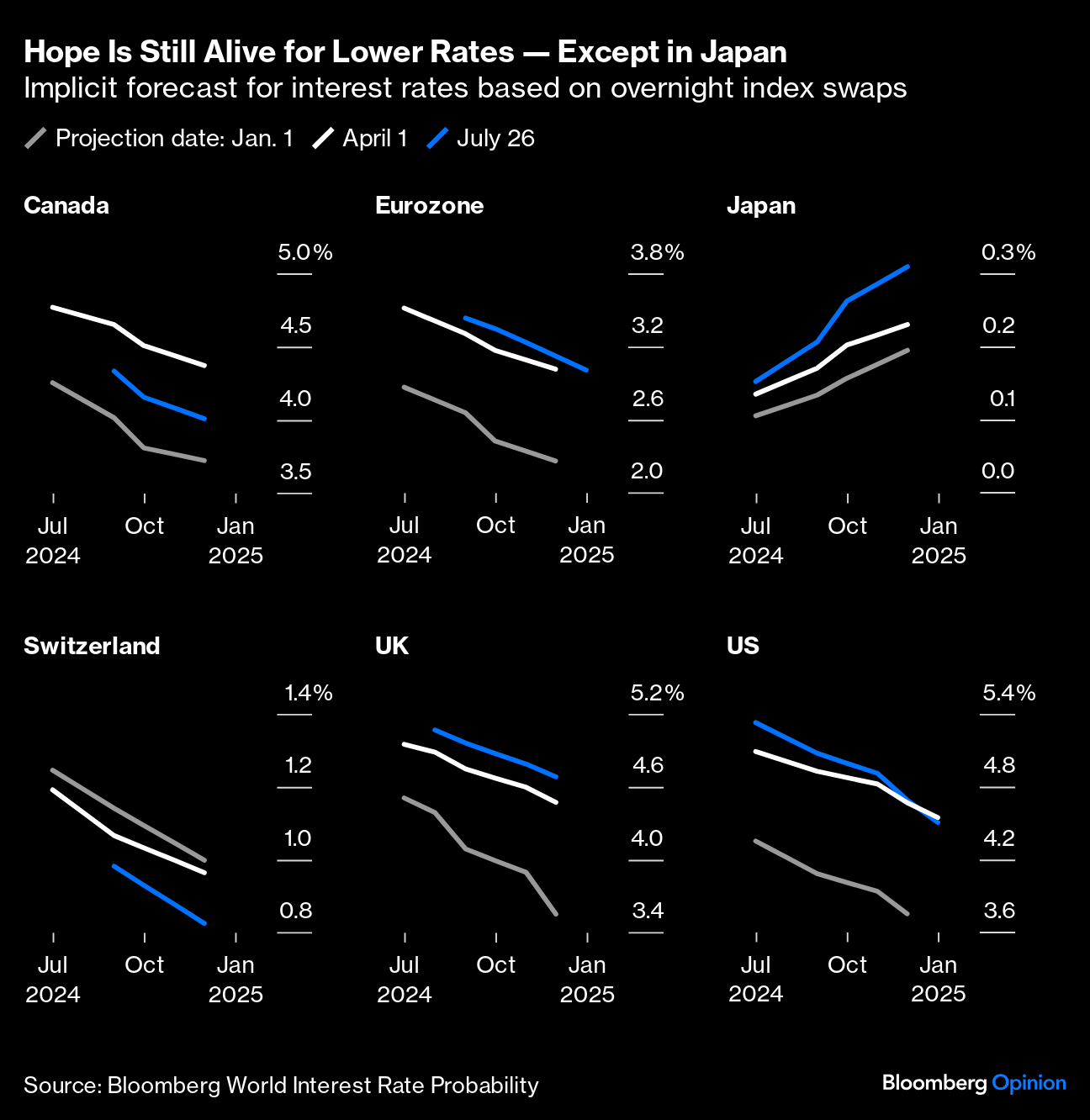

| Exactly a year after its last rate hike, a good run of economic data has the Federal Reserve closing in on its first cut since March 2020, but it's still not clear when it will happen. Markets are more than 100% certain of a quarter-basis-point cut in September. But coordinating between central banks remains perilous. In a 32-hour period on Wednesday and Thursday, the Bank of Japan, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England will all meet to decide on monetary policy, and it's quite possible that each will move in a different direction. The emerging story of other global central banks' attempts to make a descent from peak interest rates — which we collate in this latest installment of The Year of Descending Dangerously — shows that moving will be difficult. The hope for imminent policy loosening comes with some déjà vu. The Fed's infamous pivot toward easier rates late last year and the subsequent re-acceleration of inflation provides a cautionary tale, and it doesn't want to be fooled again. As Points of Return tracks the descent from high rates, the obvious question is whether the Fed's so-called "greater confidence" required to ease is finally within sight. Several Fed speeches, and multiple data prints, since our last installment show clear progress toward the Fed's inflation target. That has revived hopes for rate cuts in the US and across developed markets. Strong belief in a September fed funds rate cut aligns with expectations from developed peers, including Canada, Switzerland, and the European Central Bank, as shown in the chart:  These numbers come from Bloomberg's World Interest Rates Probabilities function, which derives implicit policy rate probabilities from futures and swap prices. With the seemingly eternal exception of Japan, rate cuts are expected across the developed world, although the direction of travel is different. In the UK, the eurozone and the US, there is less optimism about cuts than back in April; in Switzerland and Canada, where cutting is underway, expectations have reduced. Those differences are largely because the economic data remain ambiguous. Strong US second-quarter gross domestic product growth came amid fears of recession. Although growth topped analysts' estimates, the data remained consistent with a gradual slowdown. Others face a more urgent need to ease policy. What to do? As with scaling mountains, coordination is vital in monetary policy. Mountaineers find safety in roping themselves together. As the Fed has yet to begin its descent, peers that have commenced theirs cannot move too far ahead. Otherwise, they risk a run on their currency. Persisting high US bond yields have piled the pressure on to emerging market currencies in particular: Much though most emerging central banks would like a fed funds cut this week, what's more feasible Wednesday is a detailed communication of the path to a cut in September. In the interim, there will be a raft of data downloads, including inflation for July and August. The Fed can buy more time awaiting this data showing an additional path of prices, suggests Jeff Schulze, managing director, head of economic and market strategy at ClearBridge Investments. The inaugural piece in this series highlighted that developed-market central banks moved late, compared to emerging markets, as inflation rose after the pandemic. They paid the price with steeper rates lasting longer, while many emerging central banks could start cutting. With economic growth now slowing, central banks in Switzerland, Sweden, the eurozone, and Canada have all made the jump to ease policy, without waiting for the Fed. They are not oblivious to the pressure high rates in the US put on local currencies — increasing the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debts for these countries, and prompting a flow of of capital to the US — but they have started the descent. The latest shift in US rate expectations is heartening central banks elsewhere; they have one less thing to worry about. Several developed markets, including Canada and Switzerland, have cut more than once. That in turn helps to boost rate-cut optimism in the US. The international trend is clearest in the latest edition of our diffusion index, in which rate cuts or hikes by each of 57 central banks count equally: Last month saw a net 10 cuts across the world, easily the most since the pandemic. The following chart shows where rates have declined since our last publication June 10. It's a broad mix of countries spanning developed, emerging, and frontier markets: The Fed is increasingly an outlier. Globally, disinflation is becoming commonplace. Slower price growth takes place as commodities lose steam amid poor demand, strengthening the case for monetary stimulus in emerging economies that depend on commodity exports. Overall, developed and frontier markets have caught up with emerging peers; they are now just as likely to be cutting rates, or to have stable rates below their norm. The chart below shows the hard work is paying off for the laggards: For reference, this is what that chart looked like three months ago when we first published it: What does all this mean for the FOMC this week? It's virtually beyond doubt that the Fed's next move will be a cut. It's a point Powell continues to reiterate. However, the importance of getting the timing right cannot be overstated. Cutting too soon or too late could impact inflation, causing it to surge, or help push the economy into outright recession. Some prominent hawkish advocates of "higher for longer" rates have recently switched sides, as data suggest high rates have done their job. Bloomberg Opinion's Mohamed El-Erian believes the Fed may be two meetings away from making a policy mistake. He argues that getting inflation down to about 3% from over 9% two years ago is good progress, and holding off rate cuts could be detrimental: The risk of causing undue damage to the economy is amplified by the stress and strain already being felt by lower-income households and small businesses. Both have seen their pandemic-era cash reserves depleted at a time when it's become far more expensive to service heavier debt loads. They can ill afford the effects of an overly restrictive Fed policy — especially when the lagged impact of higher rates is yet to be fully absorbed by the economy and the financial system as a whole.

Another Bloomberg Opinion columnist, former New York Fed chair Bill Dudley, has also switched from hawk to dove, and argues for a July cut. "Although it might already be too late to fend off a recession by cutting rates," he wrote, "dawdling now unnecessarily increases the risk."  Shoppers in San Francisco. Photographer: Bloomberg/Bloomberg Former doves have moved in the opposite direction. Absent a black swan event, SMBC Nikko's Joseph Lavorgna — formerly an economist in the administration of Donald Trump — argues that there's now no fundamental argument for a July cut; heavy fiscal outlays at a time of low unemployment combine with strong animal spirits in markets to make conditions quite easy enough without help from the Fed: The dramatic equity-led easing of financial conditions is keeping growth afloat through positive wealth creation and changing corporate and household behavior. Rising stock prices are creating enough wealth that households feel comfortable running down their savings. And rising stock prices are lifting CEO confidence enough to reduce the risk of any sizeable, economy-wide downsizing of headcount.

This is how Bloomberg's indicator of financial conditions, which combines a range of markets including stocks, captures this. Higher numbers indicate looser conditions. In the eurozone, and the US, the recent equity turbulence has had little effect, and it's hard to see any urgency for cuts: However, the markets are warming to the notion that the Fed's cutting cycle is running late. Some traders are even betting on a half-point cut in September. PGIM Fixed Income's Tom Porcelli doesn't expect this, but spells out a scenario that might justify it: It would have to be a reaction to something dramatic happening. We will get two more inflation reports and two more payroll reports between now and the September meeting. It would take a zero or near-zero print from a labor perspective over the next couple of months. Or inflation month on month, slowing to zero… I'm simply saying you would need some sort of notable deterioration in the data for the Fed to tee up a 50.

There will soon be an opportunity for such a dramatic happening. By week's end, new data for July could make the issue a lot clearer. Bloomberg Economics believes that July's ISM manufacturing survey (Thursday) and nonfarm payrolls report (Friday) will show the Fed is cutting too late: We expect the former to print in contractionary territory, while the unemployment rate will signal the Sahm Rule is close to being triggered. On average, the US economy had already been in recession for five months by the time the rule was triggered.

As the chart of rate expectations above makes clear, the Bank of Japan is an exception. Earlier this year, it took the epochal decision to move back to positive rates and to halt its yield curve control (YCC) policy of intervention to keep the 10-year yield on Japanese Government Bonds low. However, rising rate expectations in the US and the BOJ's lack of commitment to further tightening conspired to weaken the yen still further. Since the authorities' informal ceiling of Y152 was breached, successive attempts to intervene failed to stop a run on the currency — until what appears to have been latest intervention earlier this month: Helping this time is the belief that US cuts are imminent, and that Japan will remove the last vestiges of YCC by stopping intervening in JGBs. That's important because the BOJ's tightening to date has had minimal impact on the huge extra yield that's available in the US: What next? The BOJ is still buying JGBs. It will be a surprise if it doesn't announce a reduction in those purchases. More intriguingly, politicians are urging a hike. The swaps market suggests a greater chance of a hike in Japan this week than of a cut in the US. The odds of a 10 basis-point hike (the BOJ moves in smaller increments) are currently 57%: That's a lot of uncertainty surrounding a meeting due only a little more than 12 hours before we hear from the FOMC. And as the yen's opportunity to borrow at negligible rates is treated by many as a kind of warm blanket, there's a chance of big currency ructions as the US sleeps. As we said, the descent was always going to be hazardous. A guilty pleasure: It's the 71st birthday of Geddy Lee, lead singer of Canadian prog rock band Rush. Liking Rush is not something you admit in polite society, because of their politics (they dedicated an album to Ayn Rand) and because they're seen as self-indulgent, with interminable songs. They're really good musicians though. It might be self-indulgent, but try this live performance of their classic Spirit of Radio, which starts out as a cover of the Stones' "Paint It Black," or this one with such a long intro that the song doesn't even start until we're six minutes in. It's good. Happy birthday Geddy. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment