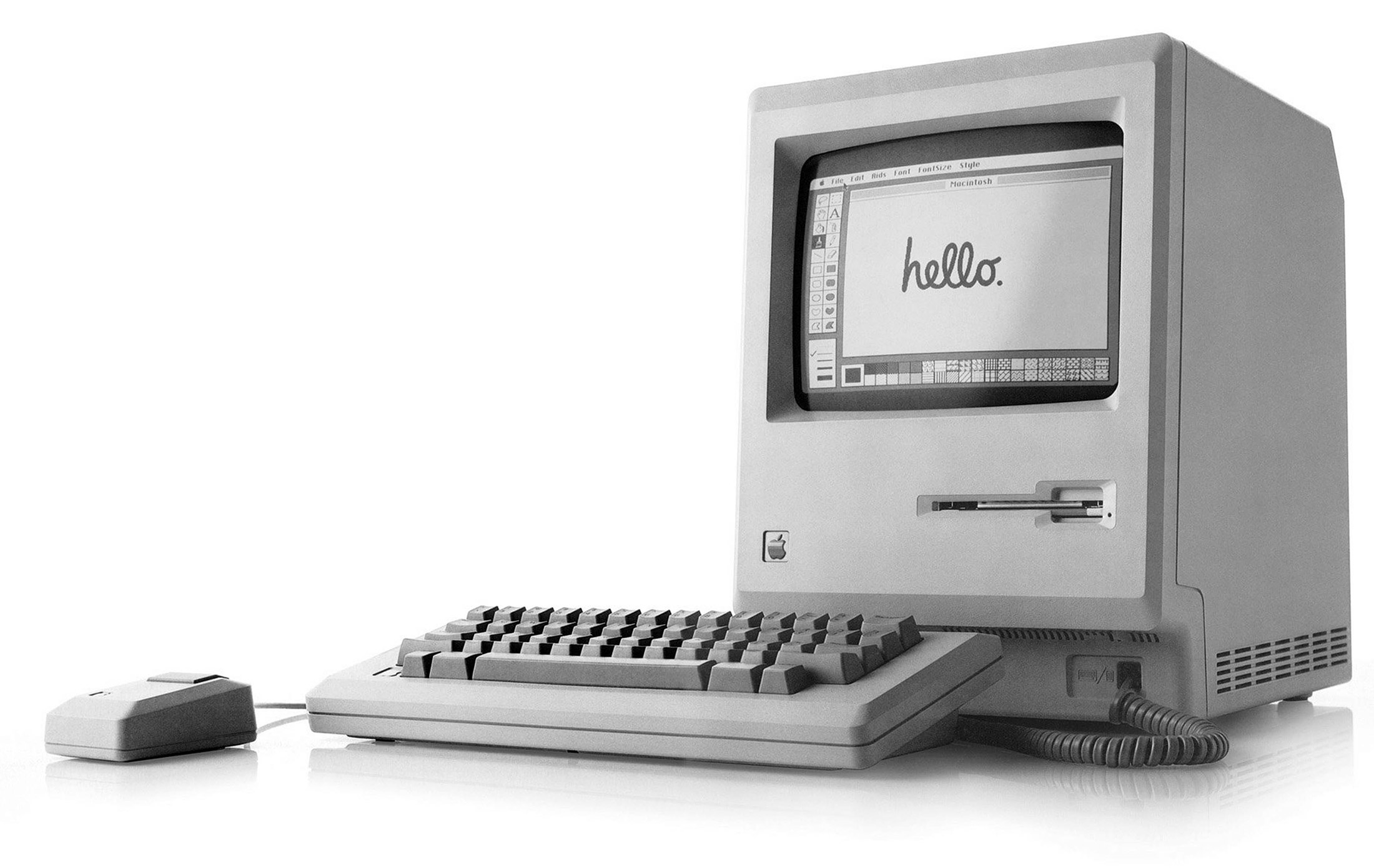

| If the early internet had a sound—aside from those screechy dial-up tones—it was the voice of AOL. Austin Carr writes about why today's AI products should consider harnessing its friendly vibe. Plus: What to expect as President-elect Donald Trump rolls out tariffs, and how high-tech tags could deter retail theft. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. Last week, amid all the election noise, a deeply influential voice in consumer technology died: Elwood Edwards. You likely don't recognize his name, but if you're above a certain age, you've heard his iconic expression: "You've got mail!" Back when America Online co-creator Steve Case was trying to popularize the internet portal, he turned to Edwards for help translating what was, in 1989, an incredibly novel concept for the masses. Edwards, who'd done voice-overs for radio commercials and whose wife happened to work for Case, ended up recording several phrases—a neighborly "Welcome" and "Goodbye" and a satisfying "File's done" notification—that spoke through the software to millions of AOL users in the coming years. It was a human comfort in an era of radical computerized change. The voice interactions sound quaint by today's standards, yet their emotional connection is exactly what so many new-age services, such as OpenAI's ChatGPT and Google's Gemini, struggle to replicate: warmth, dependability, productized nostalgia. In the 1990s, chatty postmen were no longer required to deliver electronic mail, but Case understood that to reach normies, the digitized exchange needed to be less robotic. Familiar interface icons of paper envelopes and front-yard mailboxes—a now-passé design approach called skeuomorphism—also helped sand off the future's scary edges. "It was disarmingly friendly, like the voice you'd expect from a stranger who offered to carry your grandmother's groceries," Case recalled in his book The Third Wave.  The original Apple Macintosh 128K computer, released on Jan. 24, 1984, by Steve Jobs. Photographer: Apic/Getty Images Humanizing tech, of course, wasn't a new idea. Steve Jobs grasped that making machines more user-friendly was key to making them mainstream, one reason he had the original Macintosh say "hello" to the audience at its 1984 introduction. Microsoft likewise relied on cute animations and dialogue suggestions to let Clippy demystify the complex menus of Word, while Amazon later infused its Alexa virtual assistant with charm and humor to ease concerns folks had about an always-listening device in their home. Still, it's hard to imagine anyone talking as tenderly about those products as Meg Ryan's character did of AOL in the 1998 Manhattan rom-com You've Got Mail: "I turn on my computer. I wait impatiently as it connects. I go online, and my breath catches in my chest until I hear three little words: You've got mail. I hear nothing. Not even a sound on the streets of New York, just the beating of my own heart. I have mail. From you." There's now a big debate about how much or whether human elements should be incorporated into artificial intelligence products such as ChatGPT or Tesla's Optimus robots. Part of this is for safety reasons: Serious AI guardrails are often necessary to protect a user's privacy and sense of reality. Too much anthropomorphizing can be dangerous, particularly as well-funded startups and colossal tech companies race toward artificial general intelligence without sufficient oversight and regulation. Then again, relistening to Edwards' intonations after all these years and realizing they still flood my ears with endorphins, I can't help but wonder what AI services would feel like if they had a touch more skeuomorphic humanity and a tad less prompt engineering. My heart, after all, doesn't skip a beat using Gmail's AI. Despite chatting with Microsoft's Copilot bot for months, I realized it doesn't even know my name. Meanwhile, ChatGPT's new voice companion, though mind-blowing, lacks a measure of soul. When I asked Maple—one of the voices OpenAI defines as "cheerful and candid"—what it does to make users comfortable in the same way as Edwards' greetings, it said its goal is always to be personable and engaging: "It's all about creating that welcoming vibe, much like AOL's classic phrases made people feel at home online back in the day." As long as its goal is to sound more like You've Got Mail than Her, I'm all ears. |

No comments:

Post a Comment