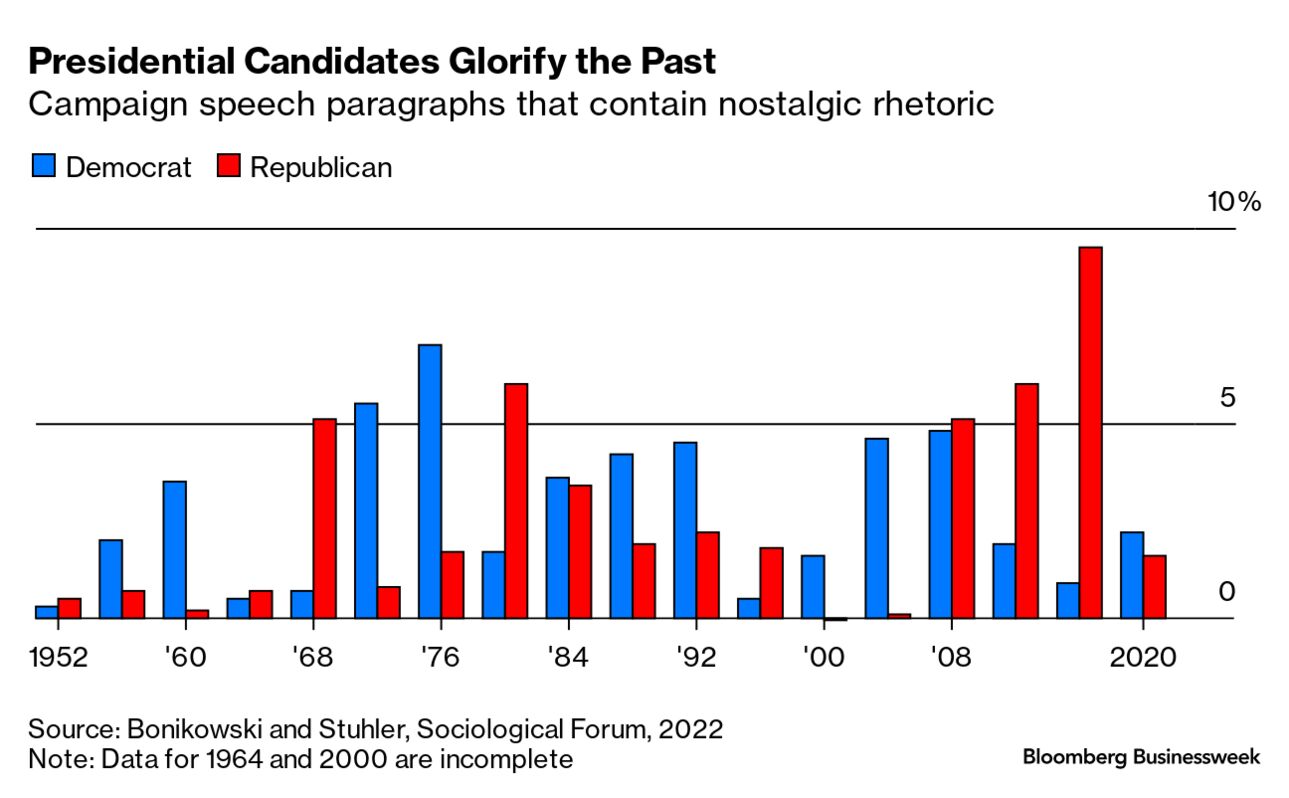

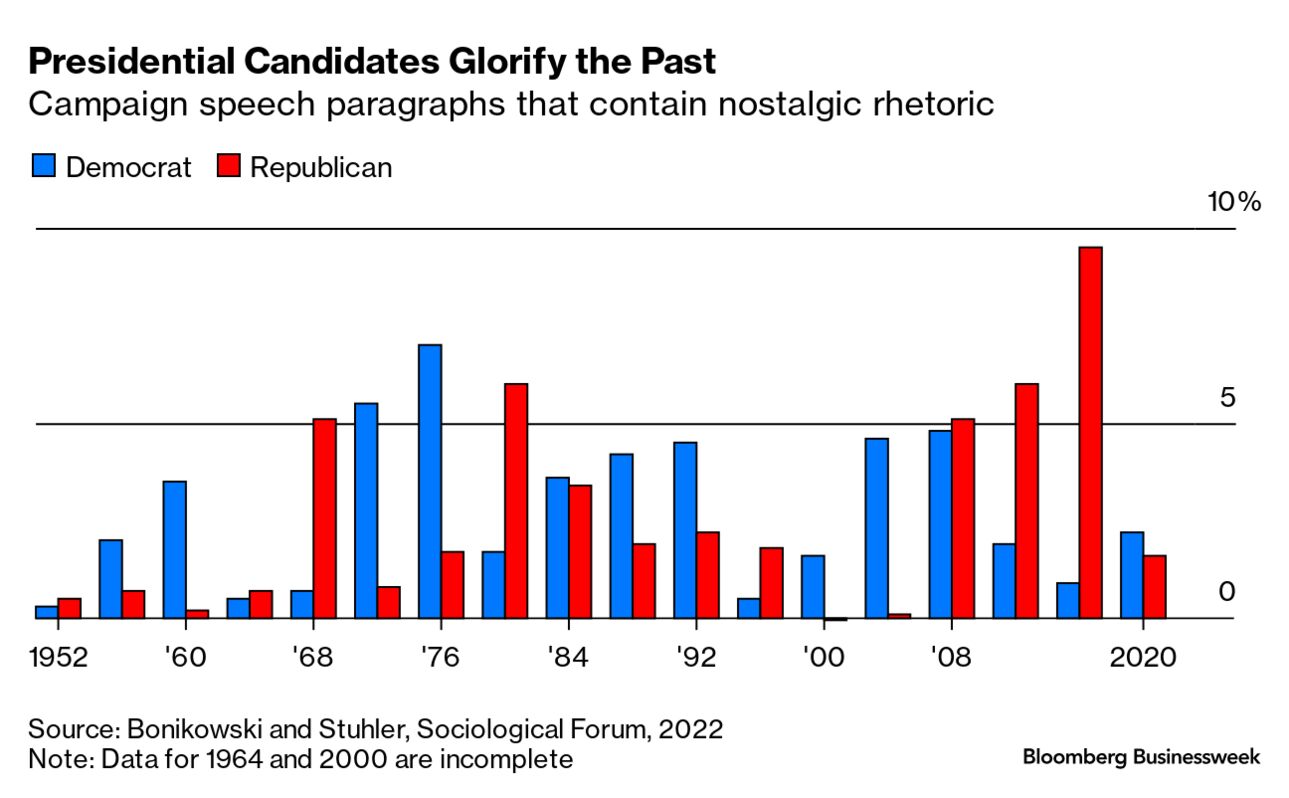

| Children are the future—and yet politics is often about the past. Bloomberg Businessweek deputy editor Mark Milian assesses how Donald Trump used nostalgia to get reelected. Plus: The Elon, Inc., podcast does a quick assessment of Musk's campaign role, and a look at polls' performance. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. This election was always about Donald Trump. Would Americans see him as a failed, one-term president—a convicted felon who brought dysfunction to the Oval Office, botched the country's response to Covid-19 and stoked an insurrection—or as a change agent and standard bearer of American values who can repair a damaged economy and secure the borders? Voters chose the latter. It's clear in hindsight that Kamala Harris, the sitting vice president, was seen as the incumbent and carried the blame for the punishing inflation and rising immigration seen on Joe Biden's watch. That wasn't so obvious before Election Day. The Democrats ran against Trump for the past three elections. His presidency and defeat in 2020 really weren't that long ago. If the US didn't want him back then, how much could possibly have changed in four years? Trump is, in some ways, as much of an incumbent as he is a challenger. But he chose to run a challenger's campaign, and it worked. One of the most powerful devices in politics—and in business—is nostalgia. But nostalgia is a challenger's tool. An incumbent can't say, "Don't you wish things were the way they used to be?" That isn't a winning strategy for the person already in charge. Bart Bonikowski, an associate professor of sociology and politics at New York University, has studied the prevalence of nostalgia in US presidential races dating back to 1952. The breadth of his research, published in 2022, was enabled in part by machine learning technology based on a precursor to ChatGPT, which Bonikowski used to analyze campaign speeches. He was interested in how often candidates evoked fond memories of the past. "We knew that nostalgia was an important motif," he says. "What we didn't know is how common this was over a longer historical period."  In Richard Nixon's 1960 run against John Kennedy, he campaigned on policymaking and goals for the future. He lost. Nixon reemerged eight years later with a nostalgia-rich appeal, pledging to "restore respect for America around this world." Ronald Reagan built on the technique in 1980, invoking the glories of the past in 6% of the paragraphs in his speeches. He called for "a rebirth of the American tradition of leadership" and made a "pledge to restore to the federal government the capacity to do the people's work without dominating their lives."  Nixon before a crowd of supporters on Sept. 17, 1968, during his second presidential campaign. Photographer: Bettmann/Corbis/Getty Images Even Barack Obama, whose 2008 run is remembered for its forward-looking slogan, "Hope," understood the power of nostalgia. He accused the George W. Bush administration of squandering the US's legacy of excellence abroad and promised to "restore our moral standing." Trump's first ascension to the White House was, of course, driven by a nostalgic message: "Make America Great Again." "It is nostalgic by definition," Bonikowski says. Trump used nostalgia at a higher frequency, in 9.5% of all paragraphs, than any other presidential candidate in a lifetime. Nostalgia is a powerful weapon of persuasion. It allows us to reminisce about a time in our lives we long for, shaded in sepia tones and freed of any gloomy memories, and it connects us through shared experiences; it's a social emotion. Just as nostalgia rules Hollywood, helps mint cryptocurrencies and keeps the video game business humming, it's prevalent in elections worldwide. Challengers in Asia, Europe and Latin America have used it to great effect recently, Bonikowski says. It's not a good time to be an incumbent. Bonikowski hasn't yet studied the 2024 US race in the same level of detail as he did for his peer-reviewed paper. What he's observed from reading many of the speeches himself is that Harris studiously avoided nostalgia, right down to her campaign message: "'We Are Not Going Back' is the epitome of an anti-nostalgia slogan. I'm sure it was designed exactly as a counterpoint to 'Make America Great Again,'" Bonikowski says. Meanwhile, Trump used essentially the same, nostalgia-heavy tactics as he did in 2016. "He has been using this strategy, banking on the hope that he's not seen as the incumbent," Bonikowski says. In the US, the prospect of a former president running again after losing is generally ill-advised. The only other time it worked was more than 100 years ago, when Grover Cleveland won an unusual election largely devoid of campaigning. Nobody remembers that, obviously, but it turns out that even four years ago is a bit fuzzy in the popular consciousness. With that, Trump offers a new model for future presidents trying a third time: Look to the past. |

No comments:

Post a Comment