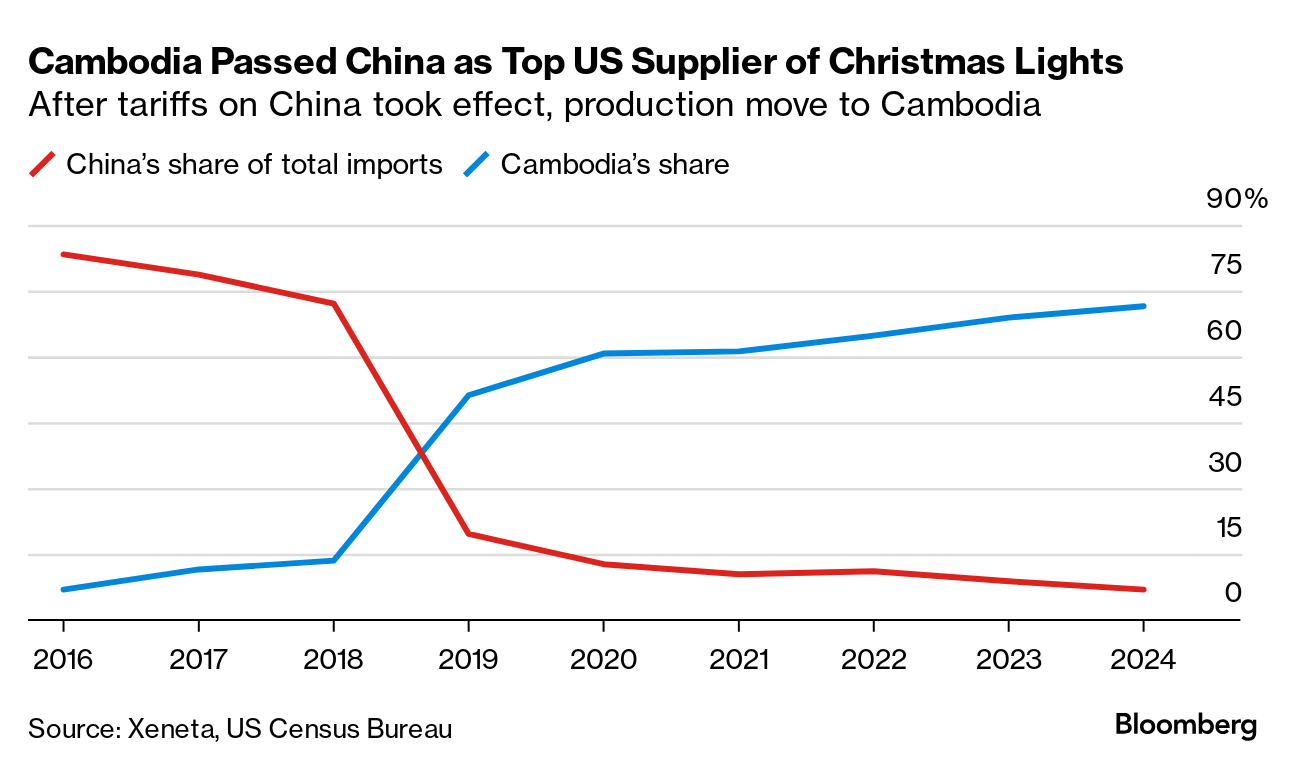

| Next time you see Christmas lights, consider the lessons they can teach about trade wars of the past and future. Before then-President Donald Trump increased tariffs in 2018 on US imports including Christmas lights, China was by far the biggest source of the more than $500 million in annual shipments of the holiday illuminants. After the tariffs, Cambodia rose to the top spot as Chinese producers found ways around the higher duties, according to US Census data compiled by Xeneta, an Oslo-based freight analytics platform. It was a remarkable shift: The US did about $560 billion in total merchandise trade with China in 2018, and less than $6 billion with Cambodia. A few key things are unclear in the case of Christmas lights that Xeneta analyzed, like whether the production actually moved from China or whether the goods were merely diverted and then packaged in Cambodia by Chinese affiliates. What it does illustrate is that tariffs don't always repatriate manufacturing jobs. But it also shows that some early Trump's tariffs had an speedy impact on certain items: The country of origin of a product as basic and cheap to make as Christmas lights can move quickly, originating mostly from China one holiday season and Cambodia the next. Read More: Macron Warns Europe Is Hurtling Toward Tariff War With US, China Fast forward to Trump's campaign pledges in 2024 and his plan for a much broader use of tariffs — 60% on everything from China, and 10% to 20% on all other imports — makes for a much messier, less predictable future for those trying to avoid the promised barrage of higher import taxes. "Last time you had to wait until a list was published and you'd usually have a couple of months before those tariffs were then implemented. So you had a little bit of time to frontload," Xeneta analyst Emily Stausbøll said. "This sudden shift that we saw with the Christmas lights from one year to the next is just not feasible on a huge scale." Read More: UK Officials Warn Government of Hurdles Facing Trump Trade Deal For one thing, near-shoring calculations are going to need refinement in a world threatened with universal US tariffs, where friend-shoring magnets for investment like Mexico might not be spared this time. Stausbøll said she recently talked with a freight forwarder in Mexico about the issue of auto exports, and he said "this throws a complete wrench in it because the investments he'd been talking about suddenly don't make sense anymore." In the short term, that means importers are frontloading shipments to avoid future tariffs (and a port strike in the US). Over the longer term, they're having to rethink where they're going to produce goods if everything is going to have a higher tariff. "This time it's going to be different," Stausbøll said. —Brendan Murray in London Click here for more of Bloomberg.com's most-read stories about trade, supply chains and shipping. |

No comments:

Post a Comment