| It's hard to overstate how nervous some people in markets are about the the success of Marine Le Pen's hard-right Rassemblement National in the first round of France's legislative elections. Nothing is settled yet, and a heavy turnout meant that the RN slightly underperformed polls. Hence there was relative market calm on Monday.

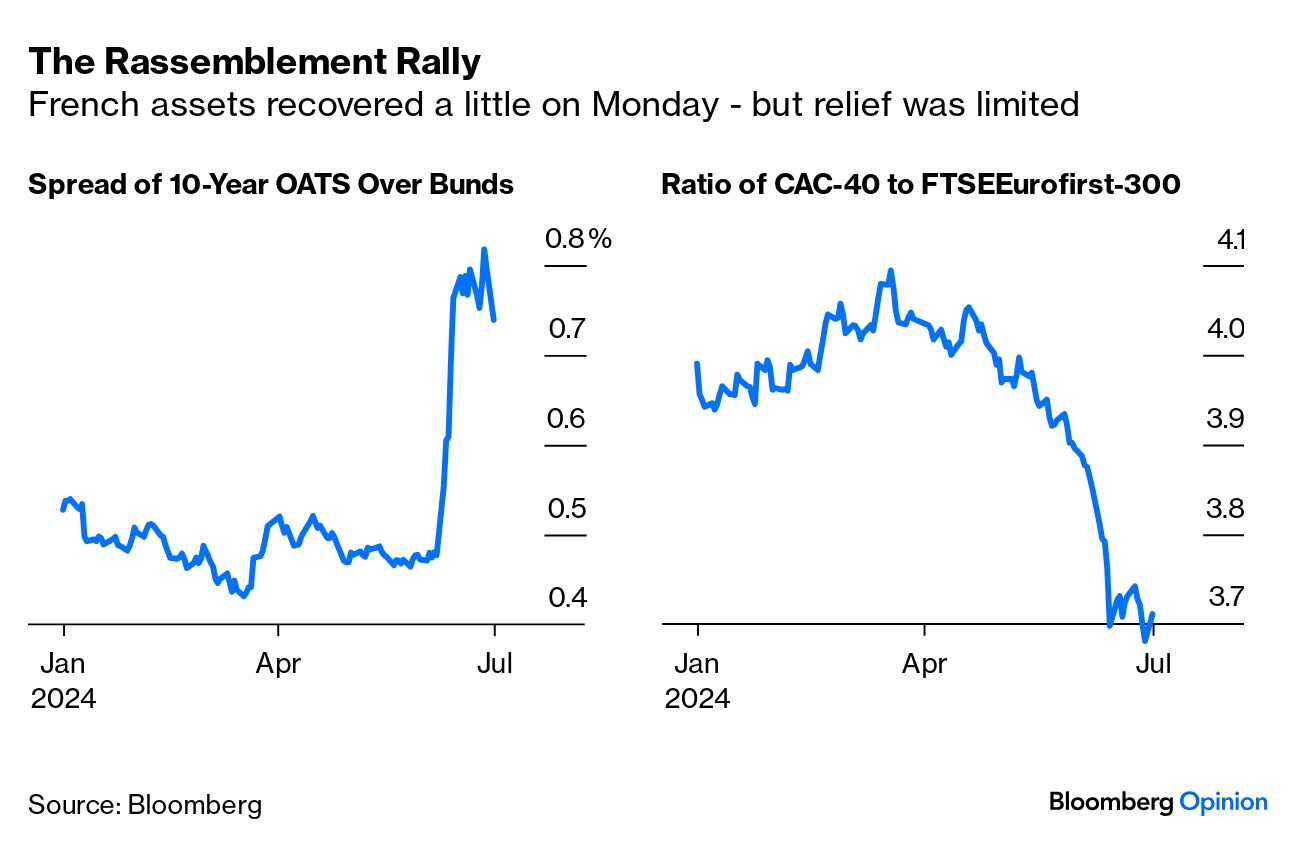

The RN's vote share shows that the so-called cordon sanitaire by centrist and left-wing parties to keep out the far right appears to have decisively broken. Generations have assumed that the far right were an influence on the French body politic but had no chance of power. That assumption is no longer safe, even if other parties somehow coalesce in the next week to thwart an RN administration. Therefore, the general uncertainty ratchets up by another level. That explains why the "relief rally" after Le Pen's showing wasn't quite as strong as polls had predicted didn't relieve much:

For now, there's a need for scenario analysis. There are two key questions. First, what kind of government is most likely to result from Sunday's second round? Second, how great is the risk of an existential crisis to the euro once it takes office? What Happens Next? The RN received 33.5% of the overall vote. First-round candidates who won more than 50% of the vote in their seat have no need to face the electorate again. Everywhere else, the second round will award the seat to whoever gets the most votes, even if short of 50%. It's not necessarily a top-two runoff; the number of contenders depends on first-round share. The key becomes how many candidates are prepared to withdraw to create two-way contests where, presumably, anti-RN forces can combine and faire barrage. Nico FitzRoy of Signum Global Advisors points out that over history, anyone who gets a third or more of the vote in the first round tends to end up forming the government, whether in coalition or outright. Also, the hurdle isn't quite as high as the 289 seats needed for an overall majority. If the RN is clearly the largest party, they'll provide the prime minister and need only pick up the support of a few friendly representatives to govern. For British parallels, think of the times that Conservatives held power with the help of Ulster Unionists, and Labour survived with the support of Scottish and Welsh Nationalists.  "Let's make a deal" is getting harder. Photographer: Nathan Laine/Bloomberg Any "Stop Le Pen" coalition is going to be unwieldy and require literally everyone else — from Trotskyists through technocrats to Greens and Gaullists — to agree on everything. That's unlikely. So while there's still much to play for, the odds heavily favor an RN government, without too many fetters. Now, what damage could they do? Could France Crash the Euro? The nightmare scenario is that France creates a crisis for the euro analogous to the sovereign debt crisis from 2010 to 2012. At that time, peripheral countries including Greece, Portugal and Ireland were unable to keep their debt within the limits set out in the Maastricht Treaty that created the eurozone. France, the argument goes, is much bigger than Greece. It's one of the two central powers of the eurozone. The rest of the EU was able to call Greece's bluff successfully in 2015, but cannot do so with France. There are already questions over French debt sustainability; if a new government were to provoke a crisis by deliberately flouting its Maastricht requirements, the euro would face disaster.  Remember Liz Truss? Photographer: Chris J. Ratcliffe/Bloomberg The biggest argument against this scenario is called Liz Truss. The gilts crisis of autumn 2022 showed that bond markets can be drastic in punishing fiscal irresponsibility. Nobody, least of all Marine Le Pen, wants to be the hapless former British prime minister, whose tenure famously was outlasted by a lettuce. The next French presidential election is due in 2027; provoking such a crisis would ensure Le Pen loses it. "The Liz Truss episode had changed European populism," says Fitzroy, adding that it allows politicians cover to blame others (the bond markets and the European Commission) for failing to make big changes. That's always handy. The next argument is Giorgia Meloni. Italy's leader since a few weeks after Truss resigned, she assumed fiscal brinkmanship was out, and has tried instead to deliver on some of her voters' priorities. You don't have to agree with Meloni (her party is descended from Mussolini's Fascists) to see that this is good politics, and it's been rewarded in the polls and markets. So we have a model for a far-right female politician taking over a major European country and nothing untoward happening, at least so far.  Meloni learned the lesson. Photographer: Alessandro Della Valle/Pool/AFP/Getty Images There's an analogy to nuclear deterrence. The fact that you can only use the weapons at the cost of disaster for yourself means that it's unlikely to happen. To quote Chris Watling of Longview Economics: If you are Meloni or Le Pen, they're thinking — either I could exit the euro or I could try to make a difference while I'm here. They're politicians. You might not agree with them but they're not stupid.

A final argument is Christine Lagarde. The European Central Bank is the ultimate underwriter of the eurozone, which it proved in decisively promising to intervene to save the euro if necessary back in 2012. She is not going too allow her country to implode. And as European banks are in much better shape than in 2010, when their heavy holdings of government debt meant a real risk of a banking meltdown, she's in a stronger position.  Lagarde won't let her own country implode. Photographer: Alex Kraus/Bloomberg Just possibly the European model is beginning to work the way it says on the label, even if much more slowly and inefficiently than intended. Having had its crisis, the rules of the eurozone are clearer now. Try to break the spending limits, and the bond market will punish you by sending your borrowing costs skyward. The ECB will only save you if you agree to austerity. Individual countries gave up some of their freedom over their budgets when they joined the euro. There's no longer any point playing brinkmanship, because we know how it ends. That doesn't mean all will be smooth. Another analogy is with the infuriating annual ritual of the negotiations over the US federal debt ceiling. After huffing and puffing, there is always an agreement to kick the can down the road a little further. But everyone has to go through the whole pantomime, and it's a dreadful way to set policy. Deficits don't come down, and taxpayers' money isn't well-directed. That kind of scenario looks depressingly likely. Disaster may be avoided, but it does lead to US-style deficits and could well guide France and Europe into further underperformance. Even before Japanese officials propped up the struggling yen with over $62 billion in April, it was obvious relief would be fleeting. The subsequent descent to the currency's lowest level in nearly four decades is a horrific showing that few saw coming. Nevertheless, to say the intervention was money down the drain is a stretch. If anything, investors know that the yen's troubles are partly fueled by factors outside of Japanese control — higher interest rates in the US. At best, the Ministry of Finance's intervention bought some time, and the opportunity cost of not doing so might have been disastrous. Two months ago, the yen traded near 158 to the dollar, viewed then as the line in the sand. Now near 161, the main question is not about whether an intervention is imminent. It's how frequent interventions can be. These are costly decisions Japanese officials cannot take lightly. In the last few days, officials' constant warnings of defending the yen fueled speculation about a new line in the sand. It's essential to understand the cause of the depreciation and how close authorities are to stepping in. Bank of America's Shusuke Yamada views 165 as the new ceiling that could trigger an intervention: We maintain our view that the structural yen weakness drives policy response, which in turn impacts broader yen markets. While FX intervention can slow the yen's decline and could cap USD/JPY below 165 for the time being, it is unlikely to change the fundamentals and structural capital outflows.

There's no belaboring the point that the yen is susceptible to actions elsewhere. Authorities' options are limited. Citigroup estimates that Japan has $200 billion to $300 billion of ammunition to fund any further intervention campaign. However, Bloomberg Economics' Taro Kimura argues it's not all gloomy and that the yen is more likely to strengthen than to weaken in coming months "as yield differentials turn more favorable." For all its troubles, a weaker yen has been a boon elsewhere, especially to exporters, although concerns over import costs and consumer sentiment easily negate that. Japan's Topix has been surging to its highest levels since 1990. It could be spurred further if inflation expectations fueled by a weaker yen lead to a rate hike. The following chart shows how close the Topix has come to eclipsing its 34-year-old record: The belief that the Topix can set a new record is gaining ground. To start with, fund managers expect banks to benefit from the policy rate shift, with a BofA Asia fund manager survey showing that global investors are most overweight the sector in Japan. Still, any outperformance will likely be measured. As Gavekal Research's Yanmei Xie and Udith Sikand note, having come close to its 34-year high, the broad Japanese equity market is no longer a steal. —Richard Abbey  Alan Ruskin has some career advice. Photographer: Christopher Goodney/Bloomberg I'd like to share some advice from one of finance's great survivors. Alan Ruskin, a hugely respected foreign exchange analyst who most recently plied his trade for Deutsche Bank AG, retired last year after 42 years in finance. I was a regular reader of his notes for the latter half of that, and I will miss them greatly. To sign off, he offered some conclusions and advice. Highlights include: - Never underestimate LUCK, most especially early in a career.

- Of his first job as an online researcher: "It was Maggie Thatcher's days of 11%+ unemployment, and I would have paid to take this kind of online research job. And I just about did. The starting salary was 6,000 sterling per annum. Early on, experience is worth so much more than money."

- After launching a start-up successfully, he went trekking in the Himalaya: "Six months into my travels, two of our best analysts were poached. My colleagues went searching for me to come back and help out, but I was trekking and nobody knew where I was... for months. A few lessons here. Go trekking. It's not 1990, throw away your cell phone."

- While satisfying his wanderlust, he learned a lot about the development of India, China, and Russia in the declining days of Gorbachev (while reading War and Peace). The time off "made it easier to settle down, have kids, and I am sure added to my career's enjoyment and longevity. There is so much to be said for sabbaticals. They can be a huge win for employers as well as employees."

Don't be in too much of a hurry, everyone, and best of luck with what comes next to Mr. Ruskin. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment