| I'm Chris Anstey, an economics editor in Boston. Today we're looking at the year ahead for emerging markets. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. - Economy in US counties that Donald Trump won points to his governing challenges.

- China's latest move to try and boost spending: subsidizing smartphone purchases.

- Joe Biden has decided to block the sale of US Steel to Japan's Nippon, ending a $14.1 billion deal that has faced months of vocal opposition and raising questions over the future of a US industrial giant.

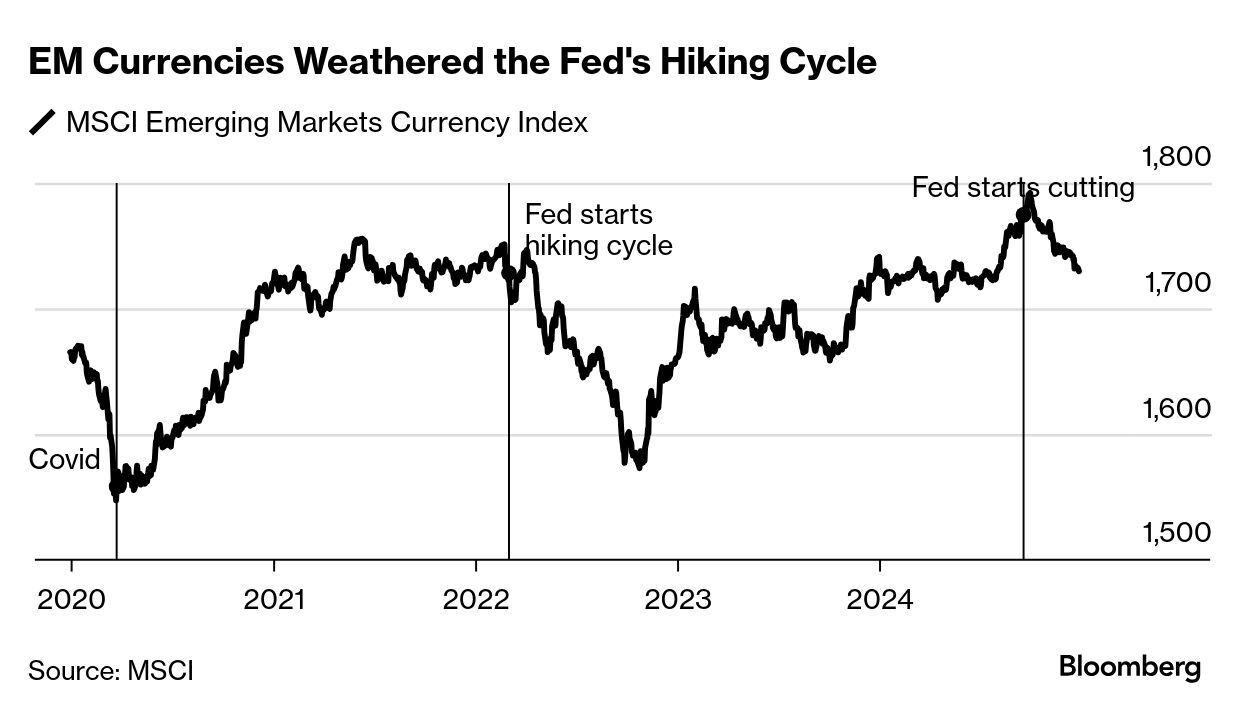

So goes one, so go them all. That used to be the general rule of thumb for developing nations. When Thailand's currency crashed in 1997, it was a matter of time before crisis enveloped nations from Russia to Brazil. Just a few years after the Asian financial crisis morphed into a global phenomenon, economic policymakers in US President George W. Bush's administration tried to encourage investors to look at each emerging market on its own merits. Just because Argentina and Turkey found themselves in trouble, that shouldn't mean everyone else got walloped. The effort found middling success. But what's clear today is that individual emerging economies to a great extent really are judged differently. Just in recent weeks, central banks in Chile and Colombia lowered interest rates while Brazil's hiked them. Indonesia has for months held off on cutting its benchmark as it sought to prop up its currency, while Southeast Asian neighbor the Philippines capped off 2024 with a third straight cut. Also curious based on previous decades' experience: emerging market currencies weathered with aplomb the Federal Reserve's most aggressive monetary tightening cycle in four decades. The MSCI Emerging Markets Currency Index dropped just 4.3% in 2022, then recouped that loss in 2023. But in 2024, as the Fed kicked off an easing cycle, the index fell. The break with past patterns reflects in part the greater sophistication — and sheer size — of many emerging economies. Indonesia and Turkey are now $1 trillion economies, and Brazil weighs in at over $2 trillion. The Philippines is eyeing entry to the $1 trillion club in 2033. That means much bigger domestic demand, and more sophisticated financial systems. It all means investors need to look at each emerging market on its own merits. The 2025 outlook from the Bloomberg Economics team, led by Tom Orlik, showcases that approach, with forecasts that vary notably based on each nation's particulars. The following are among selected projections: - India's growth is seen rebounding to 7.6% in the fiscal year through March 2026, as a recovery that started in the final months of 2024 gathers pace.

- South African growth will likely accelerate to 2% over the medium term, from sub-1% in the past decade. Positive sentiment around the business-friendly broad coalition will draw job-creating investments.

- Turkey's GDP will climb 3.1% in 2025, a far cry from average growth rates above 5% in the decade leading up to the pandemic. Rampant inflation has necessitated high rates.

- Indonesia is well positioned to ride out external headwinds, being more reliant on domestic demand and having lighter demographic headwinds than many. It's also a key supplier of metals needed in the transition from fossil fuels. GDP to rise 5.1% in 2025 after 5.0% in 2024.

- Mexico's growth will slow to 1% from 1.3% in 2024, with the main drag coming from lower investment due to uncertainty about the future of bilateral relations with the US.

- Brazil's growth will likely fall by half, to 1.7% from 3.5%, as monetary tightening and an expected slowdown in public spending kick in.

For the full note on the Bloomberg terminal, click here. The Best of Bloomberg Economics | - Trump announced members of his senior leadership team at the Treasury Department, including Ken Kies as assistant secretary for tax policy.

- Argentina is debating seeking new loans through either investment funds or the IMF, according to a senior government official.

- Turkey's inflation rate fell more than expected last month, potentially making it easier for the central bank to cut rate again.

- US mortgage rates moved up close to 7%, threatening to further squeeze buyers, with home-purchase applications dropping.

- Concerns over unexpectedly high food prices in Sweden have pulled Riksbank policymakers into a public row with the largest lobby group for the sector.

- UK taxes on minimum wage jobs will basically have doubled in a decade after the Labour government's payroll taxes come into effect, says a conservative group.

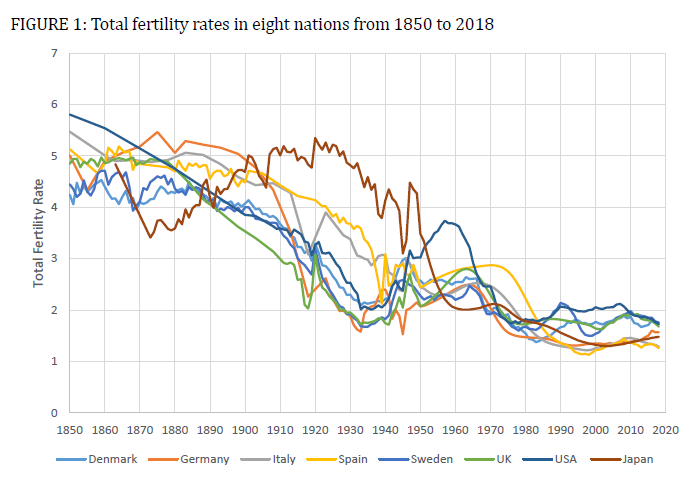

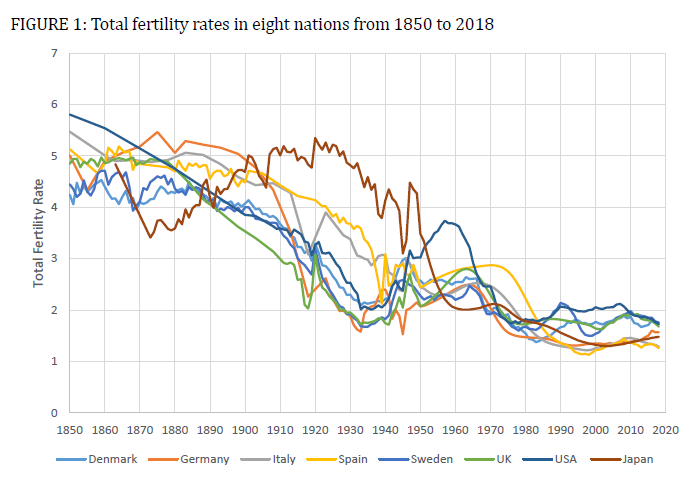

One of the big questions in demographics is why there's such a divide in fertility rates globally: East Asia and some European countries have seen steep declines while rates in some Western Europe and Scandinavian countries have been relatively stable. Nobel laureate Claudia Goldin — who was only the third woman ever to get the top prize in economics — adds one answer: economy clashing with tradition. Countries where fertility rates have plunged in recent decades (South Korea and Japan among them) also experienced rapid economic growth after the 1950s compared to peers. That gave women more freedom very quickly, but society — and men— haven't caught up to changing conditions. Goldin's quick to note it's not just about gross domestic product expansion, but also the transformation to a society with "developed markets, thicker communication networks, and denser settlements."  Source: Claudia Goldin "The reduction in fertility in the half century since the 1970s in most of the world, including the twelve nations just mentioned, has been astonishing," Goldin writes in a December research paper. "I hope to convince you that some part of the fertility decline in the past fifty years has had much to do with the macroeconomy in a long-run sense." |

No comments:

Post a Comment