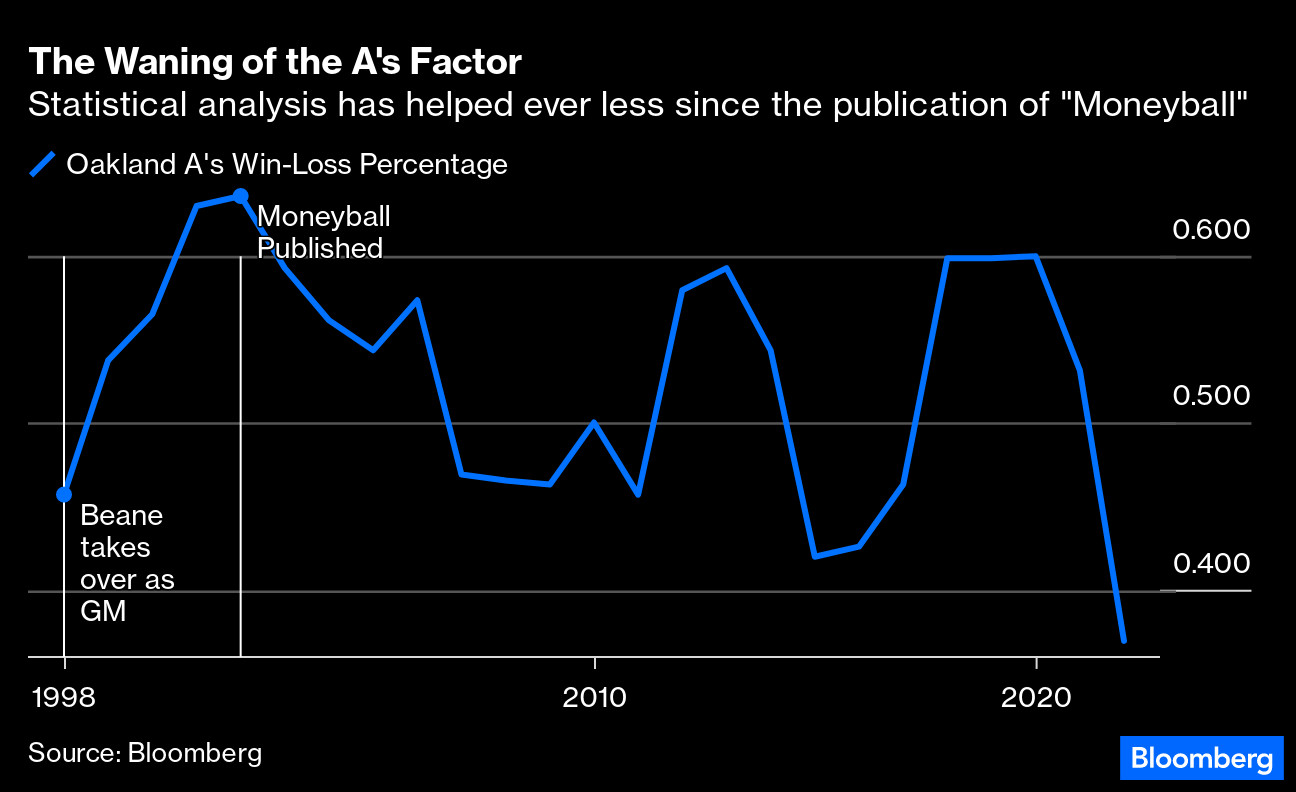

| Baseball is back. Opening day is one of the most blessed days in the American calendar, as winter ends and baseball starts its 162-game season that will be the backdrop for the summer. It's a time of renewal, and also of timelessness. Baseball has been played in recognizably the form it's played now, with two teams of nine confronting each other on a diamond, for more than a century. There's something deeply reassuring about its familiarity and the way it carries on, serene and unchanged, amid a disorderly and changing world. Except this year, the rules have been changed. That's happened to counteract statisticians' increasingly brilliant use of data to guide teams. This has changed the way the game is played, and steadily made it slower and less exciting (a development those who never liked the sport might say didn't change much). And all of this has very direct implications for the world of investment. Baseball, like investment, has always been drenched in statistics. For many decades, small boys have been memorizing batting or earned-run averages from the back of baseball cards, just as investors work their way through price/earnings ratios and dividend yields. In the 1990s, that statistical analysis grew much more sophisticated. In a way immortalized by Michael Lewis's book Moneyball, which was turned into a movie with Brad Pitt, the general manager of the low-budget Oakland A's, Billy Beane, exploited statistical attributes that had been underpriced by the rest of the market. In particular, the ability to get on base in any way possible turned out to be useful and undervalued. Like a classic value investor, Beane "zigged when the market zagged," and bought up unappreciated players expert at getting on base to produce teams that regularly did far better than their payroll should have permitted. The book made a star of Kevin Youkilis, whom Beane had spotted had a brilliant ability to draw a walk (though he never played for the A's). Youkilis indeed became a star in a championship team for the Boston Red Sox.  Kevin Youkilis plays being Kevin Youkilis against the Toronto Blue Jays. Photographer: Abelimages/Getty Then Theo Epstein applied the same model with a large budget to achieve the almost unthinkable — putting together teams to win the World Series for the Red Sox (in 2004, for the first time in 86 years) and then for the Chicago Cubs (in 2016, for the first time in 108 years). Legend had it that both teams were victim to some kind of supernatural "curse"; Epstein showed that a dispassionate quantitative approach could deal with all of that. In the last decade or so, the data revolution has gone further. Everyone knew about the statistics that Beane had used, so the anomaly in pricing disappeared. Players who got on base commanded higher salaries. A statistical arms race got under way. Cameras and faster computer processing now allow managers to delve into the internal mechanics of the game. They can break down the success batters get from hitting the ball at different "launch angles," or the change in run-scoring probabilities if fielders are shifted from their traditional slots, or the most effective way to change pitchers to limit scoring. The result is a game with very little action and excitement, in which batters don't swing that often. There are lots of home runs, and little else. Purists might find it exciting. Most don't. Meanwhile, Beane's A's, deprived of their edge, won only 60 games last year, for a .370 winning percentage.  All of this led to this year's rule changes, which have been masterminded for the league by Epstein. Both pitchers and batters have to go about their business quickly. If they're not ready when time runs out, they're penalized. The bases are bigger, making them easier to get to — and steal. There are limits on how many fielders can be on one side of the field. Add all this up, and the incentive to try to hit the ball somewhere within the park and then sprint toward first base is much greater. Teams with fast base-runners and agile defenders, and pitchers who can work quickly, will be at a greater advantage than last season. Those who have found a way to win within the old rules will have to go back to the drawing board. Some team somewhere is going to do much better than expected because the new rules play to their strengths. Over the years, the quants will work out how to win. But for the time being, if everything works as intended, the game should get more exciting. Now, at long last, for investment. The relevance of all this should be immediately apparent. Michael Lewis is most famous for his books explaining finance (most notoriously Liar's Poker), and he used those skills to explain baseball stats. Billy Beane is a keen value investor. And there is an analogy for the stages of progression in baseball. First came indexing — the notion of minimizing costs by just passively investing in the index. It was based on the theory of efficient markets, that prices would always attempt to incorporate all known information. From this came factor investing. Most famously, Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago and Kenneth French of Dartmouth College went through massive empirical work to identify different factors that show a repeated tendency to beat the market in the long run — such as value (cheap stocks do well over time) and momentum (winners keep winning and losers keep losing) — and invest in them passively and systematically. That came to be known as "Smart Beta." These days, it's possible to offer such factors in a simple exchange-traded fund, and it's hard to get clients to pay a fee for them. Now, it looks like the quantitative arms race to find systematic ways to beat the market is moving on. In what is likely to be a controversial finding, Jay Rajamony, head of alternatives at Man Numeric, says that all the most popular factors are in long-term "decay." This suggests that the fund management industry must have been doing something right. But it makes it harder for them to justify charging a fee, just as the Oakland A's find it harder to attract fans than they used to. The following chart shows how a portfolio allocated to different factors roughly in proportion to their popularity in the quant community would have performed compared to the broader markets in a range of geographies since 1996. It's rebalanced monthly, and adds to the simple Fama and French factors (which you can find updated on Ken French's website, something of a Rosetta Stone for the investment research community) by incorporating extra measures. For example, it includes several measures of value, and not just the price/book multiple that Fama and French used in their research. The trend in factors' efficacy is obvious: The problem with factors is that they tend to be cyclical — value and growth both go through long cycles — and to get overcrowded. Most critically, as quants get better at their job, their efficacy tends to be arbitraged away; enough managers jump into value stocks, or get on board momentum, that they don't perform as well as they once did. There followed an unholy rush in which academics and teams of quants attempted to identify new factors. One extraordinary research paper from 2016 found 316 separate factors that had been promulgated in the academic literature. The tendency for them to lose all their efficacy as soon as they're revealed to the world is strong. Academics have also managed to demonstrate that academic research destroys stock return predictability.

In what sounds rather like the fate of Billy Bean's A's after other teams read Moneyball, Rajamony says: The main takeaway is that efficacy is declining over the long term. Nobody is saying these concepts aren't relevant. They all still matter. But as soon as a particular definition becomes prevalent and widely used, there's more attention to it and that factor begins to atrophy.

The obvious common trend is that factors are decaying, although that decline apears to have been halted in the US and Europe. The fact that factors continue to erode in Asia and the emerging world tends to support the notion that they're rooted in relative market inefficiency. Big anomalies have steadily been eradicated. Others try to strike a different balance. Savina Rizova, global head of research at Dimensional Fund Advisors, (a disciplined quantitative investor which as it happens has also been the subject of a brilliant Michael Lewis article) contends that factors that are rooted in economic or valuation theory can be expected to continue to deliver returns. "We do believe the main driver is risk. The reason why is that if they weren't based in risk, you would see lots of free lunches out there." While it remains riskier to invest in stocks rather than bonds, or smaller rather than large companies, or cheap firms, on this argument, factors will continue to work. For Dimensional, it remains important to use extra sources of data when they're available. And that is where quantitative investing is now going.  Author Michael Lewis at a conference. Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg David Blitz of Robeco Asset Management calls this "next-gen factor investing," which can involve mining data on such things as financial transactions, sensors, mobile devices, satellites, public records, and the internet. "Text data — such as news articles, analyst reports, earnings call transcripts, customer product reviews, or employee firm reviews — can be converted into quantitative signals using natural language processing techniques that are becoming increasingly sophisticated." This can be viewed in baseball terms as the leap from analyzing traditional data more smartly to getting out cameras and laser guns and analyzing the angle at which players hit the ball. It involves making the collection of the data itself into a source of competitive advantage, and prompts Blitz to claim that "the best is yet to come" for factor investors. The new data that quants can crunch can even, he argues, be seen as an extension of what they were already doing: "Traditional value factors have been criticized for only including tangible assets that are recognized on the balance sheet, while many firms nowadays have mostly intangible assets, such as knowledge capital, brand value, or network value. For estimating the value of knowledge capital, for example, one could consider patent data."  Theo Epstein's Chicago Cubs defeated the Cleveland Indians, 8-7, in Game Seven of the 2016 World Series. Photographer: Ezra Shaw/Getty Must this suffer the same fate as the baseball quants who worked out how to maximize the chance of hitting a home run? Financial quants have the advantage that there is no league commissioner who can set Theo Epstein on them and change the rules. But they do face the problem that the arms race will continue to escalate. Once everyone else has the same data, it will be necessary to spend even more money on even more esoteric data. With nobody to change the rules, the market will get ever harder to beat. Meanwhile, in baseball, the new rules seemed to work on their first day, and at least one result on Opening Day went much as statisticians might have predicted. With Kevin Youkilis now installed in the commentary booth, the Red Sox found a way to fall agonizingly short to the Baltimore Orioles and lose 10-9 — but they managed to do it within 3 hours and 10 minutes. That's quick for a 19-run game. Hopes for the US to avoid a recession this year were quickly dashed this month as regional banking turmoil prompted people to pull out their cash from bank deposits. Even as the Federal Reserve gives its best attempt to engineer a so-called soft landing, its track record of tightening monetary policy while averting an economic downturn leaves much to be desired. Recessions in the world's biggest economy have historically provided a headwind for emerging markets. Does this mean that investors who think the US economy is recession-bound must avoid EM? The question is how much of a headwind the US might create. Calculations by the UBS Chief Investment Office show that over the past three decades, EM stocks corrected more than 20% during such periods, translating to a 3% underperformance against their US peers. However, emerging stocks may overall be less affected this time than in the past, strategists including Xingchen Yu wrote in a March 27 note: Emerging economies have become increasingly exposed to the idiosyncratic opportunities in China and Asia given the region's rapid over the past years… We think economic expansion along with continuing policy support in China should provide demand support to the emerging world through various channels, implying a wider real growth differential against developed markets.

The following graph shows that EM stocks come under pressure during recessions in the US. Whatever is bad for Americans is even worse for people in the emerging world: This time around, EMs are proving resilient despite the recent downtrend — with manufacturing PMIs sitting comfortably in expansion territory and economic data from China suggesting the post-Covid recovery is on track. Here's more from UBS: We think such growth dynamics should gradually trickle down to a recovery in corporate earnings. We forecast low single-digit earnings growth for MSCI EM in 2023 and a high single-digit expansion in 2024... In addition, some important external headwinds for EM look likely to fade. As the Federal Reserve approaches the end of its tightening cycle, the probability of an extended period of US dollar weakness increases, and real interest rate seem likely to peak.

They also have some kind of tailwind from bullish investors. After years of lagging, this month's Bank of America Corp. survey of global fund managers found that respondents strongly tended to be overweight in emerging markets. But is that enough? The chart below shows the ratio of the MSCI EM Index and the MSCI World Index (which covers developed markets) for the past six months, which since the beginning of February has traded below its 200-day moving average. After a brief rally, this means emerging markets are underperforming relative to the world gauge: Jitters have been more far-reaching than many thought. Citigroup Inc. strategists including Donato Guarino said in a Thursday note that clients are worried about the degree of contagion EM should see from developed market bank failures, as well as the rising risks of a global recession: The overall tone from investors was cautious, but not overly bearish. Cash levels appear adequate, and institutional flows have been balanced, in contrast to retail outflows. Credit quality and sector exposure is receiving greater scrutiny, which should be expected as portfolios prepare for a potential recession. Also, the relative value proposition of EM vs DM is seen to favor DM at the moment, despite decent fundamentals for most EM corporates.

Emerging markets stole the spotlight at the start of the year buoyed by a weakening US dollar and the reopening of China. And even if the dollar has depreciated from its 2023 peak, that wasn't enough to help lift the EM index. Historically, the two have had an inverse relationship. Another area that stands to benefit from a sliding greenback is emerging debt. A weaker dollar makes it easier for emerging markets to repay their dollar-denominated debt. Here's Marcelo Assalin, head of William Blair's Emerging Markets Debt Team, who thinks the overall global macro backdrop should still remain supportive of EM debt fundamentals. He wrote: China's reopening improves prospects for global growth, outweighing concerns about a US economic slowdown. Commodity prices, while below the peaks seen over the past couple of years, remain at levels that continue to benefit exporters… We anticipate favorable economic conditions, stable fiscal and debt dynamics, and supportive external accounts in most regions this year.

Many different narratives are unfolding in the emerging world, which after all includes plenty of very different places. But even after the March tumult, it's still perceived as a bright spot. Providing the banking sector doesn't send the developed world into all-out recession, which begins to seem less likely, the optimism does seem justified. —Isabelle Lee Breaking up is so very hard to do. And so is putting together a comprehensive playlist of breakup songs. You can find the Survival Tips breakup playlist on Apple and on Spotify. It runs to more than four hours, but that doesn't mean it included everything it should have. Late-arriving but deserving nominations include: Too Far Down by Husker Du; Ne Me Quitte Pas (Don't Leave Me) by Jacques Brel; La Golondrina (The Swallow, a traditional Mexican song) as performed by Placido Domingo; Toi by Gilbert Pecaud; Sexo, Pudor y Lagrimas (Sex, Shame and Tears) by Aleks Syntek; One For My Baby (and One More tor the Road) by Frank Sinatra; (My Heart Is) Closed for the Season by Bettye Swann; So Long, Marianne and Hey, That's No Way to Say Goodbye by Leonard Cohen (and Julie Felix); Leaving Me Now by Level 42; Where Were You When I Needed You by the Grass Roots; The Letter by Natalie Merchant; and Don't Leave Me This Way by Thelma Houston (to go with the Communards version we already had). It's been fun, and I'm still happy to receive more nominations. Have a great weekend everyone. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment