| I'm Chris Anstey, an economics editor in Boston, and today we're looking at how Japan's demographics could be a stimulus. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. - China's remaining growth engines are showing signs of sputtering.

- With the Federal Reserve about to cut interest rates, traders start September bracing for a terrible month.

- Labour's tax plans are hurting UK business chiefs' confidence even as private equity firms offer some support to government proposals.

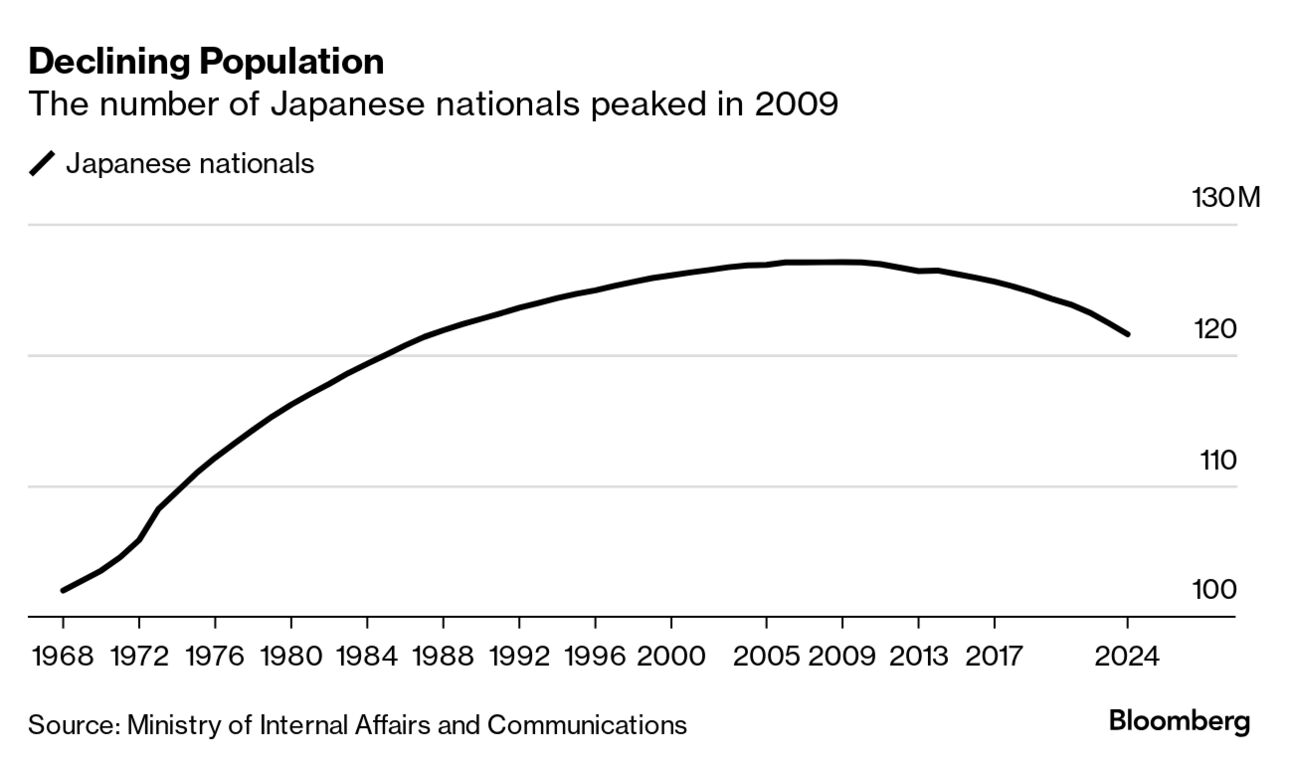

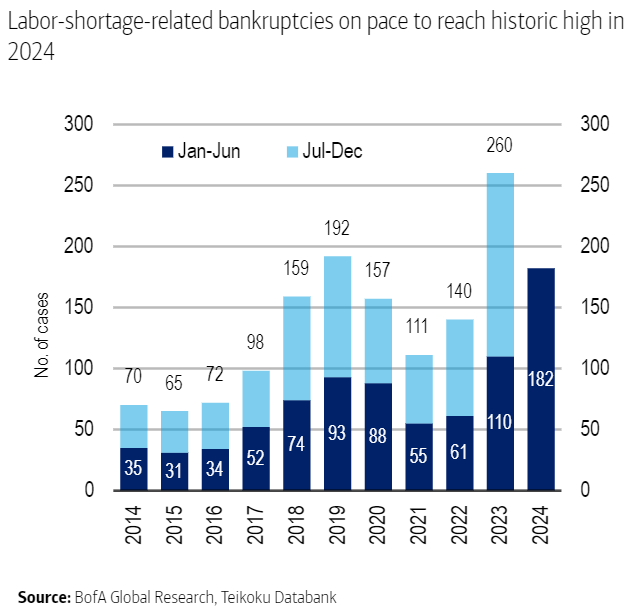

Nobody ever makes money shorting Japan. So said James Abegglen, an expert on Japanese corporate management and author of books on Japan, to a Columbia Business School audience around 1993. Oops. From 1992 to 2002, the Nikkei 225 Stock Average handed investors a loss of 46%. (The S&P 500 earned 142%.) Abegglen was among many who failed to see the long-term impact on Japan's economy from its massive asset-bubble collapses and its demographic decline. But now, a new set of structural forces are combining, potentially, to make "going long" on Japan a reasonable play. That's according to Bank of America economists and strategists, in a recent note to clients. First off, demographics. The country's shrinking population is set to have far-reaching effects. A not-obvious one: faster productivity growth. The argument here is that, as companies struggle to hire workers, they will be incentivized to step up capital-goods investment that boosts the output of those workers it has. Fewer people to fill job openings will also put upward pressure on wages. In fact, it already is — base salaries just climbed by the most since 1993. And that's setting off a sort of Darwinian competition among Japan's companies. In the end, those that aren't efficient and profitable enough to pay their workers more will go under. There is already evidence of "a healthy culling of firms that cannot keep pace," BofA economists Izumi Devalier and Takayasu Kudo wrote. They cited data showing "labor-shortage related bankruptcies nearly doubled in 2023 and are on track to reach the highest on record in 2024." As wages keep rising, that will help ensure Japan's long-held deflationary mindset is gone forever. And as Japanese households and businesses get accustomed to inflation as a thing, it will reshape behavior in countless ways. Last week, Japan's financial regulator said it's going to take a look at how major banks manage risks in this new "world with interest rates." For households that have long kept more than half of their vast pool of savings in cash, hundreds of billions of dollars worth of it literally in banknotes, inflation will make it more worthwhile to invest in higher-yielding assets, such as stocks. Things might not change so much for older generations, but BofA analysts highlighted that securities buying has been propelled by people in their 30s and 40s — who don't really recall the bubble implosion. Companies, too, are massive holders of cash. Private nonfinancial firms were sitting on the equivalent of roughly $2.4 trillion earlier this year. Pressure will rise to invest that cash or return it to stockholders. In a worst-case scenario, Japanese firms, conditioned to thinking domestic growth prospects are limited, focus on deploying investment abroad. That would mean "further hollowing out of the economy," the BofA team cautioned. The hope is that as businesses set aside models dating from the deflationary era, productivity can gradually pick up. - China threatened retaliation on Japan chipmaking equipment export curbs, and South Korea wants US incentives to comply on restrictions.

- New data on UK wages are raising awkward questions for both Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey and Prime Minister Keir Starmer.

- Turkey's economic growth slowed both in quarterly and annual terms through June, highlighting the impact of higher borrowing costs.

- South Korea's export growth returned to double digits last month, reflecting a resilience in global demand for tech products.

- Brazil's government expects to make a "true spending review" next year with a focus on achieving its 2026 fiscal target, a minister said.

- Israelis began large labor strikes in the strongest push yet to force Benjamin Netanyahu's government to accept a cease-fire with Hamas.

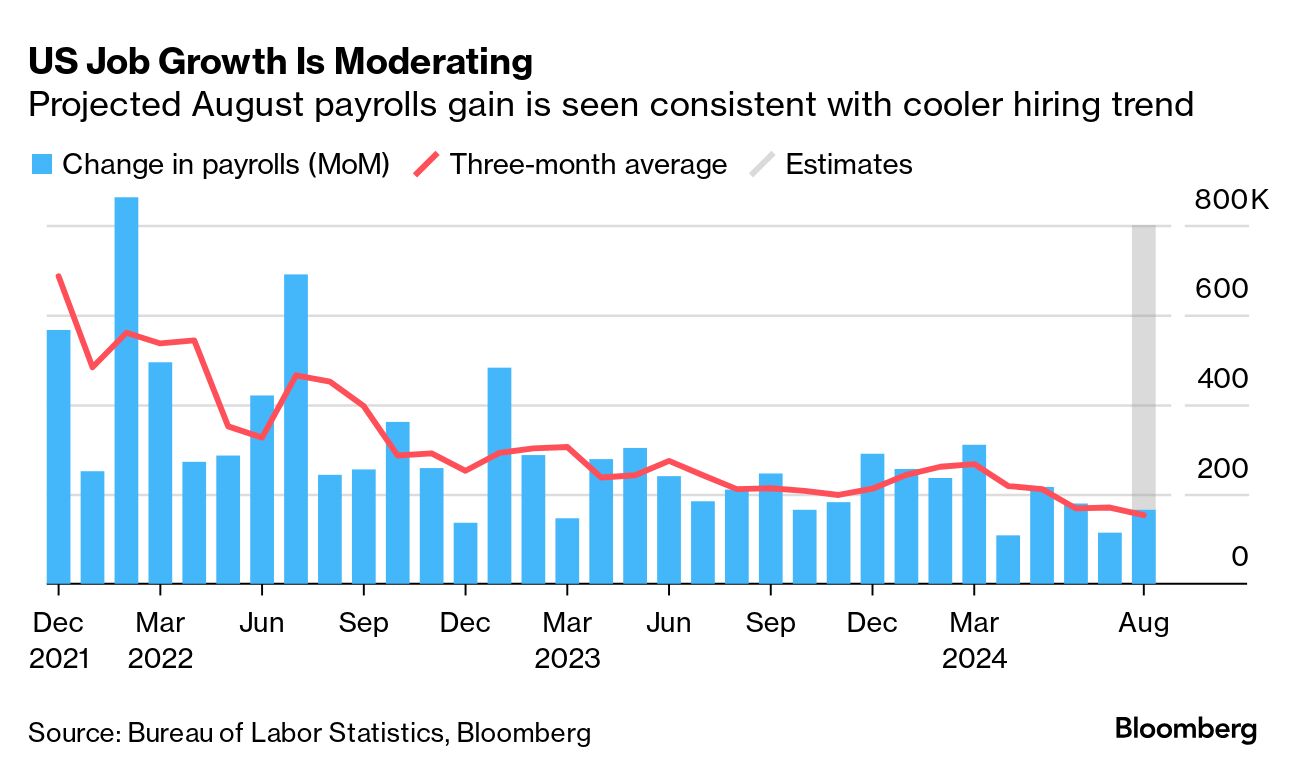

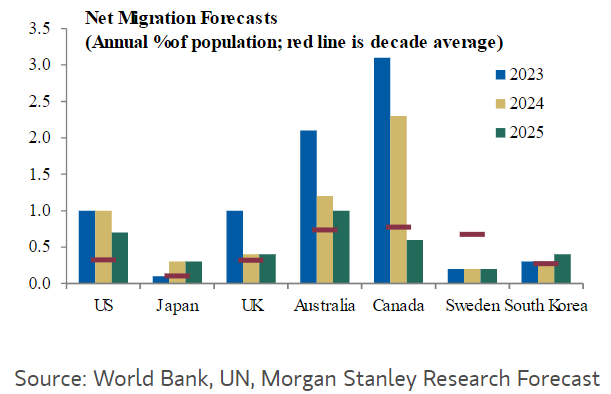

Upcoming readouts on the US labor market, including the monthly payrolls report on Friday, will give Federal Reserve policymakers insight into the need for further interest-rate reductions after an all-but-certain cut in a little more than two weeks. Elsewhere, the Bank of Canada is widely expected to deliver a third straight rate cut, as inflation that's been within its target range all year allows officials to shift focus to weakness in the job market. See here for the rest of the week's economic events. Immigration affects both supply and demand, and the mix can be different depending on a number of factors. For instance, if newly arrived workers remit a lot of their income to their home nations, that lessens the demand impact in their new home country, Morgan Stanley economists point out. Different countries have had differing impacts. In the case of Australia, an historic influx of immigrants in 2023 — that added 2.1 percentage points to population growth — proved inflationary. Consumption and housing demand climbed, and the supply side of the economy couldn't keep up, economists led by Seth Carpenter wrote in a note last week. As immigration slows, effects will also be different across countries, the Morgan Stanley team said. In the US, an abrupt tightening in migration could boost inflation because of the impact on labor supply. In a place like Australia, "where demand effects have been more significant, inflation might be kept in check, but consumption would likely suffer, meaning weaker growth but lower inflation." |

No comments:

Post a Comment