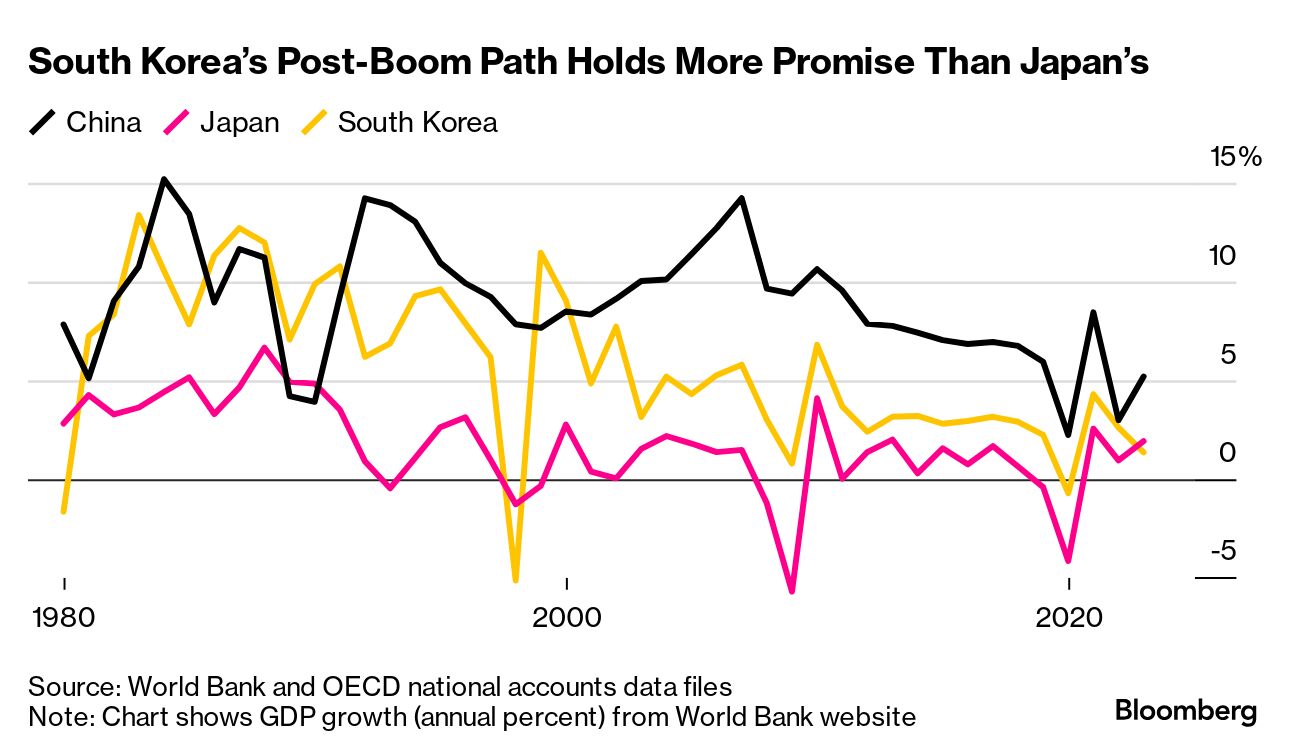

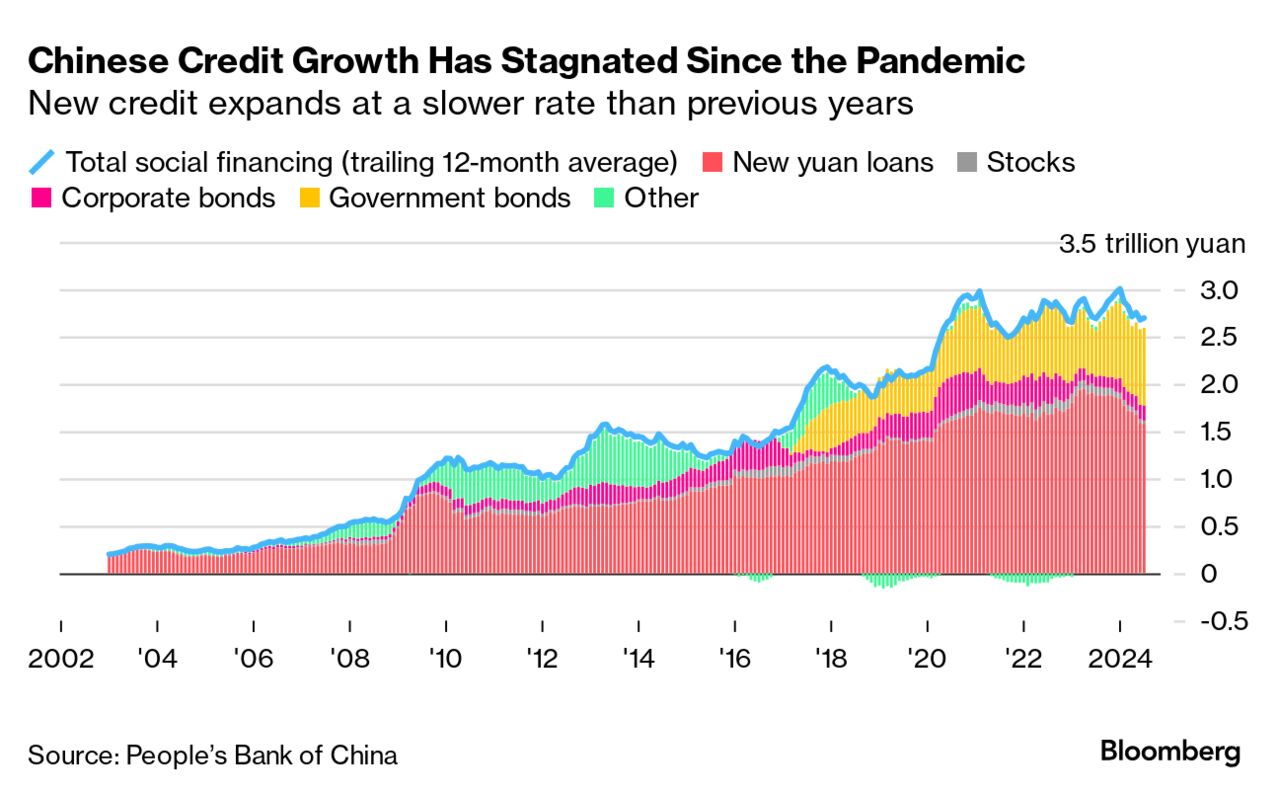

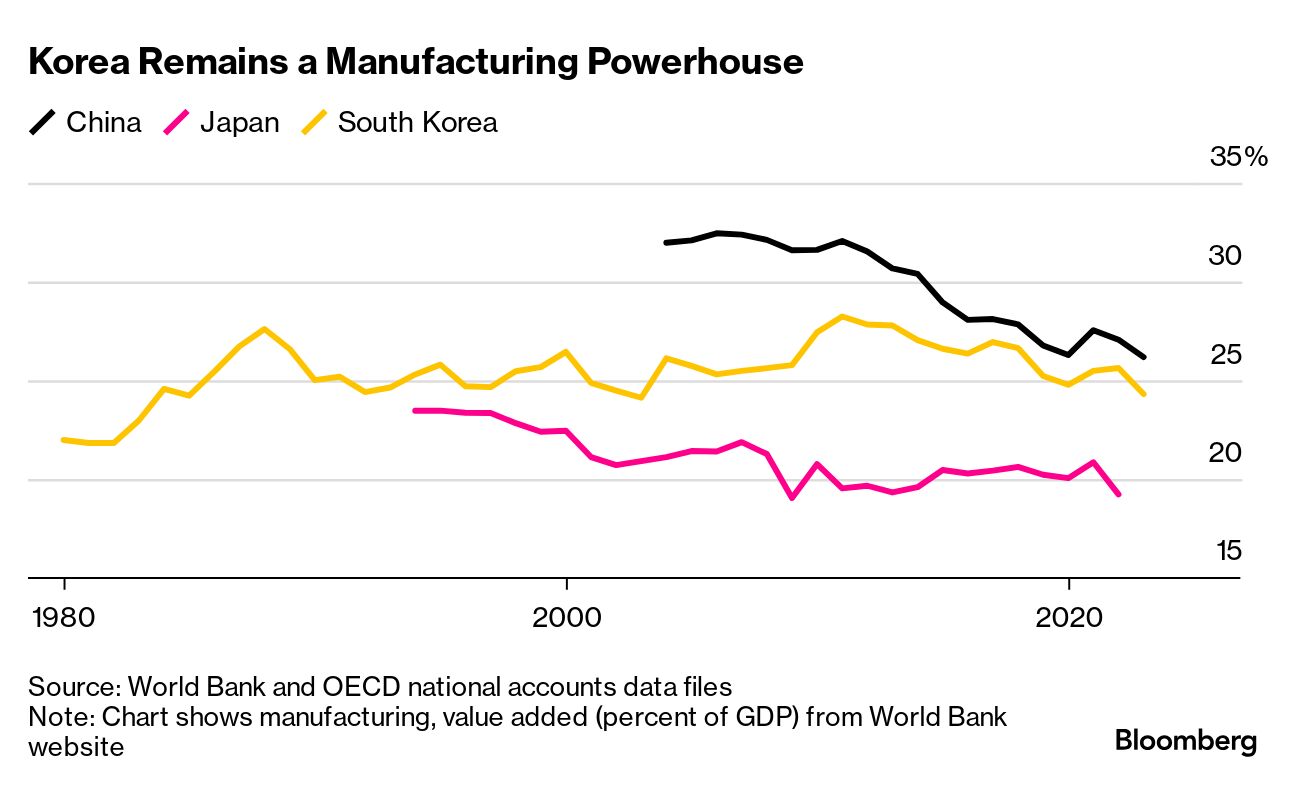

| I'm Malcolm Scott, international economics enterprise editor in Sydney. Today we're looking at China's slowdown and which Asian neighbor makes the best comparison. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. Type 'China Japanification' into Google and you'll find endless articles examining whether China's aging demographics and its real-estate slump mean that a decades-long deflationary funk is nigh for the world's No. 2 economy. Type 'China Koreafication' and the search engine queries whether you meant 'China Korea fiction.' Yet comparisons with South Korea may well be more apt than those by-now familiar parallels with Japan — which center around shared post-property bubble deflation problems and similar demographic headwinds. The Japanification narrative got more air time this week, thanks to data showing China's first bank loan contraction in nearly two decades. That, some argued, was a worrying sign that a Japan-style "balance-sheet recession" has begun. Data Thursday only added to concerns, showing an unexpected slowdown in fixed-asset investment and sluggish spending. The Japanification argument has some issues. As Chinese officials have pointed out, their country's per-capita GDP remains well below Japan's of the early 1990s — leaving plenty of room for additional catch-up growth. The key will be finding new drivers of economic growth. And that's where comparisons with South Korea come in. After decades of red-hot growth in its "Tiger Economy" phase, South Korea faced its own reckoning in the late 1990s, when the Asian Financial Crisis hit. Drawing on a long history of government-led industrial policies and an export-orientated growth model, Korea's post-crisis leaders changed tack. On the financial front, they restructured insolvent firms and improved corporate governance so similar failures wouldn't happen again. Japan, by contrast, kept its zombie firms alive, weighing on productivity and growth. Korea launched a new Industrial Development Act in 1999 that sought to shift toward an innovation-led economy and doubled down on that approach after the Global Financial Crisis and into the 2010s, with Park Geun-hye's administration in 2013 lauding the "Creative Economy." But even amid the push to boost services and knowledge-based industries, manufacturing retained its share of the economy as factories moved up the tech value chain and boosted exports — something Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and its predecessor struggled to achieve. Jumping forward to modern-day China, President Xi Jinping is promoting "new productive forces" and the quest for "high-quality growth" — much like his Korean predecessors did. And he's seeking to remove some of the old guarantees for state-linked companies. Of course, the China-Korea comparative also has its flaws. For one thing, China has reduced its reliance on exports since the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis highlighted the risks of relying on global demand, whereas Korea remains more export dependent. And comparing any two economies is problematic, let alone a giant like China with neighbors that have populations similar to some of its coastal provinces. But if comparisons must be made, then Koreafication is worth at least one entry into Google's algorithms. - Desperate for a chance at a new beginning, migrants are paying tens of thousands of dollars for mainly low-level jobs in Canada.

- China's central bank chief pledged further steps to support the economic recovery, while cautioning that it won't be adopting "drastic" measures.

- UK retail sales bounce back after discounts drive spending.

- Australia's central bank remains some way off easing monetary policy, Governor Michele Bullock said, as inflation is proving persistent.

- Indonesian President Joko Widodo used his final budget to both secure his legacy and the support of incoming leader Prabowo Subianto.

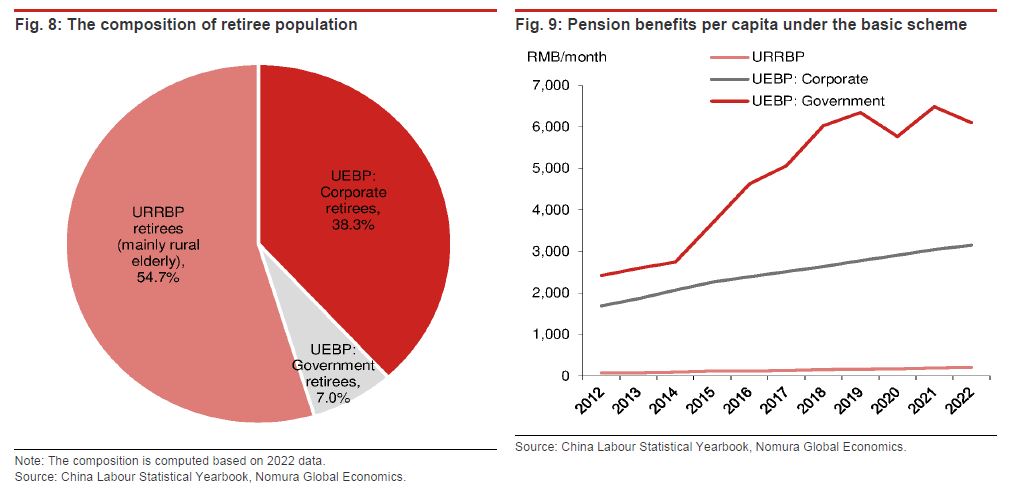

One thing China shares with both Japan and Korea is a rapidly aging population. And a special report from Nomura economists this week offers insight into how this is posing a drag on consumer spending. Particularly important is the income available to older-age Chinese. - Pensioners who had worked in government tend to retain most of their pre-retirement wages, but they constitute only 7% of overall retirees

- Corporate employees, making up 38.3% of retirees, lose around half of their income after retirement

- Rural elderly (including former migrant workers) account for 54.7% of retirees and their incomes plummet. Their benefits are just 6.5% of corporate pensioners and 3.4% of government pensioners

Weak pensions aren't just a problem for consumption upon retirement. As the "permanent income hypothesis" argues, when people expect a post-retirement income drop, they tend to save more and consume less before they hang up their boots too, the Nomura team, led by Lu Ting, wrote. |

No comments:

Post a Comment