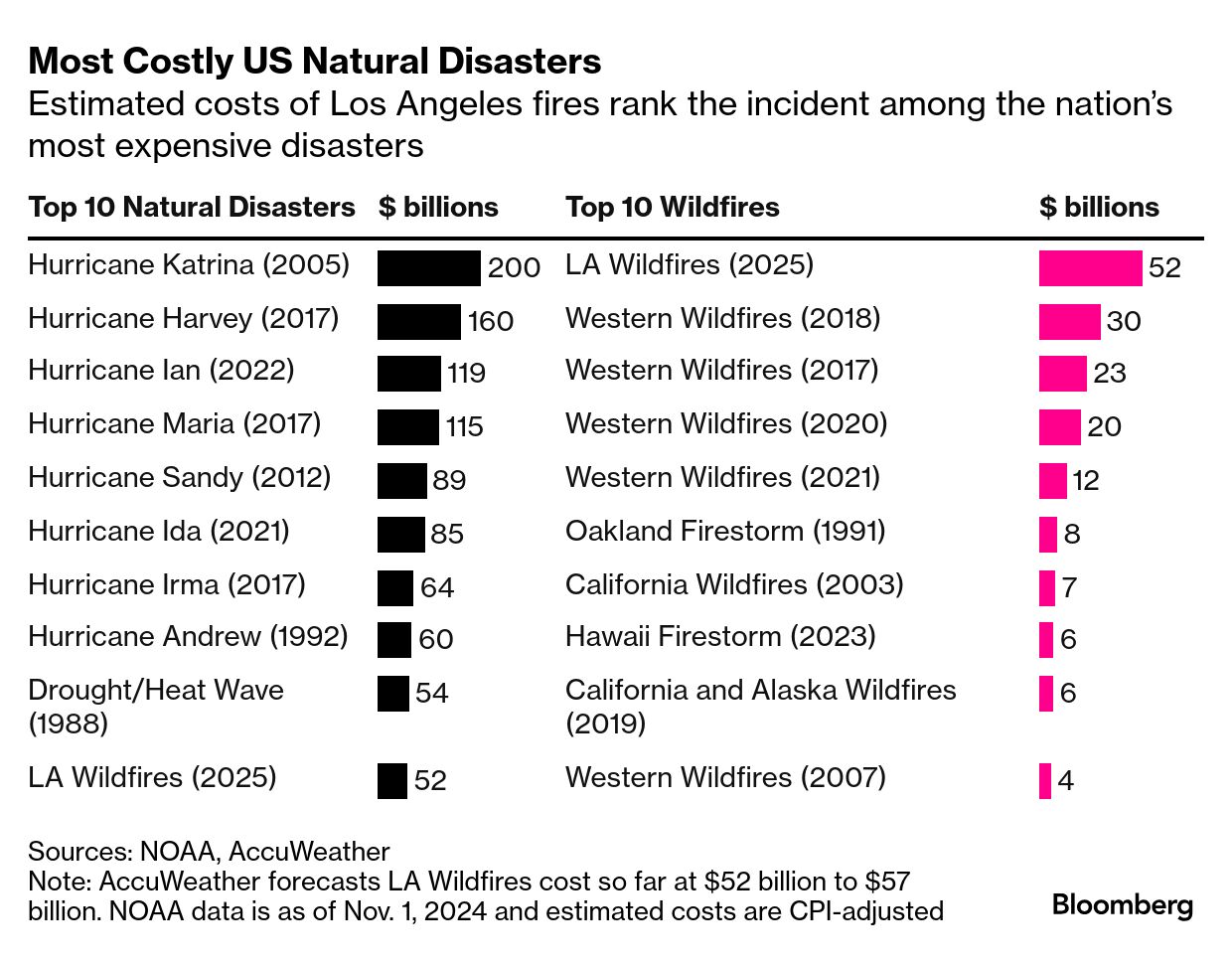

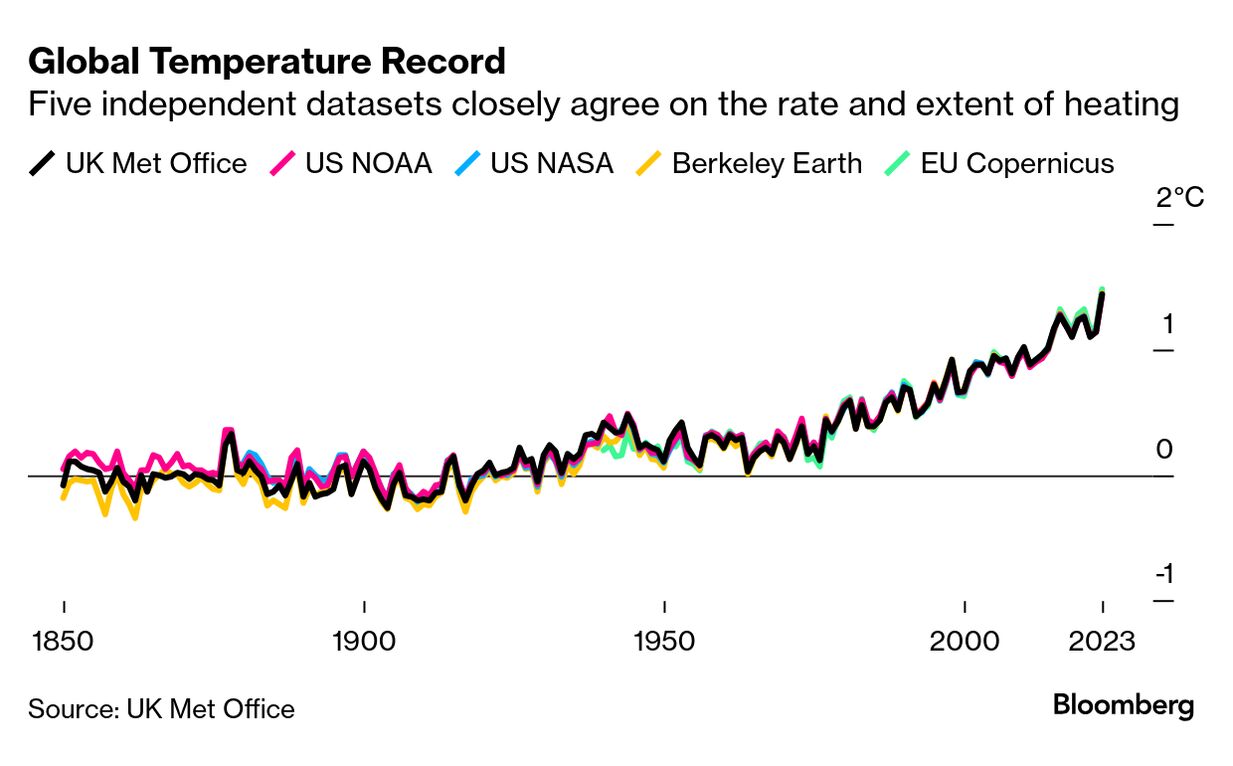

The debate over private firefighters for the rich | By Todd Woody and Maxwell Adler As his Los Angeles neighborhood burned on Tuesday, resident Keith Wasserman posted a plea on X: "Does anyone have access to private firefighters to protect our home in Pacific Palisades? Need to act fast here. All neighbors houses burning. Will pay any amount." Wasserman, cofounder of real estate investment firm Gelt Venture Partners, sparked outrage online, renewing debate about the role of private fire-fighting services as increasingly fast-moving, climate-driven wildfires overwhelm governments' ability to respond. Wasserman's X account has since been deleted and he didn't respond to a request for comment. Private firefighters were being deployed in Los Angeles as several wildfires continued to burn out of control on Wednesday, incinerating more nearly 30,000 acres, forcing tens of thousands of people to evacuate and destroying more than 1,000 structures. But the role of private firefighters and their effectiveness in an era of catastrophic conflagrations isn't clear cut.  Houses burn during the Palisades Fire in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood. Photographer: Kyle Grillot/Bloomberg The hurricane-force winds that drove the extreme speed of the Palisades fire and forced residents to flee for their lives would have left little time for private fire-fighting teams to respond, according to Don Holter, an owner of Mt. Adams Wildfire, a Northern California fire-fighting service. "With those kind of winds, the fire is coming straight at you and there's nothing you can do to stop it." Holter said. Private fire-fighting services for hire have drawn criticism in recent years. When Kim Kardashian and Kanye West credited private firefighters with saving their $60 million Los Angeles mansion from a 2018 wildfire, the move was seen as a sign of widening inequality, with the rich paying to protect their property with everyone else left to sift through the ashes. Covered 6, a Los Angeles-area security firm, is assisting cities with evacuations and fire suppression, according to company founder Chris Dunn. "There is no replacing, or circumventing, or subverting public safety," said Dunn. "There's only augmentation and support." Read the full story on Bloomberg.com. What role is global warming playing in the fires? A stubborn high-pressure ridge has blocked moisture from reaching Southern California for months, creating a virtual force field that has led to dry conditions. Researchers say prolonged fall and winter dry spells are likely linked to warming oceans, which can cause the jet stream — the band of fast-moving winds that control weather across North America — to wander off its usual track. That leaves high-pressure ridges stuck in place. It's another example of how a warming world wreaks havoc with weather. Why is wind creating a problem for containing the blazes? Earlier this week, firefighting aircraft were grounded due to intense winds, hampering efforts to combat the wildfires. Powerful Santa Ana winds have also been fueling dangerous fire behavior in the Los Angeles area and were the main culprit behind the spread of the Malibu fires in December. Read more about the Santa Ana winds here. What's the next step in the firefight? Officials are under immense strain to contain the fires, which have scorched some 27,000 acres, upending life in America's second-largest city. On Thursday US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said the Pentagon is ready to provide aircraft to help extinguish the flames from the sky. "Many US military installations in the area have personnel and equipment that can also be surged to fight this awful blaze," he said. For weather insights sent straight to your inbox, subscribe to the Weather Watch newsletter. Climate change is speeding up | By Eric Roston Scientists sounded the alarm long before last year ended that 2024 would become the hottest year on record and almost certainly the first to surpass the 1.5C limit to global warming, set out as a goal in the Paris Agreement. Now both of those milestones are expected to be confirmed on Thursday and Friday in official statistical releases from scientific agencies, including the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the UK Met Office. What's puzzled scientists is the clear acceleration in rising temperatures, even as the evidence of the fast-warming atmosphere became impossible to miss. The hottest day ever recorded happened on July 21, 2024 — a record that held until July 22. The planetary heatspike was made 2.5 times more likely by greenhouse gases, according to researchers. Typhoon Gaemi in Asia and Hurricanes Helene and Milton in the US, similarly juiced by climate change, killed hundreds of people and caused colossal damage. There was flooding across Africa's Sahel and in southeastern Spain; drought in southern Italy and the Amazon River basin; wildfires in central Chile; and landslides in northern India. Hottest-year status, awaiting confirmation, would put 2024 in rarefied company. The warmest year up to now, by a substantial margin? 2023. But while the heat is clear, scientists are struggling to account for the speed of this recent jump. Something's pushing up temperatures faster than expected, and the climate detectives have yet to agree on what. After months of research and debate, they have collected suspects — and already let a few go — in what's become the greatest climate mystery in 15 years. "The science tells us that we should expect surprises like this," said Sofia Menemenlis, a Ph.D. candidate in atmospheric and oceanic sciences at Princeton University. "This is not something that should be completely unexpected in the future, knowing what we know about global warming." Read the full story on Bloomberg.com Last year's catastrophes were the costliest since 2017. At $140 billion, insured losses from natural disasters globally were more than double the 30-year average of roughly $60 billion, according to industry data compiled by Munich Re and published in a report. Fires aren't the only natural disaster to worry about. Flooding poses the greatest threat to supply chains this year, as warm ocean temperatures fuel more frequent and disruptive storms, including powerful hurricanes, according to a report from Everstream Analytics. Is there any good news? US greenhouse gas emissions and economic activity typically grow in tandem. But there are indications that the two are beginning to diverge, in an optimistic sign for the climate. In December, Europe's Copernicus weather service announced that it was "virtually certain" that 2024 would be the hottest year ever. What's more, the global average temperature last year appears to have surpassed 1.5C for the first time, blowing past a threshold that's taken on enormous significance in the fight against climate change. Does that mean governments, corporations, and activists recalibrate their climate goals? Akshat Rathi speaks with reporters Eric Roston and Zahra Hirji about what this new reality means. Listen now, and subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or YouTube to get new episodes of Zero every Thursday.  Carbon offsets — a controversial tool companies use to try and make up for emissions — could be worth as much as $1 trillion by 2050, according to Bloomberg NEF. But this lucrative sector has problems. Already plagued by dubious claims known as greenwashing, it faces new challenges like those at Indonesia's Rimba Raya, one of the largest carbon offset projects in the world. Watch the latest video from Bloomberg Originals on the fight for a share of this $1 trillion market in Borneo's jungle. |

No comments:

Post a Comment