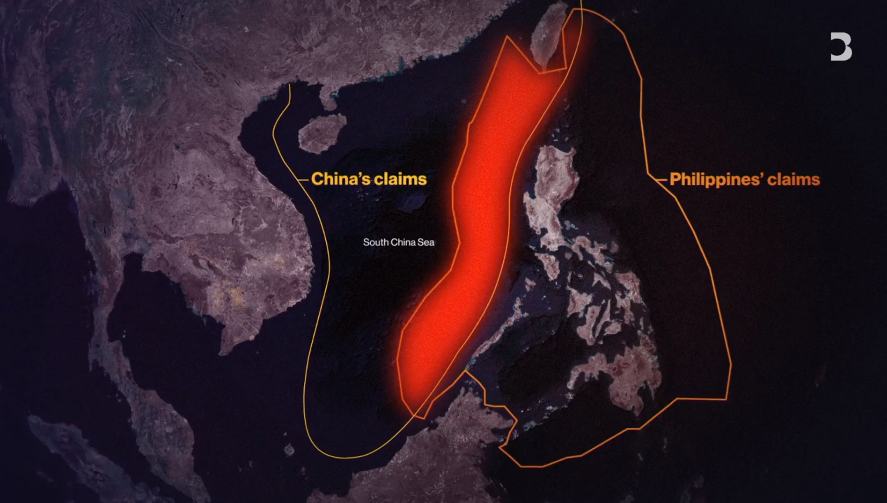

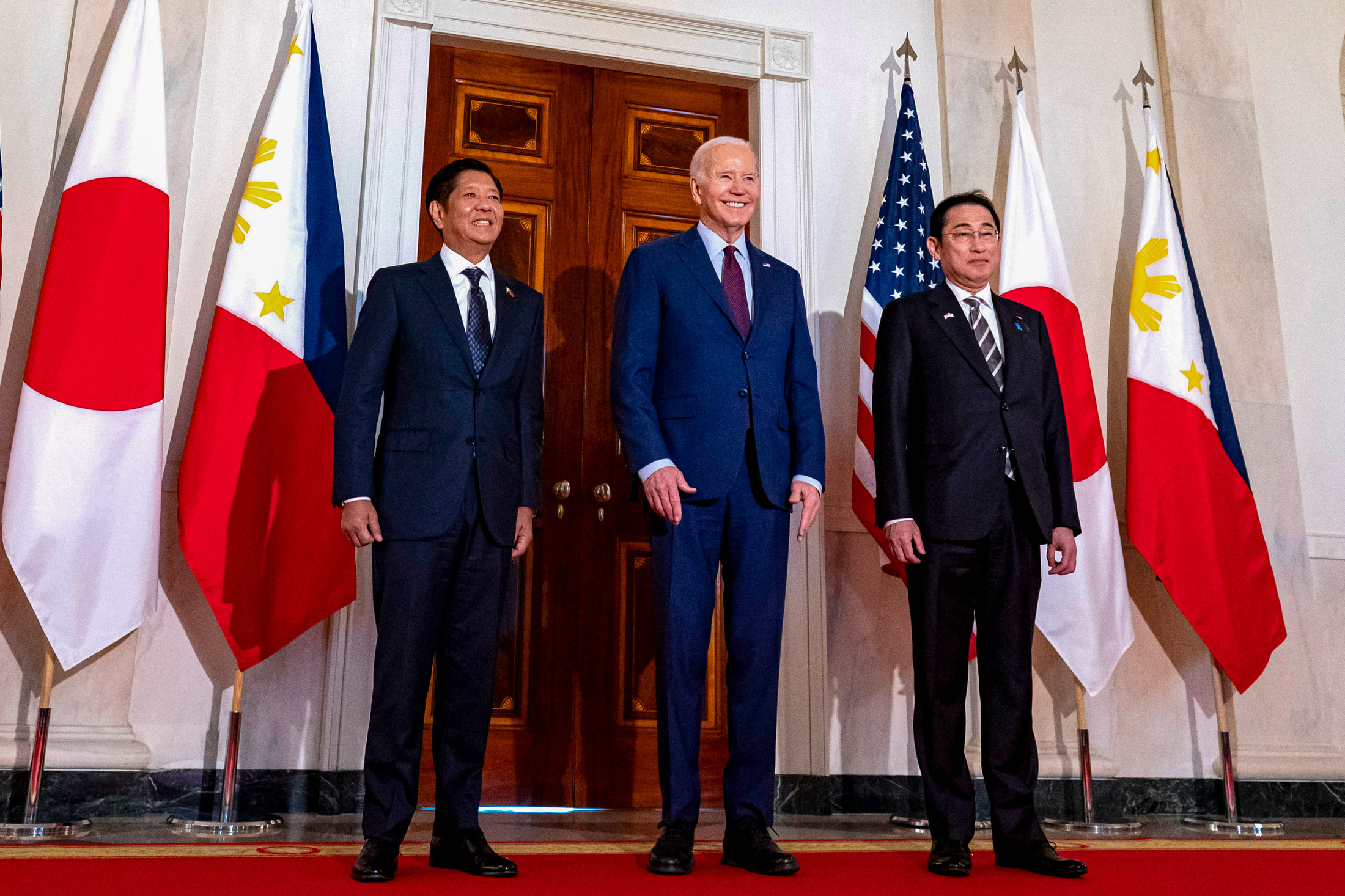

| The 1982 state visit of the Philippines president to the White House would seem like an obscure footnote in diplomatic history. But since the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library posted a video of Ferdinand Marcos's speech on the South Lawn seven years ago, it's racked up over 8 million views. Fervent comments on the video showcase the enduring hold on Philippine attention that the late dictator Marcos has—reinforced by the fact his son, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., is now president. The substance of the 1982 speech also speaks to the strong bilateral relationship the two countries then had, with thousands of American troops stationed in what were thought to be permanent bases in a vitally strategic Western Pacific location. Subsequent decades showed the folly of taking the relationship for granted: in the 1990s, the Philippine Senate voted to expel the US from those key bases, and in more recent years, under former President Rodrigo Duterte, Manila tilted strongly towards Beijing over Washington. Under Marcos Jr., the pendulum has swung back decisively—despite the US having helped facilitate the ouster of his father. He's even invited the American military back to a string of different bases. The big question is how long this phase lasts. The answer rests on economics, and whether Washington is able to mobilize large-scale US investment in its one-time colony, providing tangible benefits to Philippine voters.  Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Photographer: Veejay Villafranca/Bloomberg Oddly though, the Biden administration hasn't emphasized the Philippines in its "friend-shoring" push to build up supply chains that don't include China. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, the most visible proponent of the initiative, often mentions India and Vietnam, and has been to both. But not the Philippines. That's despite the two nations' long-standing ties, a large Philippine labor force (a good share of which is English speaking) and democratic credentials that distinguish it from Communist-ruled Vietnam. Economists highlight two major concerns with the country, however: bureaucracy and energy supply, with power costs that are among the highest in the region. The Malampaya gas field supplies a fifth of the power for the country's main island, Luzon, and it's forecast to become commercially depleted by 2027. Some estimates show that could happen even sooner. All the more reason for the US and its partners to step up economic assistance. Philippine Ambassador to the US Jose Manuel Romualdez, a cousin of the president, said in an interview this spring that his country is indeed counting on its friends to help tap energy resources in the South China Sea.  Disputed waters in the South China Sea Source: Bloomberg The rub, of course, is that those maritime stretches are in dispute. China claims almost the entirety of that body of water. Chinese and Philippine vessels are in regular stand-offs these days, with US—a treaty ally obligated to defend the Philippines—typically keeping watch from the skies. "The lifegiving waters of the West Philippine Sea flow in the blood of every Filipino," Marcos dramatically said in a keynote speech at a security forum in Singapore Friday. And indeed, the body of water is estimated to hold significant quantities of oil and gas, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The key will be whether the US and its democratic, industrialized partners (especially Japan) will follow through on helping to develop the resources. Economic cooperation has been evident in other areas: in April, President Joe Biden hosted an inaugural trilateral summit with Marcos and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, where the three nations mapped out the "Luzon Economic Corridor," a planned showcase endeavor. Last year, the Philippines dropped China from funding options for three key railway projects, and now envisions the US and Japan for a new freight line.  Ferdinand Marcos Jr., left, Joe Biden, center, and Fumio Kishida, right, on April 11 Photographer: Al Drago/Bloomberg The US is also planning deals on semiconductors and nickel processing projects. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo led a US delegation to the Philippines that included about 20 American executives, obtaining accumulated pledges of more than $1 billion in investment. But much more than that will be needed to meet Marcos's vision of the Philippines becoming Asia's next manufacturing and logistics hub. Above all, it will come down to energy supplies. "The bottom line is economic prosperity—if we do not have economic security, we can have all these defense agreements and it would mean nothing to us," Romualdez, the nation's ambassador to Washington, said. It's not entirely clear whether Washington will deliver, all the more so if a newly convicted Donald Trump, who placed scant value on alliances in his first term, nevertheless wins the November election. But there's a bedrock of US-Philippine history to build on, and new history to be made. —Chris Anstey Get the Bloomberg Evening Briefing: Sign up here to receive Bloomberg's flagship briefing in your mailbox daily—along with our Weekend Reading edition on Saturdays. The Big Take Asia podcast: Each week, Bloomberg's Oanh Ha reports on critical stories at the heart of the world's most dynamic economies, delivering insight into the markets, tycoons and businesses driving growth across the region and around the world. Listen in here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment