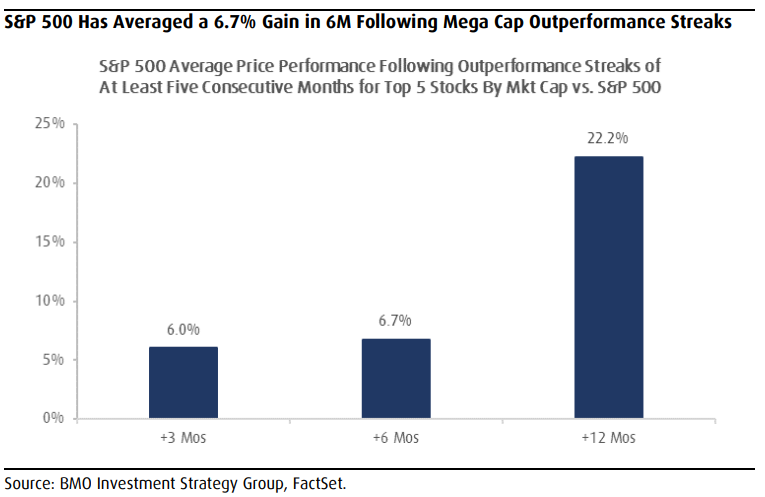

| Tech stocks are back with a vengeance after their dreadful 2022, and have helped lift the Nasdaq 100 higher by a whopping 31% so far this year. They've also given enough of a lift to the S&P 500, the world's most followed index, that it has now twice closed above 4,200, a level that for nine months appeared to be a ceiling. That milestone has given cheer to many. But does it matter that this has been achieved by only a handful of companies? That is the question that hounds investors. Nvidia Corp., whose market valuation flirted with the $1 trillion threshold as markets reopened Tuesday from the long weekend, powered the rally, tacking on nearly 29 points out of the tech-heavy gauge's 56.5 advance. This was followed by Elon Musk's Tesla Inc., which added 19.6 points, and Tim Cook's Apple Inc. at 18.4 points. Those three companies alone accounted for all of the index's gain for the day. All the other 97 collectively were down slightly, despite strong days for mega caps like Amazon.com Inc., Qualcomm Inc. and Netflix Inc. Diversification Is such top-heavy concentration a bad sign? Not necessarily. History shows that the equity upside when it arrives has typically come from a narrow set of companies, said Mimi Duff, managing director at GenTrust. "It feels extreme right now, because we're seeing some of these tech stocks carrying everything, but over a long time period, it is absolutely the case that a narrow sleeve carries the equity returns," she said in an interview. "That's just another reason to be long indices. It's really going to be hard to pick the winners in advance." One of the points of diversification is to improve your chance of holding the best performers in the index. If the index returns are narrow, it only enhances the case for diversifying. With more concentrated holdings, there would be more of a risk of missing the biggest winners. And those winners this year are buoying all the most popular indices. While the benchmark S&P 500 has risen just about 10% for the year (still a great performance), its largest gainers also comprise the exact same stocks as ones that lifted the Nasdaq 100. Such a narrow market does suggest reason for caution. To quote Tony Roth, chief investment officer of Wilmington Trust, it doesn't suggest broad strength. "It suggests that it's idiosyncratic. And that's a reason to believe the equity market is not really giving us a buy signal just because it's broken through the top of the range." Narrowness Isn't So Bad What if momentum begins to wane, as must surely happen at some point? Worry not, said Brian Belski, chief investment strategist at BMO Capital Markets. There's no denying that the rally in mega-cap tech shares is astonishing, but there have been other market advances led by a narrow group of stocks in the past. Once their relative performance has subsided, the broader market has historically held up "just fine with gains being more common than losses." "Putting mega caps aside, we found that narrow market breadth in general does not represent a bad omen for S&P 500 performance despite the contrary narrative being pushed by many investors," he wrote in a note to clients. Put differently, the famous narrow rallies that preceded major selloffs, notably the boom for the "Nifty Fifty" that ended in the early 1970s, and the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000, have tended to be the exception to the rule. In fact, market gains have historically been prevalent once stellar runs by the five largest stocks have ended, with the S&P 500 rising 6.7% on average in the subsequent six months. In 11 of the 12 past periods of narrowing breadth identified by Belski, the benchmark gauge has gone on to record positive price returns, with gains being more frequent than losses in the following months. Stock markets do of course tend to go up most of the time, but the degree of positive performance does suggest that a narrow rally isn't such a bad sign.  This rally, however, has been exceptionally narrow. The five largest S&P 500 stocks by market value have outpaced the benchmark by roughly 30 percentage points over the last five months. According to BMO, this ranks in the 99th percentile of historical rolling five-month relative returns since 1990, with only August 2020 — when mega caps were booming in the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic as investors assumed they would work as protection from economic damage — exhibiting a higher spread. Bloomberg's cross-asset team presented this graph of the S&P 500 equal-weighted index versus the the standard benchmark. So far, equal weight is losing by the widest margin for a calendar year since Bloomberg's data began in 1990. Good performance by the biggest companies isn't unusual, but this does look extreme: — Isabelle Lee Valuation Matters The cross-asset team also crunched the numbers on valuation. Last week, the seven biggest tech firms turbocharged by Nvidia added a combined $454 billion in value over five days, pulling the S&P 500 to a second straight weekly gain. The Big Seven's median gain is almost five times the S&P 500, they wrote, adding that "valuations look stretched, with a price-earnings multiple of 35 that's 80% above the market's." It's possible to attack such an emphasis on valuation as failing to see the obvious possibility of transformative growth. This splenetic comment is from Ken Mahoney, CEO of Mahoney Asset Management: Nvidia's massive run in the market is most likely reflected by the future growth of AI, with a very lofty P/E and price to sales at the moment, but that is the market pricing in that growth. Many naysayers will come out and say oh, such a high P/E, I wouldn't buy here. To those people I would say you should probably get a job in a different industry because you don't know what you are talking about or doing.

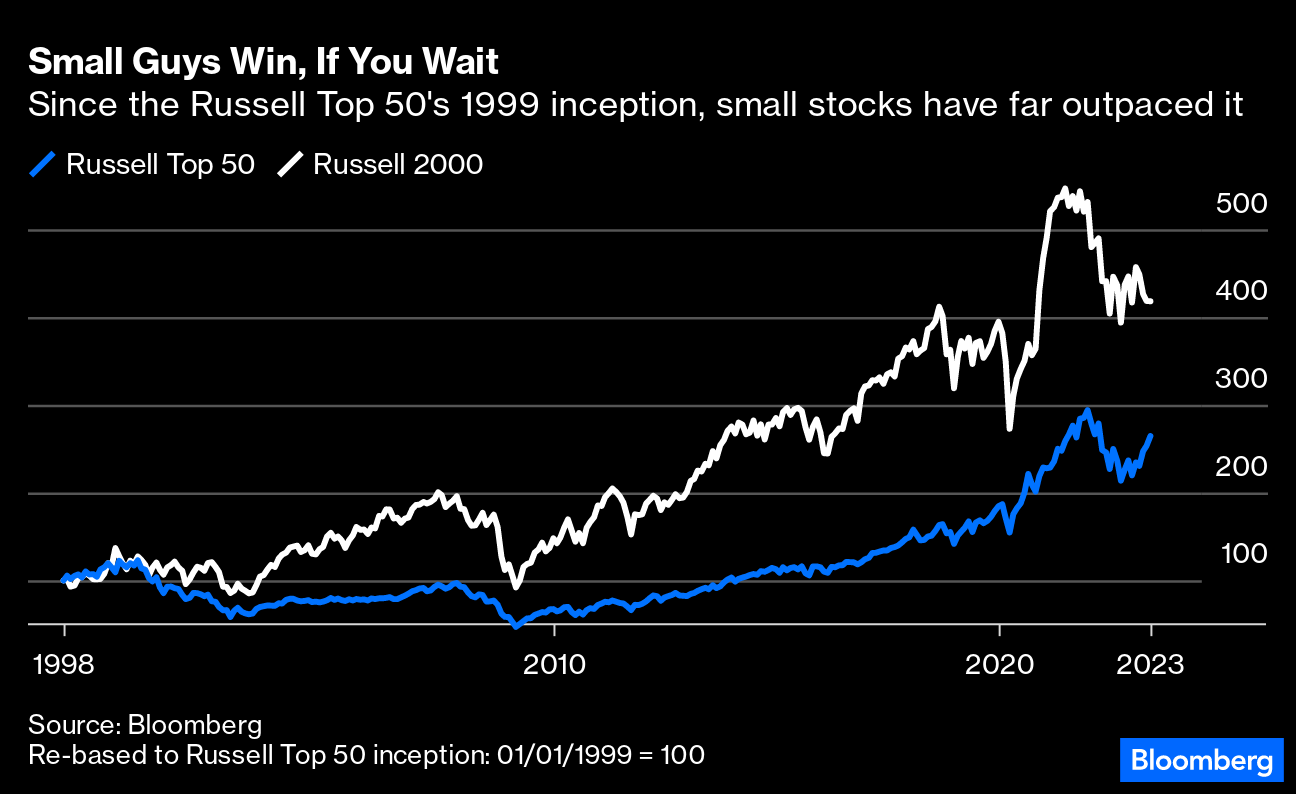

However, this is a tad unfair. Nvidia currently trades at 195 times the last year's earnings. Few large companies ever get to trade at so lofty a multiple. Cisco Systems Inc. traded at a P/E above 200 for three exciting months in early 2000 as investors tried to price in the obvious massive growth potential of the internet, which would need to rely on the company for its pipes and infrastructure. If you had bought at the beginning of that period and held, it would have taken until 2018 just to break even on the investment, and by now, 23 years later, you would be sitting on a profit of 22% — or a compound rate of 0.85% per annum. This terrible return has been achieved even though Cisco's business has grown much as expected. This isn't to say that an investment in Nvidia will work out so badly; just to remind that valuation does matter. Questioning a P/E of almost 200 doesn't disqualify you from working in finance. It also doesn't mean that the sector should be abandoned forever. To Matt Miskin, John Hancock Investment Management's co-chief investment strategist, tech is potentially getting overbought and "may need to take a breather." It's hard to deny the signs of short-term froth around AI. However, to quote Roth of Wilmington Trust, the current enthusiasm may well be justified — it just may need a little more time than some now expect. "The impacts of AI are going to be so profound in the next year or two that it's going to change this economic cycle," he said. "So the AI story is really investing in the right companies that are going to be transformative in the next economic cycle, which will start after the recession. That happens probably later this year or next." Big Versus Small Finally, the standard arguments against investing in large caps apply. Quants have long identified a "small company effect" which finds that in the long term, smaller stocks tend to perform better than larger ones, although with occasional long periods when they don't. That could be because investors are rewarded for the greater risk in the long term, or because the market for small companies is less well researched, creating bargains. Since Russell initiated its Top 50 index of the 50 biggest US companies by market value at the beginning of 1999, this is how it's fared compared to the Russell 2000 index of smaller companies:  A more practical argument is that once a stock has become one of the biggest in the market, its growth tends to be in the past and well understood. Generally, it can be expected to start paying out dividends, but will exit its period of stratospheric growth. That is what happened to several of the companies that spent years as the biggest by market cap, such as IBM Corp., General Electric Co., ExxonMobil Corp. and AT&T Inc. For them, there was no way to go but down. Apple and Microsoft Corp. have been the two biggest stocks with only brief interruptions for a decade now. They are great companies, but odds are stacked against their continuing to outpace the rest of the market for another decade. So if history is a guide, it's best to be careful before investing in mega caps at a time like this. But it's also true that there's no reason why the broader market can't move forward after a period of such narrow breadth. Should the aim of economic growth be to create more stuff, or to give us the chance to spend less time working? Either is a valid choice, but it's fascinating to see how different the decisions of the US and Germany have been. Americans are spending as much time working as they ever have, and it's never really altered much. The hours worked by Germans, meanwhile, have declined almost as reliably as GDP has risen. Two generations ago, they spent much more time at work than Americans; now they spend much less: There's a very good chance that AI will drive an improvement of productivity. That would mean fewer worker-hours would be needed in total. Might the US take the opportunity to offer jobs with shorter working weeks? German experience makes clear that this can be done. The pandemic has already transformed working life for white-collar workers. If AI delivers on the scale that now seems possible, there could be more revolutions in the world of work ahead of us. Some podcast suggestions. For years, "Talking Politics," fronted by the Cambridge professors David Runciman and Helen Thompson, was one of the best out there for well-informed and intelligent discussion of international politics and its interaction with the economy. They decided to quit while they were ahead, and now both are back with their own new podcasts, which are off to great starts. Runciman can now be heard on Past Present Future, and in the most recent episode discusses artificial intelligence. Thompson's new perch is called These Times, most recently discussing the history of immigration. They're both excellent if you like long-form listening. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg: - Clive Crook: High Inflation Isn't Entirely the Fed's Fault

- Olga Kharif and Emily Nicolle: Winklevoss Twins Attempt Pivot After Gemini Loses Money and Employees

- Javier Blas: Saudi Aramco's $2 Trillion Valuation Is an Illusion

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment