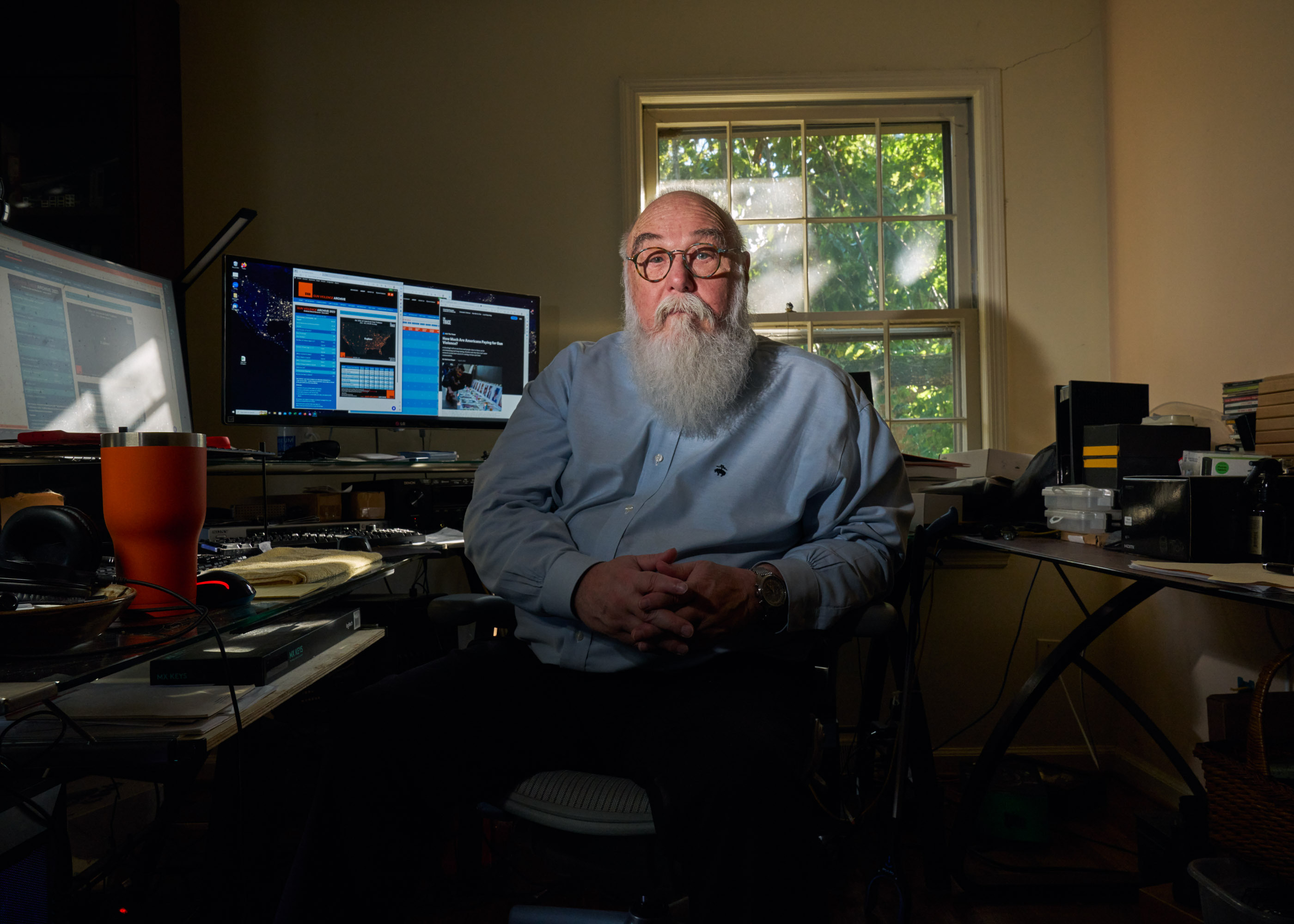

| Welcome to Bw Daily, the Bloomberg Businessweek newsletter, where we'll bring you interesting voices, great reporting and the magazine's usual charm every weekday. Let us know what you think by emailing our editor here. If this has been forwarded to you, click here to sign up. Dan Kois was a new editor at the online publication Slate when the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, happened in late 2012. Twenty of the victims were 6- and 7-year-olds. Kois, who has a child who was then about the same age, says, "It really freaked me out." A data journalist by trade, he went looking for numbers about gun violence in the US but "kept running into a bunch of brick walls, different numbers in different states, and different numbers that seemed shockingly old and out of date." Tens of thousands of shootings take place every year in the US. Some, such as the one on Oct. 25 in Lewiston, Maine, get a lot of attention because of high casualty and injury figures and an ensuing manhunt; others, like the one the next day that left five people dead in Clinton, North Carolina, don't. And yet regardless of how sensational the episodes are, no one federal agency keeps track of them. Data is siloed, which makes it difficult to study a public-health crisis that kills more kids annually than cancer, drug overdoses or car accidents. This lack of transparency isn't unintentional. The National Rifle Association successfully lobbied lawmakers to pass a provision in annual appropriations legislation that for years prevented US health agencies from collecting data on shootings. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, doesn't have a guaranteed earmark from Congress to study gun violence in the same way it does other causes of death; in 2021 the agency got $25 million for this purpose, but it has to split that money with the National Institutes of Health. What information the CDC does gather can take six months or longer to analyze. Its data collection systems aren't equipped to track injuries. For its part, the Federal Bureau of Investigation collects data on firearms used in murders, robberies and aggravated assaults. It moved recently to a new crime-tracking system that allows for more granular data than the one it used previously, but so far police departments have been slow to transition. One-third submitted no crime data of any kind in 2021. To "resume providing nationally representative data" in 2022, the FBI said it would accept summary reports from departments that haven't transitioned. And there have long been NRA-backed policies restricting how the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives can store and publicly release data, too. Kois thought that by crowdsourcing information about shootings, his Slate team could come up with a more accurate real-time picture of US gun violence. They began by asking social media users to flag shootings that they came across, and emails started to pour in from people looking to help. A guy in Lexington, Kentucky, named Mark Bryant was particularly engaged. Before retiring in his early 50s, Bryant had worked for companies such as Microsoft Corp. and International Business Machines Corp., where he was a computer systems architect. In late 2011, a 36-inch-long blood clot that could have put him at risk for more serious issues such as pulmonary embolism or stroke landed him in intensive care. When he got out of the hospital, he says, he felt like he was given a second chance. "I have one more good gig left in me," he thought. "It's gotta be good, and it's gotta be right." Eight months later there was a mass shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. Horrified by what happened, and annoyed generally at the politics around the issue, he went online for answers—and was still looking when Sandy Hook happened.  Bryant. Photographer: Stacy Kranitz for Bloomberg Businessweek How many kids die annually from gunshot wounds? Bryant wanted to know. In the wake of Sandy Hook, NRA Chief Executive Officer Wayne LaPierre had introduced the (now oft-repeated) phrase that "the only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun." How often did that happen? The answers weren't easy to find. Eventually Bryant came across Slate's project and started comparing his research with theirs. He noticed discrepancies. "Hey, you missed one," he emailed the team. Bryant and the editors at Slate went back and forth until, inevitably, it made sense that they join forces. A year after Newtown, Bryant and the team had tallied more than 11,400 deaths. But that number was a drastic undercount. Slate's researchers lacked the time and resources to be more comprehensive and, eventually, to keep the project going. But Bryant wouldn't give it up. Today, what was rebranded as the Gun Violence Archive is the US's sole repository of near-real-time data on shootings. Incidents can be sorted by deaths or injuries, the age of victims, a shooter's intent, mass shootings or geographic location. That's made it the go-to source on shootings for the media, academics and politicians. Tracking, logging and verifying every shooting in the US is daunting. It requires an obsessive attention to detail, a knack for statistics and a willingness to drop everything at a moment's notice whenever there's a mass shooting. The GVA defines one as having a minimum of four victims shot—either injured or killed—not including a shooter, and there were 619 this year as of Nov. 27, by its count. No one's been more obsessive than Bryant has in compiling all that trauma. It's taking a physical and mental toll. For more on how this citizen effort at data affects Bryant and his team, read the whole moving story by Madison Muller here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment