- It's been a golden millennium so far.

- Why has gold done so well? Take a look at how much money has been printed and borrowed.

- It's Germany's turn to raise political risks. European defense manufacturers are big beneficiaries.

- Wall Street isn't expecting much improvement from October CPI, but consumers are more upbeat.

- AND if you want something upbeat, try the Beat.

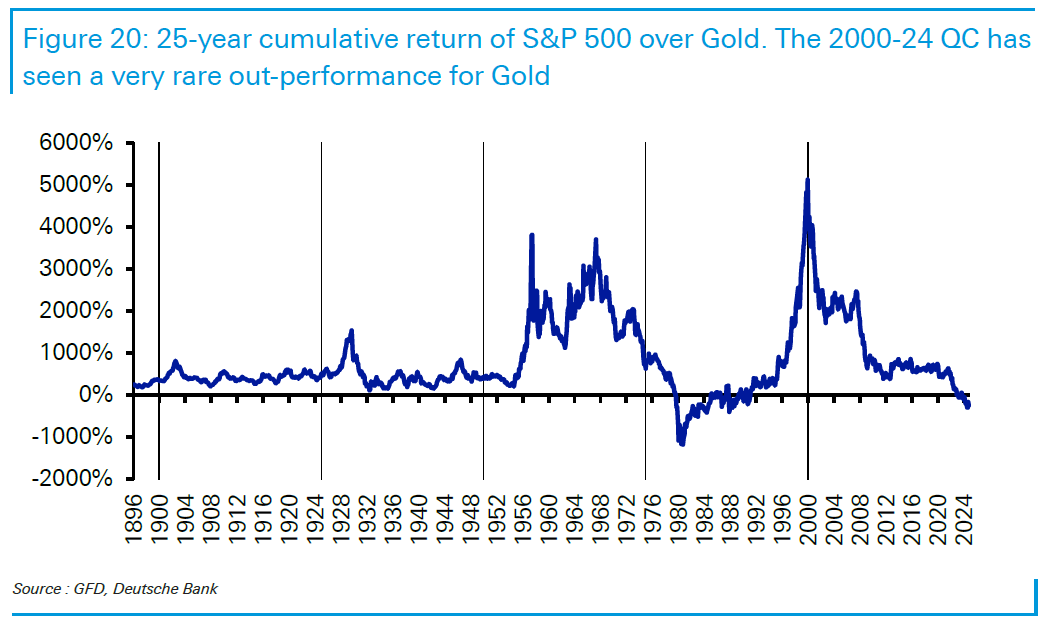

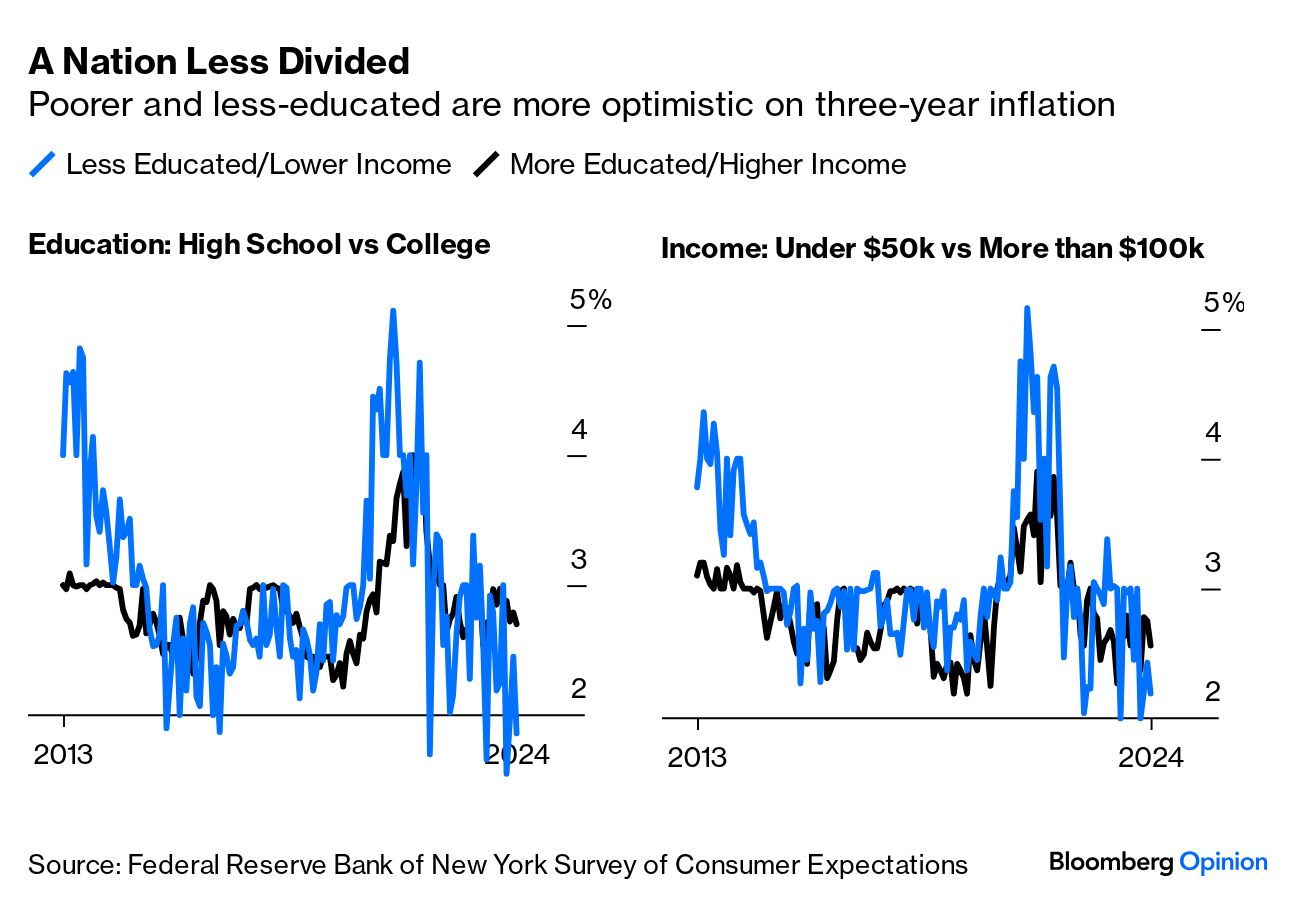

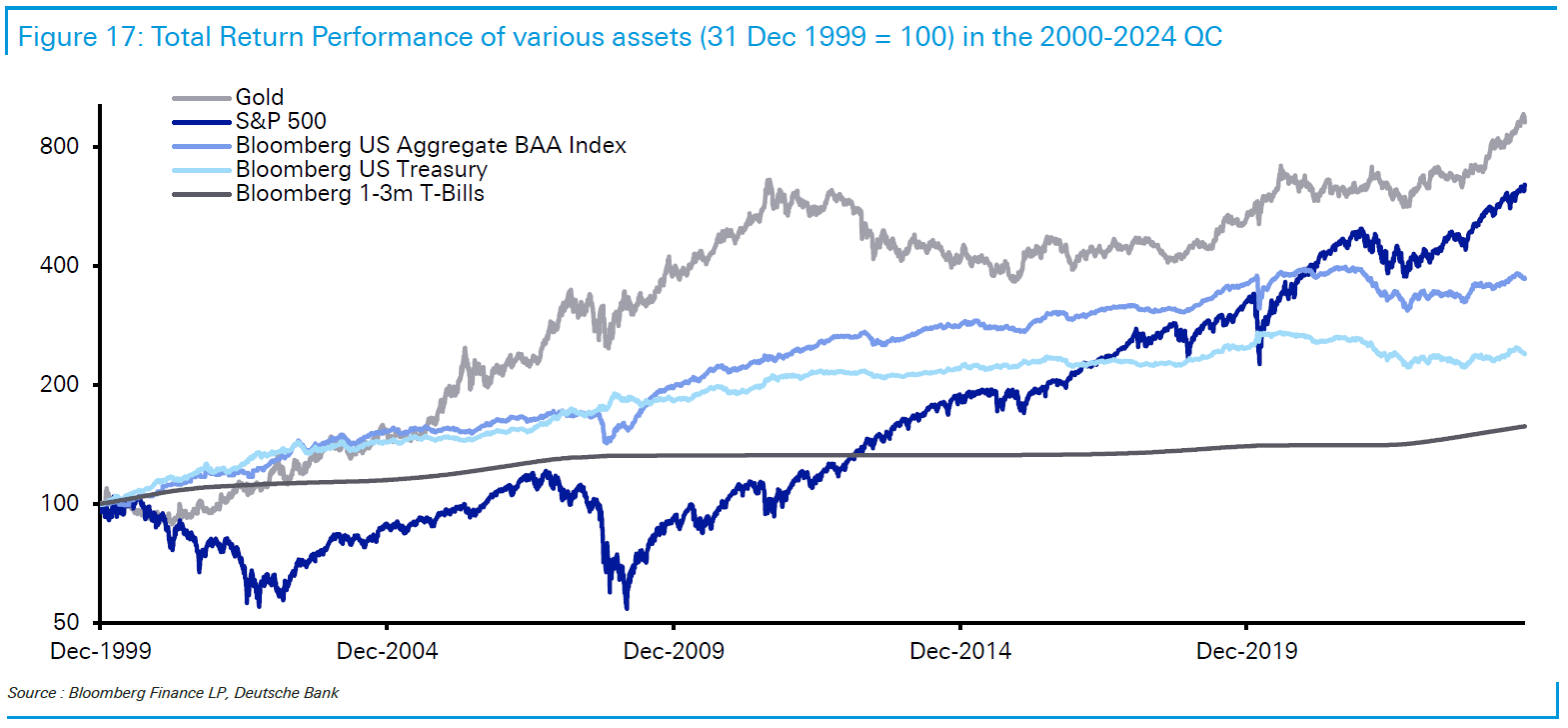

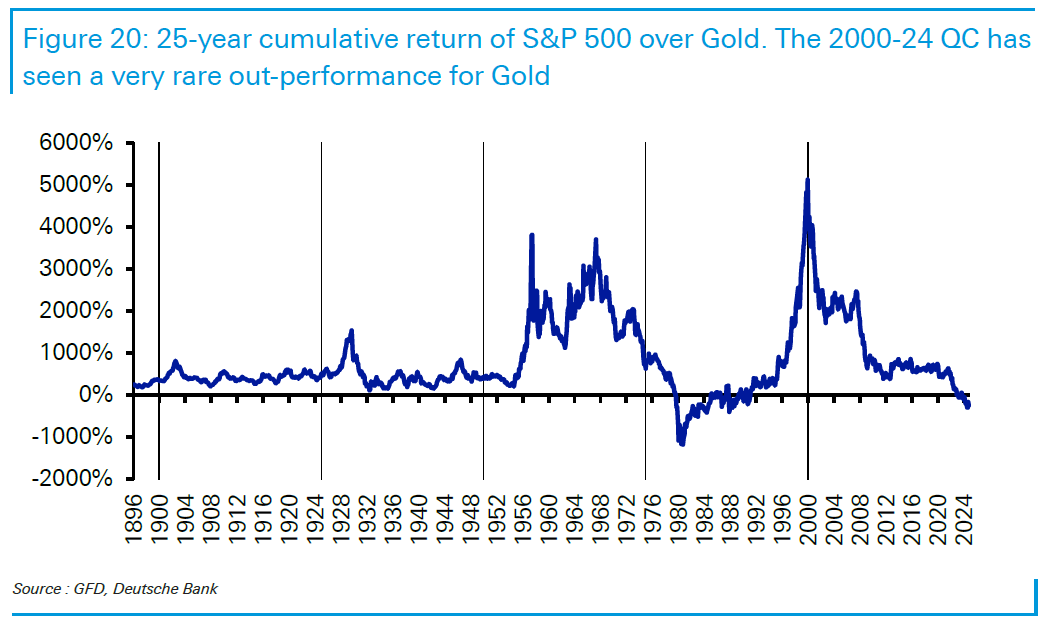

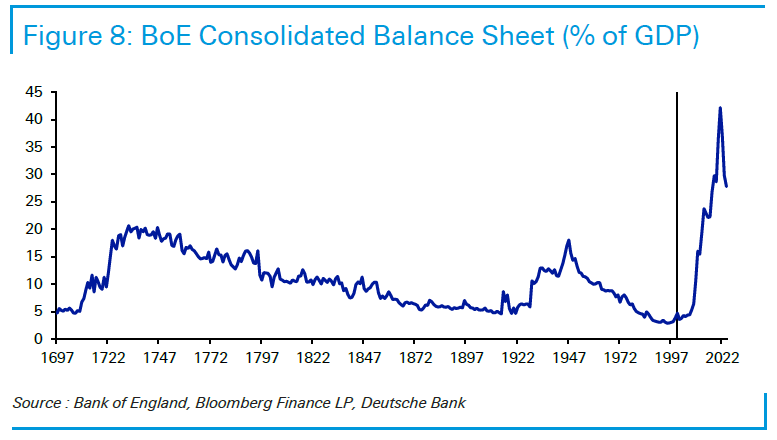

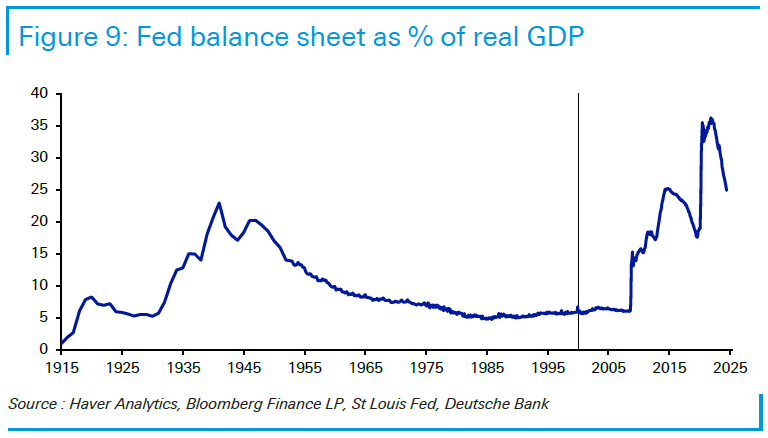

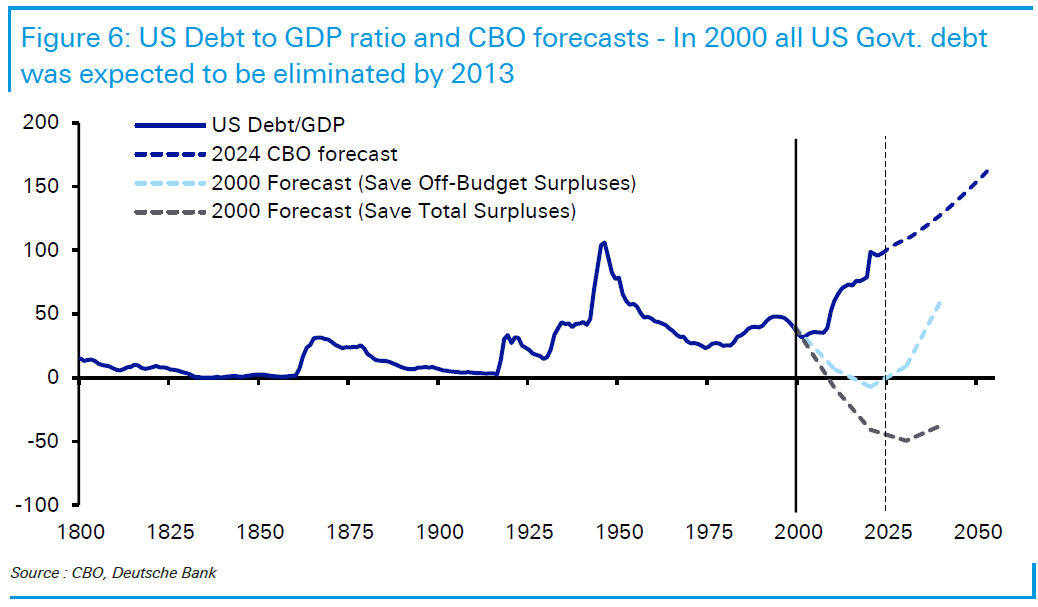

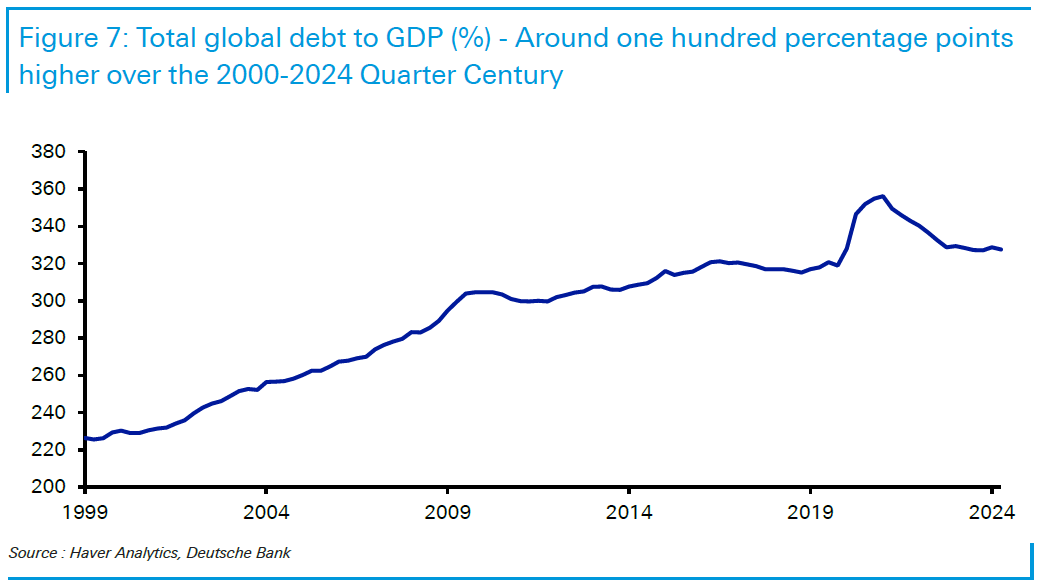

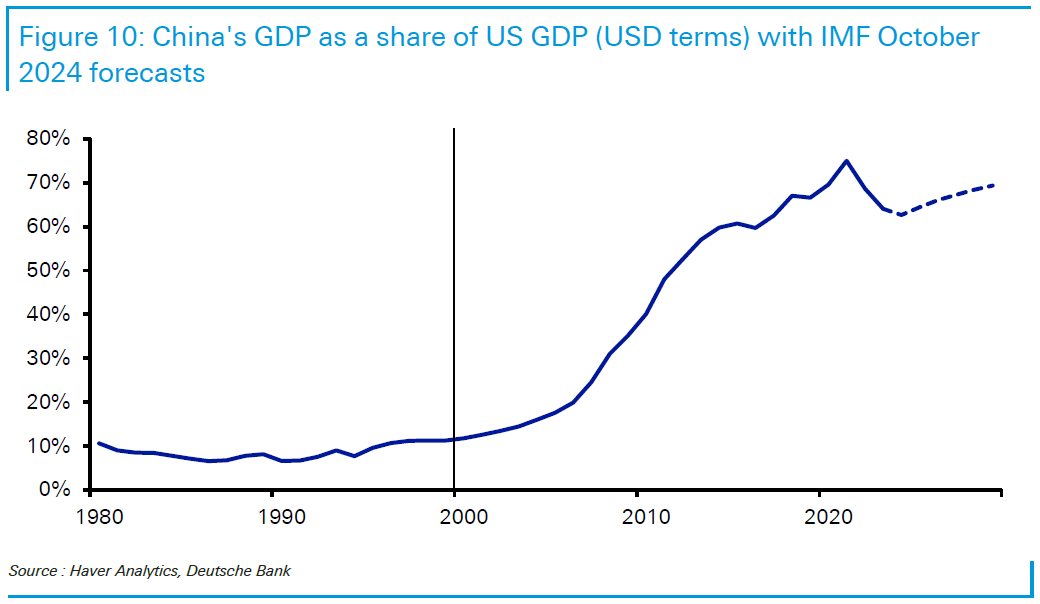

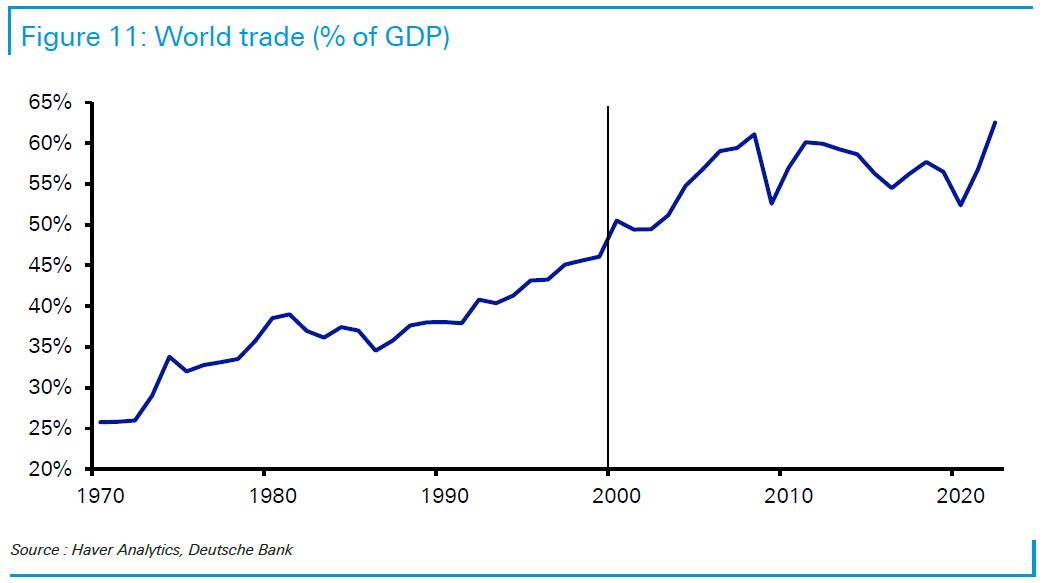

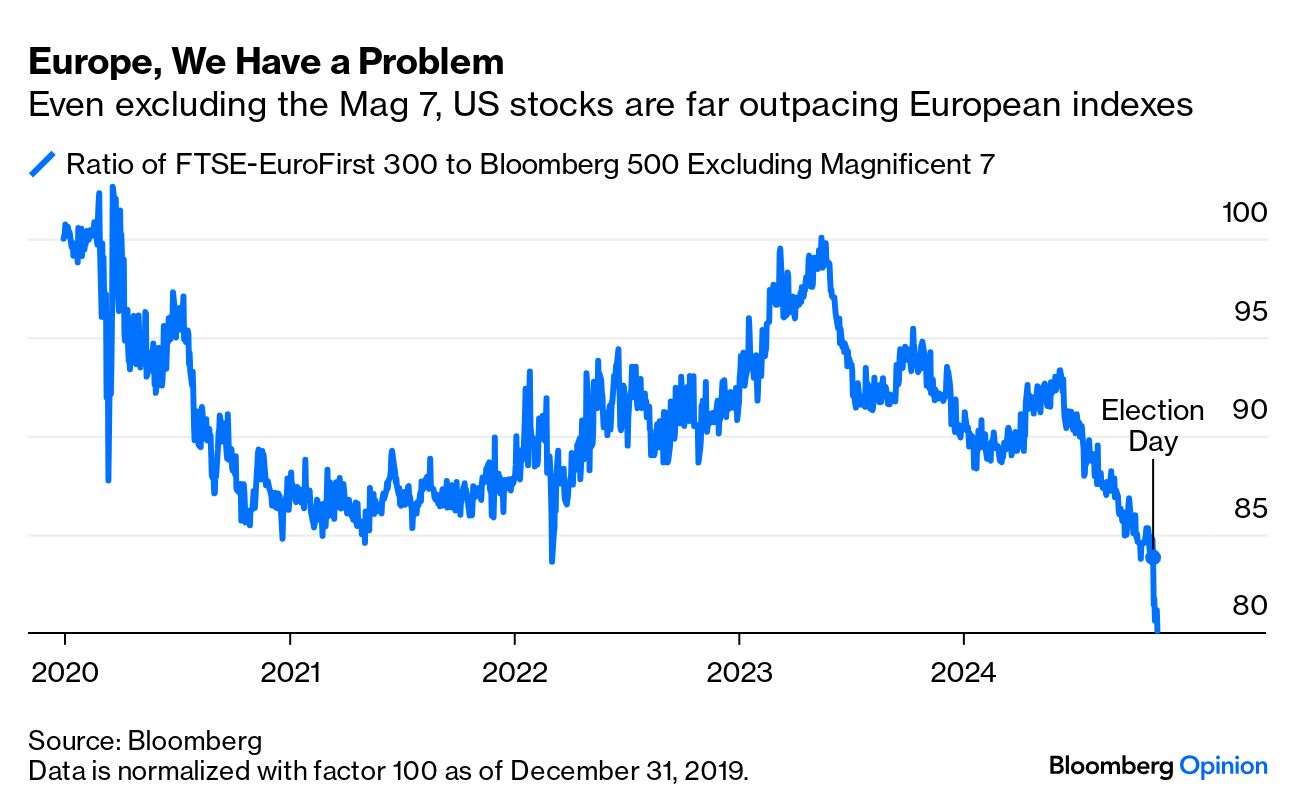

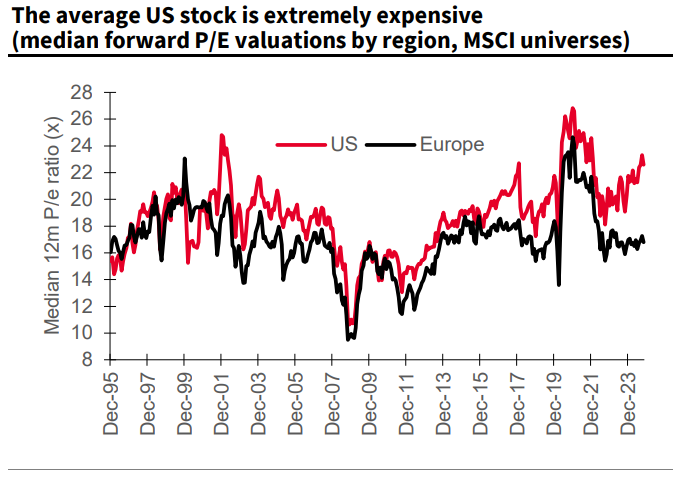

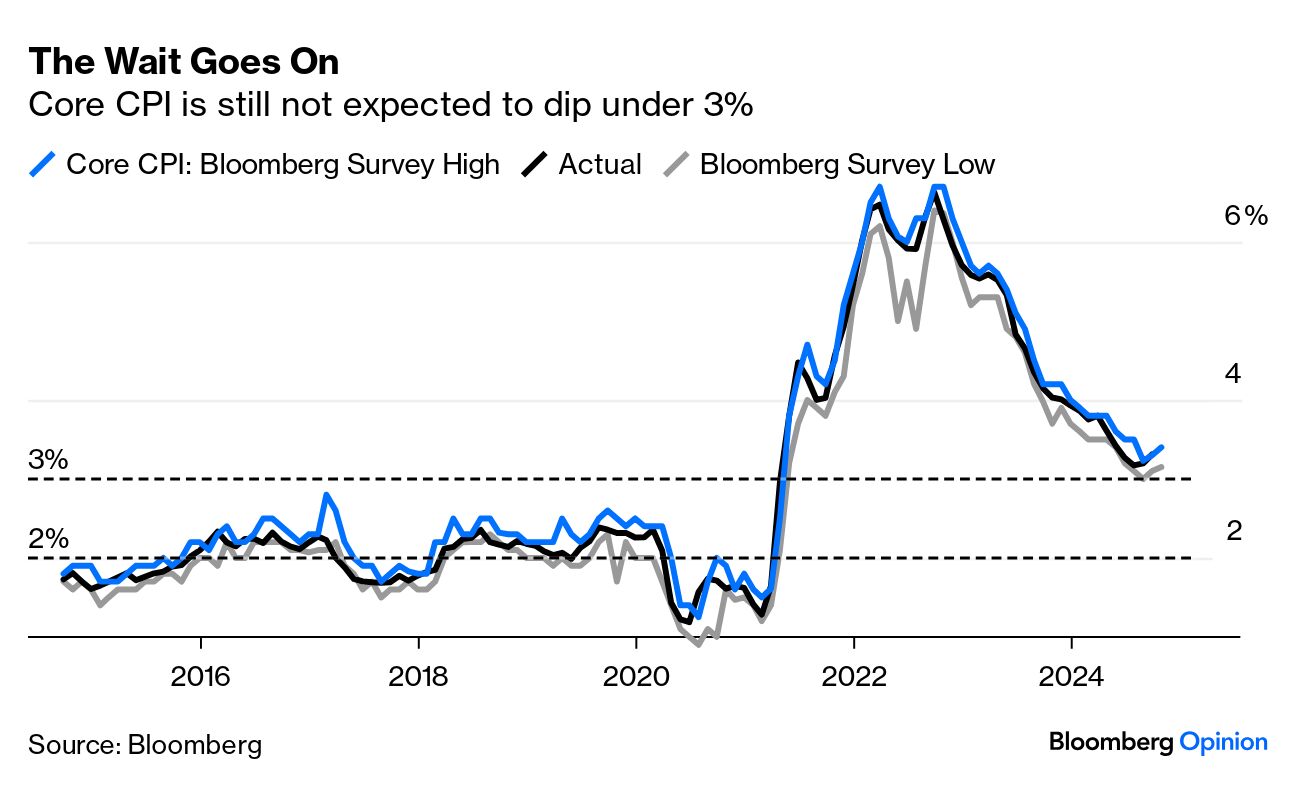

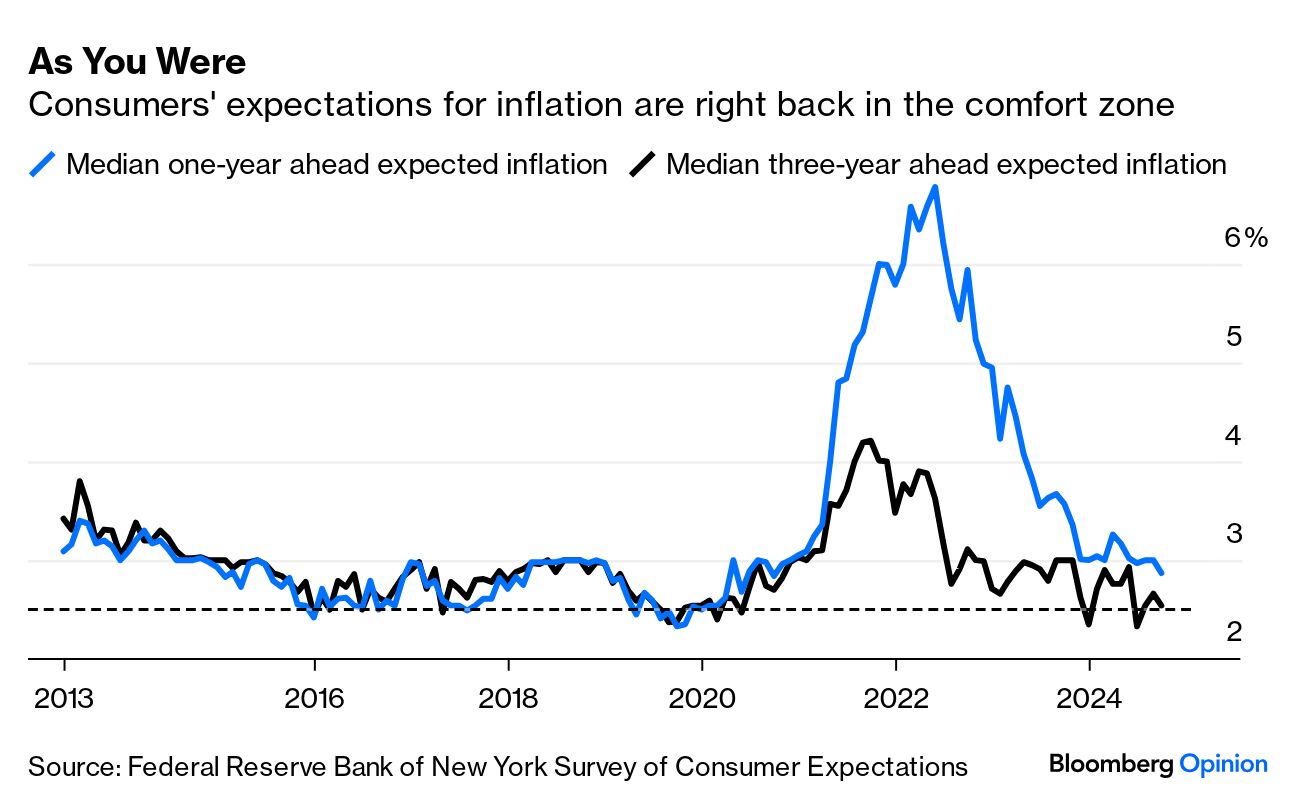

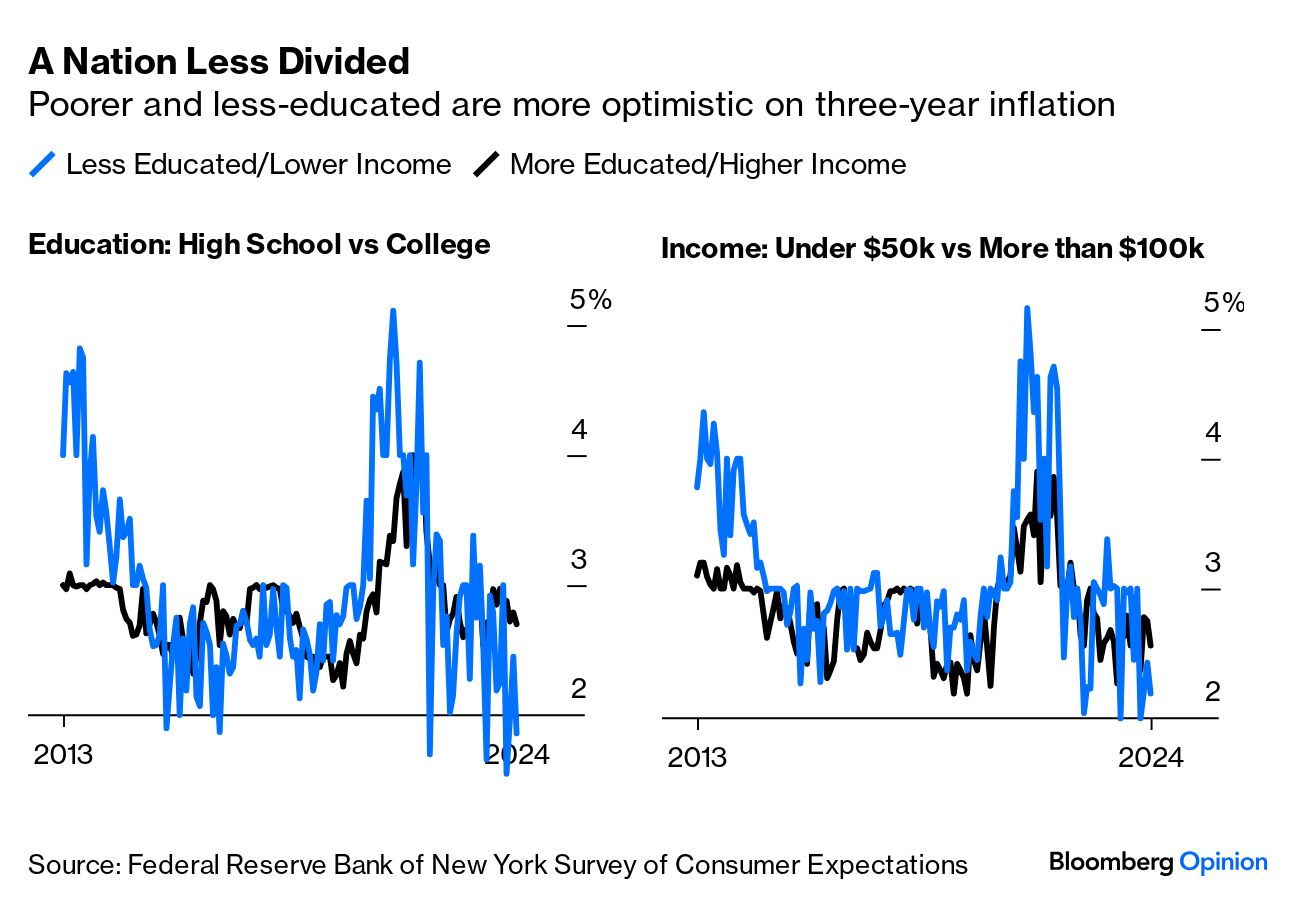

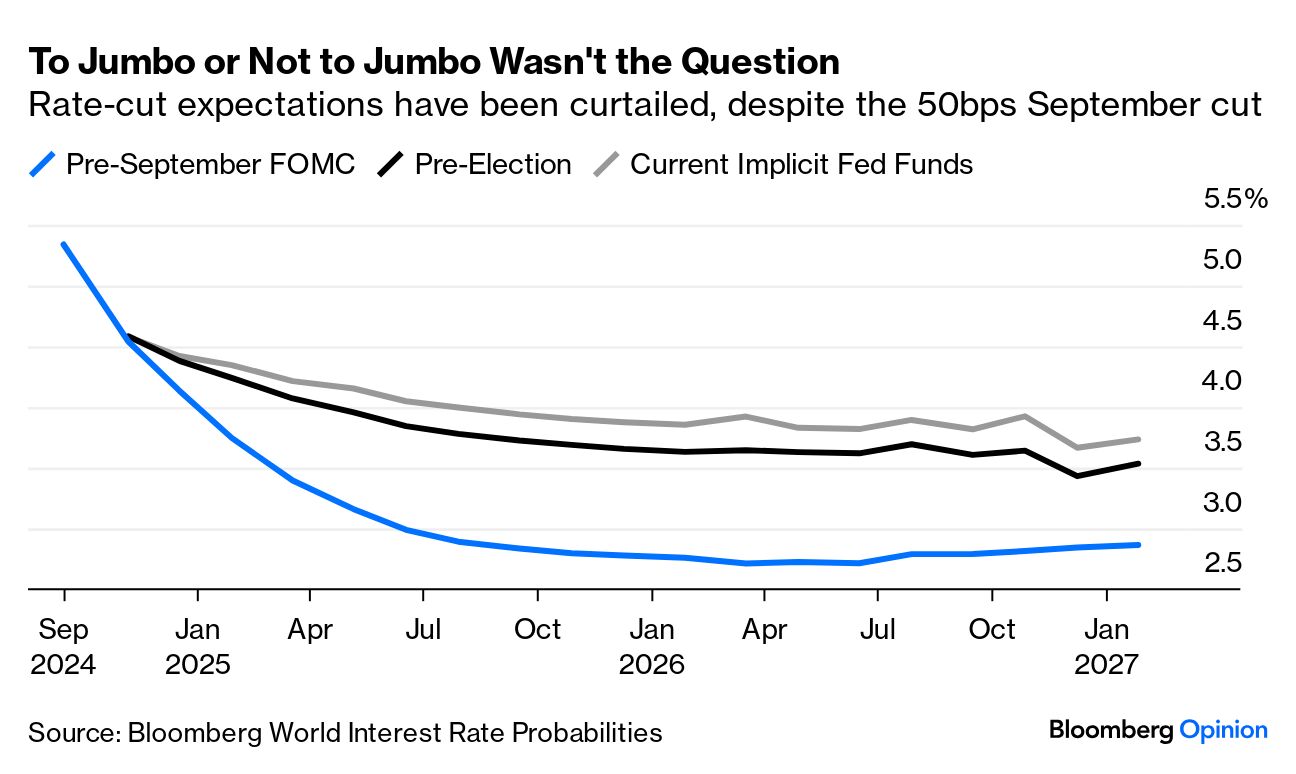

The third millennium (assuming it started in January 2000; remember Y2K?) is almost 25 years old. And it makes a sensible landmark on many levels for anyone trying to understand financial history. Jan. 1, 2000, marked almost the exact top of the biggest stock market bubble to date. Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia, nearly to the day. The euro had been initiated a year earlier. China joined the World Trade Organization a year later. The twin towers of the World Trade Center would stand for only another 20 months. And in today's polarized environment in the US, it's handy that Democrats have been in power for 13 of the years and the Republicans for 12, so generalizations aren't making a political point. All this creates a great juncture for Jim Reid, Deutsche Bank AG's resident financial historian, to make a fascinating study of the century's financial returns so far. (The charts are from him.) To start, the fact that the millennium opened with stocks historically strong means that they haven't had that great a quarter-century. Gold leads everything else: This isn't just a trick of the starting point. When Reid takes a look at the longer history of the ratio of the S&P 500 to the gold price (or what the S&P would notionally be worth if it were denominated in gold rather than dollars), he reveals a marked trend. The story of the last 25 years has been the steady advance of gold. By this ratio, the only time in history that is comparable is 1980, when the inflation that followed the end of the Bretton Woods gold peg led to an all-time low. That milestone proved to be a signal that the old order couldn't work, and we witnessed the growth of globalized finance underpinned by a Federal Reserve that determinedly stamped out inflation:  This does seem startling, given how well stocks have performed for the last 15 years. To understand the conditions that have favored gold, Reid's extraordinary data on central bank balance sheets offers an explanation. There are numbers on the Bank of England's balance sheet dating back to 1697. Since 2000, it has expanded in a manner that would previously have seemed impossible. Largely the same can be said for the Fed, even if it's only been around since 1915: Not only monetary policy went into overdrive. Fiscal policy has come as a very unpleasant surprise. At the beginning of 2000, the Clinton administration succeeded in eliminating the ongoing deficit, and there were plans to retire all US debt. That didn't happen. At present, US government debt as a proportion of gross domestic product is almost as high as when the country was on a war footing in the 1940s, and is projected to go much higher: The US and its Treasury market matter far beyond American shores, but the trend is worldwide. At the turn of the century, global debt was a bit more than double GDP. It's now somewhat more than triple: It can be irritating to hear pundits hyperventilating about risks of disaster and the unsafe foundations of finance, but there are reasons why they do. We don't know how this story ends, but anyone shown these figures 25 years ago would have been horrified, and predicted very serious trouble. Beyond the rise of global debt and printed money, the other most startling development has been the rise of China. Deng Xiaoping's effort to open the Chinese economy and prioritize growth was already almost a decade old at the millennium, but the model was just beginning to get into gear. Accession to the WTO would make a difference. This is what has happened to China's GDP as a share of the US economy since 1980: China has managed to keep growing even though globalization, as measured by trade volumes, has stalled; roughly ever since the 2008 financial crisis. International trade had been one of the presiding trends of the 1990s, taking off after the Berlin Wall fell. It hasn't gone into reverse, (though that's a strong possibility with a new wave of Trump tariffs), but appears to have reached its limit: There is very much more where these figures came from, including some alternative calculations starting from 1995 rather than 2000 to avoid the uniquely bad starting point for stocks. It waters down the findings somewhat, but still makes the current period look rather disappointing. All of this news, however, should be in the price. What really matters is what happens next. One of the classic texts in finance is Triumph of the Optimists by the academics Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, a massive study of asset class performance in the 20th century across the globe. It gets its title from stocks' fantastic showing from 1950 to 2000 — which happened largely because the optimists, from the standpoint of 1950, were proved right. The postwar miracles in Germany and China, the fall of the Soviet bloc, the rise of the Asian Tiger economies and then China all lay ahead. People in 1950 would have been glad just to know that nuclear weapons would not be used again that century. As a result, optimism triumphed; it was a great idea to buy stocks in 1950. In 2000, we now know, it was a better idea to buy gold. Compared to the reasonable rosy hopes of the time, it's the pessimists who have won. Those invested in stocks have done well, but largely because of the extraordinary increases in government borrowing and lenient monetary policy. It looks once more as though a concerted attempt to change the world's economic model and fix what isn't working is now underway. Let's hope the next 25 years are another victory for the optimists. It's hard to avert your gaze from the extraordinary post-election market moves in the US, but the clearest (negative) impact is being felt in Europe. Underperformance has been a fact of life there for a while (in part, as Reid shows, because the European Union has been increasingly displaced by China in global trade). It's gone into overdrive since the election. The Magnificent Seven technology platforms can distort the picture in America's favor. The depth of the loss of confidence in Europe grows clearest when we compare the FTSE-EuroFirst 300 broad large-cap index with Bloomberg's index of the 500 biggest US stocks excluding the seven: What's gone wrong? Valuation is a big chunk of it, and again this is not just a question of the lavish multiples currently being slapped on Big Tech. The following chart from Societe Generale SA's chief quantitative analyst Andrew Lapthorne controls for this by taking the median valuation for the US and Europe. US valuations have leapt forward again in the last two years, while Europe's haven't: This ought to offer some kind of opportunity. The US looks overdone (even more so with the post-election rally). But Lapthorne's chart shows that European valuations weren't driven down in any significant way before the election. And now, political uncertainty gives a reason to be nervous. Germany goes to the polls in February, three years after the invasion of Ukraine. The election looks very likely to usher the center-right Christian Democratic Union back into power, but the rise of more populist far-right parties adds significant unpredictability. Germany's political problems could have a radical effect on the international balance of power, as the voices opposing further aid to the Ukrainian war effort appear to be growing louder. Meanwhile, the return of Trump has raised concerns about the future of NATO, and intensifies the belief that European governments are going to have to spend much more on defense. Within the European market, the one-two punch from first Putin and now Trump has helped create at least one clear relative winner — the defense sector: It's always possible that the dangers currently confronting the continent don't come to pass, in which case it will present a great opportunity. But the risks have to be beaten first. Soon after you read this, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will publish consumer price inflation numbers for October. It will no longer affect the election, and it's not Donald Trump's fault. Henceforward it will, however, be his problem. The issue that sank his predecessor now looms as the biggest threat to completing his economic agenda. Median expectations ahead of publication are that core CPI (excluding food and energy) will be unchanged at 3.3% — still maddeningly at the 3% upper range of the Fed's target — and there's a significant body of opinion that it could rise: The Fed prefers the Personal Consumption Expenditures measure of inflation, which doesn't look quite so bad. As political commentary has emphasized time and again, the core figure may capture what central bankers might realistically hope to control, but not what they can buy. One piece of good news for them and incoming politicians alike is that consumer expectations for inflation appear to have come clearly under control. The New York Fed produces a monthly series on consumers' expected inflation over the next one and three years. Both have now dropped blow 3%. The huge spike in expectations, which should have been a clear indicator of trouble ahead in 2021, is over. These figures were taken before the election, so this is not just about optimism that Trump can fix it: On an interesting political sidenote — America's educational divide, and the gap between economic haves and have-nots, no longer shows up in this report. That's a positive sign. During the worst of the inflation scare, those with high school education or less expected worse inflation than college graduates. They're now more optimistic. Similarly, those on incomes of less than $50,000 per year used to be braced for worse inflation; they're now more optimistic:  But if consumer expectations are encouraging, the shift in expectations for the Fed is more concerning. This is not primarily about the election, although Trump's victory has helped continue a pre-existing trend. Before the "jumbo" 50-basis-point cut in September, fed funds futures implied that policy rates would dip well below 3% by the end of next year. That's shifted upward sharply, a process that has continued since the election. Jumbo or no jumbo, the market now works on the assumption that the Fed might not even cut as far as 4%: Therefore, this election result has only accentuated a trend that was already in place. There's nothing like a new download of inflation data to halt such a trend, or potentially to set it moving even more strongly. Get ready. Some of you might be in need of upbeat songs. For some reason, I've been listening to Sole Salvation by The Beat (known as The English Beat in the US) on repeat for the last two days. To my fury, I can't find a live performance anywhere on the web, but I did find this audio of a John Peel session. It's really, really upbeat. Any more suggestions out there?

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment