| I'm Chris Anstey, an economics editor in Boston. Today we're looking at possible implications of a surprise personnel announcement at the Federal Reserve. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. Less than two months ago, Michael Barr, the Federal Reserve's vice chair for financial supervision, declared at a congressional hearing that he intended to keep serving as the Fed's top banking cop until his term was up in July 2026. On Monday, he declared that he'll instead be bowing out of that job next month, if not sooner. The background: Barr pursued a financial-regulation agenda very much at odds with the hands-off approach favored by President-elect Donald Trump and fellow Republicans. Chair Jerome Powell in November had declared that the law doesn't permit the president to remove Fed board members from positions of responsibility. Nevertheless, Barr in a statement Monday indicated concern about his role becoming a "distraction." He told Bloomberg News "the practicalities" of staying on and facing potential litigation became clear to him over the holidays.  Michael Barr, vice chair for supervision at the US Federal Reserve Photographer: Allison Robbert/Bloomberg In a possible riposte to any criticism that Barr was compromising Fed independence, though, Barr decided to retain his Fed board membership, which is set to run until 2032. And because the banking cop must be a member of the board, that leaves no opening for Trump to name someone new. Which sets the stage for early potential conflict between the incoming president and the Fed. An easy solution for Trump would be to tap Governor Michelle Bowman, whom he nominated for the board in 2018, for the supervision role. But Trump isn't known for favoring easy solutions. And Barr's plans would still leave him sitting on the board whenever his successor takes up the job, scrutinizing and casting votes on what's bound to be a far laxer set of financial proposals. "Staying as governor in ways that constrain Trump could spark tension after a period of détente that has been welcomed by markets," Krishna Guha and Marco Casiraghi at Evercore ISI wrote in a note Monday. That détente had stemmed from Trump's indications he wouldn't attempt to oust Powell — whose term as as Fed chair runs until May 2026 — from the top job. Guha and Casiraghi didn't rule out the potential for Trump's team to effectively name a vice-chair-in-waiting, with the individual taking up the job whenever a board opening materializes. As the next one isn't scheduled to come for a year, that leaves plenty of opportunities for new twists and turns. The Best of Bloomberg Economics | - China's central bank expanded its gold reserves for a second month in December, signaling renewed appetite after temporarily pausing purchases last year.

- Germany's dream of becoming a semiconductor superpower and reestablishing Europe as a pillar of global prosperity are fading fast.

- Indonesia has joined the BRICS group of developing nations, potentially bolstering the Global South as Donald Trump's trade policies pose risks to world economy.

- US dockworkers will restart talks to avert a halt to roughly half of the country's container volumes, with shipping rates already spiking at the start of the year.

- The leaders of Malaysia and Singapore are set to formalize an agreement establishing a special economic zone linking their two nations' border region.

- UK house prices slipped back for the first time in nine months even as the property market enjoyed its best year since the pandemic, Halifax said.

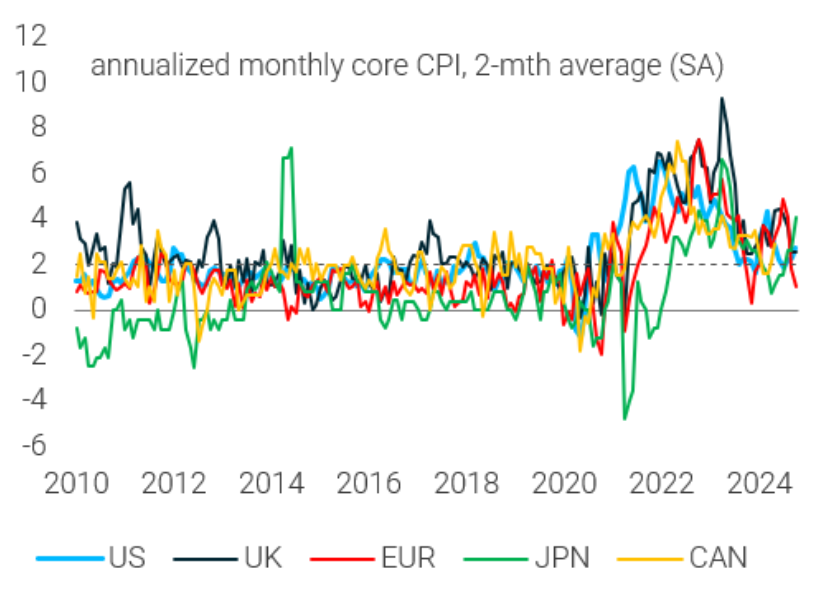

Central banks in advanced economies indicate they plan to keep lowering interest rates this year despite, in many cases, inflation not having come back down to their 2% targets — effectively revealing they're comfortable with rates nearer 3%, according to Dario Perkins at TS Lombard. Particularly with respect to core price gauges, "in most jurisdictions, it is clear that these supposedly 'underlying' rates of inflation remain closer to 3% than 2%. Central banks still haven't completed that 'last mile' of disinflation," Perkins wrote in a thread on Monday. As long as economies remain stable, and tariff hikes prove to be limited, 3% inflation actually isn't such a bad thing, he argues. "So far, this looks healthy – the deflationary bias from the 2010s is gone," he wrote. After spending around a decade at zero interest rates, "it wouldn't be a disaster if we faced the next recession – whenever that happens – with inflation above target." |

No comments:

Post a Comment