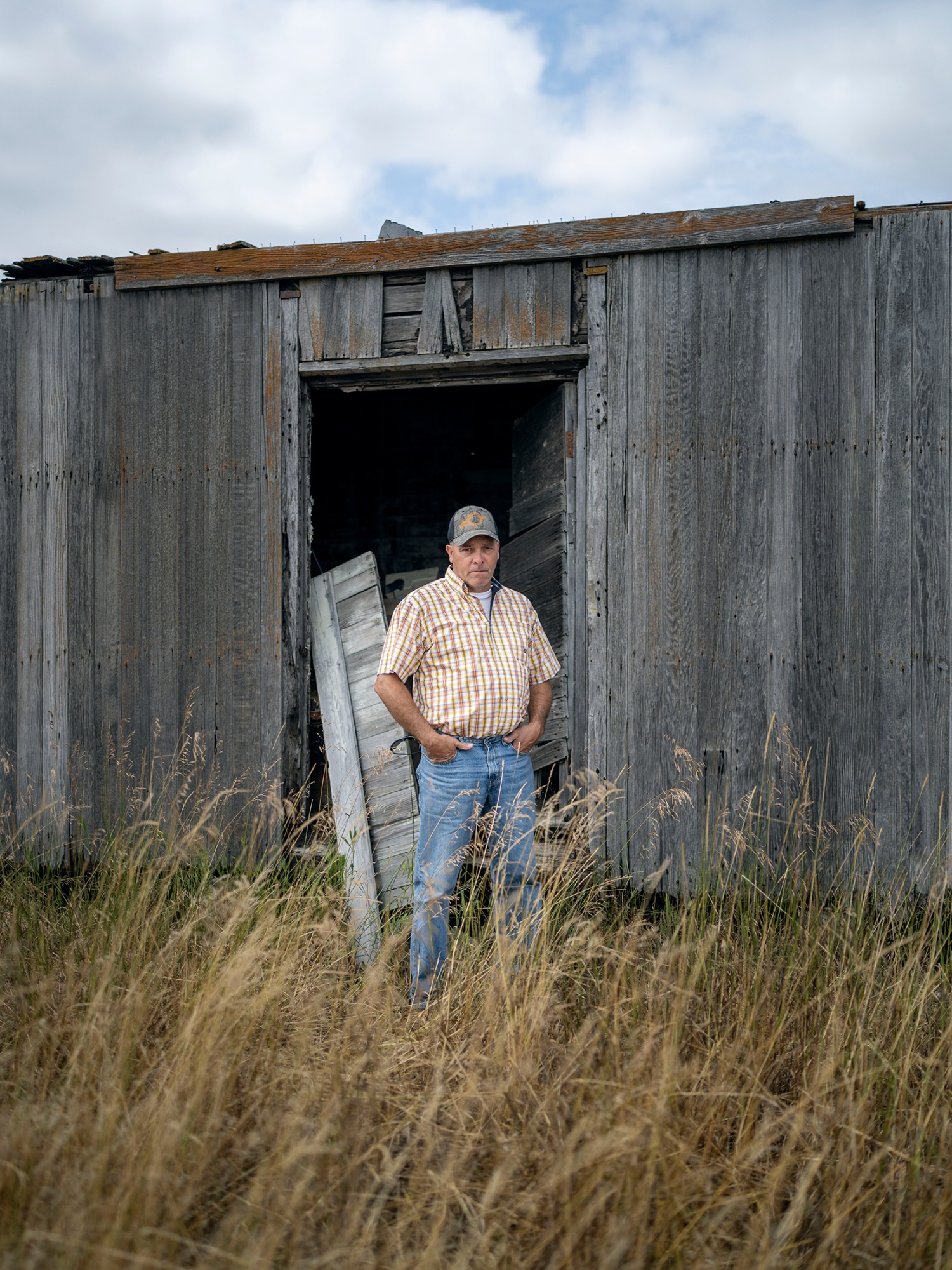

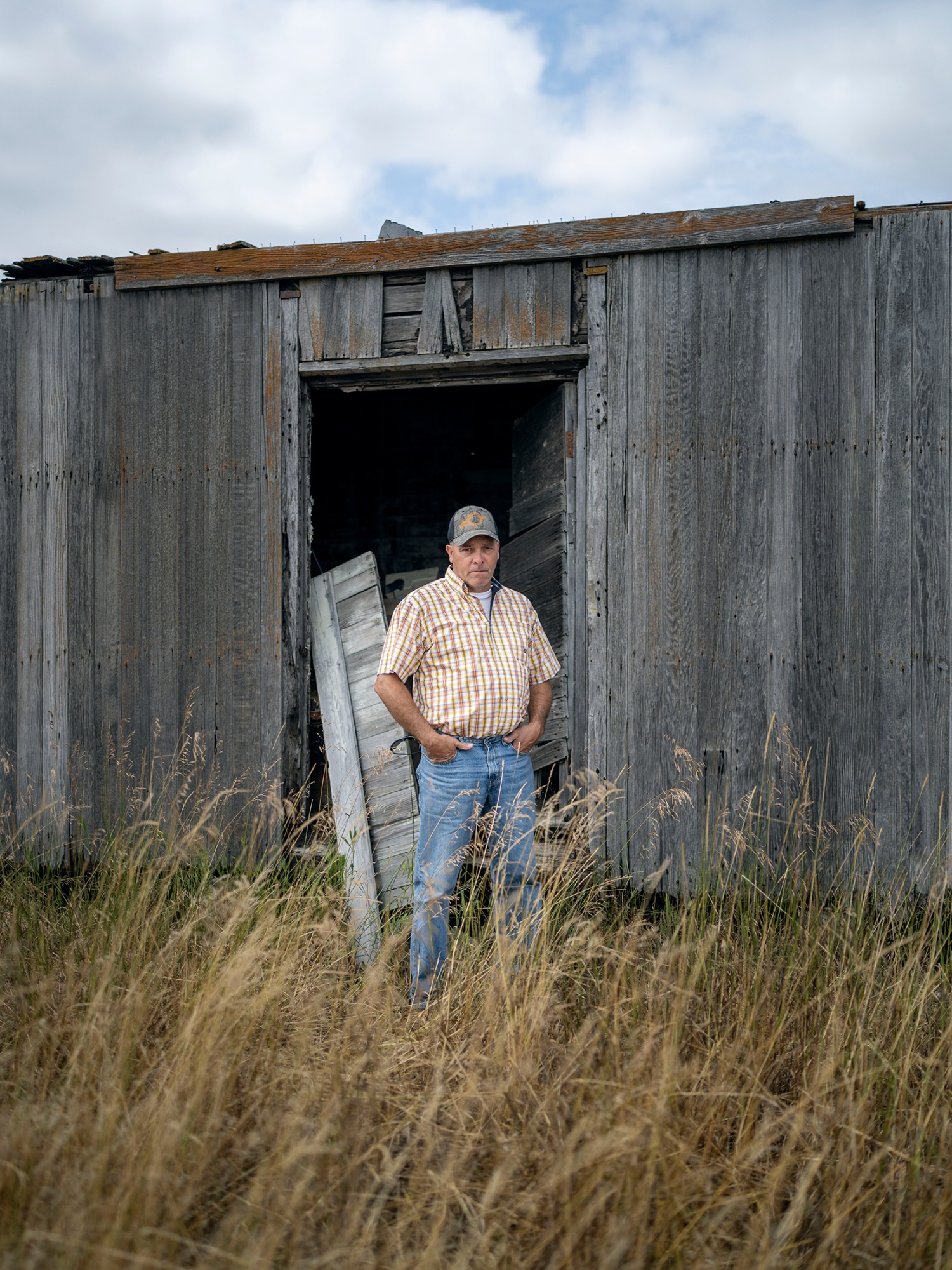

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today it's Adam Willis' tale about a $9 billion plan to entomb CO2 emissions in the Great Plains. The idea isn't without controversy, but it could allow the region to keep pumping oil and burning coal. Since this article published, there's been news, as regulators approved a span of the pipeline on Friday. You can find Willis' whole story online here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. Jason Erickson is a landman on the ranches and farms of western North Dakota. Traditionally, the title refers to someone who brokers the deals wildcatters need to drill for oil on private land. But Erickson belongs to a new breed in that old line. What he does is different, an inverse. He seals land deals so that atmosphere-warming carbon dioxide—hundreds of millions of tons of it—can be pumped deep underneath. It's been four generations since Erickson's family first arrived in North Dakota, and their piece of prairie is still littered with remnants of his homesteading ancestors: a windblown shack built by his great-grandfather, the boxcar where his grandparents lived as newlyweds. A more recent addition, a 6,400-foot-deep shaft on his property called Archie, after his grandfather, burrows into the same quarter-section where his grandparents parked a wagon to stake their claim almost a century ago. If all goes according to plan, the well will be used to monitor a vast underground reservoir of CO2 that could rest there forever. This carbon-sequestration project, which Erickson first began peddling to his neighbors more than three years ago, would be the largest of its kind in the US, an $8.9 billion venture by Iowa-based Summit Carbon Solutions LLC. Using carbon capture—until recently a fringe technology, and one that's still largely shunned in environmentalist circles—Summit aims to pool emissions from 57 ethanol plants across the region and lock them more than a mile into the Earth, capitalizing on a federal tax credit that pays companies to bury CO2.  Erickson in front of the railroad boxcar his grandparents lived in. Photographer: Lewis Ableidinger for Bloomberg Businessweek The more controversial part of Summit's plan is a 2,500-mile web of pipeline known as the Midwest Carbon Express. Originating at ethanol plants in Iowa, the pipeline would wend its way north and west, gathering emissions at biorefineries in Nebraska and Minnesota before stretching through South Dakota and eventually reaching its terminus west of the Missouri River, beneath the prairie surrounding Erickson's land. The pipeline plan has embittered farmers, environmentalists and land-rights defenders across the region, prompting a populist alliance that threatens to block the whole enterprise. At the pipeline's endpoint, though, on the ranches beneath which Summit hopes to bury its CO2, the plan is broadly accepted. In fact, some consider it a way to almost stop time. For North Dakota, whose economy depends heavily on oil and coal, the transition to cleaner fuels poses an existential threat. If plans such as Summit's work, the region's carbon-capture advocates attest, life here might go on basically as it has for decades. "I'm not out here saying we're saving the planet," Erickson told me. "I want to sustain the fossil fuel industry, and, to me, this is a way we're going to do it." Erickson is stocky, broad-shouldered and a smooth talker. He left the ranch where he grew up to work in the oil fields for more than two decades, through the height of North Dakota's fracking boom, but returned home to his cows a few years ago. Now 54, he has a soft, neighborly face and a Northern Plains accent so heavy it sounds almost Irish. Both have been assets to him in the job for Summit. Leasing is often conducted over beers or country cooking. The work can still be taxing. In the project's early days, Erickson and a small team of other Summit recruits—mostly neighbors and former schoolmates of his—worked 20 hours at a stretch to blanket their area in carbon storage leases, agreements that now cover 145,000 acres. Erickson often logged hundreds of miles a day on the grid of section-line roads surrounding his home. He broached Summit's idea with neighbors in their driveways, at the foot of tractors and at kitchen tables. He preferred to do it face-to-face, his wife, Angie, told me, the "cowboy way." One neighbor, a friend Erickson recruited into the original Summit team, recounted that Erickson would stop at her place several times a day to drop off contracts before hitting the road again, off to another kitchen table. His staid Dakota charm never faltered. But if he had to accept one more caramel roll, he told her after lumbering through her door at the end of a long day, he was going to explode. Keep reading: North Dakota Wants Your Carbon, But Not Your Climate Science |

No comments:

Post a Comment