- History is clear; it's very, very dangerous to get out of stocks altogether;

- Buy Now, Pay Later is a big deal, to which Bloomberg has devoted a Big Take;

- It's helped the most vulnerable — but it might be distorting consumption data;

- AND Stormy Daniels can never match the courtroom drama of Marisa Tomei

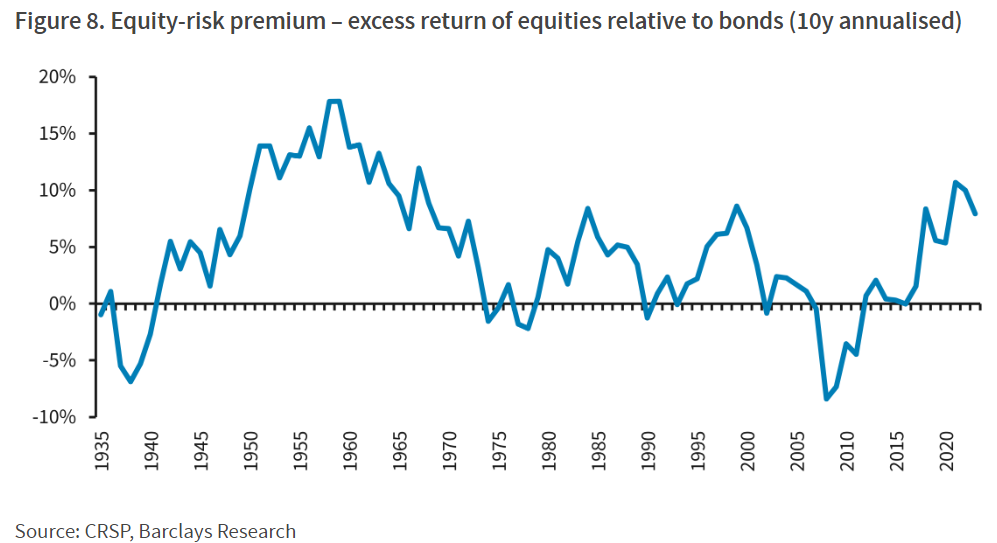

Points of Return often argues for caution on stocks. It never argues to get out of them altogether. That's because history demonstrates that over long time spans it's very dangerous to be out of the market altogether. With the recent publication of this year's edition of Barclays PLC's long-running Equity Gilt Study, which started as a running comparison of the returns on UK stocks, bonds and cash over the very long term, there is more evidence. This is possibly the most important "money chart," showing the total range of returns for different asset classes in the US since the Barclays data starts in 1925. Over short periods, it confirms that equities can inflict really serious losses; the greatest on record have been worse than for bonds and equities. But the longer term is your friend. Over no 20-year period since 1925, a span that includes both the stock market crash of 1929 and the global financial crisis of 2008, have equities failed to beat inflation. That cannot be said of any other asset class: And to look at the magical effects of compound interest, this is what would have happened to investments in cash, bonds and equities for someone who invested in 1925 and then held it (presumably passing it on to descendants somewhere along the way): The same pattern is confirmed in Barclays' home market of the UK, for which its data stretches back to 1899. The last 125 years have been much less kind to Britain's economy and financial markets than they have been to the US, and so there was one 20-year period over which stocks lagged inflation. Once Barclays expanded to 23-year periods, however, stocks again were a failsafe guard against inflation. As in the US, the compounding effect works for equities in the very long term. This is how a £100 investment in 1899 would have accumulated over the last 125 years: The bottom lines from this meticulous research are that it is really risky to get out of the equity market altogether. Unless you absolutely know that you will need to spend your entire nest egg some time next year, you should always have some money in stocks. This is more true the more patient you can afford to be. The arguments in Stocks for the Long Run, the investment classic published in 1994 by finance professor Jeremy Siegel at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, remain valid. This is sometimes caricatured to mean that investors should be 100% invested in stocks all the time. The numbers for 1- and 5-year returns show that that would be unwise. If there's any risk that you might need money in a hurry, then you need to keep some money in cash and bonds. And beyond that, to quote the father of modern portfolio theory Harry Markowitz, "diversification is the only free lunch in investing." In mathematical terms, it's hard to argue against this as some degree of diversification will improve risk-adjusted returns from stocks, although in behavioral terms it's questionable. Far from feeling like a free lunch, holding stocks during a big sell-off, or keeping some money in cash while the stock market surges, can be extremely difficult to swallow. After that, asset allocation descends into abstruse arguments about whether it makes sense to shift between asset classes, whether it's possible to time those shifts, and whether we can really tell when one asset class is cheaper than another. Barclays publishes a classic measure that aims to gauge this, the equity risk premium — defined by them as the gap between 10-year rolling returns on stocks and bonds. The higher the premium, the more you are banking on equities to outperform in future.  As the Barclays team points out, the equity risk premium is falling from a 2021 high (set during the stimulus-driven excitement in the year after the pandemic broke) where it reached its highest in more than 50 years. (The very high premiums of the 1950s reflect the financial repression with which the government intervened to keep bond yields lower and thereby make it easier to pay off war debts.) However, it's uncomfortably high, and close to its peak in 2000 when the dot-com bubble burst. So history suggests this isn't the greatest time to take a big overweight position in the stock market. But it also emphatically suggests that you should stay invested to some extent at all times. Flights. Concert tickets. Groceries. Fashion accessories. The list of what consumers will seek to purchase using "buy now, pay later" services is endless. Why pay in full when there is the option to spread the payment (or pain), over time, typically at zero interest? For BNPL proponents, it's a wonderfully convenient way of funding their spending beyond what their finances can immediately accommodate, and doing so without sinking into financial distress. Consumers' nearly insatiable demand for short-term and unsecured credit drives the global BNPL industry, which is on course to reach about $700 billion in transactions by 2028. Total global consumption expenditure is about $72.5 trillion, according to the World Bank, so this would still be less than 1% of the whole. Retailers offering BNPL accept payment in installments for the purchase of a specific product with a down payment due at the sale and a fixed repayment schedule. Usually, consumers pay little to no fees and zero interest on the purchases, while their indebtedness has little impact on their credit scores. If this sounds too good to be true, what's in it for these companies? They charge merchants fees of around 5%-8%, way above the 2%-3% typically charged by credit card companies. But what happens if consumers run out of money? Lurking behind the convenience is a monster waiting to happen when the consumer defaults, as detailed in this piece for Bloomberg's Big Take. BNPL's popularity has surged so quickly that regulators are still playing catch-up and often bundle BNPL together with credit cards. That's discomfiting for anyone trying to get a handle on critical issues of consumer confidence or the risk of individual bankruptcies. As Wells Fargo & Co. Senior Economist Tim Quinlan told our Bloomberg colleagues, he is spooked by the "phantom debt" that he can't see. However, regulators do know that they have plenty of work ahead of them to get a hang of the situation. The US consumer-driven economy has defied the inflation spike that spurred the Fed to raise interest rates. The latest reading for retail sales excluding food and autos showed a 4.2% increase in the year to the end of March — its fastest growth in more than a year. That is a puzzle, and many assume that is only a matter of time before consumers can no longer bear the weight of the price surge. Looking for signs of distress is a data-dependent endeavor, and it makes most sense for now to zero in on the most vulnerable consumers, who would logically buckle first under high interest rates. Is BNPL keeping these people afloat? As noted in this National Bureau of Economic Research paper, lower-income users are more likely to use BNPL relative to credit cards, which isn't surprising — it's a logical preference for folks with less access to liquid resources. A recent Bank of America analysis of the share of its own customers adopting BNPL showed a year-on-year slowdown. That provides some evidence to back up signs of cooling that might not show up yet in the official macro data. This Bank of America Corp. chart highlights the slowdown but also shows a fall in BNPL use among people with higher incomes: That tends to back the NBER's paper, which stated that the higher-income earners tend to put larger-ticket items on BNPL. What's disconcerting is BofA's finding that heavy users of BNPL have also been racking up more credit card debt: Perhaps more significantly, while internal Bank of America data shows that average credit card balances have increased from 2021 through March 2024, they've been rising faster for medium- and heavy-use BNPL households since mid-2021. So, there appears to be some evidence that BNPL users, particularly heavy users, may have a less robust financial position than the average household.

It's tempting to suggest, therefore, that BNPL has indeed acted to mask a growing credit problem, of the kind that would be expected when monetary policy has tightened so sharply. The companies at the forefront of BNPL services, however, are marching on. Major retailers like Walmart Inc. are in the fray to partner with BNPL companies, opening up the services to their customers. Financial Insyghts' Peter Atwater argues that these companies, which have their roots in subprime lending, only arrive near the very end of a credit cycle when lenders and borrowers both feel most confident. But a slowdown could spell more distress: I think that we're seeing increasing levels of distress among lower-credit-quality borrowers. And I think that we are seeing that now being reflected not only in the prices of companies like Affirm but also in their general willingness to lend. You're seeing more conservative lending because of the rising delinquency rates.

Atwater suggests that the share price of San Francisco-based Affirm Holdings Inc., a financial technology company that is probably the best known BNPL provider, can be taken as a canary in the coal mine. It's had a wild ride since going public early in 2021, and at one point had a market capitalization of $45 billion, which was remarkable. For comparison, the current market cap of Bank of New York Mellon, one of the most famous banks in the nation, is about $42 billion. Affirm is now, however, worth just under $10 billion: The company still trades at 3.7 times its book value, far ahead of the KBW index of large commercial banks which currently trades at 1.2 times book, so there is no way that Affirm is being treated as a distressed institution. Rather than showing alarm about the company, the market is demonstrating that it still isn't sure that it understands it. It's best to resist the temptation to generalize the signs of distress emerging from the sector. The data currently available is just a fragment of a larger consumer market. Globally, BNPL forms about 4.2% of e-commerce transactions, and the chances are that regulators will steadily exert more control over it. It's possible it's distorting data that suggest the consumer is surprisingly strong; but its role in providing a lifeline to the most vulnerable cannot be ignored. -- Reporting by Richard Abbey Thursday will see the resumption of Stormy Daniels' cross-examination at the ongoing criminal trial in Manhattan of former President Donald Trump. I am not going to offer a link to any of her oeuvre. However, all the reports suggest that her testimony on Tuesday offered compelling courtroom drama, with more to come. Whatever your opinion of the politics, it's quite a show. So, to get you in the mood, try some famous courtroom scenes from A Few Good Men; To Kill a Mockingbird;12 Angry Men; My Cousin Vinny; and Pink Floyd: The Wall. Any more out there? More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment