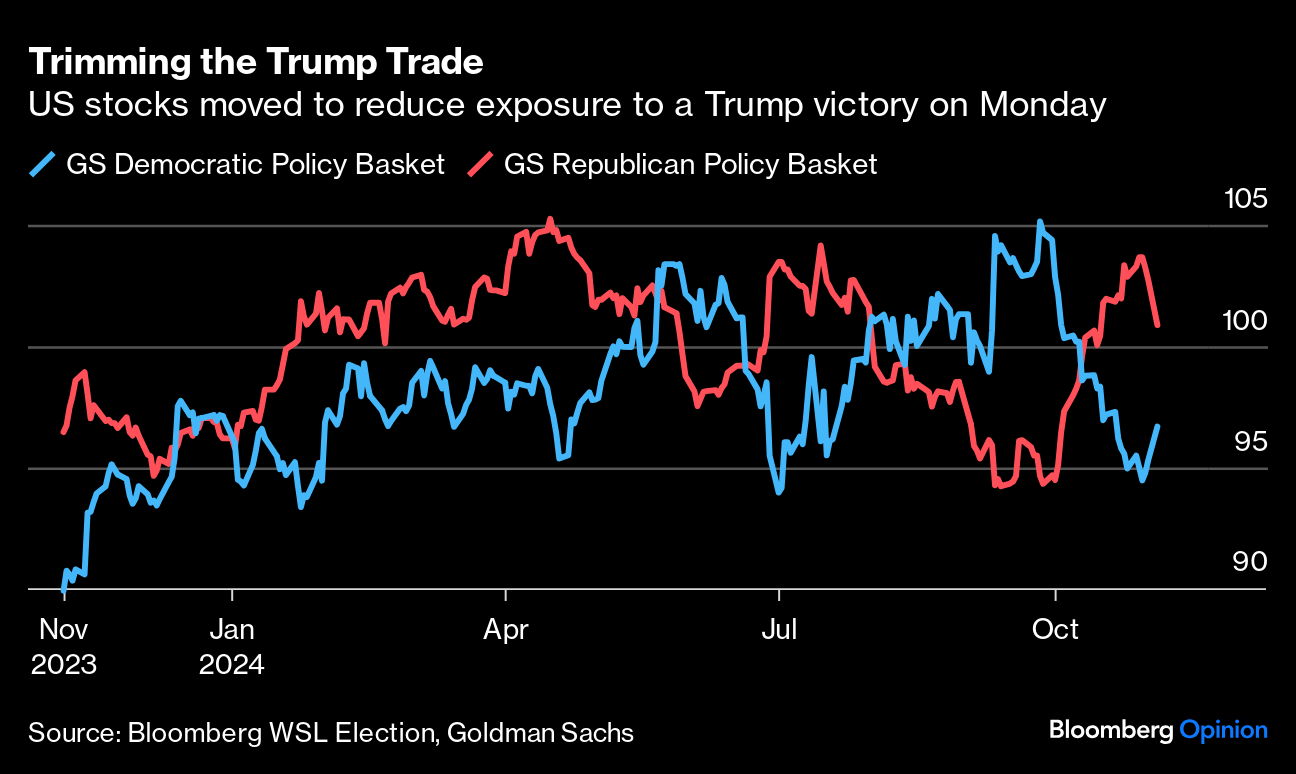

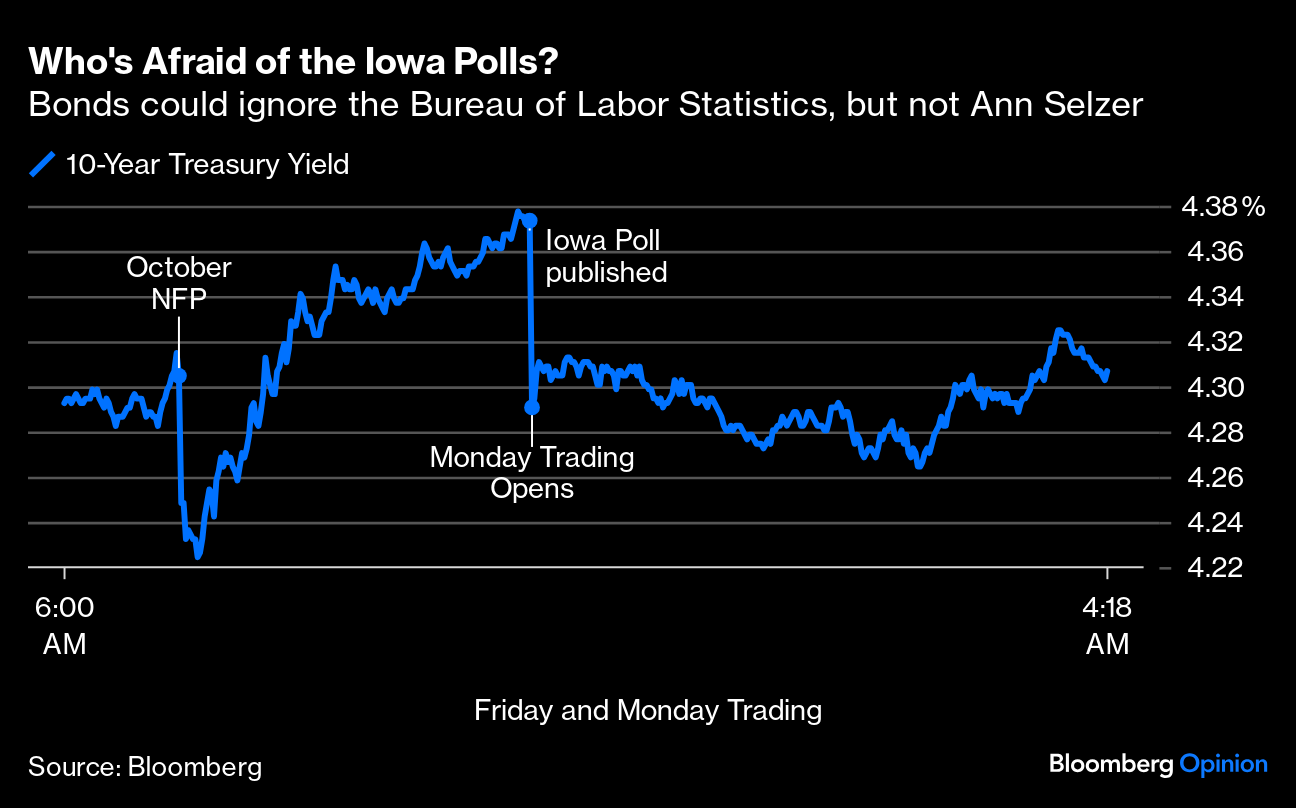

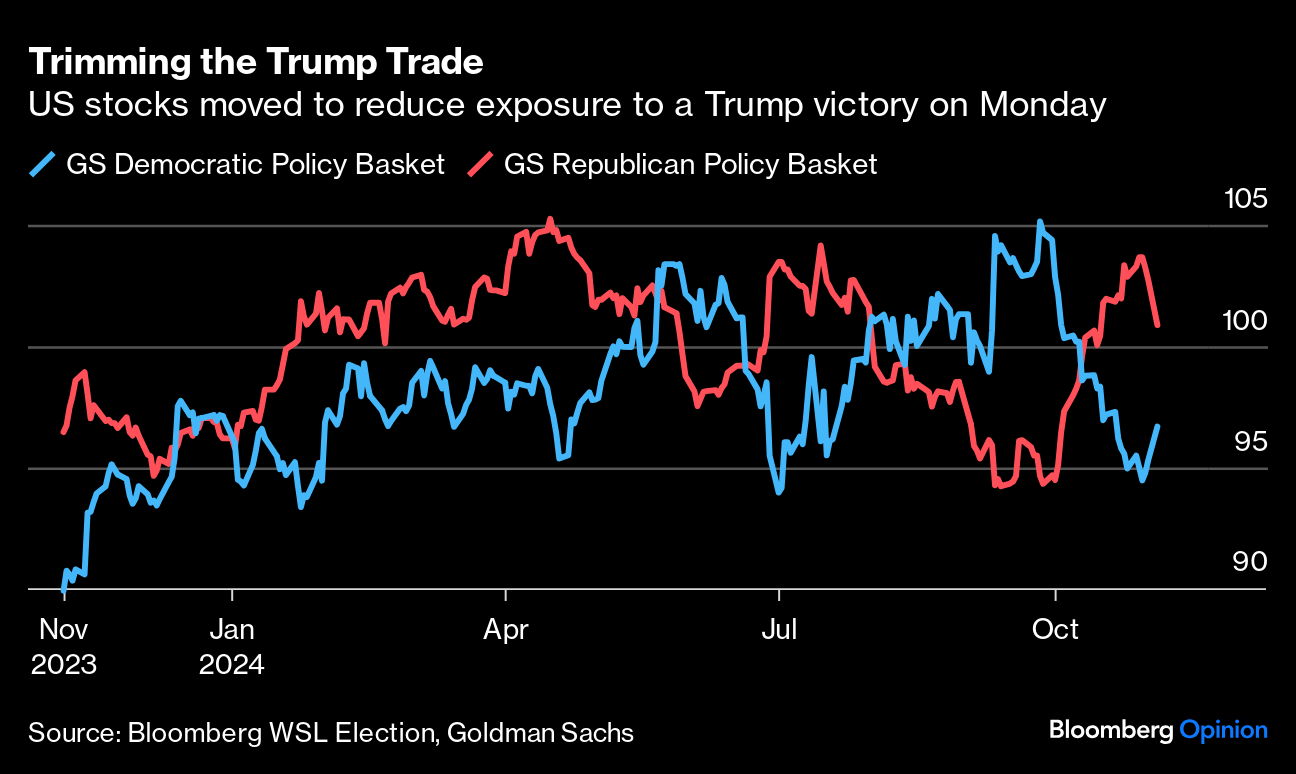

| The US is at last at the polls for an election that looms like the Twilight of the Gods. Also like a Wagner opera, it's featured immense amounts of sturm und drang, and seems interminable. Unlike Wagner, it's not at all clear who will win. After a month in which investors convinced themselves of the inevitability of Trump 2.0, the last few days have seen a rush to trim their positions. They're wise to do so, as few results at this point would be truly surprising. In the bond market, where yields would likely rise with a Donald Trump victory, and fall under Kamala Harris, the 10-year yield rose Friday despite very disappointing employment numbers. But all of that was lost at Monday's opening, thanks largely to an eye-catching poll by the much-respected Ann Selzer that showed Harris winning the red state of Iowa: The 10-year yield never got back to the low it hit immediately after Friday's jobs number, so this shouldn't be overstated. But the bond market plainly wanted to dial back its confidence in a Trump victory. The same was true with stocks, which can be analyzed using Goldman Sachs's baskets that pair companies likely to gain and lose under the policies of each candidate. The Republican basket surged through much of October, but fell sharply in Monday trading while the Democratic policy basket rallied:  This is a hasty recalibration, rather than a total reversal. Stocks near all-time highs and rising bond yields, hallmarks of "Trump trades," remain intact. Prediction markets mirror this, with Trump's chances on Polymarket, which has dominated attention since Elon Musk extolled it on X last month, as high as 59.1% (down from more than 66% last week). Others put his chances lower, but all still have him above 50%.

Such narrow odds imply that anything could happen: an easy victory either way, or a nail-biter. Beyond the obvious question of who wins the presidency, we also need to know whether there will be another destabilizing period like in 2000 or 2020 in which the result is contested. Control of the Senate (very likely to fall to the Republicans but not a certainty) and House (an almost exact 50-50) are also unlikely to clear up for a few days, and will determine what policies are possible. There are so many scenarios that there's little point going through likely market reactions to each one; this will be a question of staying calm and patient, while being on the alert for opportunities. For election night, prediction markets come into their own as results seep out; on the terminal you can do this at WS ELECNIGHT <GO>. To give you an idea of the likely highlights, there are handy guides from the New York Times, CNN, Slate and the BBC. It's also noticeable that the last few days have seen some key assumptions in the Trump narrative called into question. Polls underestimated him in 2016 and 2020, and so it's widely assumed that they're doing so again. That undergirded the steady increase in his perceived chances while Harris maintained a narrow lead in the polls — but in the last few days that assumption has come under question.

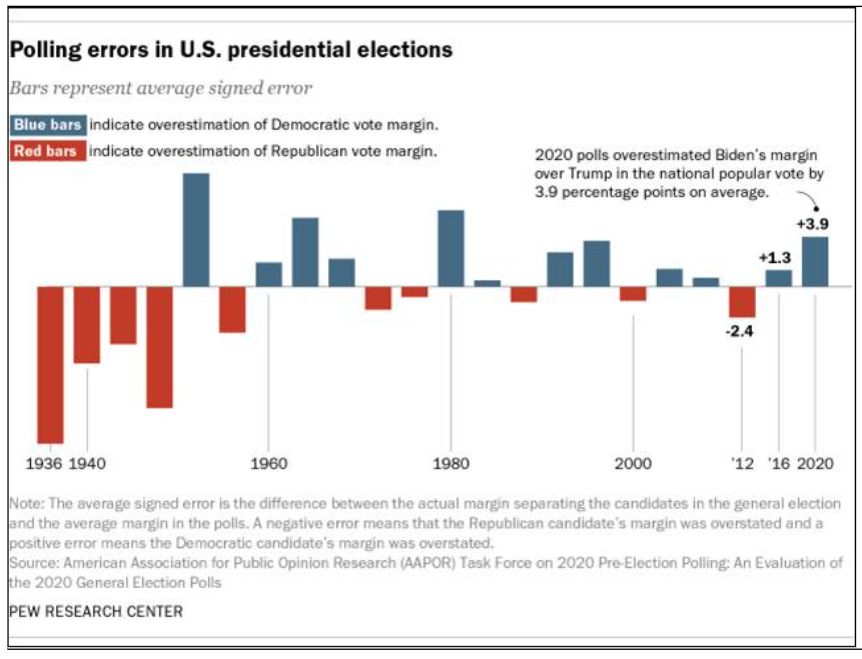

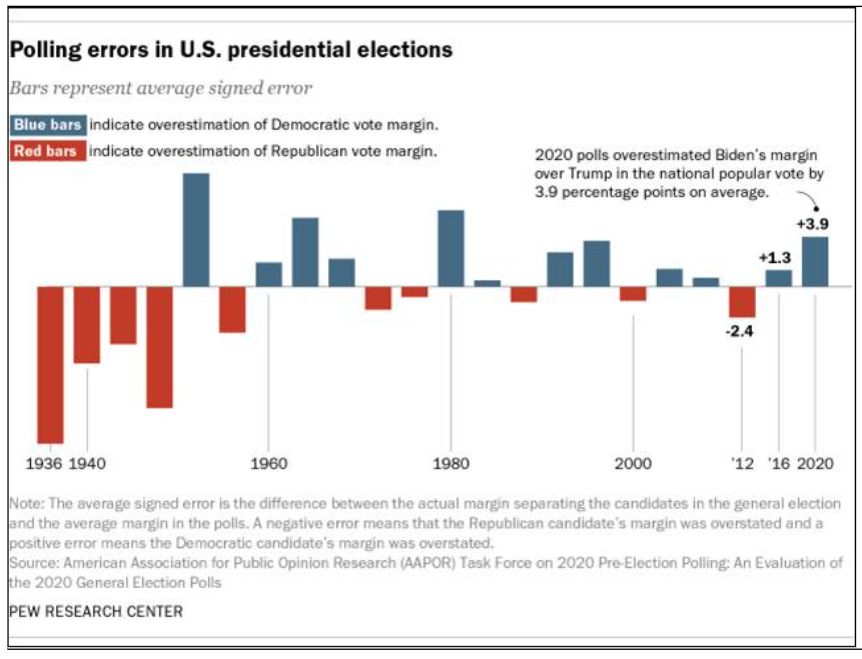

Brent Donnelly of Spectra Markets points out that over time, pollsters tend to revert to the mean. When they make a mistake in one election, their tendency is to adjust and over-compensate so that they err in the opposite direction. He offers this graphic from the Pew Research Center:  Pollsters are desperately trying not to undercount "shy Trump" voters as they did in 2016 and 2020. It's possible that this has led them instead to undercount women reluctant to admit that they've decided to vote for Harris. Nate Silver suggests that pollsters are subject to "herding" and are adjusting their results so as not to look too far out of line with everyone else. This is a common strategy among active investment managers, who want to avoid the embarrassing underperformance that prompts clients to take money elsewhere. It implies that both pollsters and markets might have tried too hard not to repeat the mistake of underestimating Trump. We'll know soon. Although maybe not that soon. According to futures traded on Kalshi, there is a one in three chance that The Associated Press won't be able to call the election either Tuesday or Wednesday. That wouldn't be good for volatility in the markets, or for anyone's sanity, and it would step up the risk of civil unrest. Buckle up, everyone. The efficacy of blockbuster weight-loss drugs has never been in doubt after they rose to prominence on the back of social media testimonials in the past four years. For investors, GLP-1s, with a cultural reach broader than any new drug since Viagra, have been a gold mine. However, the wave ridden by the likes of Novo Nordisk A/S and Eli Lilly and Co. is losing momentum. Lilly, which makes both Zepbound and the diabetes treatment Mounjaro (which is typically repurposed for losing weight), took a big hit last week after reporting disappointing sales. As it lowered its guidance, its shares fell nearly 10%, erasing almost $110 billion in market value. Denmark-based archrival Novo Nordisk, maker of appetite-blocking shot semaglutide, sold under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy, is down more than 25% since June:  How is this happening even when the total addressable market, expected to climb to $130 billion by 2030, is still rising? It's not as though obesity has gone away, unfortunately. This was the Lilly drugs' first sales miss, raising the question of whether the selloff was overkill or a sign of deeper problems. The company says that the shortfall arose from inventory issues, as wholesalers had heavy stocks at the end of the second quarter, leading to lower third-quarter sales. But Zepbound and Mounjaro were only recently removed from the US Food and Drug Administration's shortage list, so missing estimates by $900 million was startling. Bloomberg Intelligence's Sam Fazeli argues that the shortfall casts doubt on the storied demand: You're saying to me that demand cannot be satisfied. We're supply-limited. So, why is there an inventory issue in the middle here? And, of course, that's what led to the question of, oh my God, are we overestimating demand here? Is the company overestimating it? Is the world overestimating demand?

Lilly has a shot at redemption. It's still up nearly 40% this year, and the revision of its forward guidance is lower than the shortfall recorded. Fazeli argues that the company's dozen variants of the blockbuster drugs potentially offer additional income streams. On Wednesday it will be Novo's turn. Lilly's disappointment took a toll on the Danish company's share price, which has had a torrid time since peaking in June, but the prescription trends for its blockbusters look strong. Earlier this year, Wegovy was approved in the US for treating serious heart problems in obese and overweight adults, which should help push sales. Investors will look for clues on Novo's game plan. There's growing optimism that the next wave of growth in the obesity-treatment market will be through pills. Bloomberg News reports that Novo is developing a weight-loss pill that it hopes will help patients lose roughly as much weight as its Wegovy shot. Lilly is in advanced clinical trials for its oral drug, orforglipron; it produced an average loss of about 15% of body weight in 36 weeks when given daily to adults with obesity, according to a mid-stage study published last year. Viking Therapeutics Inc.'s obesity pill showed promising results in an early stage study. Pfizer Inc. and AstraZeneca also have pills in the works. The performance of an exchange-traded fund tracking obesity and cardiometabolic drug makers, up by about 10% this year, confirms that the sector is still alive. Novo and Lilly account for only 9% of the index on which it's based, which includes 44 other companies: With the initial burst of enthusiasm fading, investors are looking for new weight-loss drugs. Novo has hopes for its latest compound, cagrilintide, which it will combine with semaglutide. CagriSema aims to help patients lose at least 25% of their body weight. The company's scientists argue that it's possible the combo may help patients keep off lost weight even when they stop the drug. That sounds a little too good to be true, but if everything checks out, know that it's in trials and should hit the market sometime in 2026. — Richard Abbey While everyone braces for a political earthquake in the US, remember that tectonic plates are shifting elsewehere. For a generation, China has been an engine of perpetual growth, while deflation-mired Japan has provided everyone else with dirt-cheap finance. It's ever clearer that they're changing positions.

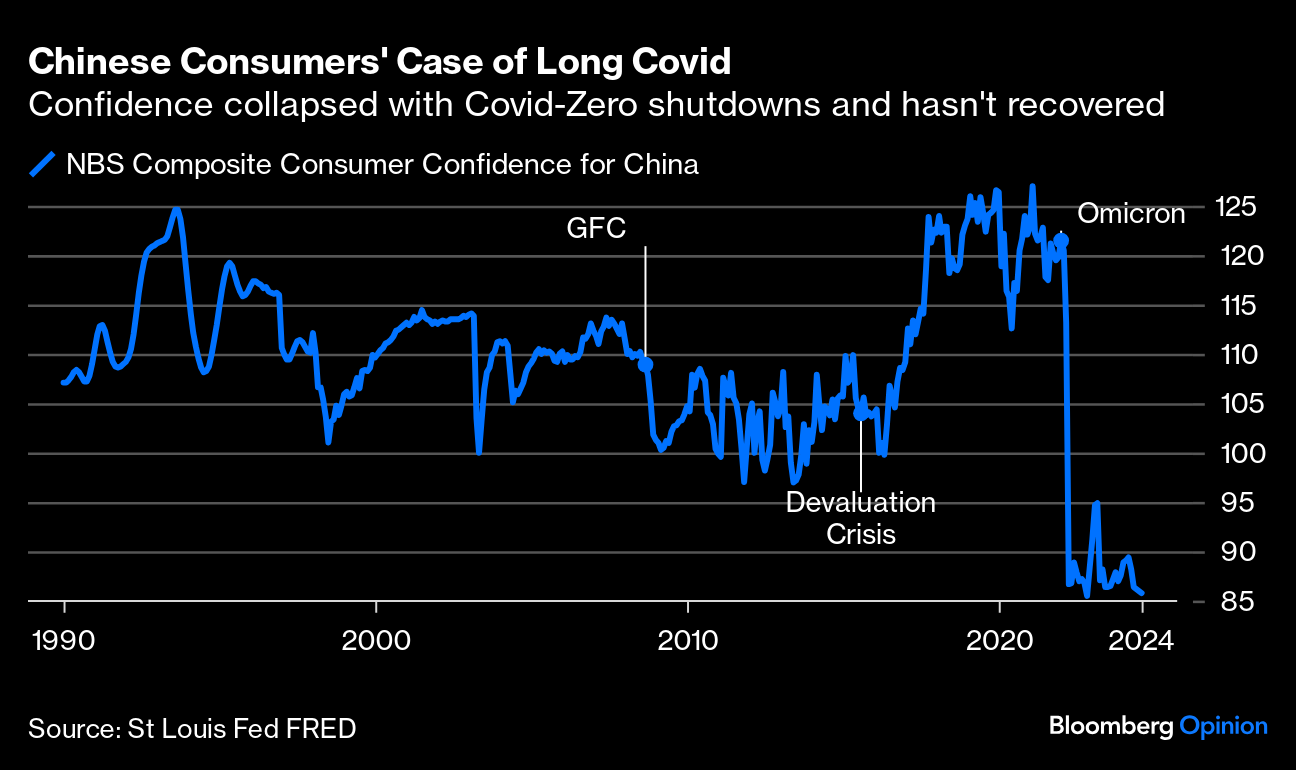

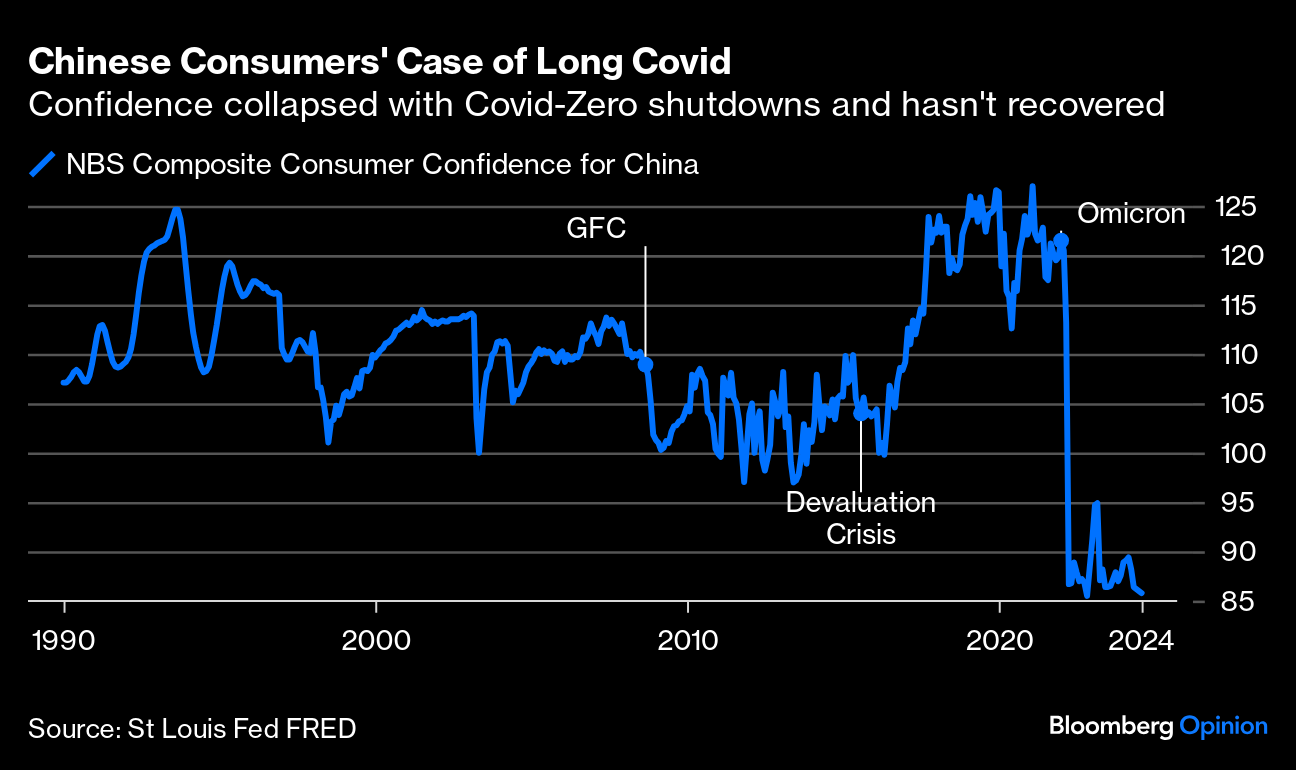

Jesper Koll, the veteran investment banker who now publishes the Japan Optimist newsletter on Substack, illustrates this convergence with the countries' 30-year government bond yields. Unlike other maturities, Japan's longest bonds are generally "free market," he says, and not subject to intervention from authorities, so this is meaningful. The lines have met:  The return of inflation to Japan led to an inconclusive general election last month, and very uncharacteristic political uncertainty that continues. It drove a sharp correction in the yen carry trade earlier this year. But Koll points out potential advantages for the rest of the world. Higher yields are good for life insurers and pension managers, as their liabilities become cheaper, particularly in a country where they've budgeted for an eternity of minimal yields. Koll suggests that there will soon be stories of over-funded Japanese institutions with money to spare, which they can deploy outside Japan. The country on the other side of the equation has much at stake in the election. China has long aimed to make the same transition as Japan, toward the domestic consumer and away from reliance on construction and exports. It looks as though consumer confidence is still on the floor after the harsh Covid-Zero shutdowns triggered by the omicron variant in late 2021. Don Rissmiller of Strategas Research Partners shows that the stimulus announced before the recent Golden Week holiday has had almost no effect:  This is a serious issue that could worsen with an intensification of trade hostilities. Don't forget about it. But for now, this comment from Donnelly of Spectra Markets captures all you need to know: None of this global macro stuff matters much right now. Yes, China has plugged the leaky bathtub, but they refuse to fill it. Yes, Europe is a bit less bad, but it's still bad. And all anyone cares about for now is the election. Good news is, we should know the US election outcome before the end of this year.

Election night 2020 happened in the middle of a pandemic. My favorite moment came when Arcade Fire premiered Generation A on Stephen Colbert. They were wearing masks and performing in someone's basement; just remember things could be worse!

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Timothy O'Brien: Trump Is Unfit for the White House. Don't Let Him Back In

- Mohamed El-Erian: The Two Things We Need From the Federal Reserve Right Now

- Shuli Ren: Where Saudi's MBS Beats China's Deng Xiaoping

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment