| I'm Augusta Saraiva, a reporter in New York. Today we're looking at opposition to badging in among American workers. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. - President Donald Trump is invoking emergency powers to boost the ability of the US to produce critical minerals.

- Monetary policymakers are being knocked off course by the twists of White House policy, with markets paring back interest-rate cut expectations across the globe.

- Turkey's central bank raised one of its key rates in a surprise meeting, the latest move by authorities to reverse a decline in the lira.

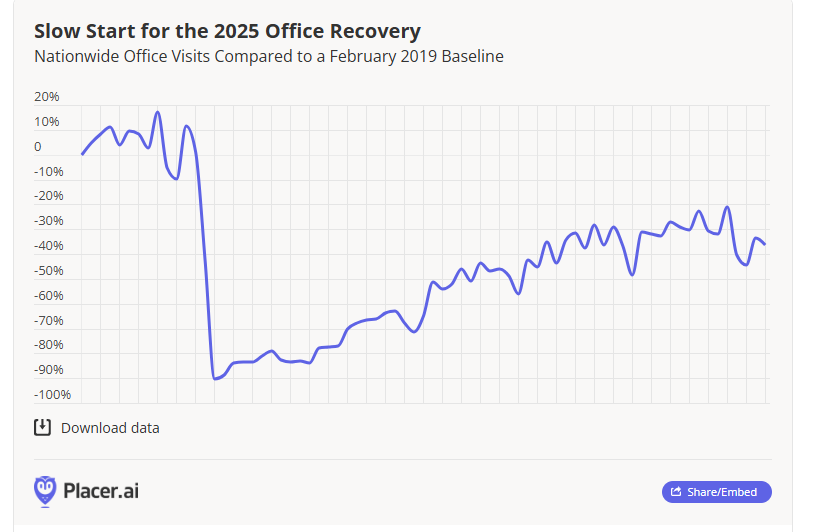

Despite efforts by corporations and the government to get US employees to badge in five days a week, office attendance was still down by more than a third in February from its pre-pandemic levels. The rising opposition to remote work by employers is hardly a US phenomenon, but it took a new level when Elon Musk, with Trump's blessing, threatened to suspend federal workers who didn't comply. Still, progress to get people fully back to work in person has mostly flatlined in the country.  Source: Placer.ai Many workers have pushed back against in-office mandates, in part because they got used to the years of flexibility. Another factor at play is the lengthier commutes. A recent National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that US employees lived about 11 miles (17.7 kilometers) farther from their workplace in 2023 compared to pre-pandemic, and one in ten people hired after March 2020 lived at least 50 miles from their office — three times the 2019 share. Highly paid employees in their 30s and 40s and in sectors like finance and professional services were more likely to live even farther from the office. The pandemic has reshaped the geography of US labor markets, the authors argued. Apart from a few cities like New York, where the majority of workers are back in the office, remote and hybrid work appears to be entrenched. Take San Francisco, for example. Five years after the start of the pandemic, the city continues to struggle with record office-vacancy rates. That's part of the reason why OpenAI's Sam Altman and Salesforce's Parker Harris are among the ultra-rich behind a new partnership aimed at bolstering the city's economic fortunes and tackling crime. The Best of Bloomberg Economics | - Two months into Trump's term, administration officials are rejecting the notion Trump has already taken ownership of an economy on which he vowed to work a "miracle."

- Japan's households reduced their collective stash of cash at the fastest pace on record last quarter as they sought to cope with rising costs of living.

- Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney is set to call a national election within days, seeking his own mandate from voters at a time when the country's businesses have been shaken by a trade war with the US.

- Germany's landmark spending bill passed its final hurdle. That largess is pulling up borrowing costs across Europe, reigniting jitters around fiscal stability on the continent's periphery.

- Chancellor Rachel Reeves is set to overshoot her borrowing forecasts significantly for the current fiscal year.

- Trump is upending international markets with his aggressive and unpredictable escalation of tariffs on allies and enemies alike. Here's a compilation of all the measures imposed, threatened, or suspended for now.

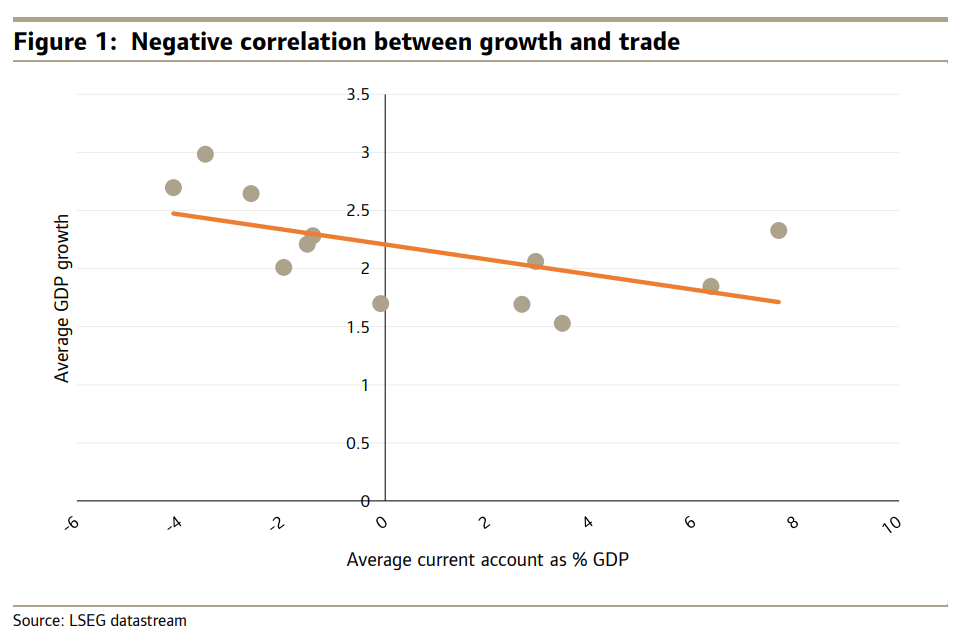

What's in an economic indicator? Trump portrays the US trade deficit as an illustration of how other countries are "ripping us off." But Steve Barrow, a longtime analyst of macro trends, points out that deficits tend to be correlated with better economic performance. At least, that's true for developed nations, Standard Bank's G10 strategy head says. (Poorer ones risk bond and currency-market runs if they sustain large deficits, but rich ones generally don't face that constraint.) As the chart below illustrates for a dozen developed nations, "stronger growth and weaker current account balances tend to go hand in hand," Barrow says. "The average German current account balance since 1980 has been in surplus to the tune of 3.5% of GDP. In contrast, the US has run with an average deficit of 2.6% of GDP over the same period," Barrow wrote in a note Wednesday. "But in spite of the US's weak trade position, average GDP growth has been just over 2.5% through the period; a full percentage point above Germany's." |

No comments:

Post a Comment