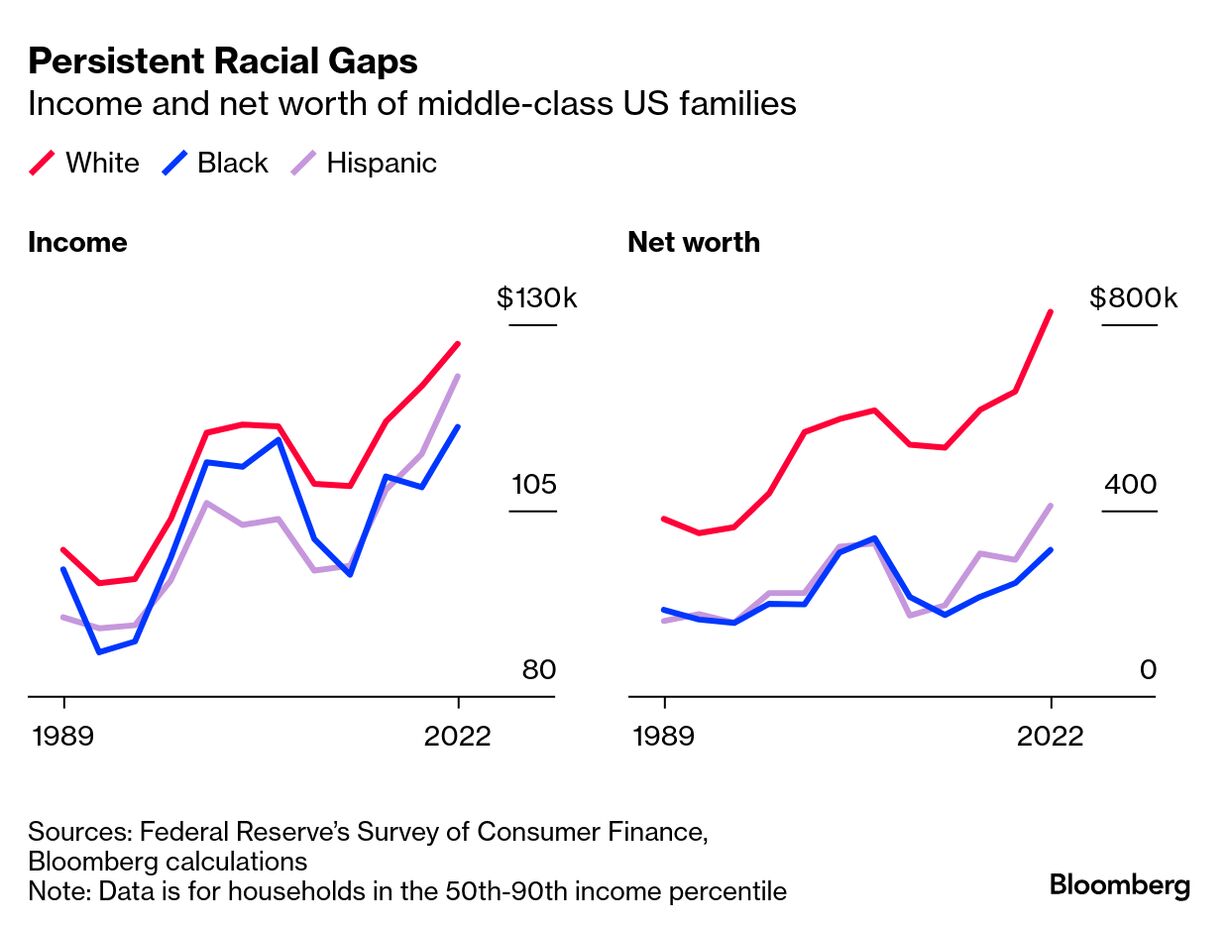

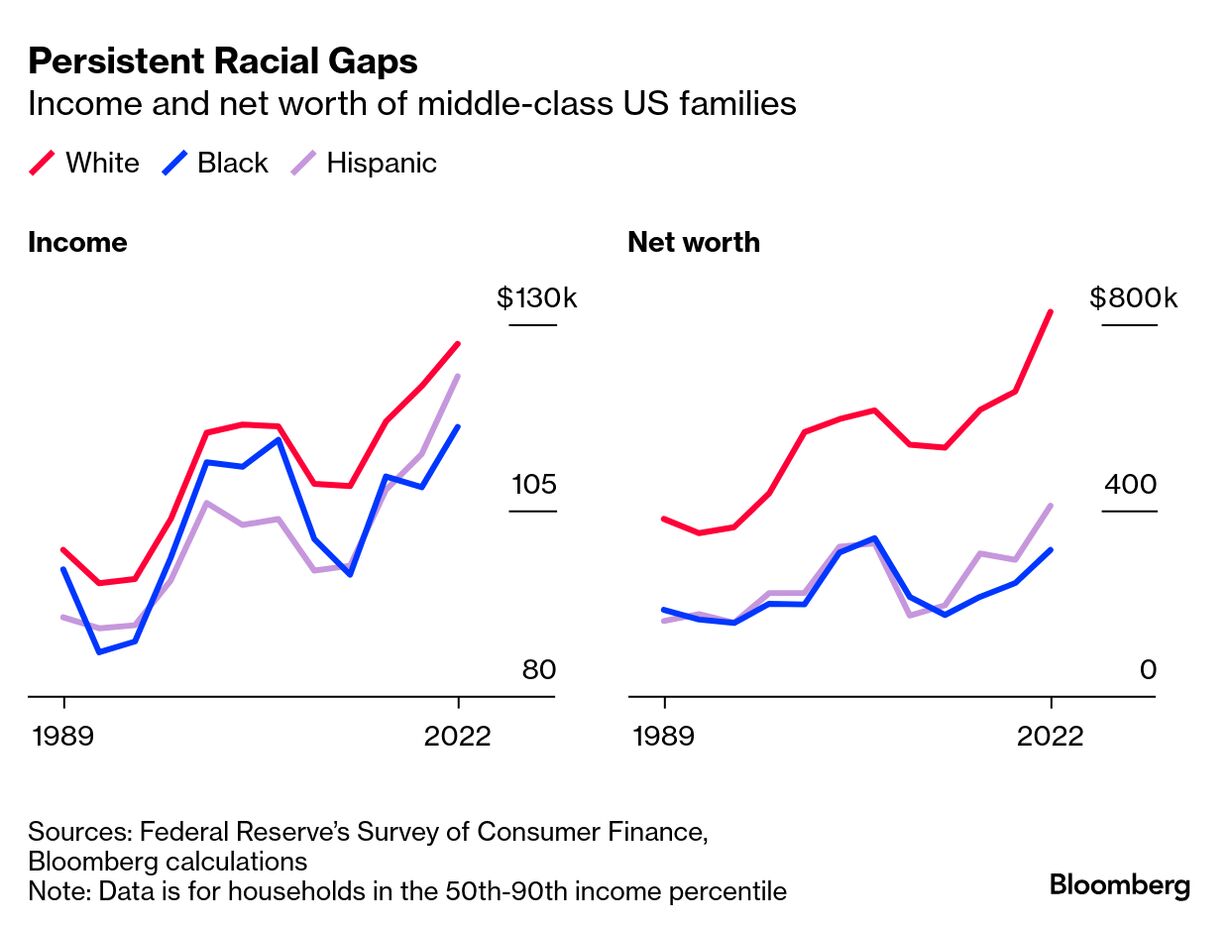

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today, Shawn Donnan writes about how a Harvard study spurred Charlotte, North Carolina, to give more support to first-time homebuyers as a way to drive social mobility. The city is also adding to its housing stock. You can find the whole story online here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. President Donald Trump's attacks on diversity programs may have changed the tenor of the conversation on inequality, but in the great heap of America's intractable problems, the economic gap between its Black and White citizens still sits near the top. Studies and government reports—diagnosing the symptoms, describing the deep roots in history from slavery to redlining and laying out the consequences—have been piling up for decades. Black Americans today earn two-thirds of what White Americans do. They are less likely to own their home. And they tend to die younger. The list is so long and familiar that the solutions researchers discuss can seem either hopelessly grand or merely incremental. And then you meet someone like Zayn Bey. At 30, Bey is the mother of two boys. She drives an Amazon truck—not the kind that delivers packages to your door but a big rig that shuttles among the company's warehouses in the area. She also has a side hustle selling beauty products and speaks confidently of a bigger future for her and her sons. "Middle class? I'm striving for a little bit higher," Bey says. "But we're going to start there." What really sets her apart, though, is that she's the beneficiary of a city's own reckoning with its economic failures. And that the reckoning has led to a new approach offering a model for other US cities. Because in the realm of solutions to America's racial wealth gap, it's one that looks neither hopelessly grand nor merely incremental. Bey last year got the keys to a newly built $265,000 three-bedroom town house in Charlotte, North Carolina. After years of being outbid by cash-wielding buyers, she finally succeeded thanks to more than $100,000 in grants and no-interest loans that allowed her to make a down payment. This meant she immediately had significant equity—wealth she didn't have before. That there even was a town house she could afford was thanks to the work of a nonprofit developer that receives funding from the city, as well as philanthropies and banks. "This is not my forever home," Bey says. "This is definitely a startup for me and my family." Which is exactly the point of the program. The push by Trump and other Republicans to not just curtail but erase the diversity, equity and inclusion policies that for decades have sought to bring some balance to America's unequal economy poses an existential threat to that goal. They argue that policies from affirmative action to home ownership programs aimed at helping Black communities get in the way of the free market and discriminate against White Americans. But for those working to narrow that stubborn racial economic gap, the combination of generous down payment assistance and a home built specifically for the recipients of that help is an example of the sort of radical rethink needed to close a chasm the data shows is growing.  Charlotte, a city of more than 900,000 people that hosts the corporate headquarters of Honeywell International Inc. and Bank of America Corp., has been a model for the economically and culturally vibrant New South for decades, and it ranks as one of the fastest-growing cities in the US. Charlotte's sales pitch has been built around good jobs and a rich quality of life at an affordable price. It offers everything from arty warehouse districts, where the rent on a one-bedroom apartment in a new development is around $1,500, to suburban gated communities with golf courses, where a little under $2 million will buy you a five-bedroom, seven-bath, 7,100-square-foot faux château. But in 2014, Charlotte's image was tarnished when a landmark study by Harvard University economist Raj Chetty ranked the city dead last for economic mobility among the top 50 metro areas in the US. The version of the American dream that Charlotte was peddling wasn't accessible to the Black residents who grew up in the city's poorest neighborhoods. It was, the glossy Charlotte Magazine declared, "our lowest low." "A lot of folks, especially those who had been here for a while, were shocked and embarrassed. It was like, 'Oh, my God, my slip is showing,'" says Victoria Watlington, a city council member. The council convened a special task force to look into the causes of Charlotte's dismal ranking. One thing it uncovered is that local development officials thought their core mission was to create white-collar jobs—and import workers to fill them. Developing local talent, particularly from the city's downtrodden Black neighborhoods, was not designated as a priority.  Watlington at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Government Center. Photographer: Rose Wind Jerome for Bloomberg Businessweek "They were being measured on how many high-paying jobs are moving to Charlotte, not how many people are moving upward, or how many people who are homegrown are getting these jobs," says Brian Collier, who led the writing of the 2017 task force report and now serves as president of the Gambrell Foundation, a local philanthropy. Local leaders quickly realized that homeownership needed to be a focus, particularly in a place like Charlotte, where the supply of affordable homes is under constant stress from the growing population. The city in 2022 successfully got voters to back a $50 million bond to pay for the construction of affordable homes and down payment assistance for two years. In November 2024, the city went even further, with voters overwhelmingly endorsing a $100 million bond to fund affordable housing projects. At the heart of that strategy are groups like DreamKey Partners Inc., the local nonprofit developer that built Bey's new home. In 2023, DreamKey began working with the city on a pilot project that helps prospective buyers pull together money from the city's down payment assistance program and similar programs run by the state and private-sector lenders. The goal is not just to help buyers rise above the 20% equity threshold, below which they have to purchase mortgage insurance, but also to give them additional equity—and wealth. "We said, OK, we've got to be much more aggressive when it comes to homeownership if what we're really trying to do is change outcomes," Watlington says. Keep reading: How Public Shaming Helped Create a Promising US Housing Program |

No comments:

Post a Comment