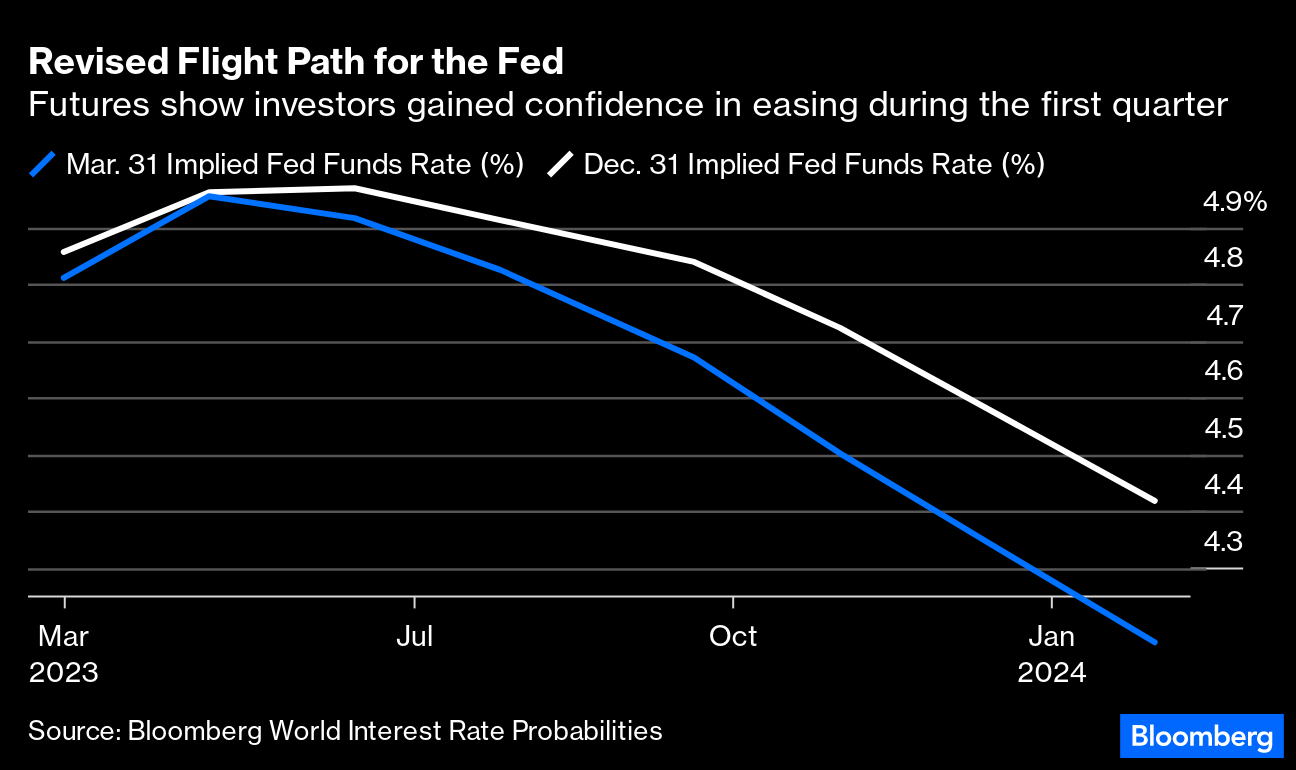

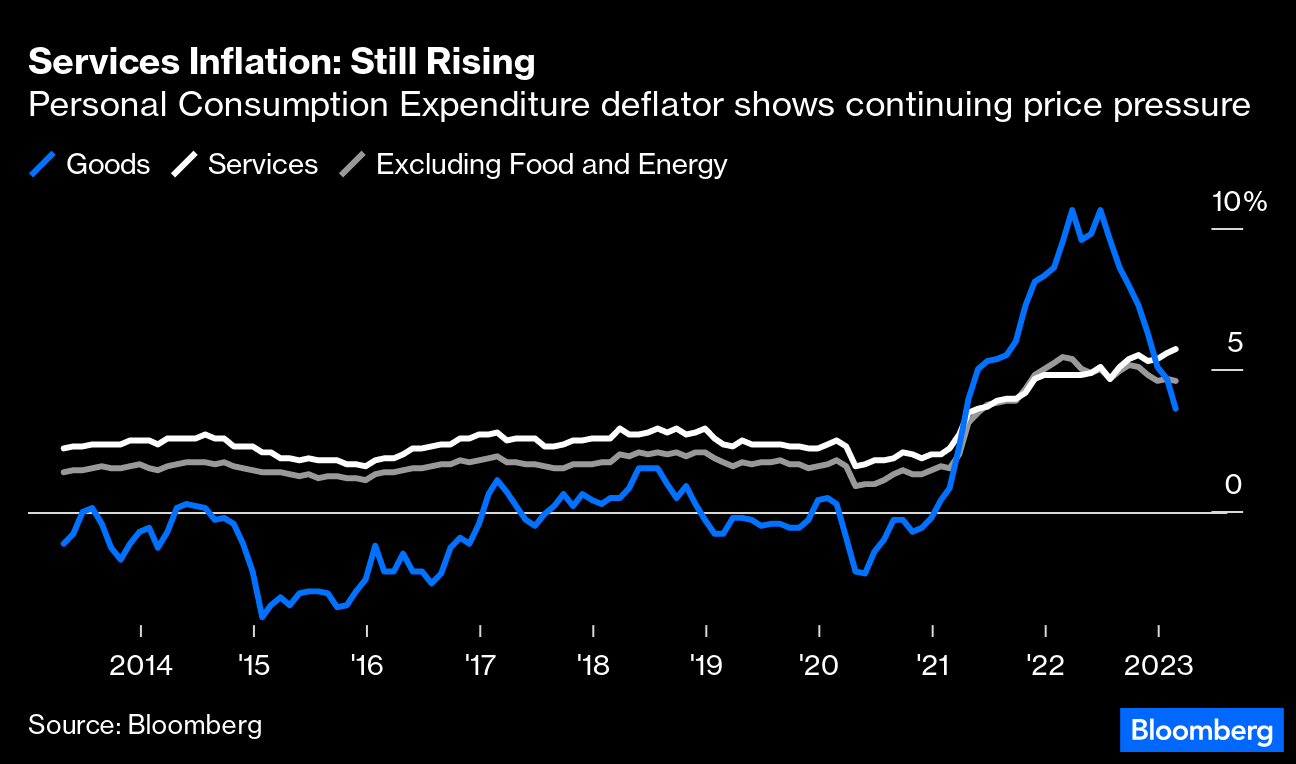

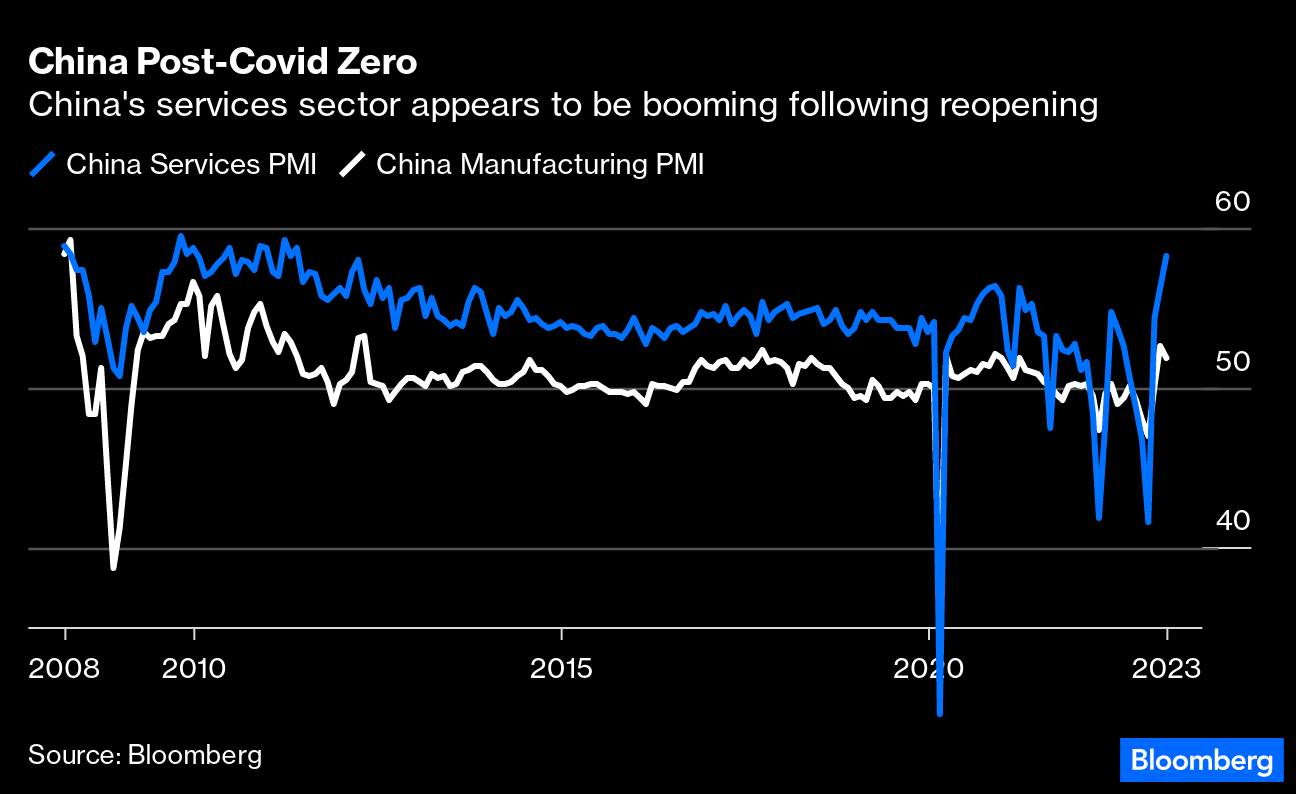

| Three months ago, very few asset managers can have imagined that Silicon Valley Bank would change the direction of world markets (admittedly with help from Credit Suisse Group AG, which had long been a target of short sellers). But the bank, of which many outside the tech startup community had never heard, appears to have turned expectations on their head as the second quarter begins. Is this right? To start, let's compare the market's implicit expectation for the course of the fed funds rate on New Year's Eve with its forecast as of April Fools' Day. Bloomberg's World Interest Rate Probabilities function shows that confidence in significant rate cuts before the year is out has grown:  On the face of it, this would imply that inflation is coming under control a little ahead of schedule, creating space for the Federal Reserve to ease the pain a bit early as well. But that isn't what is happening. The last day of the quarter brought the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) measure of inflation that the Fed takes as a benchmark. The data takes a month to compile, so it is backward-looking and tends not to move the market as much as other yardsticks of prices. But it doesn't show any significant deceleration and instead backs up the picture from the consumer price index data. Inflation in services, not goods, is now the chief problem. Core inflation measured this way, excluding food and energy, edged down very slightly, but not in the kind of way that might allow the Fed to reverse course within months:  Using a statistical measure beloved of the Fed, the "trimmed mean" — which involves removing the biggest outliers in either direction and taking the average of the rest — also confirms a picture of inflation that has slowed down very slightly, but is still too far above target to justify a change in policy. It's calculated by the Dallas Fed, on both a monthly and a year-on-year basis: It's not, then, because of any improvement in the inflation picture that people now expect a more lenient central bank. And China, so often an explanation for economic data in North America and Western Europe that don't seem to make sense, is also nothing to do with this. As the year turned, it was reasonable to worry that a wave of Covid-19 would thwart an economic rebound. Judging by the latest purchasing manager data, that hasn't happened. And thus, the urge to loosen monetary policy elsewhere should be less:  So why the extra conviction that the Fed will have to ease? The answer, of course, is the banking crisis. The last month saw Silicon Valley Bank become the biggest US bank failure since 2008, and Credit Suisse forced into a shotgun wedding with its rival UBS Group AG. When banks are in trouble, in general everything else in the economy should beware. The current rate expectations reflect three weeks of trying to come to terms with the banking seizure and the regulators' response. They also reflect an average formed from very different opinions about the next year. Ajay Rajadhyaksha, global chairman of research at Barclays, points out that the market is pricing in a 12% chance that the fed funds rate will drop down to 2% by the end of this year, a level that would imply a very serious economic slowdown. There are plenty who don't think the Fed will ease at all. To capture how much forecasts have moved, this is the implicit expectation for the fed funds rate after January's Federal Open Market Committee meeting, and how it has moved over the year so far: If this represents negativity about the economy, that is in line with more qualitative surveys. The Absolute Strategy Research survey of asset allocators for the second quarter has just been released, and is based on interviews that took place during the worst of the banking upheaval. Putting together respondents' predictions on a range of market indicators, it found the deepest pessimism since the survey started in 2015 (a period that includes the Chinese devaluation that year, the Brexit referendum, and the Covid-19 pandemic): This is driven primarily by concerns about financial stability. The March edition of the survey of global fund managers run by Bank of America Corp., based on surveys that took place over a time that included the beginning of the banking troubles, showed a sharp increase in perceived risks to financial stability. Remarkably, those risks are perceived to be even greater than at any point during 2008: Concerns on this scale, if justified, certainly would entail a much easier monetary policy. In the process, they also imply that the Fed's battle against inflation will be traduced. That makes it more popular to bet on securities that might actually benefit from higher inflation, such as precious metals. Larry McDonald of Bear Traps Report puts the dynamic in dramatic terms: As the credit crisis moves toward its next set of victims, the Fed policy path is now under house arrest. This outcome highly favors a) value equities, b) emerging markets, and c) precious metals. The beast inside the market has Powell's Fed in a headlock. It has been a VERY long time since the Fed softened the path with inflation expectations this high.

Don Rissmiller, chief economist at Strategas Research Partners, suggests that the scale is at the very least tipping against further rate hikes, with the balance of probability now moving toward an imminent pause: Bottom line: We continue to believe a Fed pause makes sense now since 1) there have already been swift & significant rate hikes; 2) policy is looking restrictive as things are breaking (eg, banks, home prices); and 3) if inflation slows, as we expect, real interest rates should continue to automatically climb.

As it stands, then, prices enter the second quarter on the assumption that the banking seizure has been a game-changer for the economy. That in turn, I would argue, implies that the risks are skewed strongly toward rate expectations moving upward from here. That's for two reasons. First, the banking crisis isn't as damaging as first thought. And second, even if the sector requires more help to ease it through, central banks won't necessarily provide that help by cutting rates. At the worst of last month's crisis, all the world's major central banks hiked rates regardless. That should be taken as a signal of intent, and of a belief that they can separate mainstream monetary policy from the specific tools needed to buttress the banks. For a notion of how serious the US crisis is, it's worth looking at this great piece of data visualization from Bloomberg Opinion's Paul Davies and Elaine He. The banks that ran into trouble were outliers that had made themselves hugely exposed to rising interest rates. This is one of several charts in their piece that makes clear that disaster for these banks does not necessarily imply disaster for the entire financial system: Is it reasonable to hope that the crisis stops at this point? The most recent evidence looks positive, with no significant further flight of deposits, and with banks' share prices recovering. To the extent that a banking crisis is driven by panic or loss of confidence in itself, this looks like a good sign that the crisis has been halted. Further, the terms on which the Fed has tried to deal with the central problem of banks' liquidity look "shockingly generous," to quote Barclays. Banks, like SVB in particular, that invested heavily in long-dated bonds are not now able to sell those investments without taking a big capital loss because their price has dropped. This is not a problem if they are held to maturity. So the Fed's offer of a program to lend against bonds as collateral, on the assumption that they are still worth their face value or "par" is generous. It eases any liquidity issues. "There's not remotely a question of solvency," says Rajadhyaksha of Barclays, who suggests that financial markets have "underestimated how hyper-concentrated the deposits were in those few banks that were in trouble." Second, it's important to look at how serious an effect the banks will have on the economy. Obviously, this would change if one of the biggest systemically important institutions ran into problems, but reasonable estimates at present suggest that the damage should not be that great — and also that Europe might suffer a more negative impact than the US. After a stress test that involved adding the tightening of lending conditions to the raising of policy rates that has already happened, Silvia Ardagna of Barclays said the effect would be noticeable, but not overwhelming. Tighter lending standards as a result of the banks' problems would reduce GDP growth by about 0.25 percentage points. "In December 2021, bonds were pricing a fed funds rate of 90 basis points by the end of 2022," said Rajadhyaksha. "The bond market does get things wrong. We think the fed funds rate is unchanged through the end of the year."  Shoring up confidence in banks by the Fed "shockingly generous." Photographer: Al Drago/Bloomberg There is the further issue that central banks have been deploying two weapons against inflation. Beyond interest rates, they have also tried to affect liquidity more directly through quantitative tightening (QT) — selling bonds into the market, in a maneuver that reduces the amount of money in circulation and tends to push yields upward. The measures taken so far plainly run counter to this. It's possible for central banks to abandon QT, or even resort in effect to a return to QE (quantitative easing) by buying up bonds, while at the same time keeping rates high. Tony Roth of Wilmington Trust suggests as follows: We think that it's actually a good possibility at the next Fed meeting they slow down the pace of quantitative tightening in order to provide more assurance on financial stability. But that is not a reason for them to cut rates because it's not necessary.

The only way they would cut rates would be if either they need to for financial stability, which is not the case, or the super-core rate of inflation comes down in consecutive months so that they have confidence that they're headed towards 2%. And we don't see that happening yet. We don't see the labor market supporting that. The labor market remains very, very tight. We're moving in the right direction, but we're not moving so fast that we would expect to see a cut cycle later this year. And that's why we're underweight equities and we feel that the market is being a little bit too optimistic right now.

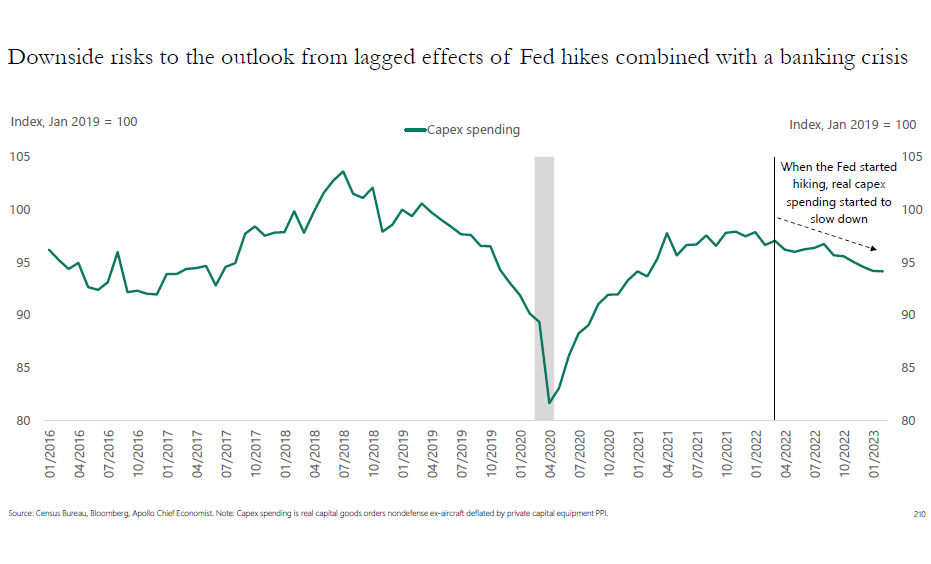

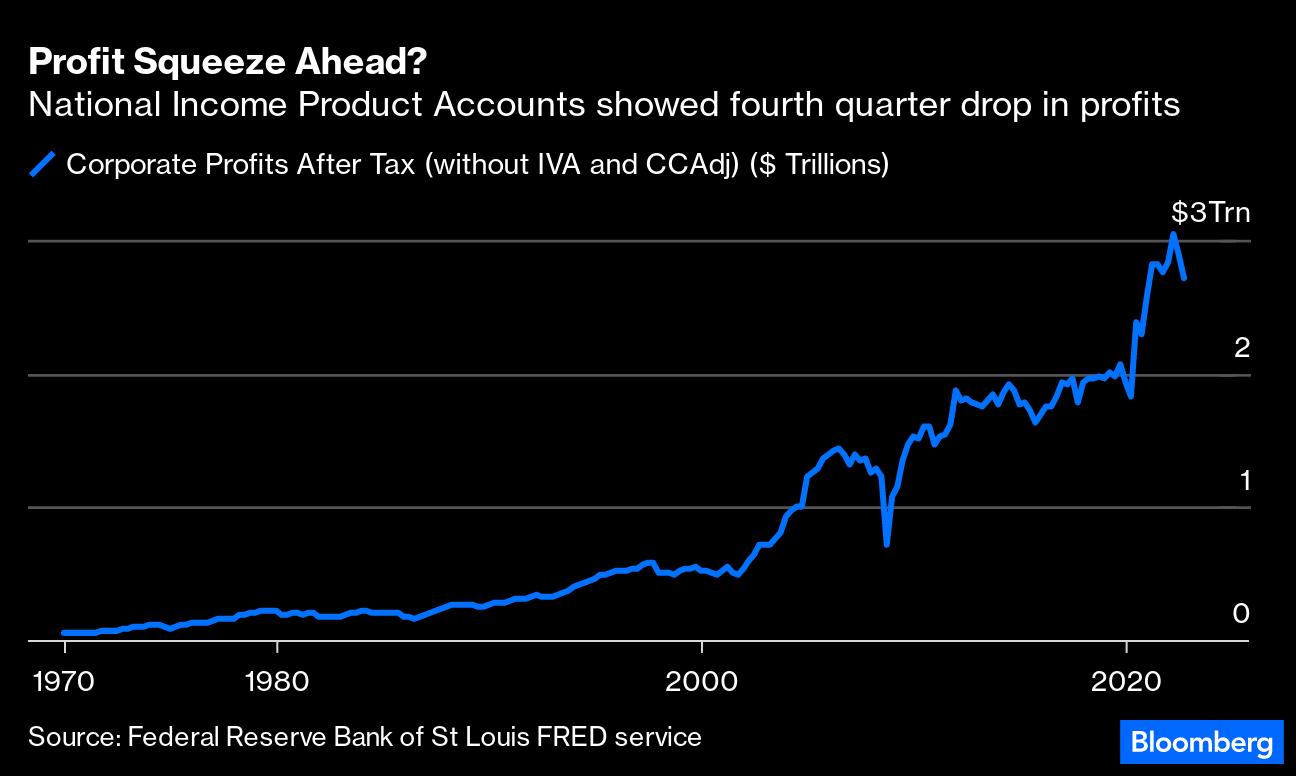

In the short term, the risks are that markets will continue to shift away from the position of the last few weeks, and perhaps begin to put some credence in the Fed's claim that it won't be cutting rates this year. A barrage of data that is about to hit for the beginning of the month should enlighten us further. While the banks' crisis might not hurt economic activity that much, tighter money can be expected to have a big effect, with a lag. The most important place to look for that could be the corporate sector. As Torsten Slok, chief US economist of Apollo Management, shows in this chart, capital expenditures (capex) have started falling. That can be expected to have a negative multiplier effect over time, which would be good for defeating inflation, but not so great for economic activity, or corporate revenues and profits:  And on the subject of profits, the latest National Income Profit Accounts data, compiled as part of the process of calculating gross domestic product, came out last week. This is a measure of corporate profits that eschews the smoothing that goes with the GAAP accounting used to publish companies' accounts. They're typically published, as below, with adjustments both for inventory valuation (IVA) and capital consumption (CCAdj). Over time, NIPA profits and S&P 500 GAAP profits do tend to move roughly together, because there are limits to the creative accounting that companies can do. But in the short term they can differ. It's therefore not a great sign that NIPA profits took a dip in the final quarter of last year:  There are reasons for concern about the remaining three quarters of this year, many of which are not yet reflected in market pricing. For now, however, it looks as though the damage done by the banks has been overpriced. Absent big surprises in the new data — or fresh external shocks like the Opec+ agreement to limit oil production that spurred a rise of 8% for Brent crude at the Asian opening — it's best to brace in the near term for bond yields to rise from where they are now, while more speculative investments give up ground. —Reporting by Isabelle Lee Schadenfreude, it turns out, isn't as much fun as all that. In the ridiculously cutthroat world of English soccer, 13 Premier League managers have been fired so far this season. There are only 20 clubs in the league. This weekend brought two sackings, including Graham Potter, who was only hired by Chelsea earlier this season after they fired their previous manager (barely a year after he'd led them to victory in the European Champions' League). There are many angles to this. Chelsea were notorious for the speed with which they fired their managers when run by Roman Abramovich, a Russian oligarch. Not a year has elapsed since he was forced to sell to a group led by Todd Boehly, an American private equity guy, and already the new management has fired two coaches. More intriguingly for me, Graham Potter used to manage my team, the deeply unfashionable Brighton. Potter took them to ninth last season, their highest finish in a history that stretches back more than a century. In his last year, Brighton managed to beat a Manchester United team featuring Cristiano Ronaldo, winning 4-0 and 2-1. His last game in charge saw Brighton score five in the top flight for the first time ever. But things haven't worked out for him at Chelsea, where the owners lack patience. At the time of writing, Brighton are five places above Chelsea in the league standings. So this should be hilarious. But it isn't. He's a decent and very talented man who accepted an offer he would have been mad to reject. I thoroughly dislike Chelsea (but then I always did); I don't take any pleasure in the way things have worked out for Potter. On which note, try two classic songs by Brightonians — Tom Hark by the Piranhas, and Praise You by Fat Boy Slim. And I suppose you could also listen to Joni Mitchell's Chelsea Morning (which helped Bill and Hillary decide on a name for their daughter). Good luck for the future, Graham, and good wishes for the week to everyone else. More From Bloomberg Opinion: |

No comments:

Post a Comment