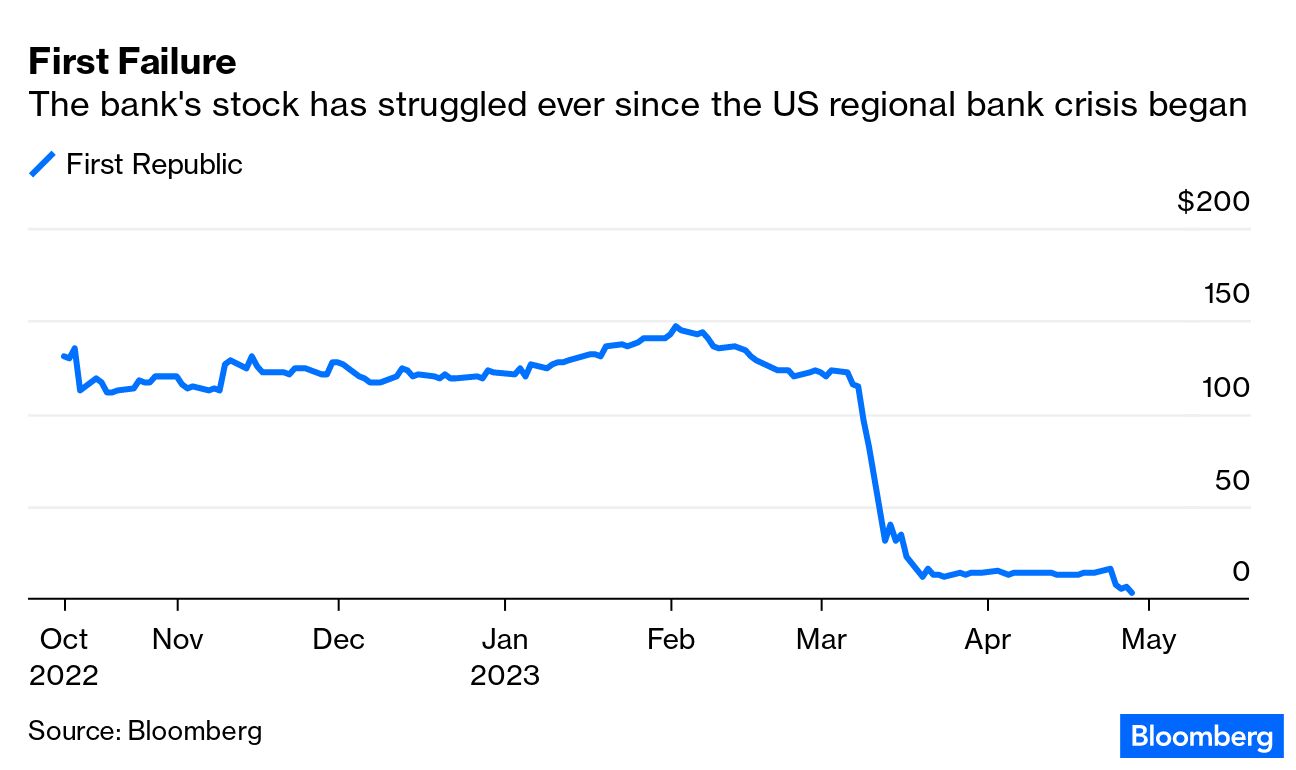

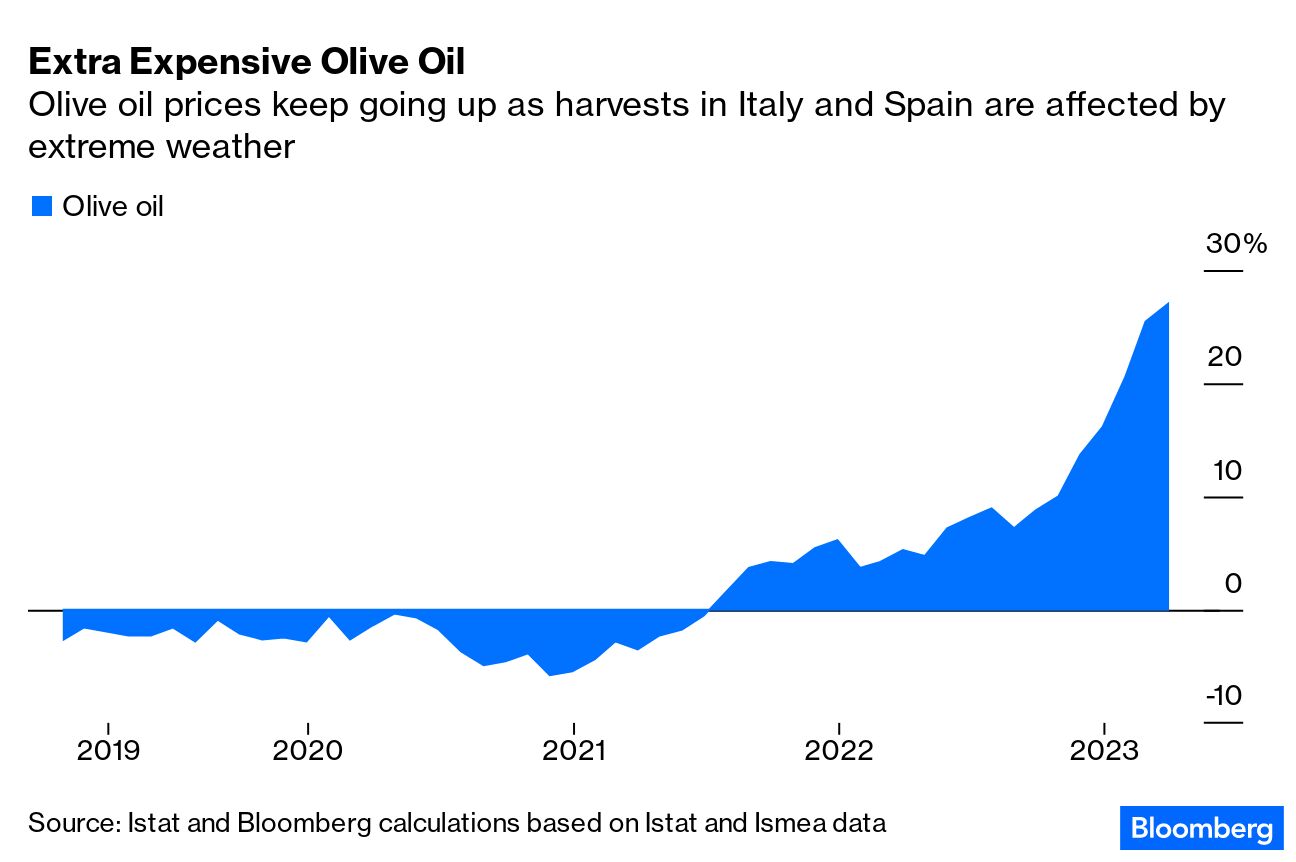

| This is Bloomberg Opinion Today, a fairly homogenous group of Bloomberg Opinion's opinions. Sign up here. This morning at around 1:30, I woke up to two massive booms that rattled me to my core. Was it an earthquake in Manhattan? Or the sound of Jamie Dimon sticking a fork in the regional banking crisis? Neither. It turns out a manhole had exploded right outside my apartment window, and the fire erupting from the earth looked like one of those onion volcanoes at a Hibachi restaurant. Soon firefighters arrived and everything was OK, but the whole episode got me thinking about whether there might be some symmetry between malignant manholes and bank failures. I know, sounds crazy. But hear me out. Since 2012's Hurricane Sandy, New York's Con Edison has been "storm hardening" the grid to avoid widespread power outages. Similarly, after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2008, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, giving US banking regulators more tools to prevent a systemwide disaster. Both of these efforts have worked, to an extent. The grid upgrades have prevented power failure. And the biggest Wall Street banks haven't had any meltdowns in more than a decade. But Con Edison's main aim was to reduce outages — not to prevent manhole covers from exploding. And financial regulators were focused on preventing a 2008-style emergency, which meant giving big banks "stress tests," while pushing small and medium-sized banks to the sidelines. Making matters worse, in 2019, the government loosened rules for midsized banks like Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic, which let them ignore certain losses and liquidity issues. Like the corroded underground cables that rest beneath New York's busy streets, capital standards "have eroded significantly in recent years," Bloomberg's editorial board writes, which is partly why three of the largest FDIC failures this century have occurred in the last two months: Although SVB and First Republic had different journeys to reach their respective solvency crises, the underlying issues that plagued them are the same: They both had "a lot of fixed-income assets held at cost and a high reliance on a fairly homogenous group of uninsured depositors who were highly motivated to watch their money," Paul J. Davies writes. In other words, both banks had ultra-rich, ultra-connected clients: Soon after SVB went under, 11 big banks handed its distressed twin flame — First Republic — a $30 billion loan in the form of unsecured term deposits. It was an unusual display of unity that sadly didn't pan out. Paul says that these financial institutions have since watched First Republic's "slow motion implosion with gritted teeth." Not even the brotherhood of banks could stop the bleeding:  So last night, at precisely manhole o'clock, Jamie Dimon was sprinkling the parmesan cheese on a deal to take over First Republic Bank — which Matt Levine digs into the financial machinery of here. But it was no act of altruism, Paul notes: "After what seemed like an extended game of chicken" between the FDIC and private-sector banks, the FDIC blinked, resulting in an agreement that Mohamed A. El-Erian calls "far from perfect." He argues that Dimon's triumph cements a noticeable shift in the status quo: "The bigger and more diversified banks are now being considered 'safer' than the narrow banks which have either no or a very limited range of capital market activities that have traditionally been viewed as a source of financial stability risk." So what happens when a "too big to fail" institution — formerly a source of ire — becomes the savior of the day? Mohamed argues that it will lead to further concentration of the banking system, which will only serve to destabilize America's already-rocky financial foundation. Others — President Joe Biden and the CEO of JPMorgan, unsurprisingly — aren't as worried. Silvia Killingsworth tweeted that the acquisition should earn Dimon a float in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. Let's just hope that the manholes behave on turkey day. The first of May is a public holiday in a lot of countries, a celebration of workers' rights (and occasionally a protest of workers' frustrations). It got me thinking about one of the great achievements of the labor movement: vacation. I don't want to go all woe-is-me on you, so I'll start with a disclaimer: I'm lucky enough to be employed by a place that offers generous vacation. But many Americans aren't. Whether it's because they don't have a paid vacation policy or the hustle-and-grind culture doesn't allow for it, the propensity to take time off in this country is … pathetic, in so many words. Erin Lowry feels similarly, arguing that "millions of Americans failing to take their full amount of vacation days means that billions of dollars in benefits are being left on the table annually." If you think about vacation in the context of a 401(k) match, you'll get a better understanding of what Erin means. Let's say your employer offers a 100% contribution match on up to 6% of your paycheck annually. Obviously, it's a no-brainer: If you can afford it, you're going to put 6% of your paycheck into retirement so that you don't leave money on the table. The same thing could be said about vacation time: If you're only taking seven of your allotted 15 days, you're literally working eight unpaid days a year. What's often seen as a "strong work ethic" is actually harming, not helping, workers. And it's not just the principle of the thing: Vacation has been shown to lower risks of depression, and provides workers with some much-needed Slack-free R&R. Without the benefit of vacation, both employers and workers are setting themselves up for failure. Erin even suggests that we could separate "personal days" from actual vacation days. Taking a trip to the dentist for your child's fluoride treatment is not the same as hopping on a plane to the South of France. Read the whole thing. A few months ago on vacation (see, I do take time off!!), I visited a family-owned organic winery on the outskirts of Siena, Italy. For biodiversity reasons, they plant a smattering of olive trees around the edges of the fields. The owner of the vineyard told me when it comes time to harvest those olives, the man that's hired to pick them asks to be paid not in money, but in olive oil — the unofficial nectar of the gods — because that's how precious it is. Unfortunately, Lara Williams says olive trees in Spain and Italy are suffering from prolonged heat stress and extreme weather. As a result, olive oil prices are surging — and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.  Texas Instruments might have got a little ahead of itself on the whole chip-shortage thing. After three years of crazy demand, the semiconductor sector is headed for a slowdown. But TI, ever the worrywart, wanted to make sure it had enough product in the bank. Now it's "sitting on a record $3.3 billion of inventories in the middle of the biggest downturn in a decade," Tim Culpan writes. That's enough to cover itself for 195 days, or 6.5 months. You'd think that a calculator company would better at math, but alas. Is it just me, or are America's spies losing their edge? — Max Hastings America has two economies — one for consumers and one for companies. — Conor Sen AI drones are the future of farming. — Amanda Little Only Mitch McConnell can save the US from a debt default disaster. — Matthew Yglesias Social science can explain why King Charles III is key to Britain. — Adrian Wooldridge China might have Covid data going all the way back to October 2019. — Faye Flam A Trump-Biden rematch would prove that democracy is broken. — Clive Crook There's another mystery balloon. Trump is doing a CNN town hall. What to expect when you're expecting a writers strike. Everything you need to know about the Met Gala. A new brain coma study. A new type of marshmallow. (h/t Ellen Kominers) A new way to shower. A new kind of American hero. Notes: Please send color-changing marshmallows and feedback to Jessica Karl at jkarl9@bloomberg.net. Sign up here and follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Twitter and Facebook. |

No comments:

Post a Comment