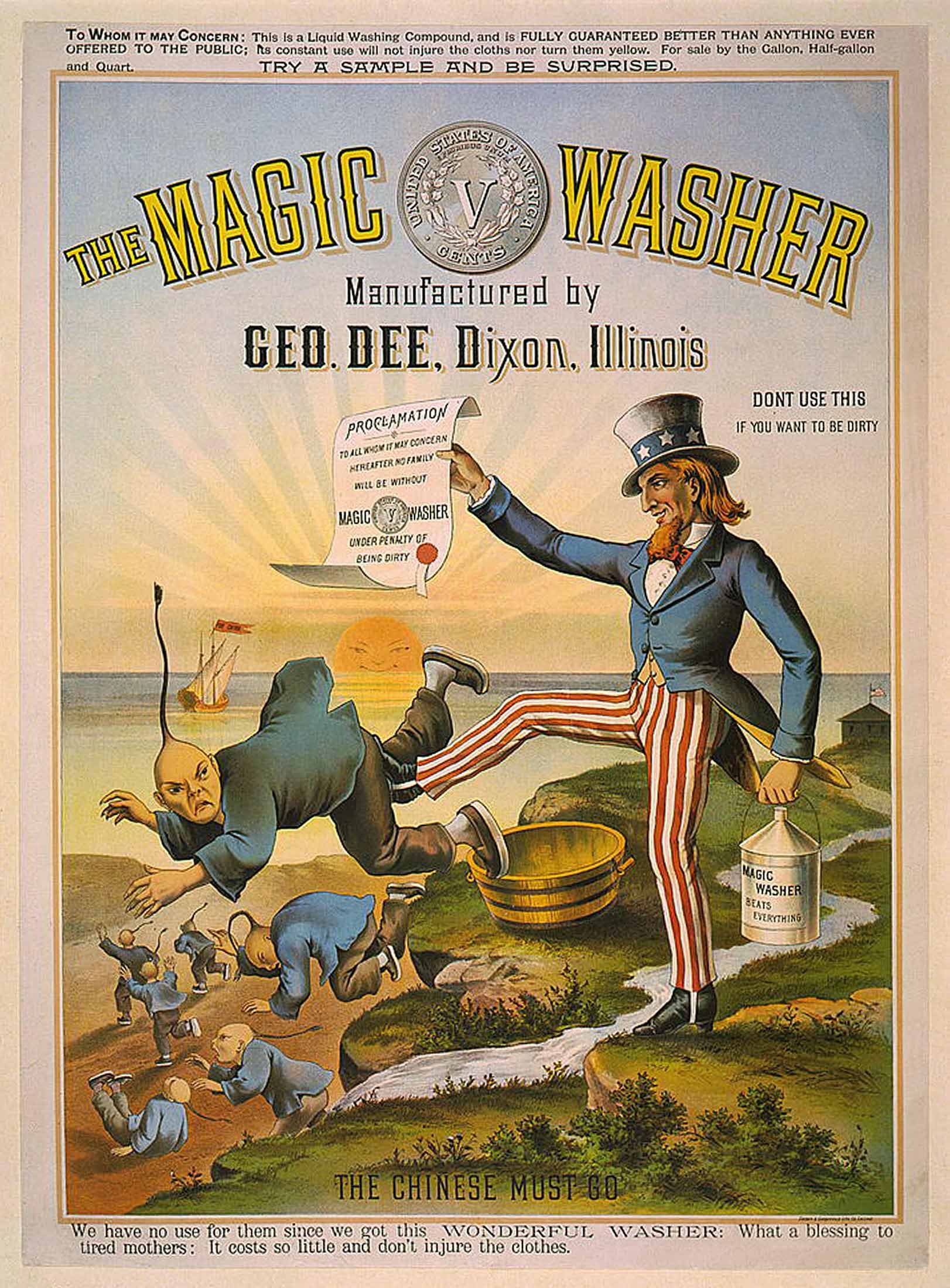

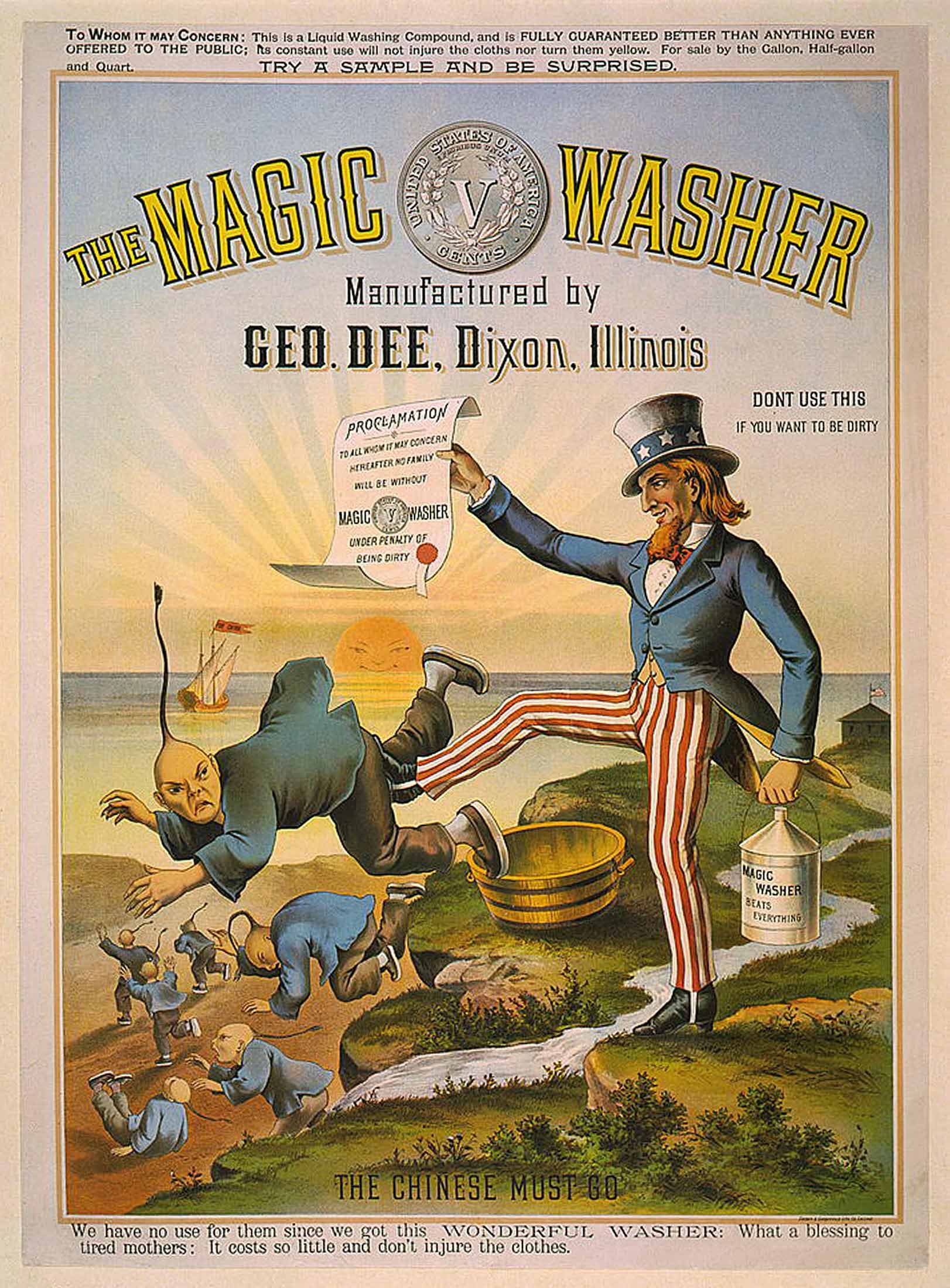

| Immigration has been one of this election's biggest issues, and Donald Trump has made mass deportation one of his signature promises. But, as reporters Enda Curran and Emma Sanchez write, experts are not enthusiastic about the economic impact of this policy. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. Donald Trump has repeatedly pledged to launch the largest deportation program in US history if reelected, to reverse a migratory tide he claims is "crushing" American jobs and wages. It's basically the same argument that has instigated all mass deportations in the US going back to the late 1800s. The notion that large-scale immigration hurts native-born workers by driving up competition for jobs and pushing down wages may seem intuitively right. Yet there's a pretty large body of academic research that challenges that thinking. It shows that instead of protecting American workers, deportation campaigns and restrictive immigration policies curb overall employment and relegate existing workers to lower-paying jobs. In a working paper published this month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of academics analyzed the economic fallout from a US law enacted in 1882 to expel what had been a critical workforce for Western states: Chinese laborers, many of whom toiled to build the transcontinental railroad. The authors found the Chinese Exclusion Act wiped out more than half of manufacturing establishments in the region, doing away with scores of jobs and reducing the number of White Americans coming West in search of work by 28%. A measure of lifetime income for White workers fell as a result. The law's effects on local economies persisted into the 1940s, the writers say.  Poster depicting Uncle Sam, with proclamation and can of Magic Washer, kicking Chinese out of the US. Chicago, 1886 Photographer: Pictures From History/Universal Images Group/Getty Images "We don't find any evidence that there were benefits among White workers or native-born workers who were the intended beneficiaries of the act," says Marco Tabellini, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School and one of the co-authors of the report. (The only exception were local miners, whose labor supply increased.) "What the Exclusion Act did was to slow down the extent to which White workers were able to find better paying jobs," he says. Another paper published in August surveyed the academic literature on large-scale deportations of unauthorized immigrants from the US and found a similar pattern repeated across almost a century. Here's one data point: The deportation of 454,000 individuals not authorized to be in the US from 2008 to 2015 reduced the hourly wages of US-born workers by 0.6%. It's been estimated that almost 8 million unauthorized immigrants form part of the US workforce–equal to about 5% of the total. A deportation program on the scale Trump has described would reduce the size of the nation's gross domestic product by 2.6% to 6.2%, according to a range of projections reviewed by the authors of the paper. "At 2023 levels those equate to losses to the economy of between $711 billion and $1.7 trillion," wrote Robert Lynch, professor emeritus of Economics at Washington college, who co-authored the paper with Michael Ettlinger, founding director of the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire. There's an inflation effect too. "If you deport a large number of workers, you're gonna probably create shortages in some industries," Lynch says. "And when there are shortages, demand's going to outstrip supply and prices are going rise. So in the short run, I would expect that there would be inflation." To be clear, the authors of these papers aren't advocating for unchecked immigration. Even Democrats, who've come under fire this election cycle for the way they've managed the border with Mexico, recognize that more stringent controls are needed to check unauthorized immigration. If she wins the presidency, Vice President Kamala Harris has promised to resurrect a border security bill that had support from many Republican legislators before Trump persuaded them to vote against it in February. Nevertheless, economic research does appear to refute Trump's argument that deportations will improve employment prospects for US workers. "What we are saying is that extreme restrictions are economically detrimental," Tabellini says. "At least they were at the time." Also: Mass deportation would not help with food prices either, writes Businessweek food columnist Deena Shanker in Trump's Immigration Policy Would Make Food Inflation Even Worse. Plus, the third installment of the series Courting Injustice, which reveals how US immigration courts deny many deserving asylum-seekers a fair hearing. There are examples, Michael Riley writes, of how to properly handle waves of immigrants, if only the US would heed them: How to End the Backlog of Asylum Cases? Take Them Out of the Courts |

No comments:

Post a Comment