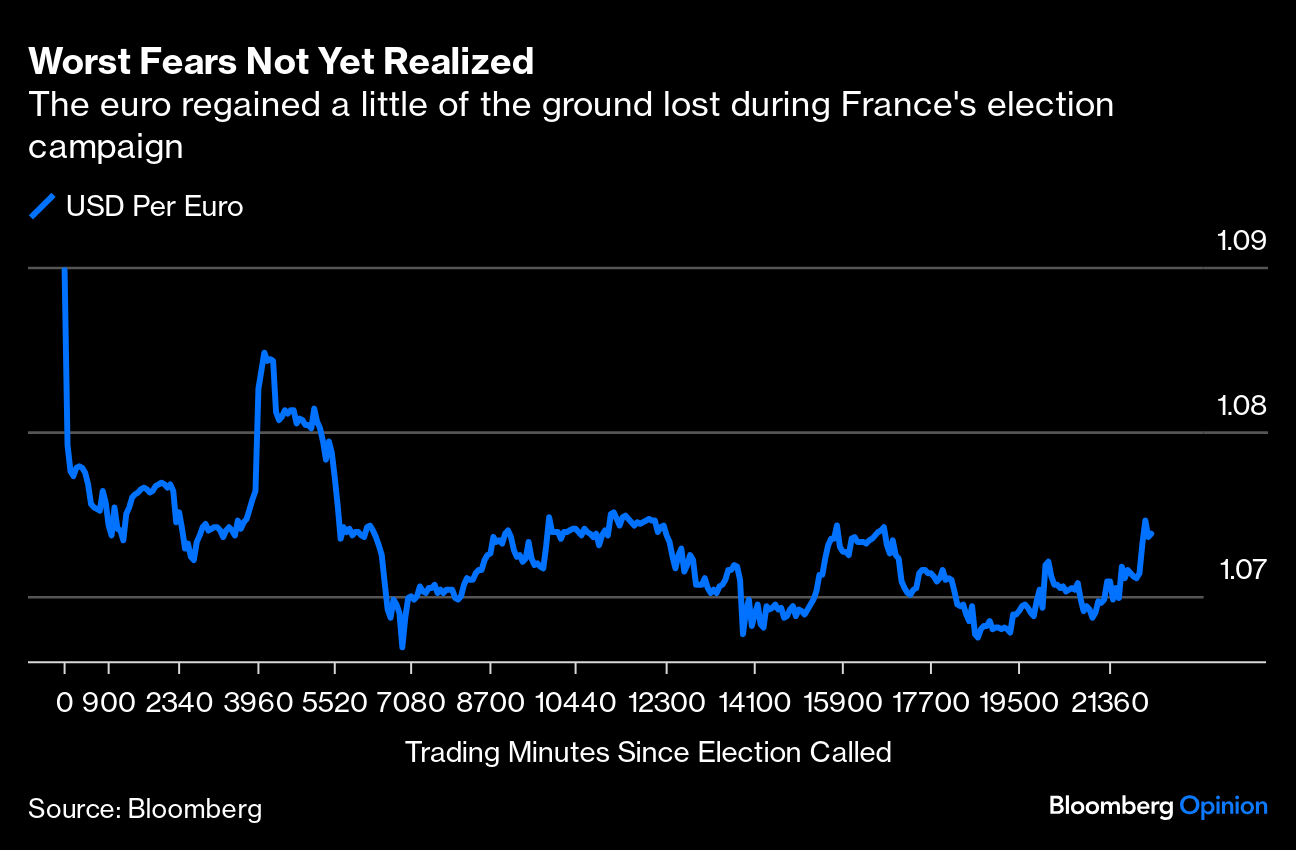

| The first-round verdict of France's legislative elections is clear, up to a point. The hard right and hard left have beaten President Emmanuel Macron's party into third place, and provisional projections suggest that the National Rally has a chance of an overall majority after next Sunday's second round (though the range of possible seats for each is wide). That doesn't sound good for investors. However, the Rally, led by Marine Le Pen, appears to have done slightly worse than expected, and there's a chance of gridlock, or of an alliance between Macron and the forces to his left against her. None of these options is appealing and political uncertainty remains. But the very worst fears have not — yet — come true, and so the euro has actually gained a little in Asian trading.  The market has thus done a pretty good job to date of pricing in the risks that Macron's gamble has created. Stepping back, there's little reason to be happy, particularly given the French penchant to take to the streets. Tina Fordham of Fordham Global Foresight suggests: The fact that the far right in France has broken through the "cordon sanitaire" is not only concerning on various levels, but it is likely to trigger civil unrest. Without justifying the enormous gamble that Macron has taken, it bears remembering that strong performance by extreme parties in the first round of French elections is not unusual.

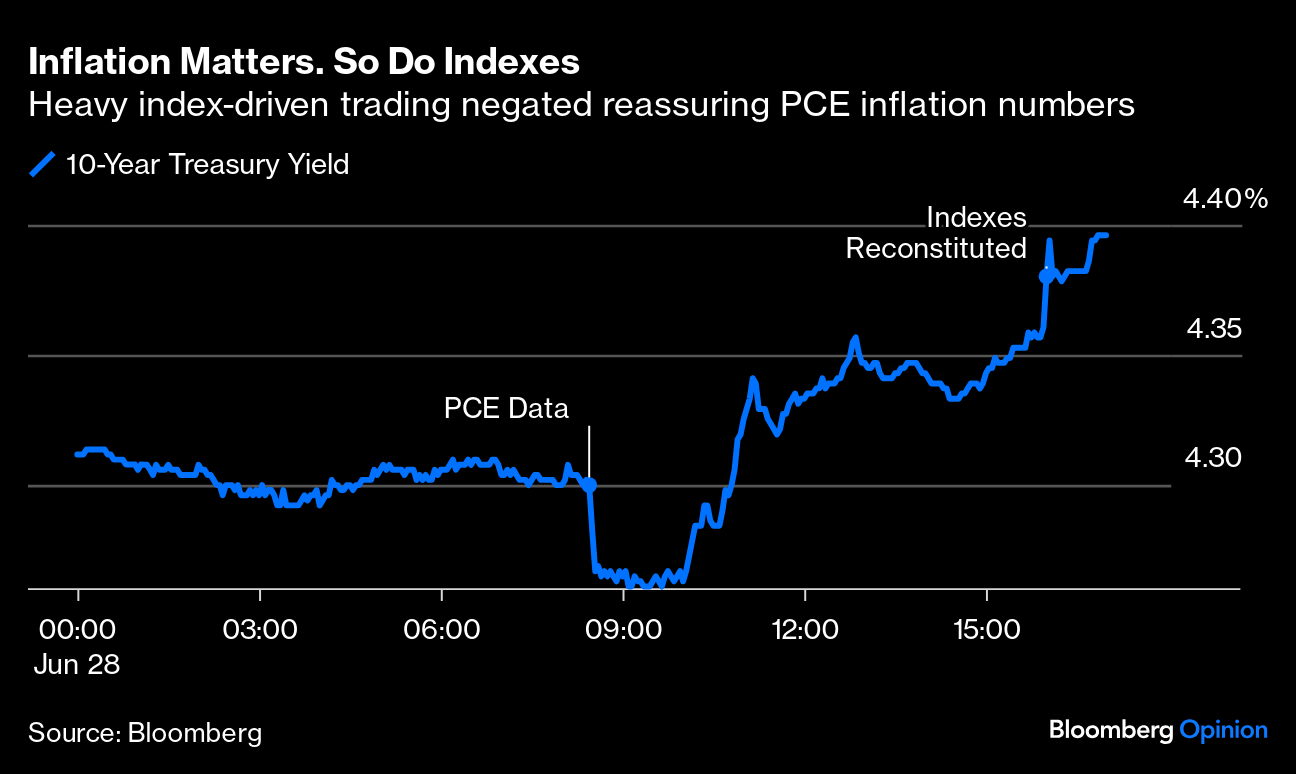

She adds that the decisive second round July 7 could have profound implications for eurozone stability, Ukraine policy and more. It's also not at all clear that the center and left will be able to coordinate. They have until the end of Tuesday to agree to withdraw candidates from different constituencies. Where alliances cannot be thrashed out, contests become what the French call "triangulaires," with the winner possibly not gaining 50%. Nico FitzRoy of Signum Global Advisors suggests that the number of three-way races looks set to "far exceed even the biggest pre-election estimates (IPSOS, here, now expects 285-315 triangulaires instead of 120-170)." That would make the result that much harder to call and set up potential surprises.  Left-wing protests at the Place de la République in Paris. Photographer: Nathan Laine/Bloomberg Meanwhile, in four days, UK voters are expected to boot the incumbent Conservatives in a landslide. And across the Atlantic, there's seething speculation that President Joe Biden may somehow be forced to stand down after an embarrassingly bad performance in the first debate — although at the time of writing he seems to be resisting the calls to quit. All of these things matter greatly. Politics will remain a hostage to fortune throughout the week, and clarity a moving target. Meanwhile, a big question remains… With the first half of the year now over, the MSCI All-World index is up 10.3%. Nothing wrong with that. True, there's a big imbalance between the US (up 14.8%) and the rest of the world (4%), but this still is far stronger than we would expect if markets were seriously alarmed. The strength can ultimately be attributed to two factors: Disinflation The single biggest reason for this strength, the hidden necessary condition, is an assumption that inflation is beaten. Concerns over how long it will take to get year-on-year price rises down to 2%, or to restore living standards for poorer people worst hit by the price spike of 2022, aren't really so relevant. The important point is that inflation won't go back up, so rates won't need to rise. If that's right, all things become possible. And the latest Personal Consumption Expenditure deflator figures for May, published Friday, confirm that the Federal Reserve's favored inflation gauge is steadily declining. Both the core PCE — excluding particularly variable items — and the trimmed mean produced by the Dallas Fed, which excludes outliers and takes the average of the rest, are now below 3%. They remain above target, but the direction of travel seems clear:  rt There's room for much argument about exactly how fast the Fed can cut rates from here, but very little case for a hike. That's what matters. If rates are reducing, then it's safe to buy risk assets now, and that's what asset allocators are doing. The latest quarterly survey of allocators by Absolute Strategy Research shows this clearly. Confidence that the PCE will be lower still a year from now remains very strong: That translates into strong confidence that the era of monetary tightening is over. It's possible that rates will remain on a plateau for a while, but there's confidence that policy will ease from here, and not tighten: What's strange about this is that the confidence is not broadly shared. Last week saw the latest updates of surveys of inflation expectations conducted by the Cleveland Fed among company managers and the University of Michigan among consumers. Over the next 12 months, consumers think inflation will continue at roughly the level it is now. Companies are bracing for an increase. If inflation really is at nearly 4% this time next year, as companies predict, rate hikes will be back on the agenda: The consumer survey conceals a growing split over how bad future price rises could be. The most commonly cited figure is the median, but Michigan also publishes a mean, which is generally higher (very, very few people expect negative inflation, after all). The way the mean and median have parted company over the last year is spectacular. This chart shows the mean and median consumer expectations for inflation over the next five years:  If the average American consumer expects inflation to run at more than 5% for the next five years, that implies that expectations have veered out of control. With the median below 3%, a significant body of people must be braced for double-figure price rises. That's incompatible with policy easing, and would throw a wrench into more or less any positive scenario for the economy. It's possible that a coterie of ideological conservatives have convinced themselves that hyperinflation lies ahead, but even then it's bizarre that their forecasts are higher now than two years ago when inflation was at its peak. These expectations matter because they can be self-fulfilling. If companies and a significant chunk of the population are bracing for higher prices ahead, that will affect their behavior. And if they're right, many of the world's most important asset allocators are wrong. Earnings and AI The other vital factor keeping markets so buoyant is earnings. Corporate profitability appears to be fine, and there's little fear among asset allocators that profits will come down in the next year. This is from the Absolute Strategy survey: What's strange is that this seems almost divorced from the economic cycle, where views are more diverse. It also flies in the face of profit margins' long-established historical tendency to revert to the mean. That's chiefly because of artificial intelligence. "The fervor around AI has really distorted historical relationships," said David Bowers, who conducted the survey for Absolute Strategy. "People are saying things like, 'I'm a strategist not an AI expert. I don't want to fight this one.'" In other words, the bet is on that AI has raised the profit share, or the proportion of revenues that companies can keep as profit, a number that tends to mean-revert, and has underwritten a continuing secular rise in earnings growth. That's a big assumption. For the time being, tech companies are taking an ever greater share of the market and their earnings look impregnable, perhaps because they're operating in oligopolistic conditions. The biggest risks to look out for, then, are an emphatic rise in inflation, or a major reverse for AI. Both would set the cat among the pigeons. As for politics, asset allocators aren't so bothered. So economically consequential political surprises could indeed matter a lot. On which note... It's worth a quick look at the extraordinary presidential debate in the US and its market aftermath. President Biden did terribly, as Timothy L. O'Brien explains. The perception of his chances in betting markets, compared to Donald Trump's, was extraordinary. This is the gap as measured by Real Clear Politics' survey of betting odds: It's very rare for a single political event to have quite this effect, but the reaction seems justified. A second Trump term now looks far more likely, and the best chance of averting it may require a period of turmoil as Democrats try to settle on an alternative candidate (who won't have benefitted from the brutal vetting process of a primary campaign). These are hugely consequential matters. But it's hard to see any impact on markets. This is what happened to the 10-year Treasury yield on Friday:  Initial reaction was minimal. The PCE data, as might be expected, allowed the yield to drop sharply. And then the bond market went through a big swing, rising by 15 basis points from there until the close. It's possible to construct a political narrative for this. Trump 2.0 involves unfunded tax cuts and sweeping tariffs, which would be bad for inflation and increase government borrowing needs, implying higher yields. But if the market is running scared of Trump, it would have shown that much earlier in the day. Rather, it might be more significant that Friday was the last day of the first half, which is when indexes are reconstituted. This reliably leads to heavy trading as investors aim to get into stocks and bonds that will enter indexes, and get out of those that leave. That caused bond yields to surge, and also drove a stock selloff in the Wall Street afternoon. FTSE Russell, which controls the Russell range of indexes that are all rebalanced annually at midyear, announced that trading volume was the highest yet on reconstitution day, with $219.6 billion traded across Nasdaq and NYSE. Politics matters. But so do indexes. And they appear ever more to be leading rather than just following the markets they track. This is being written from England, where the European football championships are creating very much more excitement than an election nobody seems to care about. England were frankly dreadful against Slovakia, but won thanks to an extraordinary overhead kick by Jude Bellingham five minutes after normal time had expired. I have great difficulty understanding how anyone can execute a so-called bicycle kick successfully, and the risk of breaking your neck seems extreme. But wow, they're great to watch. Some other great bicycle kicks came from Marco Van Basten, Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Wayne Rooney, Sassa for the Rio club Botafogo (I was there for that one), Alireza Jahanbaksh (that one too; it was scored for Brighton against Chelsea), and Alejandro Garnacho. What fun, and I wish I could do that. Have a good week everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment