- Two years on, Liz Truss has officially given her name to a Moment, and sterling has rallied 29%.

- The damage to Britain's economy wasn't so severe — but her fate scared the living daylights out of politicians the world over.

- If there's another Truss Moment, there's a risk it could come in France.

- China's rates position will perhaps be more important than the Fed's.

- AND: Some more starry songs.

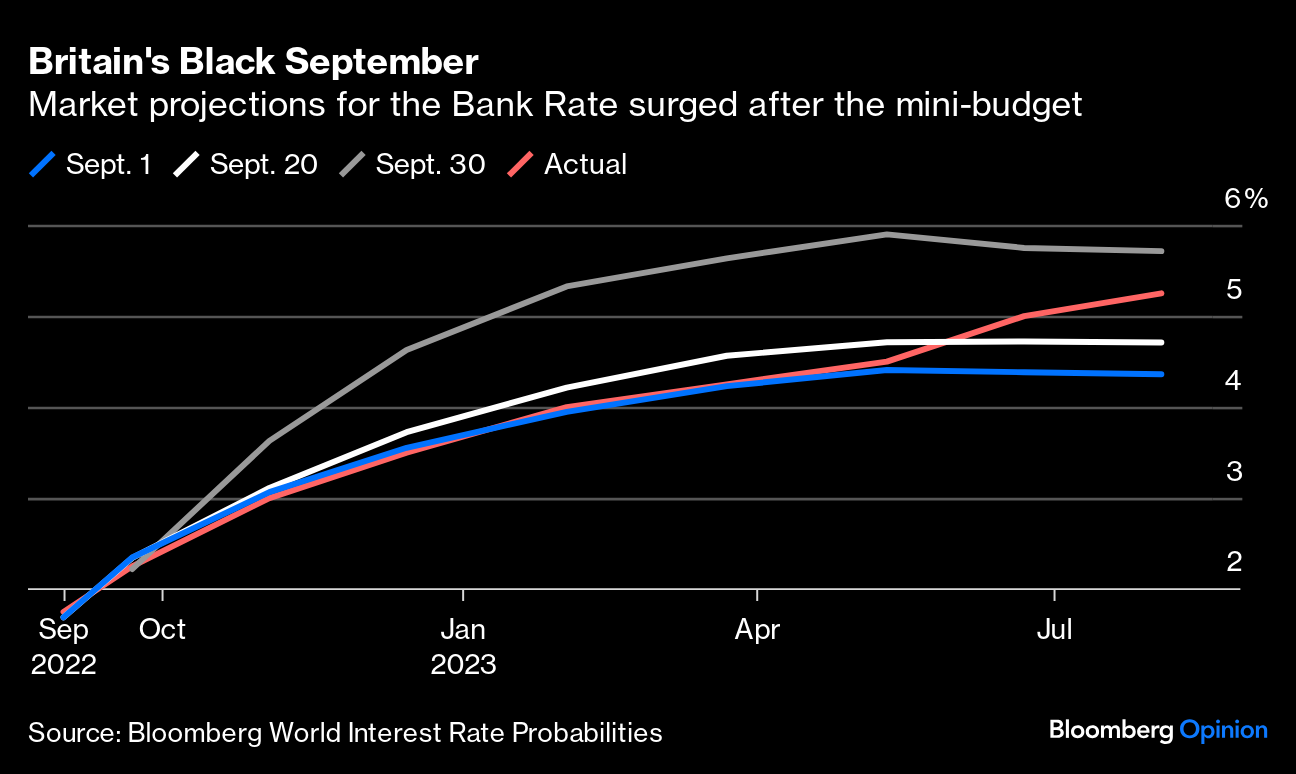

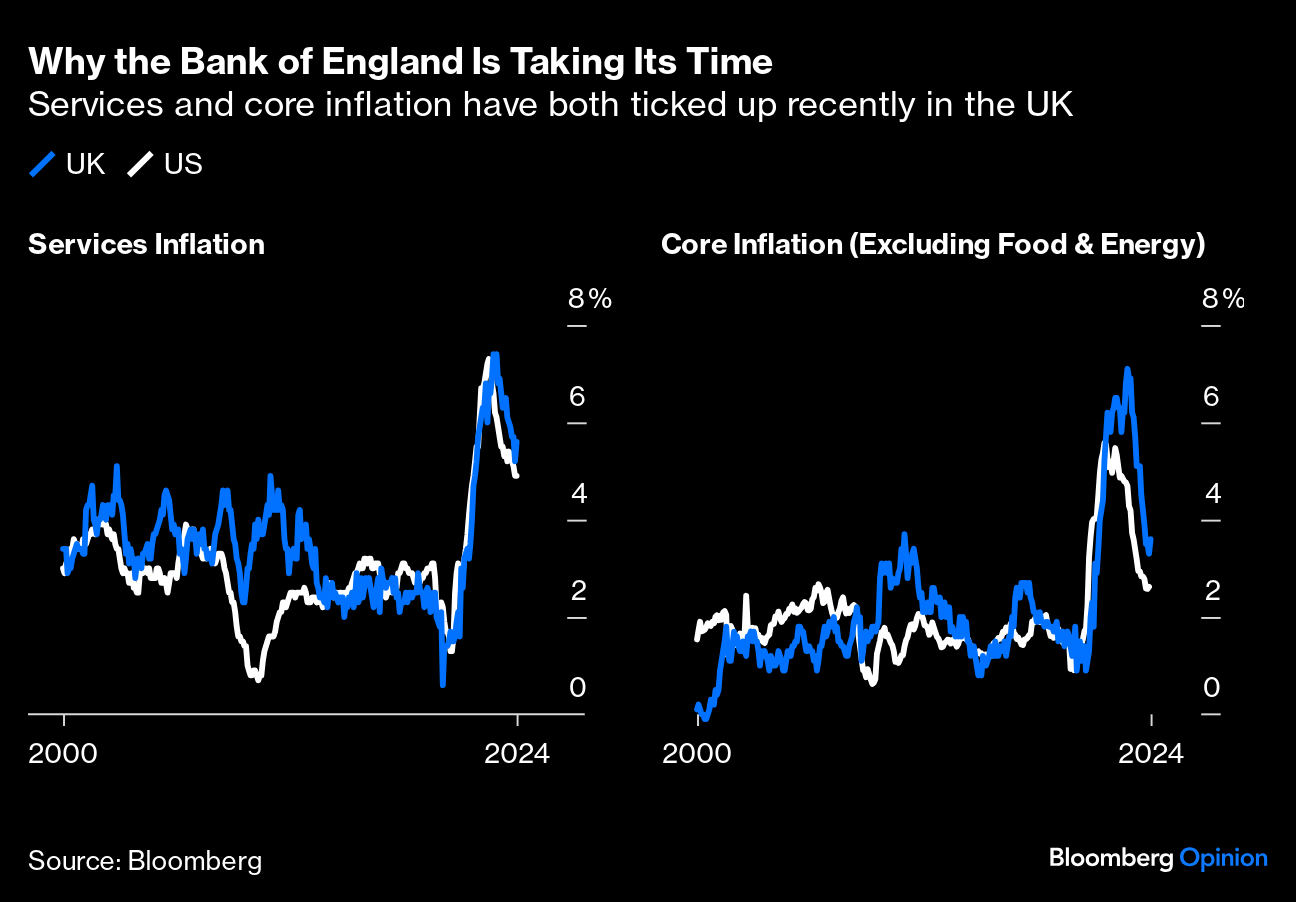

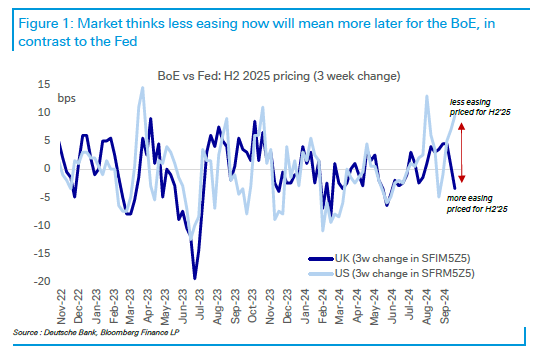

It's exactly two years since the new UK government under Liz Truss announced sweeping unfunded tax cuts in a "mini-budget." Truss was out of power within a month, but she did join the ranks of Paul Volcker, Hyman Minsky, Wile E. Coyote and Lehman Brothers in the financial literature by having a Moment named for her. The legacy of the Truss Moment, in which the gilts market revolted and the pound dropped to an all-time low against the dollar, is growing more complicated. The Bank of England's decision not to change its policy rate last week, the day after the Federal Reserve had slashed fed funds by 50 basis points, helped the pound to its highest level since early in 2022. From the low it plumbed in the immediate wake of the mini-budget, it has now rallied by 29%:  For the pound, then, the Truss implosion hasn't done lasting damage; once the economy was back under adult supervision, it traded like a developed market currency once more. The story of gilts is somewhat similar. Gilt yields rose in the summer of 2022 as it became clear that Truss would win the premiership and was committed to a loose fiscal policy. They went through the roof after the budget, but their spreads over Treasuries rapidly fell as soon as her new finance minister hustled to step back from most of her proposals. Since then, however, gilt yields' differentials compared to Treasuries have continued a gradual rise. The Truss shock looks like an aberration in an ongoing trend, not a total game changer:  For another view, look at how overnight index swaps were pricing the BOE's future monetary policy during the fateful month of September 2022. Already braced for a sharp rise as the month dawned, this edged up by the eve of the mini-budget. It jolted far higher as investors calculated that the Bank would have no choice but to hike aggressively to protect the currency and counteract the fiscal splurge: But it's interesting that the Moment was momentary. For six months after Truss resigned, the Bank followed exactly the rate path that the market had discounted before she even took office. But in the summer of 2023, it took the hiking campaign further than had been anticipated, largely because inflation was proving sticky. Truss had prompted an epic implosion, but the damage had swiftly been remedied. It's not at all clear that she should be held responsible — as she largely is in the UK — for the high rates that the BOE eventually imposed. That has more to do with price rises. The one-word explanation for how the BOE and the Fed diverged last week is "inflation." Core inflation and services inflation remain above target for both. They're higher in Britain, and ticked up last month. That slowed down the BOE (and the Fed might do the same if it encounters a similar inflationary blip): For now, investors seem confident that the two big central banks have merely been briefly diverted from paths leading to the same place. This is from the fixed-income team at Deutsche Bank AG: Over the past three weeks, the market has priced in more cuts for the second half of next year for the Bank of England, while at the same time reducing the amount that it expects the Fed to ease between the middle and end of next year. It's rare to see expectations move in completely opposite directions, but the market thinks cutting more now will leave the Fed with less to do in a year's time, and vice versa for the BOE.

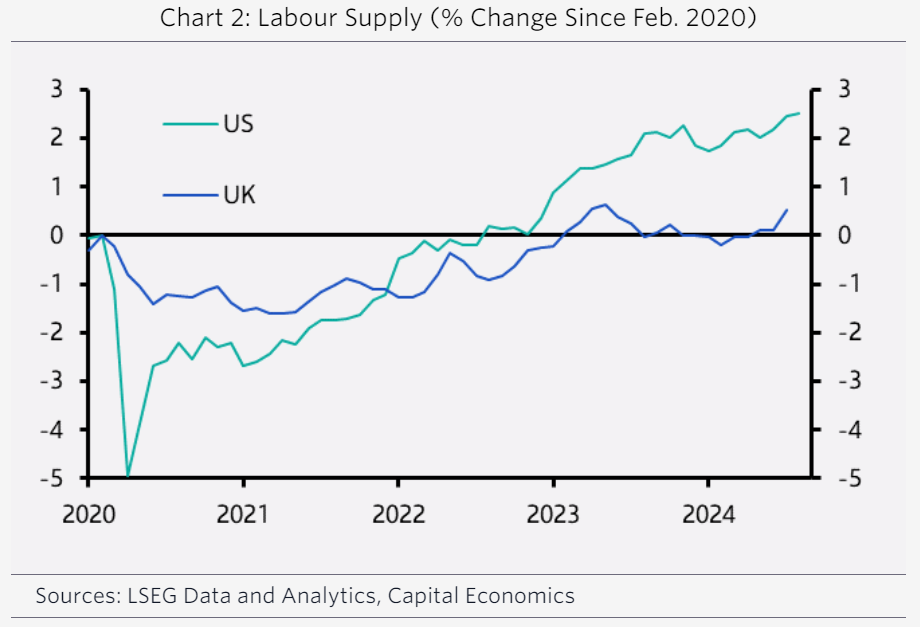

The effect is clear from futures pricing, and suggests that the excitement over whether the Fed would start with a jumbo cut was badly overdone: Beyond that, the BOE has to deal a problem that predates Truss — the shock to the supply of labor in the UK administered by Brexit. As Capital Economics illustrates, labor supply in the US has only just recovered to its pre-pandemic level: That gives the BOE solid reasons for maintaining tighter money than the Fed. As summed up by Ashley Webb of Capital Economics: So while the Fed is more concerned about the US labour market cooling rapidly, the stickiness of services inflation in the UK suggests the Bank is right to not yet shift from worrying less about inflation and worrying more about weak activity.

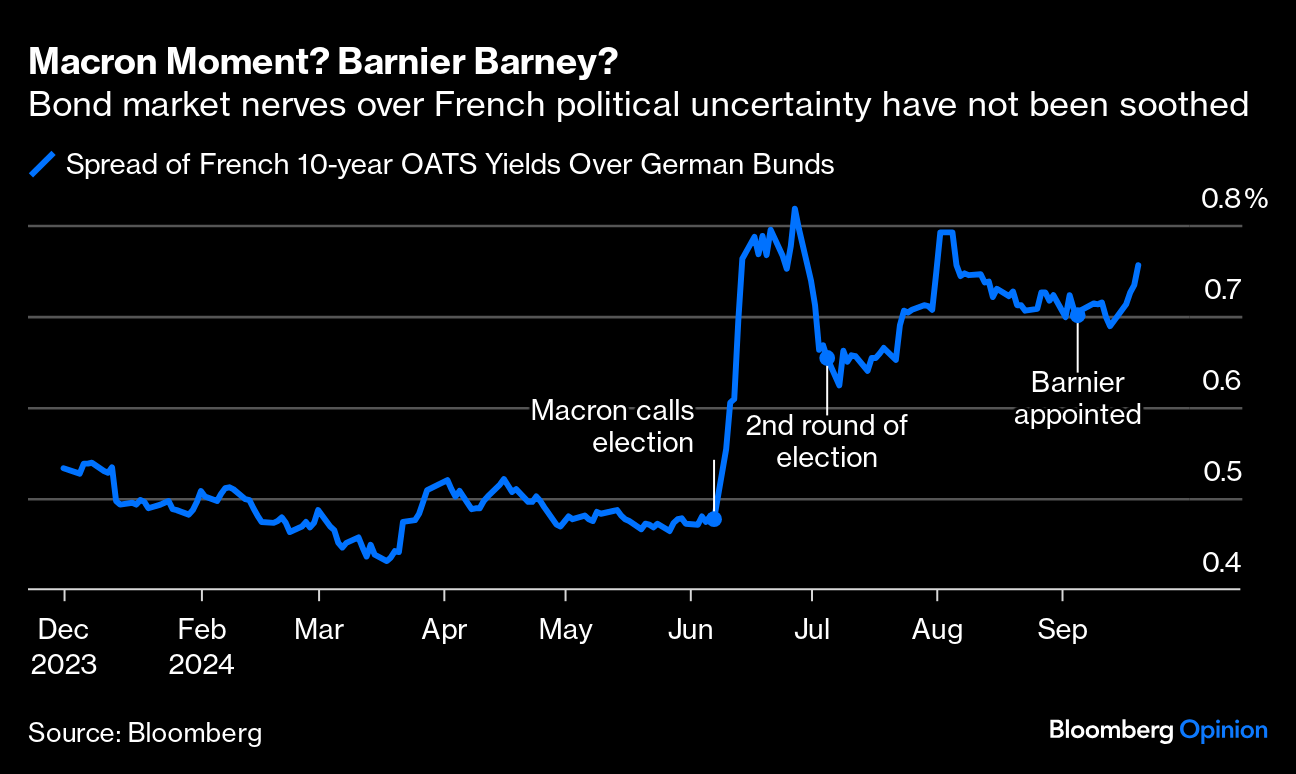

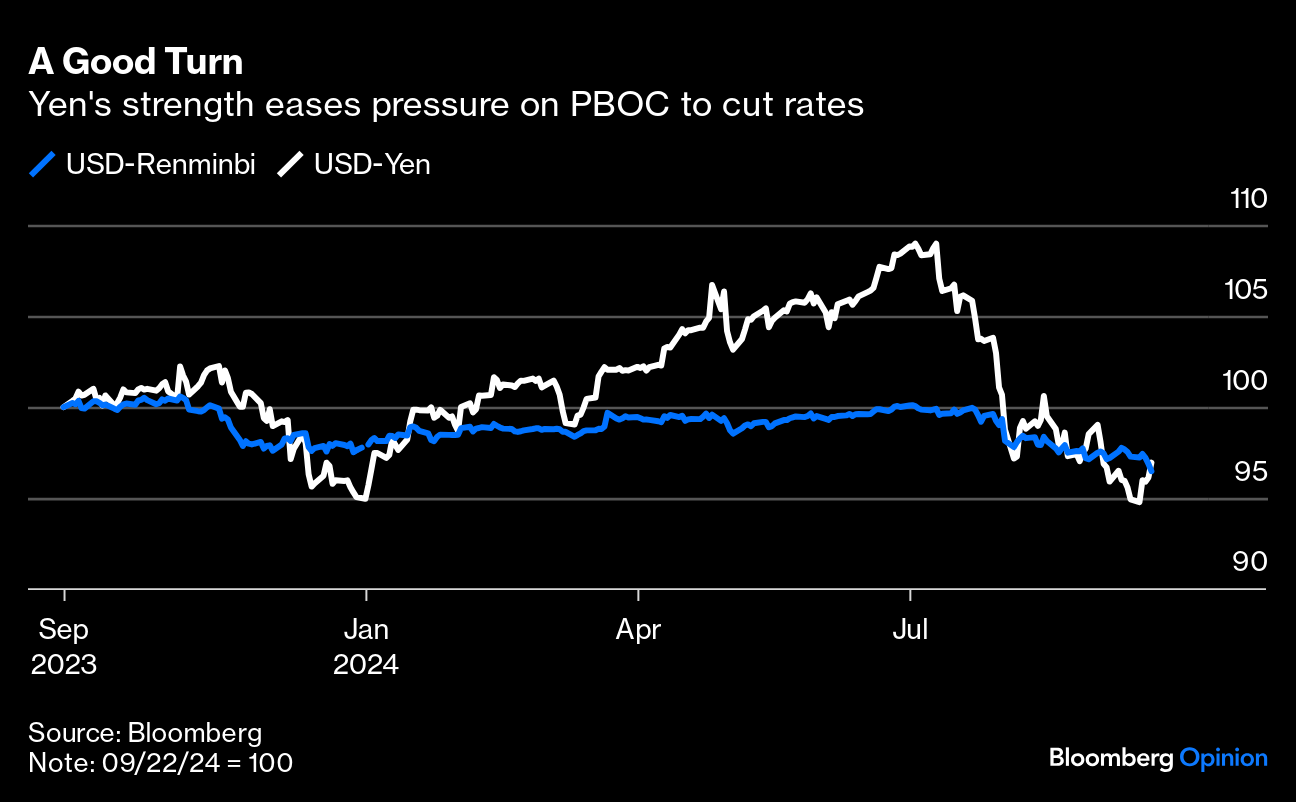

What of the lasting legacy of the Truss Moment? Sudden moves toward much more generous fiscal policy can provoke the bond market to revolt. As many countries, including the US, have huge deficits after the pandemic, that's a concern. Secondly, it revealed that even a historic and stable power like the UK is vulnerable to a loss of confidence if investors think its government is truly incompetent. In 2022, the currency collapsed as yields rose; normally, higher yields would strengthen the pound as they are doing now. That dynamic, reminiscent of emerging market crises, showed that trust in a country like the UK is fragile and dissolves if the competence of politicians comes into question. Thus the Truss Moment has disciplined the world's economy. Politicians are terrified to share her fate, so big unfunded tax cuts are out. It's possible they've over-compensated; Britain's new Labour government, elected in July, has already slipped into trouble as it prepares for what could be an austerity budget. That's bad politics, and there's a risk that it will weaken the economy unduly. But the risk of another Truss Moment looks greatest in France, where deficits have long been mounting. British newspapers gleefully warned President Emmanuel Macron that he faced "un moment Liz Truss" when he called legislative elections for July. The political mess is unresolved. The National Assembly is divided almost exactly three ways, and the new prime minister, Michel Barnier, an un-Trusslike figure, has been deluged by criticism since announcing his government over the weekend. A budget is due soon. As in the UK two years ago, bonds are sending warnings: Barnier himself inspires more confidence than Truss, but it's reasonable to fear that France's elections have left it with such a fractious group of politicians that they're incapable of making necessary decisions. That's the worry that Barnier must now somehow allay. Increasingly, China is in a world of its own. Its economy badly needs to stimulate domestic demand, so the Fed's jumbo cut last week created an opportunity for the People's Bank of China to ease. Curiously, it has barely done anything as yet, restricting itself to a 10-basis-point cut in its 14-day lending rate, which was little more than catching up to changes announced in July. Why so relaxed? The likely explanation is that policymakers have some interventions up their sleeves. Monday's announcement on the 14-day rate was coupled with news that the bank would — very unusually — hold a meeting with senior officials Tuesday. That amps up speculation that more is in the works. That would make sense. Jumpstarting the economy after Covid lockdowns hasn't worked anything like as fast as Beijing wanted. The most recent economic data shows a housing sector still in the doldrums. So why wait to make a big cut in interest rates? Bloomberg Economics' Eric Zhu believes officials wouldn't want to give the impression they're taking cues from the Fed. "They may also have wanted to give July's cut more time to sink in. But we expect lenders, taking a steer from the People's Bank of China, to trim their loan prime rate further in the fourth quarter." As it is, the currency market has responded by bidding up the yuan to its highest levels against the dollar in 16 months, in a move that continued after Monday's announcement on the 14-day rate: Gavekal Research's Wei He argues that the Fed's pivot should be good news for the PBOC as it will be less constrained by concerns that lowering rates would intensify capital outflows and weaken the currency. He suggests this isn't the main factor keeping them from lowering rates: For most of the first half, it was trying to defend a de facto currency peg against market pressure for the renminbi to depreciate; cutting rates would have made that job harder. The surge in the yen since July has taken that pressure away.

The yen's recovery since the summer has made the yuan, or renminbi, much more competitive: Meanwhile, the pessimism surrounding China's growth target gets worse with every disappointing economic data print that suggests the solid start to the year was an aberration. Policy support is urgent if Beijing is to achieve its 5% growth target. Lower lending rates would put some life back in the consumer, and Zhu is convinced that the Fed cut brings that a step closer. After its dovish statement citing "supportive monetary policy," rates are only headed down. That would provide commercial banks with more wiggle room to reduce interest costs. So what might be in the cards? China's broader plans center on "new productive forces." Basically, Xi Jinping wants resources to be shifted from real estate, which is in bad shape, to manufacturing, where there should be an abundance of high-productivity jobs. The PBOC, like other agencies, is driven by this top-level political focus. As a result, Gavekal's He believes that the PBOC's recent attempts to enforce a type of yield-curve control in the government bond market are now called into question. The benchmark 10-year China bond, currently yielding around 2.03%, is sagging under the weight of investors' gloomy economic outlook. It sits below the PBOC's implicit 2.1% floor set only in August: He argues that it's unclear whether the PBOC has simply given up on long-term yield curve control, or whether it will try to defend yields at a lower level: If the PBOC does intervene in the bond market again, it will be harder for it to enforce a particular level of yields, as market participants will doubt its resolve. The PBOC's decisions have thus created more uncertainty and… failed to prevent long-term bond yields from falling. With nominal growth lackluster and little additional stimulus from government policy, 10-year bond yields could soon go below 2%.

The distress signals are ever harder to ignore. The limited progress from the relatively sparse policy support measures underscores the need for urgency. Beijing has a game plan, and maybe we are about to learn a lot more about it. —Richard Abbey It turns out that there are lots of songs about stars, even if not precisely about R-Star. Try Lucky Stars by Dean Friedman, Starry, Starry Night (Vincent) by Don McLean, Stars by Dubstar, My Star by Ian Brown, We're Stars by Hear'n Aid, Star Sign by Teenage Fan Club, Guiding Star by Cast Underneath the Stars by The Cure, Sky Full of Stars by Coldplay, Antistar by Massive Attack, "War" by Edwin Starr, "You're Sixteen, You're Beautiful (And You're Mine)" by Ringo Starr, "Can't Wait Another Minute" by Five Star, Star by Primal Scream and Lucky Star by Basement Jaxx, and Shooting Star by Bad Company. The Grateful Dead's "Dark Star" was legendary; here are versions from 1969 and 1974. There must be more stars where they came from? Have a good week everyone and enjoy September while it's here.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Matthew Yglesias: Harris' Most Important Plan Is Unknowable

- Adrian Wooldridge: A US Soft Landing Will Rest on Increasingly Shaky Ground

- Marc Rubinstein: US Counts Its Bank-Bailout Billions While Europe Still Nurses Losses

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment