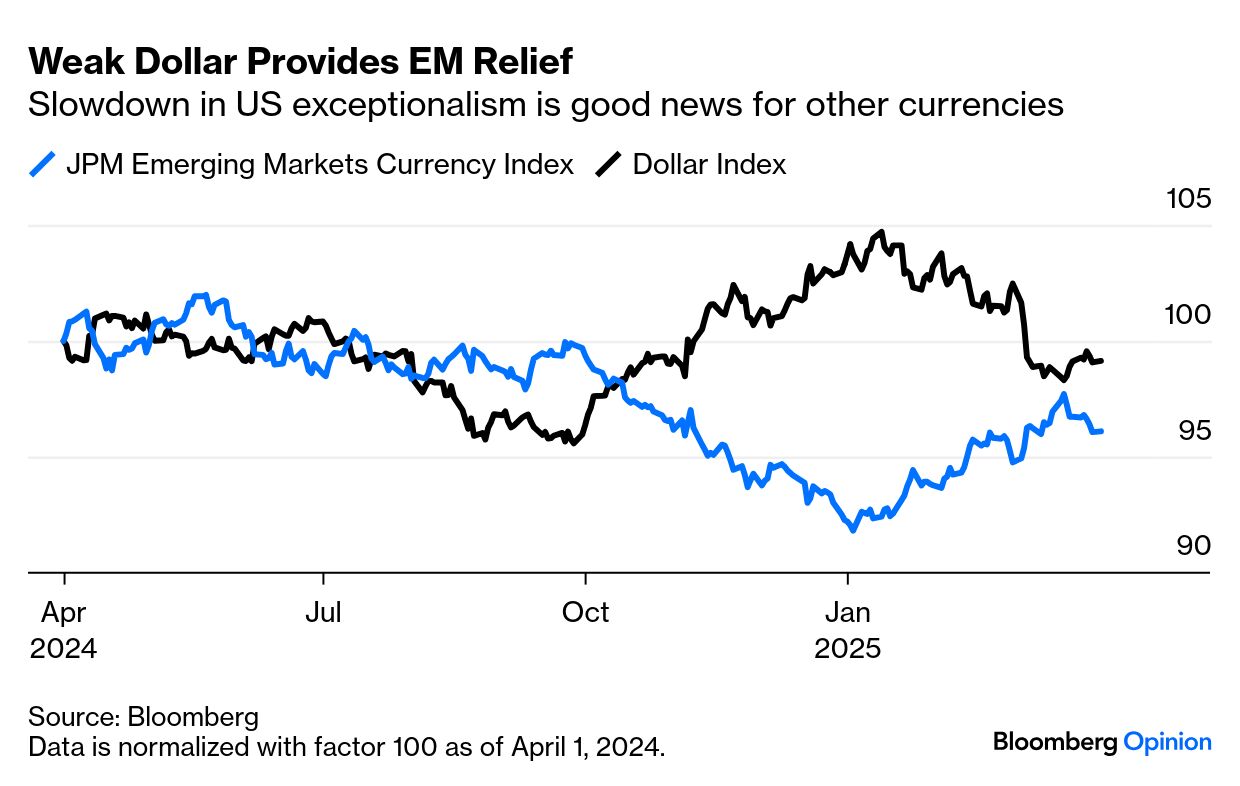

| This newsletter has been comparing the descent from high interest rates to mountaineering for more than a year. The analogy continues to work, but now needs a seismological addition. The descent is more perilous than the climb. Coordination is vital, with tired climbers roping together for safety. Throughout last year, the story was of a halting and slow descent, with central banks steadily taking the risk of letting rates reduce. Now, with the descent well advanced but still incomplete, they must contend with the tariff earthquake triggered by President Donald Trump. In mountainous terrain, this could trigger landslides and avalanches. Inflation never reached the heights of the 1970s that ignited Paul Volcker's infamous monetary policy tightening, which eventually turned out to be a masterstroke. By the turn of this year, post-pandemic inflation had been reduced to embers. While the disinflation process was frustratingly slow, and remained stubbornly above official targets, its direction of travel was not in doubt. The geopolitical excitement of the last three months had surprisingly little effect. That's because tariff policy has remained unclear, and because the risks of both slower growth (which would require lower rates) and higher inflation (which would push for raising them) appear to have risen. With possible effects canceling out, it's not so surprising that expectations for central banks barely moved. The following chart shows the implicit policy rates discounted on the overnight index swaps market as of Dec. 31 and again on March 31, as calculated by Bloomberg's World Interest Rate Probabilities service:  To some extent, the central bankers can't be expected to adjust their outlook to the new protectionist reality, as there's still no clarity on the magnitude and scope of tariffs. After Trump's promised "Liberation Day," Jerome Powell and his Federal Reserve colleagues could have to pivot swiftly. So far, though, it's noticeable that for all the sharp rises in consumer- and market-based inflation forecasts, US rates markets appear more worried about a slowdown than inflation; projected rates have fallen far more for the Fed than for other central banks. That recession risk doesn't yet show up in employment data. Despite DOGE's decimation of the federal workforce under Elon Musk, jobs numbers have held up, but the ramifications of the restructuring could well be felt down the road. Further, consumer opinion surveys by the University of Michigan and the Conference Board are increasingly gloomy. This is dangerous. Oxford Economics' Bob Schwartz points out that disappointment is sending confidence to recession levels amid growing fears of higher inflation and deteriorating economic prospects. Powell's description of the potential passthrough effect of tariffs on prices as "transitory" doesn't help, as it contributes to worries that the Fed could let inflation get out of control again. It's also clear that in most cases, the pace of price rises remains outside central bankers' comfort zone. This is most true in the developed world. Although inflation in emerging markets has stalled, they're in a better place relative to developed markets, which, incidentally, were late out of the blocks in dealing with the post-pandemic surge. The following chart employs the methodology this series has used in the past to show the impact in terms of standard deviations from the pre-pandemic norm, rather than in absolute terms. This shows an epic shock from inflation, and then a rate shock that felt far worse in developed markets. While inflation is approaching norms, rates are still very high by the standards of the the decade before Covid: Despite this, progress on inflation hasn't turned into steadily lower rates. As this diffusion index shows, there have been more cuts than hikes in each month this year. But in March, there were only a net six cuts across the world, the fewest since last summer. The great descent from high rates hasn't halted or reversed, but it has slowed down sharply. And policy tightening is no longer regarded as an abnormality: Emerging markets central banks had a proactive response to post-pandemic inflation, raising rates long before their developed counterparts. This might make them useful as harbingers of another turn upward — and so far, only Brazil and Turkey have hiked lending rates. They did so under idiosyncratic circumstances with only a loose connection to the uncertainty around potential tariffs. Plunges in their currencies forced them to act, rather than rising prices. For the broader emerging markets, however, a weaker US dollar caused by the retreat from the US exceptionalism trade has had the happy side effect of propping up their currencies. That frees central banks from dilemmas over whether to intervene. This is how the JP Morgan Emerging Market Currency Index has fared since last year: What is driving this? Gabriel Sterne, head of global strategy and EM research at Oxford Economics, argues that uncertainty over the US hasn't yet hit growth forecasts for emerging markets. American interests are affected by each policy flip-flop, while people in other countries, particularly those with few US trading ties, feel them only sporadically. It's possible there are risks lying in plain sight: While it's indeed impressive how EM business and consumer confidence has held up, we think residents are ignoring some big risks. Most of these are to the downside, including further tariff announcements that may rock EM sentiment. It remains a good time to be defensive. Trump's policy noise may be so great that markets and survey respondents have adopted an over-zealous filter.

Liberation Day could be the moment when emerging countries are forced to confront the new protectionism. It will also be an acute challenge for the Fed. Bill Dudley, former New York Fed president, describes as complacent markets' expectations that the Fed would intervene to stop "damage" wrought by the president. Bloomberg Opinion agrees that the Fed is not equipped to handle stagflation. For now, the cautious descent continues without serious mishap. We need to find out the magnitude of the tariff earthquake, and scan the slopes for avalanches. — Richard Abbey and Carolyn Silverman |

No comments:

Post a Comment