| It would appear that prediction markets are among the biggest winners of the US political season. Niall Ferguson even argued in the Wall Street Journal that their "success in calling the 2024 election" will "bring an end to the era of political forecasting as we know it." It was illustrated with a cartoon of a large whale (like the "Trump whale" whose big bets moved the odds on Polymarket) taking the well-known polling aggregator Nate Silver in its jaws. As Ferguson said: The rise of prediction markets is inseparable from the broader decline of experts across many fields. In the same way that Elon Musk has declared to the users of X that "You are the media now," Polymarket tells its users that they know better than the pollsters.

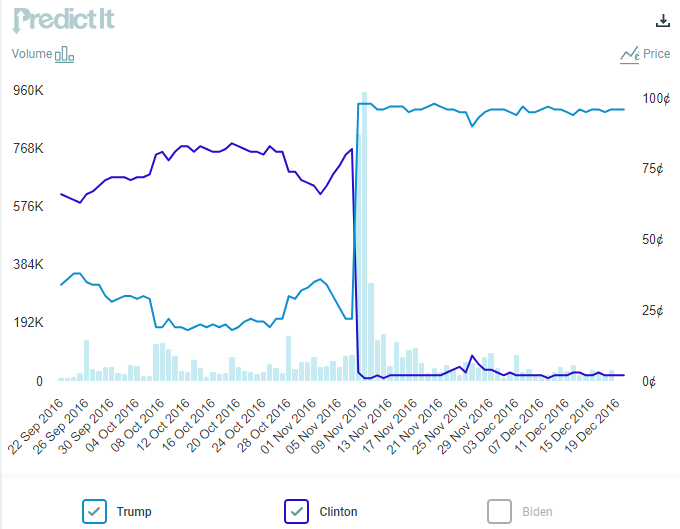

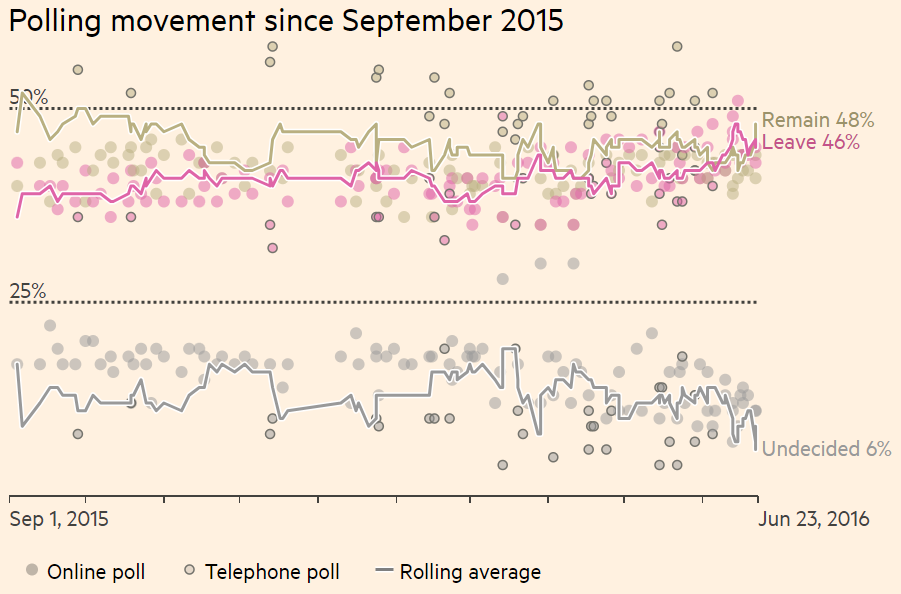

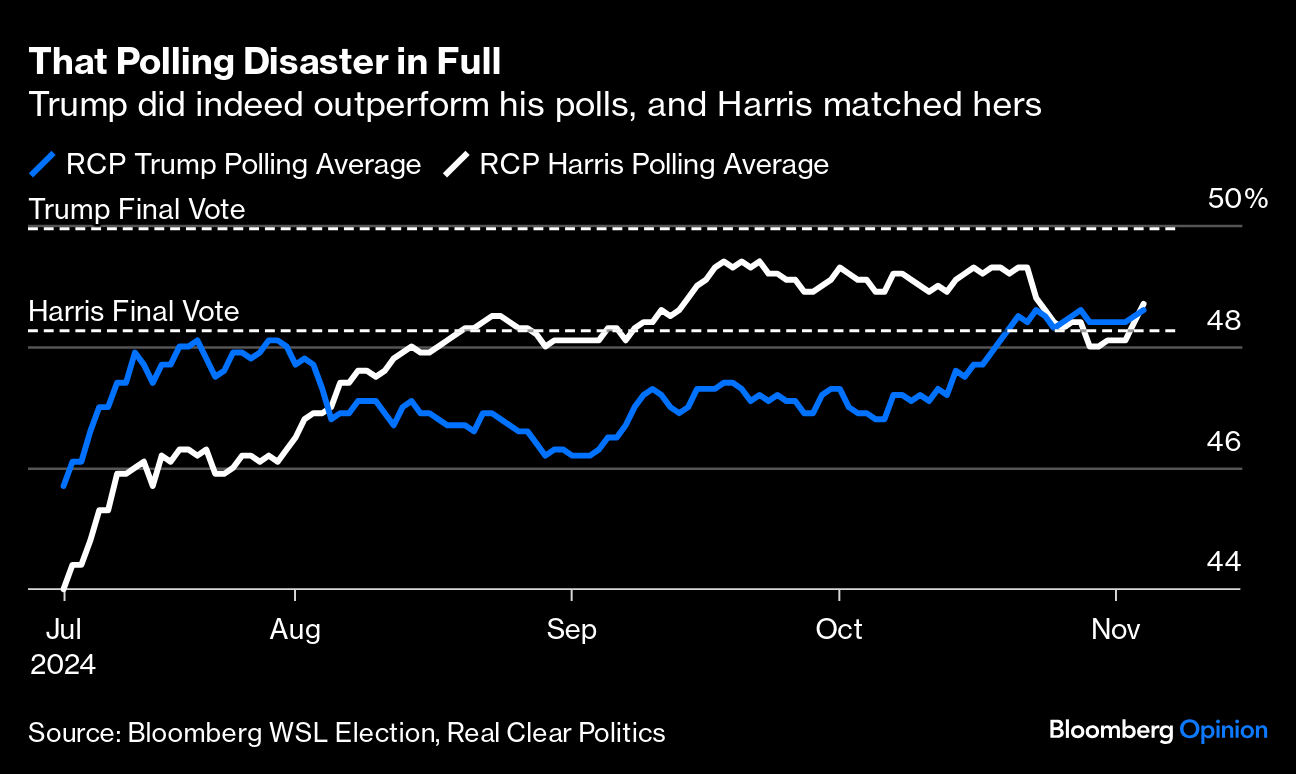

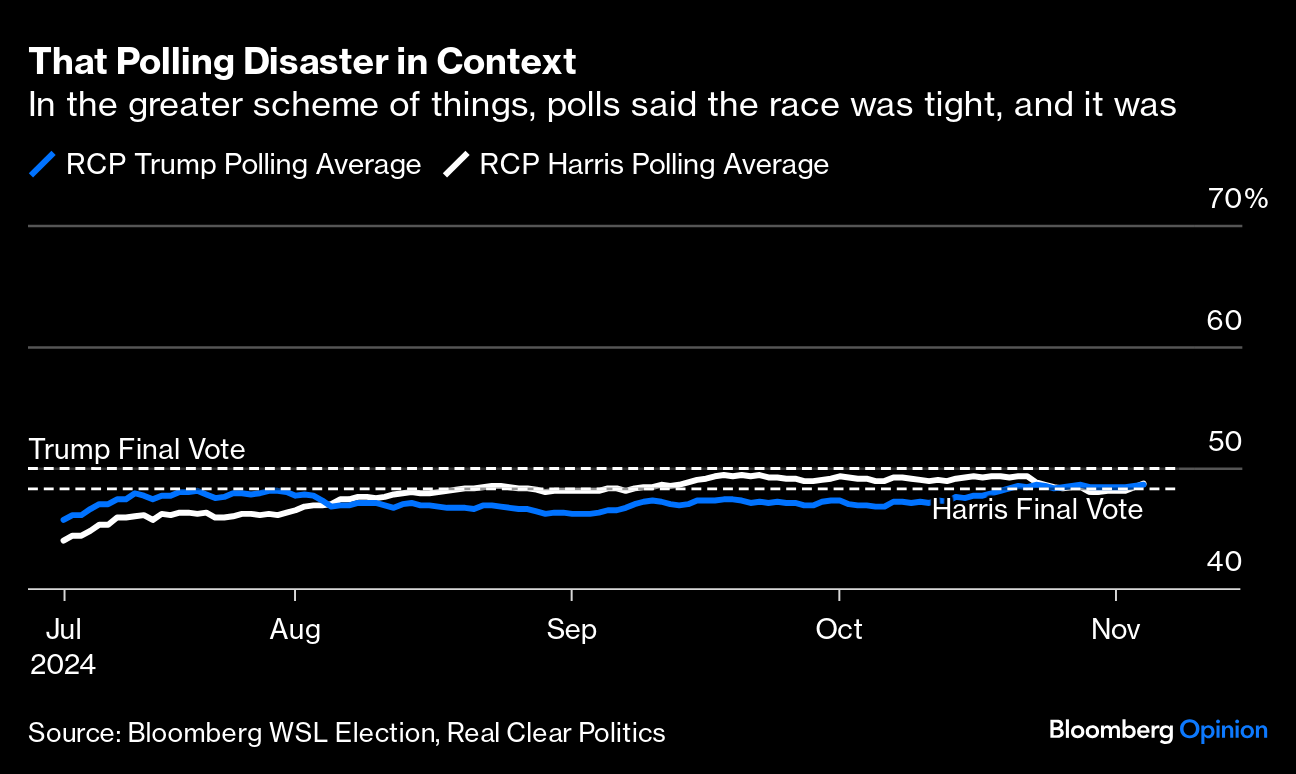

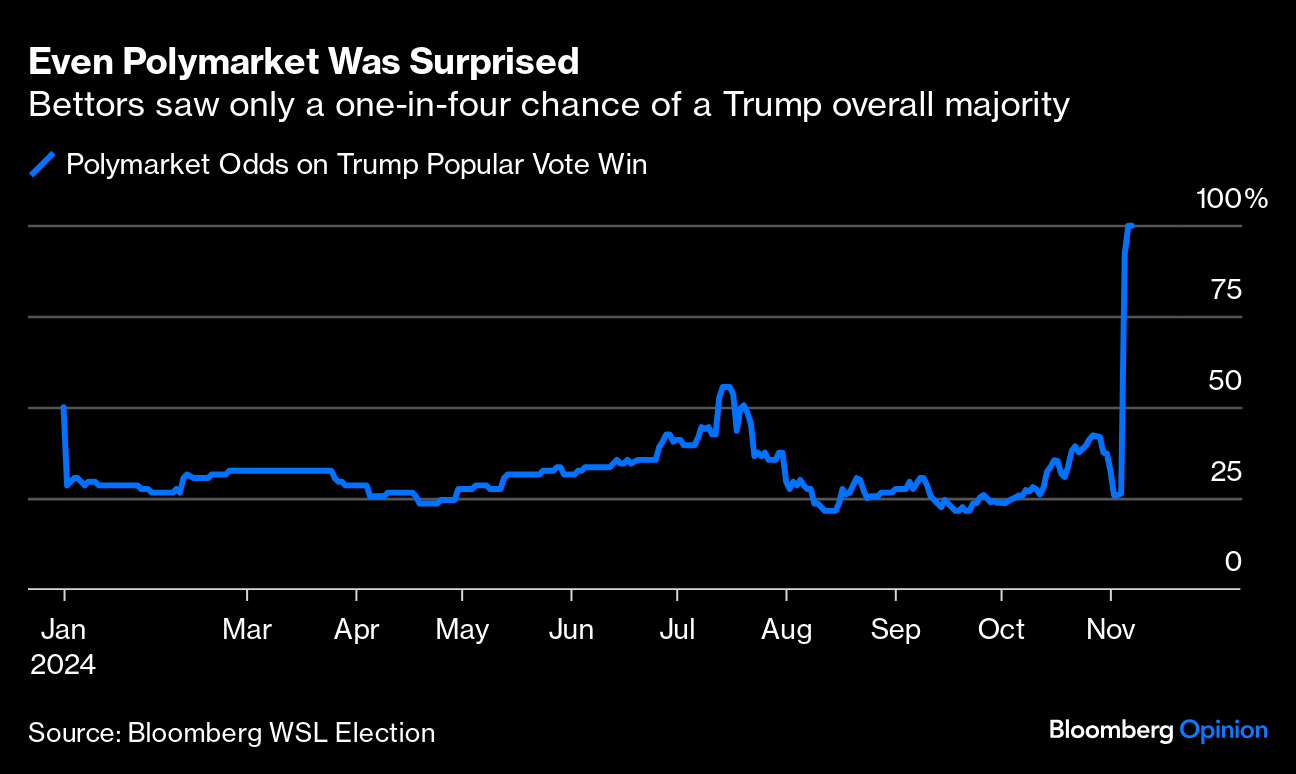

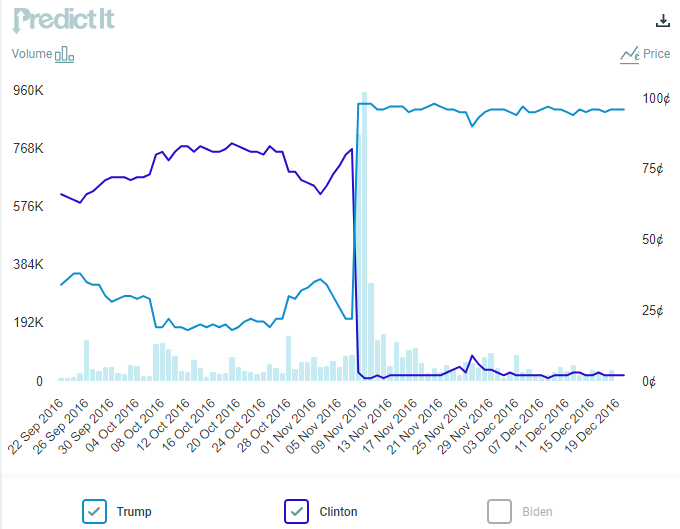

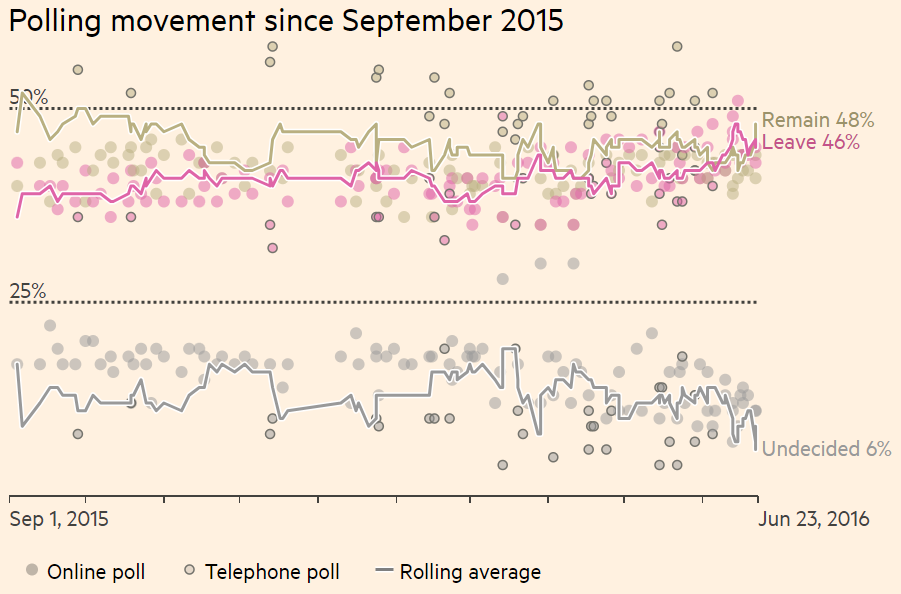

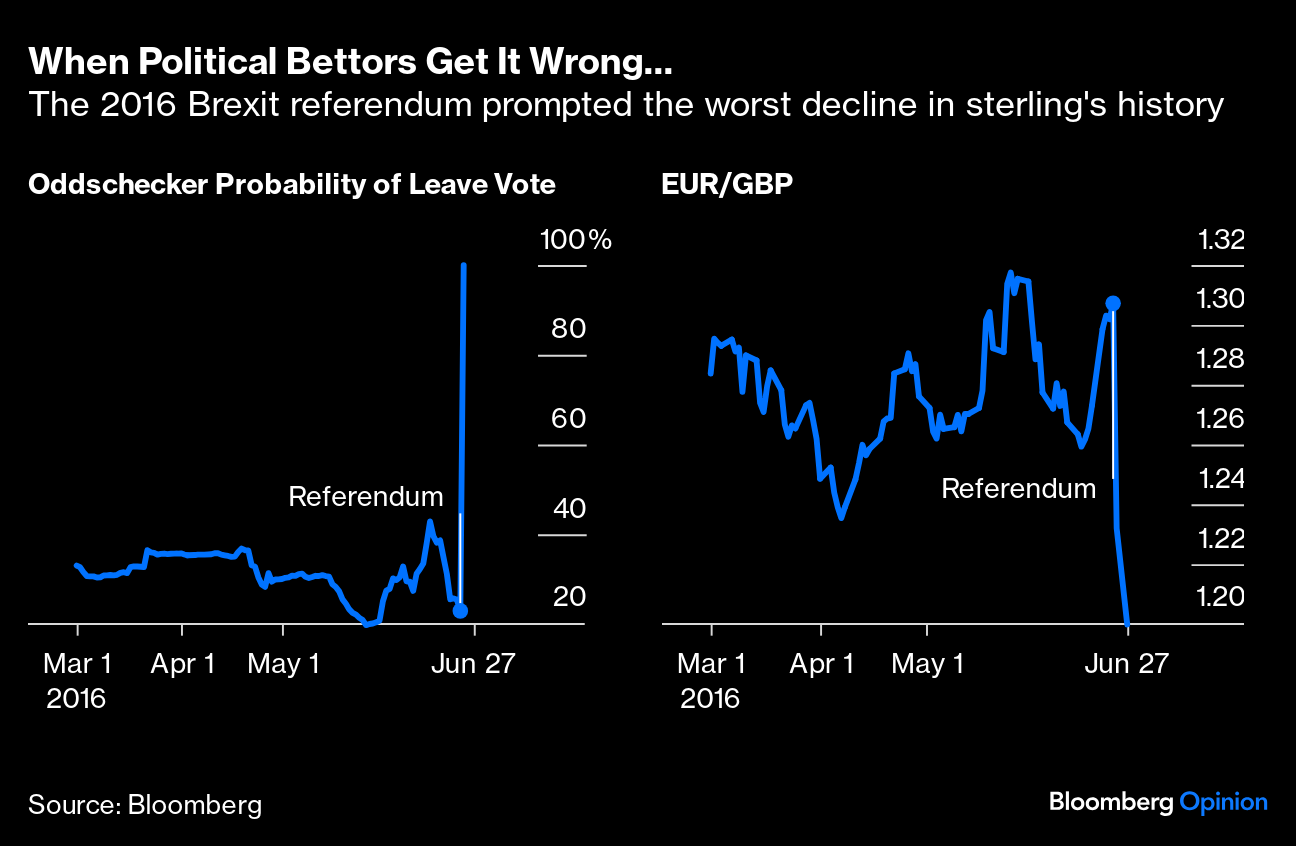

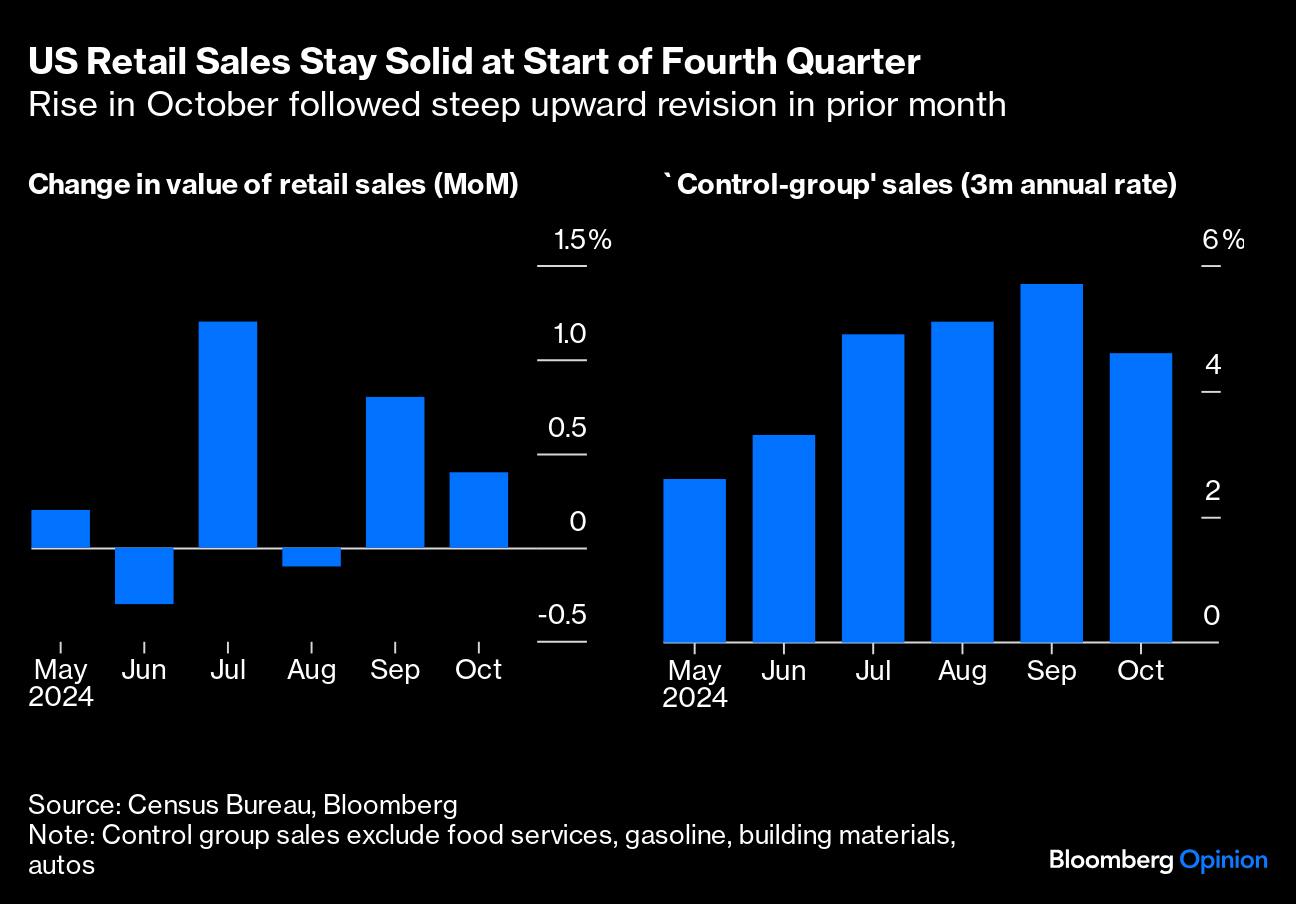

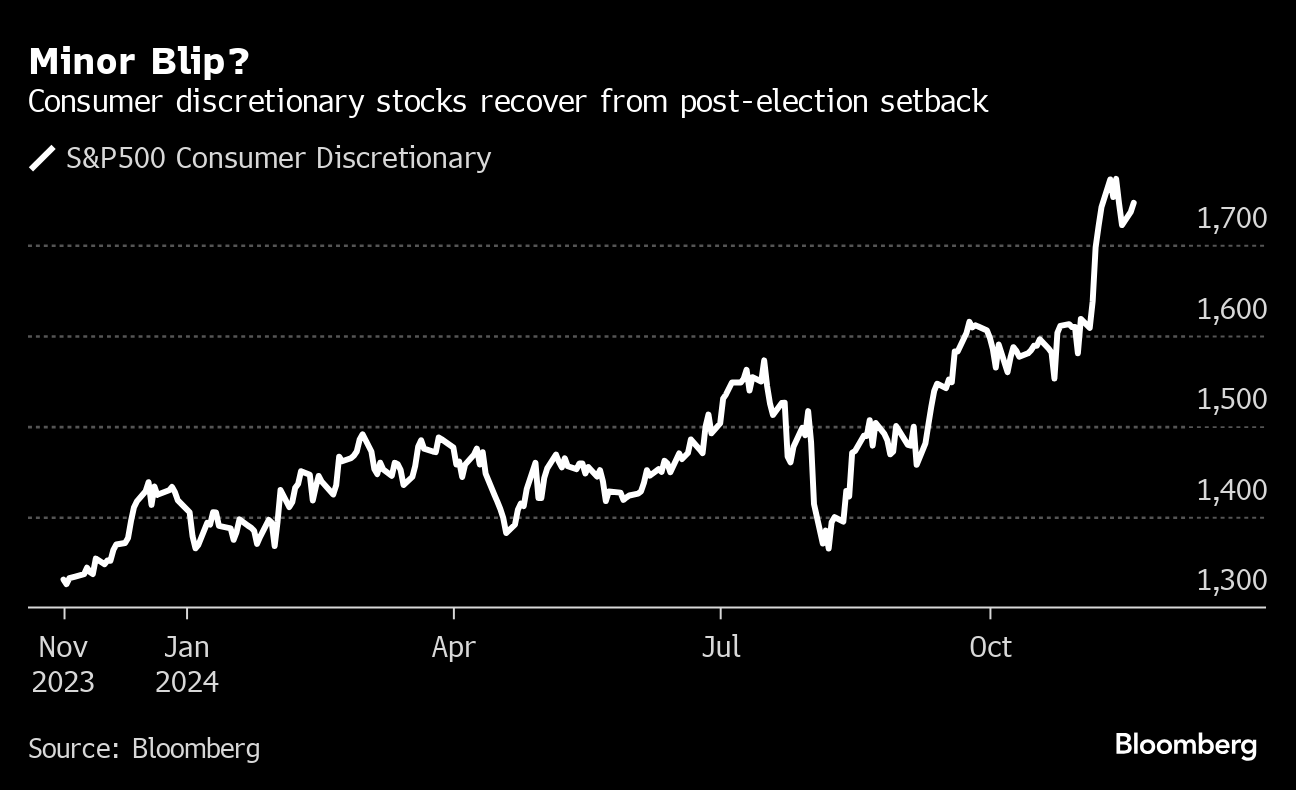

I'm aware that nuance is out of fashion when discussing politics, but I would like to add some. For more measured takes, try the response in the New York Times from Silver himself (headlined, "Polling is not the Problem"), and Bloomberg Opinion colleague Lionel Laurent, who avers with total accuracy in my view that "platforms like Polymarket had a good election, but the hype is overdone." For a stronger take, try Dennis Kelleher of BetterMarkets' "Prediction Markets did NOT Nail the 2024 Election." I'm tempted to say that calling such an emphatic victory for prediction markets on the basis of one result is akin to what Wall Street calls the Elaine Garzarelli Effect, for the equity strategist who famously told clients to get out of the stock market before it crashed on Oct. 19, 1987. However, there is a crucial difference. Garzarelli was feted and later proved fallible — like everyone else — but she did get the Black Monday call spectacularly right. That isn't true of prediction markets in 2024. It actually wasn't a very good election for them by their own historical standards. First, Did They Really Call It? To look at this in detail, the argument that the prediction markets — particularly Polymarket, which is based on the blockchain and basked in Elon Musk-assisted publicity — called the election correctly rests on the fact that they ranked a Donald Trump victory as likely (59% for Polymarket) as Election Day opened. This is how Trump's chances moved on PredictIt, a long established but less liquid exchange, and Polymarket over the last year:  Polymarket "called" the election, but its bettors thought that Kamala Harris would emerge victorious slightly more than 40% of the time. That's little different from perceiving it as a coin flip. Few would be comfortable betting much on anything where they would lose four times out of 10. Sometimes, prediction markets can and do put election odds at more than 90%. From the beginning of October, Polymarket had the chance of a Democratic victory for the North Carolina governorship — where the Republican candidate was hopelessly mired in scandal — at 95.5%. The Democrats did indeed win, with 54.9% of the vote, even as Trump captured his part of the ballot. Prediction markets wobble. This is how the odds on PredictIt and Polymarket moved in the six days before Nov. 5: Trump's Polymarket odds dropped to 52% on the Saturday, while PredictIt briefly put Harris in the lead. Nerves took hold in the face of increasingly strange behavior by Trump, and his odds plummeted after a poll by Ann Selzer — whose reputation until then gave it extra credence — found Harris ahead by three percentage points in Iowa. This was an astonishing outlier, and turned out to be wrong. Trump won Iowa by 15 points. The important thing is that it moved the prediction markets drastically, but had a tiny effect on polling aggregators like Silver, who added Selzer's poll to an average that included many others. Further, the polls didn't do that badly. This is RealClearPolitics' poll of polls starting in July. At no point was either candidate ahead by more than the standard margin of error, and the polls showed Trump gaining ground in October. The closing estimate for Harris was almost exactly accurate, while Trump was underestimated by almost two percentage points: The idea that the polls were "wrong" rests on the fact that they showed Harris was very slightly ahead at the end, and she in fact lost the popular vote. However, these numbers were consistent with a Trump victory given the nature of the Electoral College. Harris' margin was at all times narrower than Hillary Clinton's over Trump eight years earlier, so it was perfectly consistent to take these polling results, along with numbers from the swing states, and name Trump the favorite. It's odd that bettors weren't prepared to put more money on it. For broader context, this is the same chart, but on the same axis as the probability chart, from 40% to 70%. Pollsters said the electorate was tightly balanced and that few people were changing their minds, which was right: One more issue is that the polls showed a dead heat in the popular vote. Prediction markets thought Harris was clearly favored — yet Trump won it. How is this consistent with the claim that its bettors successfully called the election? 2016 And All That Then there are the great surprises of 2016, when Britons voted to leave the European Union and Americans voted in Trump for the first time. Both are regarded as terrible failures for the polls. That's fair, but prediction markets did worse. This is how PredictIt (Polymarket wasn't around at the time) saw the Trump-Clinton contest. Trump's odds stood at 22% on election eve:  Source: PredictIt For comparison, Nate Silver, then plying his trade for Fivethirtyeight.com, put the odds of a Trump victory at 33.1% (a fact for which he's criticized by Ferguson). So a polling aggregator gave Trump a one-in-three chance and rated his chances more highly than the prediction markets. That's not so bad. The Brexit referendum was a truly bizarre failure for the prediction markets. Here is the poll of polls produced by the Financial Times, where I was working at the time, for the nine months leading up to the vote:  Source: Financial Times "Leave" steadily gained and even nosed ahead at one point. A few polls restored Remain's lead right at the end, but it looked like a knife-edge. This, however, is how the betting markets as aggregated by Oddschecker saw it, and the effect that the electoral misjudgment had on the pound: I have no idea what induced people to bet so confidently on a victory for Remain, but they were wrong, and they were not following the polls. How Prediction Markets Won Prediction markets won in 2024 in that they gained attentiom, obtained some legal victories over the regulators, and oversaw far greater volumes than before; Polymarket's reported volume of more than $1 billion dwarfs what had been seen on smaller experimental markets in recent decades. Regulated onshore political markets are in all probability part of our future. The discipline that they add in interpreting polling evidence with money at stake is useful in making predictions, and also in gauging what probabilities are embedded in other markets. As I've written, they have a long history of producing good results. But it's absurd to suggest that they've put polls out of business. Somehow, someone needs to survey public opinion if they want to predict the result of an election. The ways pollsters do this don't work as well as they used to and should be changed. But you need some information to aggregate. And as markets are prone to overshoot, and people have an interest in manipulating them, they must be well regulated. Used with polls as a basis, prediction markets will generally come up with slightly more accurate predictions than polls on their own. They have a place. But no, the 2024 election doesn't show that prediction market bettors know better than the pollsters, or that we can do without opinion polls. The post-pandemic resilience of the American consumer is almost like wine — it gets better with time. October's retail sales data backs the narrative of a continuing splurge ahead of the holiday season. The latest print topped consensus estimates and the prior month's figures were sharply revised. Glenmede's Jason Pride describes the consumer as a V8 engine firing on all cylinders, and retail traffic volumes in the coming weeks should come in even stronger. This chart offers a baseline for the upcoming holiday season: But what happens to consumer sentiment after the post-election bounce wears off? They will tire at some point, and there are several potential triggers. For now, the most visible headwinds are political, as Trump prepares to return to the White House. His promised tariffs on imports and spending cuts will impact consumer spending. Strategas' Dan Clifton forecasts spending cuts in areas such as Medicaid, food stamps, and student loans, and finds high correlation between these programs and both retail sales and the relative performance of consumer discretionary stocks. As shown from this chart, the sector survived a minor setback after the election; it's unlikely to keep rising sharply if spending slows: Clifton suggests that getting Trump's cuts over the line will be challenging: Republicans are eying food stamps and Medicaid savings to extend the tax cuts. Passing offsets to the tax bill will not be easy in a polarized Congress, and cutting government spending with powerful interests, such as the farm lobby, makes it even more difficult. But Republicans are pushing to bring these programs back in line with pre-pandemic levels following a Covid surge.

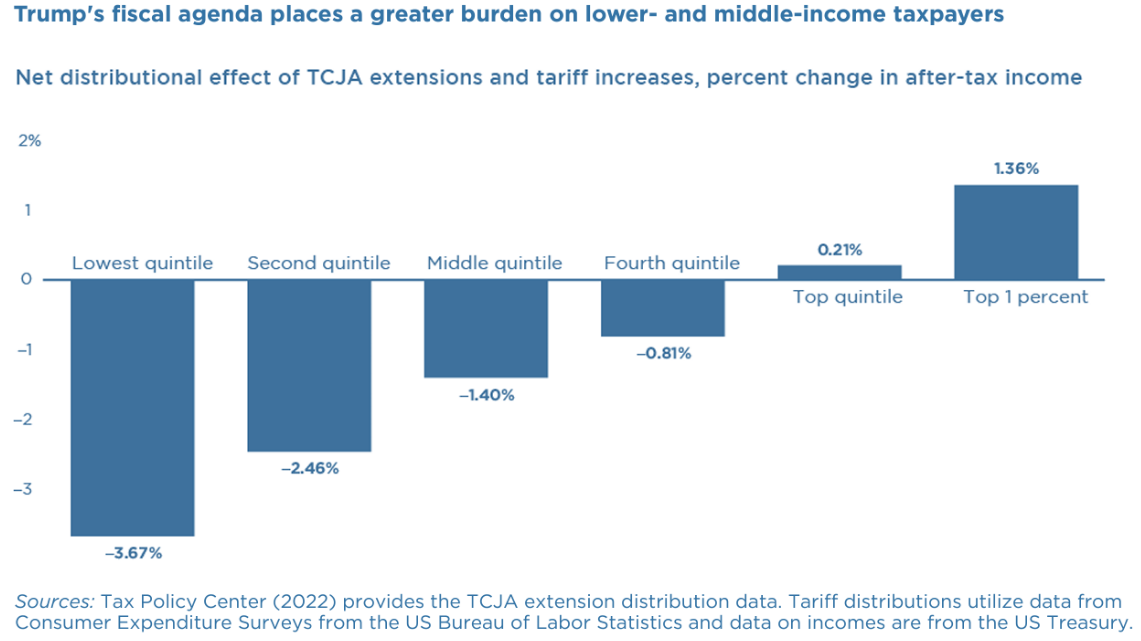

Trump's obsession with tariffs on imports also carries significant risks. For starters, there is a possibility of importers shifting the tax burden to consumers. The 50% tariff on imported washing machines in 2018 offers insight on how this could work. This paper published in the American Economic Review found a 12% jump in the average price of washing machines as a direct consequence of the tariff — equivalent to $86 per unit. What may be intended to benefit citizens seeking jobs and better pay might end up hurting them as consumers. It's also possible that lessons learned from Trump 1.0 might help avert this pain. There's additional good cause to believe that these tariffs eventually impoverish Americans. The Peterson Institute for International Economics provides a breakdown of effects on different income levels. Unsurprisingly, the poorest fifth will suffer a 4% loss of income compared to 2% for the wealthiest fifth: If anything, the researchers — Kimberly Clausing and Mary Lovely — described the proposed tariff and other fiscal policies as regressive, potentially increasing both the fiscal deficit and the trade deficit, against the hopes of the incoming president. His administration (which we learned just before publishing will include Howard Lutnick as Commerce secretary) has the benefit of history in what will be a very tough balancing act. It's the 50th anniversary of Kraftwerk's Autobahn, a 24-minute synthesizer ode to the experience of driving along a German motorway. It's hypnotic, weird and wonderful, and at the time it was revolutionary. It's worth a listen, particularly in the car.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Tyler Cowen: RFK Jr. Would Put the Economy at Risk, Too

- Marc Champion: Ukraine's Allies Are Inviting Their Own 'Strategic Defeat'

- Editorial Board: Crypto's Coming Back. Here's How to Avert Disaster

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment