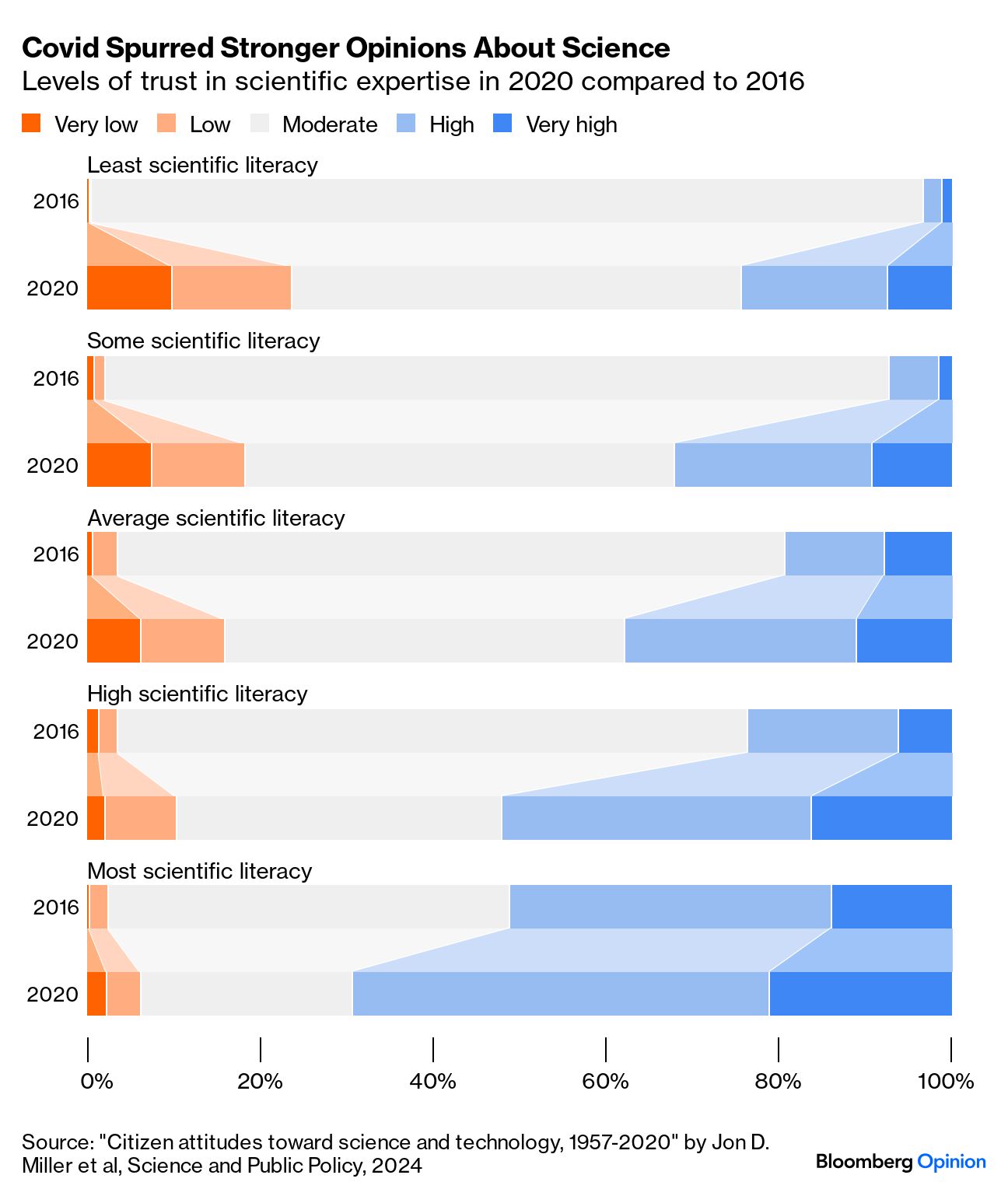

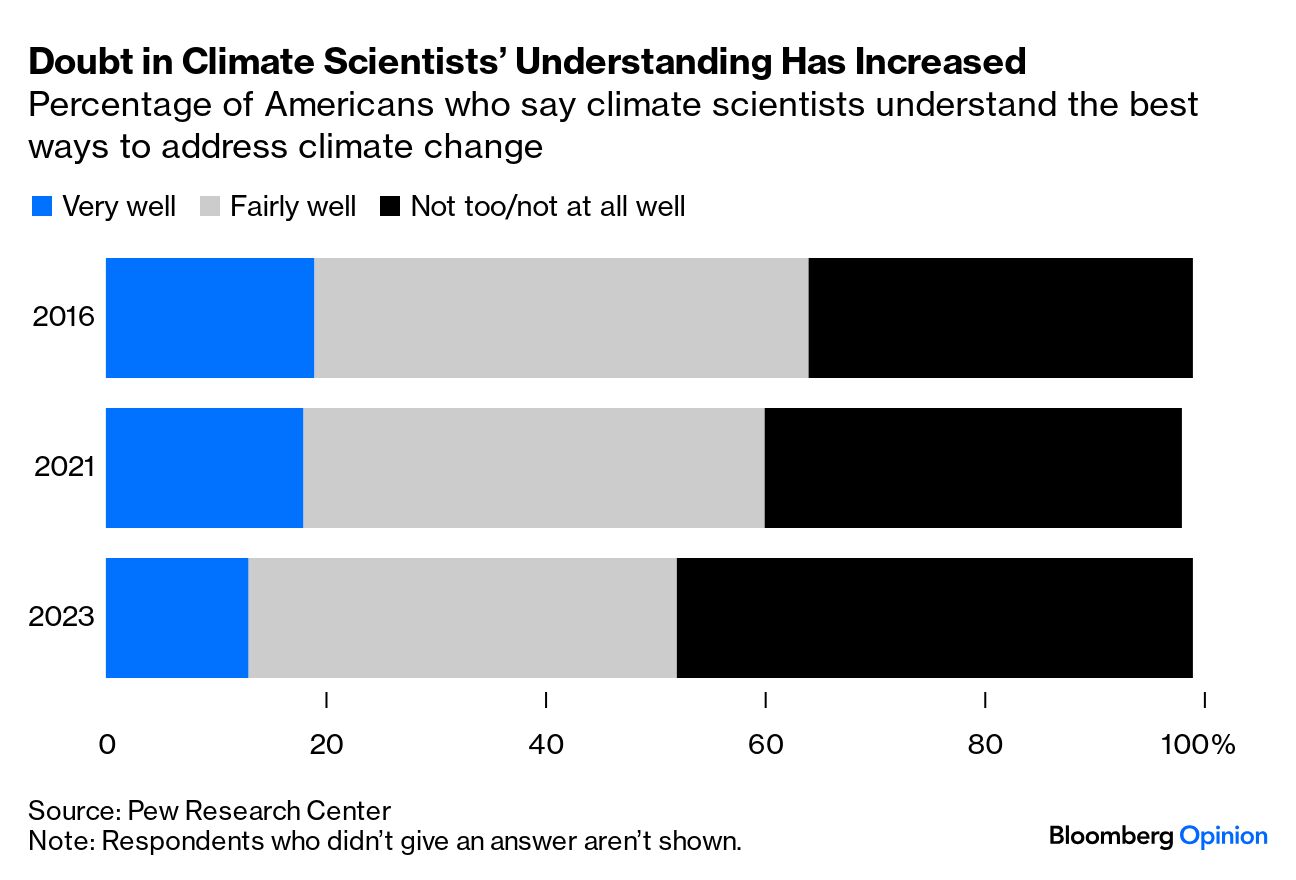

| I'm Lara Williams and this is Bloomberg Opinion Today, an uncertain science of Bloomberg Opinion's opinions. On Sundays, we look at the major themes of the week past and how they will define the week ahead. Sign up for the daily newsletter here. In these strange, divided times, almost anything can fall prey to conspiracy theories. Even something as apolitical as the weather. As Florida deals with the aftermath of Hurricane Milton, let's cast our minds back to the beginning of this week when a video of NBC meteorologist John Morales went viral. In the clip, he's giving an update on Milton, which had rapidly intensified to a Category 5 storm, and almost chokes up. Weatherfolk like Morales play a pretty crucial role during an extreme event like this, informing people about the steps they need to take in order to stay safe and, increasingly, educating TV viewers about the impacts of climate change. In today's world, the two responsibilities often go hand-in-hand. A rapid attribution study found that climate change increased rainfall from Milton by 20-30% and made wind speeds about 10% stronger. People, you would imagine, tend to want to know about threats to their homes and families and so meteorologists, you would expect, should be pretty popular people. Apparently, not so much anymore. Morales wrote in a column for Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that, after Helene, he was accused of being a "climate militant" who was "embellishing extreme weather threats to drive an agenda." Other meteorologists have been sent death threats and, alongside delivering life-saving information to the general public, have been forced to spend time debunking misinformation and fighting conspiracy theories. You may reasonably wonder how a hurricane — formed by a complicated recipe of just the right amounts of warm water, low pressure and wind shear — could possibly form part of a conspiracy. Among the wild narratives is the idea that hurricanes like Helene and Milton are man-made "weather weapons" created to "kill Trump supporters and interfere with the election." Even elected officials are getting involved! At the start of October, Republican congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene wrote on X: "Yes they can control the weather." (Who "they" are is unclear.) On Monday, she wrote that "climate change is the new Covid."  How hurricane conspiracy theorists make me feel. Source: Meming Wiki Needless to say, cloud-seeding wasn't used to create Milton, nor did it cause the floods in Dubai earlier this year. But perhaps Marjorie Taylor Greene is right – just not in the way she thinks she is. In this week's installment of Bloomberg Opinion's Republic of Distrust series, F.D. Flam explores how Americans' faith in science was altered by the pandemic. You see, prior to 2020, trust in science overall was pretty steady. But there was a shift – the middle ground was hollowed out, with people growing increasingly skeptical or increasingly trusting of scientific expertise. Covid-19 was a driving force behind this schism. We all had a laser-focus on what researchers were discovering; lingo such as "T cells" and "R numbers" entered into everyday conversation. The issue is that we also learnt just how uncertain science can be. As Flam explains, those working in public health had an unenviable job: "Explain their constantly evolving knowledge of the virus and find ways to keep individuals and communities safe. In doing so, they too often chose a false sense of certainty over the transparency that's at the core of the scientific method." Advice evolved, but it felt contradictory: First, the virus likely wasn't airborne, then it probably was. This, coupled with the edict for policy to "follow the science" allowed research to become politicized — and for conspiracy theories to flourish. We're now seeing this polarization feed into the climate — and hurricane — space. A majority of US adults may trust what scientists say about the environment, but that trust looks shaky. In 2023, the Pew Research Center found that US adults rated climate scientists' understanding of the causes and solutions lower than in 2021. That's pretty worrying. In order to roll out clean energy, grid upgrades and potentially new forms of climate technology, trust is essential. It's particularly important in an emerging area of the climate space called carbon dioxide removal (CDR). In the process of burning fossil fuels, we've added a bunch of extra CO2 to the atmosphere. CDR works on the theory that we can pull that back out of the atmosphere — where it's trapping extra heat — and store it permanently somewhere down here. Decarbonization is absolutely essential, but once we've got close to zero emissions, carbon removal could offset the last dregs and potentially help cool us off again (In an example of the uncertainty integral within science, researchers are divided on whether that's possible). The public largely trust methods that seem close to nature: tree-planting, for example. But novel techniques, such as direct air capture (giant sky vacuums) and ocean alkalinity enhancement (accelerating the ocean's natural carbon cycle), can seem pretty scary. It's understandable. After all, adding chemicals to the ocean goes against the narrative that we shouldn't dump stuff in nature. Research and trials are important if we are going to use these methods, and the public must have faith in them, too. I chatted with a bunch of different startup workers who told me that the key is community engagement, local benefits and plenty of transparent, objective information. Still, for every startup doing their best to develop carbon removal in an ethical, safe way — there's a carbon project that lies. Matt Levine writes about the first carbon-credit fraud case, which is unlikely to be the last. So, the story goes, that carbon-credit project developer CQC Impact Investors did really want to create a good carbon offset program. The way they set out to do it was by installing cookstoves in rural Africa and southeast Asia. These cookstoves were more efficient than cooking methods already being used (a typical fuel in these areas is charcoal, which not only results in carbon emissions but involves chopping down trees). But uh-oh: What if you realize they're not as efficient at reducing carbon emissions as you thought? Well, you could come clean or, as Levine writes: "Just like anyone else who took investor money to do a business that didn't quite work, you might be tempted to fudge the data." Which is why two former executives have been charged with A) manipulating data to fraudulently obtain carbon credits and B) using that data to deceive a backer into investing more than $100 million in the firm. Levine makes the point that carbon credits are actually fairly easy to run a fraud with — no buyer wants you to deliver a ton of carbon dioxide to their desk. So how did this fiendish skulduggery get uncovered? "While CQC's CEO was allegedly cool with selling fake credits," explains Levine,"its other employees and its board of directors were not." So we should end with a thank you to the meteorologists, scientists and honest brokers of the world for trying to keep climate action trustworthy. I can only hope they succeed. Notes: Please send feedback to Lara Williams at lwilliams218@bloomberg.net (keep your dodgy carbon credits). |

No comments:

Post a Comment