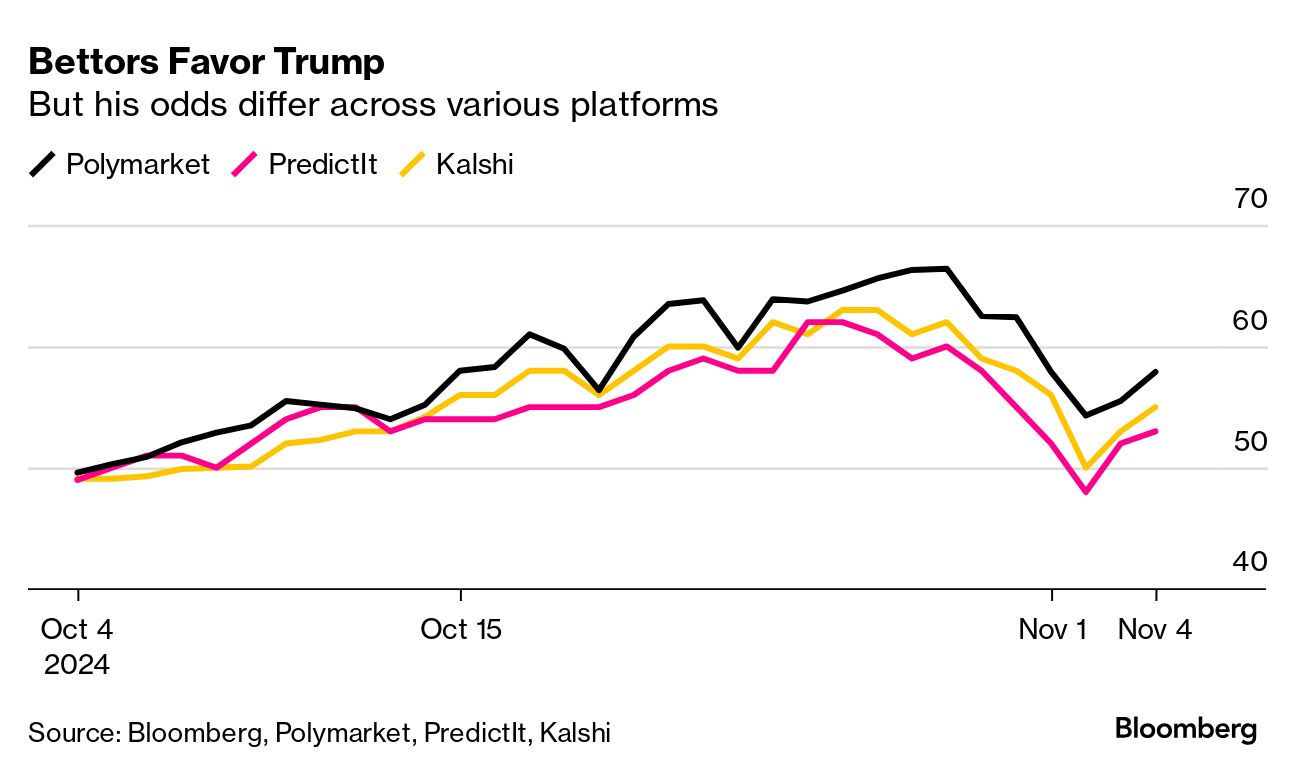

| Prediction markets have long been loved by economists and investors alike. Even niche platforms such as the Iowa Electronic Markets and betting pools inside companies like Ford Motor Co. all have been found to be superior than the alternatives in telling the future. Now though, the online emporiums have entered the big leagues with the 2024 presidential vote. Electoral betting is legal for the first time in modern-day US history and wagers worth hundreds of millions of dollars have piled up on betting sites. In theory, this means these markets are more liquid than ever and, as a result, that the conclusion they've been broadcasting as recently as last week — Donald Trump is the clear favorite over Kamala Harris — should be more accurate than a few notable misfires like the Brexit and US presidential votes in 2016. Yet even some supporters of prediction markets fret that too much faith is being put in their fortune-telling powers. "I'm a bit worried," said Rajiv Sethi, an economist at Columbia University who supported Kalshi in its successful effort to overturn a ban on the use of derivatives to wager on the election. As much as markets likes Polymarket have grown, Sethi said, they're still places where a handful of deep-pocketed investors can plunk down large bets and distort the odds — in Trump's favor, in this case. The prevailing wisdom on Wall Street is that prediction markets have an edge over polls because participants are economically motivated to incorporate every drip of new information faster. Between a single forecasting model and the wisdom of a crowd that has digested all that information, the latter might reasonably do better. There's been some evidence of that this year. Harris's odds jumped after Biden's disastrous debate when pollsters weren't even paying attention to her potential candidacy. In recent weeks, poll-based forecast models like FiveThirtyEight's have mostly been playing catch-up with Trump's higher betting odds. Yet over the last few days, Harris's chances have risen markedly in the betting markets, converging closer with the polling averages, a sign these odds had become skewed — or potentially were manipulated, critics say. Academic research has generally shown that even small markets betting on everything from geopolitical events to the box office can be fairly accurate. For elections, however, the question is how helpful they are relative to poll-based models. The scrutiny facing electoral betting even raises the question of whether its odds have somehow become less insightful in a more active market that's attracting big positions. In the stock market, a big one-way wager can still move prices, but with enough trading that effect should fade if it's not supported by fundamentals. Yet as anyone on Wall Street can attest to, that doesn't always happen immediately. "It would be naive for people to think that just because someone is putting money down that means they're going to have more information," said Andrew Gelman, a colleague of Sethi's on the Columbia faculty who worked on The Economist's election forecast model. "People make bad investments all the time." —Justina Lee |

No comments:

Post a Comment