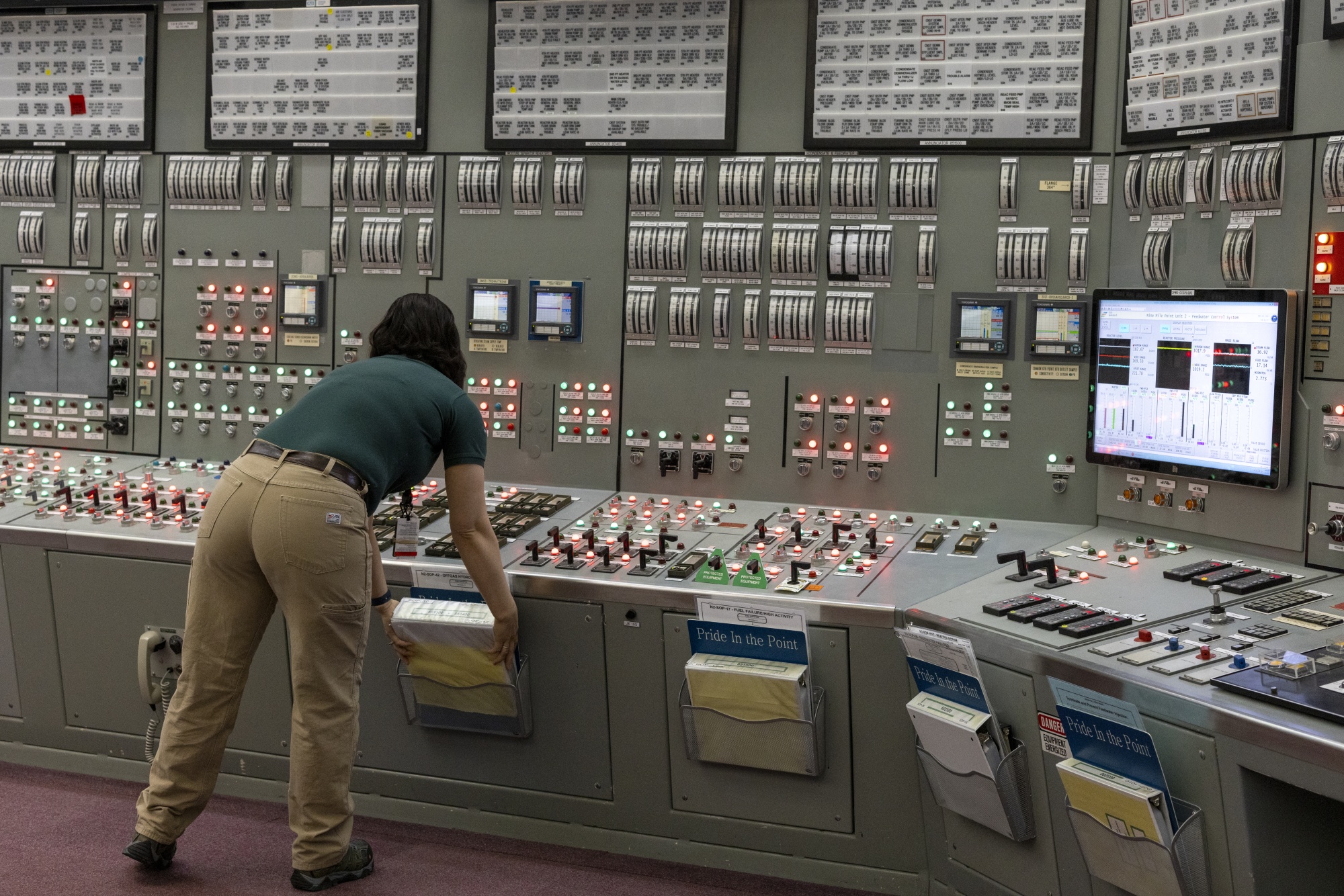

| By Will Wade Constellation Energy Corp. has an ambitious $1 billion plan to produce hydrogen using carbon-free nuclear power. But the plan is on hold — and may be derailed completely — as the company awaits guidance from Washington on a tax credit that's expected to play a key role in efforts to use the gas to decarbonize heavy industries. The US Treasury Department is expected to issue rules in the coming months clarifying how hydrogen suppliers will qualify for a subsidy of as much as $3 per kilogram that's included in the Inflation Reduction Act. The industry has been waiting for guidance since the landmark law was signed in August, and the fate of Constellation's plan hinges on whether the Biden administration imposes strict limits urged by environmentalists and some Democratic lawmakers. Energy giant Constellation is the first US company to produce hydrogen at volume using nuclear energy, at a plant in upstate New York. It's been planning to install the technology at several reactors in the Midwest to supply industrial customers. Factories that make steel, fertilizer, chemicals and other carbon-intensive products account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, and hydrogen produced using renewable or nuclear power can offer a low-carbon alternative to processes that rely on fossil fuels. However, there's a growing push to introduce language in the policy that would undermine the company's strategy. "The uncertainty around the regulations has brought us pretty much to a full stop," Chief Executive Officer Joe Dominguez said in an interview. He said the limits under consideration would threaten US climate targets. "If this doesn't get interpreted correctly, we're not going to have the hydrogen to meet the goal." And the US may need a lot of it. Annual demand for clean hydrogen may reach 10 million metric tons by 2030, driven largely by industrial consumption, according to a March Energy Department report. That amount could quadruple by 2050. Ten million tons is about the same amount of hydrogen that US industry consumes now, for refining fossil fuels, producing fertilizer, food processing, treating metals and other applications. But currently the vast majority is extracted from natural gas, a process that also produces carbon emissions. That's why there's a push for clean hydrogen, extracted from water. The key is that the process must use carbon-free electricity. That could come from wind, solar or hydropower dams — to make what's known as green hydrogen — or from nuclear reactors to make so-called pink hydrogen. Dominguez said the US nuclear industry could supply as much as half the demand in 2030. However, some environmentalists have concerns about using existing clean-energy facilities to make hydrogen. Those power plants are already supplying energy to the grid, but diverting electricity to make hydrogen would mean less clean power on the grid, creating a gap that may be filled with power from natural gas or coal, said Rachel Fakhry, policy director for emerging technologies with the Natural Resources Defense Council.  Hydrogen tanks in a storage area at Constellation's production facility. Photographer: Lauren Petracca/Bloomberg The text of the Inflation Reduction Act bases eligibility on meeting an emissions threshold and doesn't refer to any specific power-generation technology. NRDC has submitted comments to the Treasury Department outlining suggested criteria for being able to claim the full clean hydrogen tax credit known as 45V. Those include restricting eligibility to new power plants. Some options would let existing plants earn the credit, such as nuclear plants operating at night, when demand for power is low, or renewable facilities that began operating recently. "The basic principle is that there should be no increase in system-wide emissions on the grid," Fakhry said. Without "rigorous guardrails," the resulting investment could spur a net increase in US emissions, Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon and four other Senate Democrats warned the Internal Revenue Service in a letter on May 25. Spurring production of carbon-free hydrogen could have significant climate benefits. Not only would it eliminate the emissions associated with the hydrogen that's widely used now, but the gas could also be used in new applications, like making clean steel or sustainable jet fuel. It could be blended with gas to curb emissions when burned in power plants and used in fuel cells to make electricity. But all of that needs clean hydrogen, and the US is currently making less than 1 million tons of it a year.  A reactor operator in the control room at the Nine Mile Point plant. Photographer: Lauren Petracca/Bloomberg Constellation is the biggest US nuclear operator and began commercial production of pink hydrogen in March at its Nine Mile Point plant, north of Syracuse. It's using less than 1% of the site's power to make about 530 kilograms (1,168 pounds) per day. Nuclear reactors often use hydrogen in their cooling systems, and the plant is making enough to meet its own needs, saving the company about $1 million a year. Other US reactor operators make small amounts of hydrogen, but Constellation is the only one doing so at scale, said Bob Beaumont, the project manager. The company is also looking at blending gas and hydrogen at power plants. It ran its Hillabee site in Alabama with a mixture of 38% hydrogen in a test this month, a concentration Dominguez said could probably be increased to "well over 50%." But the company has much bigger goals. It wants to boost hydrogen production 400-fold by adding electrolyzers at several of its Midwest power plants. Dominguez was talking to potential customers as well as equipment suppliers, and was about a month away from announcing signed contracts, he said, when he had to shelve the entire venture after it became clear that the Treasury guidelines wouldn't come out for months and there was a chance that nuclear power wouldn't qualify at all. The uncertainty has paralyzed Constellation's plans, and any rule that limits the credit to new power plants would effectively rule out nuclear plants, said Dominguez. "There's no business case" for building a new reactor, which typically costs billions and takes years, he said. "I'm frankly frustrated this issue has come up. It's crazy." |

No comments:

Post a Comment