| MTG vs. ESG It's a pity to give more publicity to Marjorie Taylor Greene. The outspoken Republican congresswoman from Georgia gets far more than she deserves. But her recent utterances offer important clues on the future of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing, and cannot be ignored. She made yet more headlines last week by proposing a "national divorce" of blue and red states, which read a lot like a call for secession. But what could matter more is that ESG investing has somehow found its way onto the list of culture war grievances. She tweeted on Monday last week: National divorce is not civil war, but Biden and the neocons are leading us into WW3, while forcing corporate ESG and gender confusion on our kids.

On Tuesday she opined: The left is not going to just give up forcing gender lies & transitions on kids, abortion birth control, ESG, Climate cult lies & the green new deal, the war on police, open border policies, legalization of drugs, identity politics, & more.

Next day came: We must abolish ESG, it's ruining everything. The only score businesses should have is their customer service score. If the customer is happy then you get a good score!

I'm quoting her not because she makes valid points, but also not to ridicule her. She is now one of the most powerful and popular politicians in the US, who has shown a great ability to get people angry about things. Now that ESG has finally emerged as a hot-button partisan, cultural and political issue, the prospects for global investing just got much more fraught. And that doesn't just mean ESG investing. First Principles ESG as a name has been around for about two decades, succeeding what was previously socially responsible investing. Conceptually, its proponents have two arguments in favor. First, it allows more factors than narrowly defined "shareholder value" to be taken into account, and this can release companies from short-termism (and also, arguably, save the planet). Second, there is the argument that it makes more money in the long term. Pollutant, short-termist smokestack companies that don't keep up with the times will underperform in the long run, and ESG allows you to spot them. In practice, as ESG has grown bigger, it has become an answer to two different and profoundly important issues. It's an attempt to counter what are seen as the negative effects of "shareholder value" capitalism. And it answers a serious problem for the investment industry. ESG got big as active managers looked for a reason to hold on to people's business in the face of competition from low-cost indexers. To fight back, passive providers such as BlackRock Inc. started systematizing ESG into indexes and became more active stewards of the companies they held. This tried to deal with the issue that their size had now made them extremely powerful, in a way that was bound eventually to attract political attention. ESG, as it is now, is very much designed to keep the money management industry going. Objections In practice, several problems have emerged. The ratings different index providers have developed can come to wildly different judgments on the same company, particularly in the diaphanous concept of "governance." And then there is "greenwashing;" investors and companies alike are finding ways to dress themselves in ESG clothing without making profound changes. Politicization of investing is already alarming the US investment industry, and has spurred many suggestions for reform.

But the key principled objection concerns shareholder value and the fiduciary responsibility of those who manage others' money. Following Milton Friedman, they should not take ESG factors into account, but base decisions on their judgment of a company's likely returns. That led to the first entry of ESG into the political arena.

The US Department of Labor has responsibility for regulating public pensions. Eugene Scalia (son of the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia), as labor secretary under former President Donald Trump, proposed a rule that would make clear that their managers could only take directly relevant investment factors into account. The version of that rule passed under President Joe Biden specifically permits ESG to be taken into account (but doesn't require this). This week, both houses of Congress voted to strike it down, invalidating ESG once again. Biden has said he will veto this. This politicization continues despite strenuous efforts by technocrats under both Trump and Biden to take the heat out of the topic. The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance said: Neither final rule singled out ESG investing for favored or disfavored treatment. The final Trump Rule did not use the term "ESG." The regulatory text of the final Biden Rule refers once to ESG investing, but only to state that ESG factors "may" be "relevant to a risk and return analysis," depending "on the individual facts and circumstances." This statement is true for all investment factors, ESG or otherwise.

But the ESGenie is out of the bottle. Disclosure Republicans in Congress have expanded this issue to include disclosure. Not only should investors not take non-financial factors into account, they argue, but regulators should not require publication of them. In what seems to me to be a stretch, Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina and others are taking on the Securities and Exchange Commission's plan that would require companies to make environmental disclosures, last week publishing a letter warning that if finalized "in any form," the rules would "unnecessarily harm consumers, workers, and the US economy." They argued the SEC was being "partisan" and "activist." Against this, the SEC isn't requiring companies to do anything, just to publish information which many investors want to know. It should also help deal with the worst confusions of ESG ratings and greenwashing, and allow capitalism to do the job of working out where capital should go when dealing with the climate crisis. Opponents are arguing that for the government even to mandate transparency on these issues is unacceptable. There's a fascinating debate to be had. Principled free-marketeers have very good reason to dislike the government in any way aiding ESG. But the latest objections are the exact opposite of Milton Friedman-style libertarianism. Enter Marjorie Taylor Greene. Universal Ownership Another pillar of the ESG investing approach is that fiduciaries must account for the broader interests of their clients; there's little point retiring rich into an atmosphere which has become unbreathable, for example. The problem for ESG advocates that the MTG school of thought represents is that it accepts their point, and turns it against them. Greene and colleagues argue that states whose economies depend on fossil fuels should go out of their way to avoid ESG funds. Pure capitalist considerations might lead fund managers to avoid coal mining groups; but those with the best interests of Kentucky or Louisiana at heart should punish such them. Or, put differently, "two can play at that game." The full culture war demonization treatment calls for carbon-dependent states to battle against ESG investing by eschewing any business that has anything to do it. Crucially, this now holds good even if it costs taxpayers money. In Florida, Matthew Winkler points out that the refusal to use banks that have underwritten ESG bonds is incurring great extra costs. Liam Denning notes that in Kentucky, which is blacklisting several big financial groups for "energy company boycotts," fossil fuel companies account for only 0.6% of the state's employment. More Politics There is now even a presidential candidate running on an almost exclusively anti-ESG platform. Much the same criticisms can be made of the anti-ESG lobby as are already made about ESG itself. Definitions are too sloppy. It's far too easy to paint everything with the same brush. But where things really get dangerous is in the political arena. If the great majority of a college's student body doesn't think its endowment should invest in fossil fuels, surely its fund managers should disinvest — even if it costs the college money. Ditto for a Catholic foundation that cannot abide investing in the makers of morning-after pills. That seems reasonable. But having accepted this principle, we slide into a position where politicians can use public funds to further their explicit political aims. A further issue is that the investment world has endowed various private sector organizations with powers that might naturally belong to elected governments. Most importantly, it was the for-profit indexing group MSCI Inc., and not any national or multinational government body, that decided it was safe for funds to invest in China. This was thanks to the prevalence of indexing. MSCI acquitted its responsibilities seriously, but surely it was crazy for such a decision to be left to them. That leads to another problem. ESG Goes Global As I've written before, trade protectionism is less an issue than it used to be. Nowadays, the apparatus of ESG and indexing make it far easier to protect your nation's economy, or to give it an unfair advantage, by putting limits on flows of capital. Sanctions with specific political aims against foreign companies are not new, and they've been known to work. Disinvestment helped force South Africa to abandon Apartheid, and, on a smaller scale, the threat by US public pension funds to disinvest in Switzerland forced Swiss banks to make a settlement with Holocaust survivors whose accounts had been allowed to go dormant. But if this is OK — and few would argue otherwise — then it becomes reasonable for democratic politicians who oversee investment funds to take national interests into account, and if necessary overrule capitalist outcomes. Specifically when it comes to China, there have already been bipartisan efforts to force government-controlled funds to exit from emerging-markets index funds, because they include Chinese companies. This is easily done; you can simply switch into an emerging-markets-excluding-China fund. Investors find it hard enough to judge whether it's safe to invest in China. It's very reasonable to question whether they will have enough protections under President Xi Jinping. But they also need to consider whether buying Chinese shares or bonds will get them into trouble with the politicians at home. Also, you don't need formal political decisions to have an effect. If trustees think investing a particular way will make life easier and save them from being tweeted about by Marjorie Taylor Green, they'll do it without being forced. And the US reaction to ESG is provoking yet another response: London-based investment managers are lugubriously reporting that European clients now tend to want to invest in "whatever Texas isn't investing in." There are arguments for free markets to make decisions like this, and arguments for democracies to do the job. What is emerging now, though, is nothing like a market discipline that Milton Friedman would recognize, and it bears little relation to democracy, either. Democracy's Deficit That brings us back to the US culture war. The chances of rational discussions of ESG are fast disappearing, as politicians can't be relied on to give an accurate assessment to voters. What started as a well-intentioned attempt to fix problems that were emerging with the capitalist model has now morphed into something much more dangerous. And it's going to be sorted out by people like Marjorie Taylor Greene. It was a much-awaited day that disappointed. And it cost Tesla Inc. a lot of money — roughly $50 billion at one point. By Thursday's close, Elon Musk's company had tumbled almost 6%, its biggest plunge in a month, reducing its market cap by $36 billion: The electric-vehicle makers' investor day on Wednesday failed to live up to the hype after Musk & Co. offered scant details about the next-generation models that many were expecting would underpin the next phase of Tesla's growth. The stock had rallied for two months, evidence of investor optimism, adding more than $300 billion of market value in that period. Investors were unsatisfied following the roughly four-hour presentation that gave little to no clarity. Here's what Franz von Holzhausen, Tesla's design chief, said at the company's headquarters in Austin, Texas: I'd love to really show you what I mean and unveil the next-gen car, but you're going to have to trust me on that until a later date... We'll always be delivering exciting, compelling and desirable vehicles, as we always have.

"You're going to have to trust me" doesn't quite cut it when you're managing a company that's been worth more than a trillion dollars, and for whose earnings investors will pay a multiple of more than 50. The average for other carmakers is about 5. To be sure, Musk did confirm its next "giga-factory" would be built in Monterrey, Mexico, in what he said was probably the most significant announcement of the day. (The news sent the Mexican peso near a five-year high.) He also announced the ground-breaking of a lithium refining plant in Corpus Christi, Texas. But none of this was transformational and shareholders disliked it:  While the centerpiece of investor expectations was left unanswered, UBS Group AG strategists led by Patrick Hummel highlighted the key aspects Tesla's management did elaborate on to become the world's leading carmaker, including a 20-million-unit target by 2030. Ken Mahoney, chief executive officer at Mahoney Asset Management, said investors may need to look past their (failed) expectations: Maybe they were hoping to hear some more raw numbers like boosting the 50% sales growth rate... We believe where investors really weren't able to read between the lines is the opportunity for service revenues. They will be able to upsell for full self-driving for example, which could cost about $15,000 for the software as they stated. They said 400,000 customers purchased full self-driving and if this is the case, you do the math, this could add billions to their revenues.

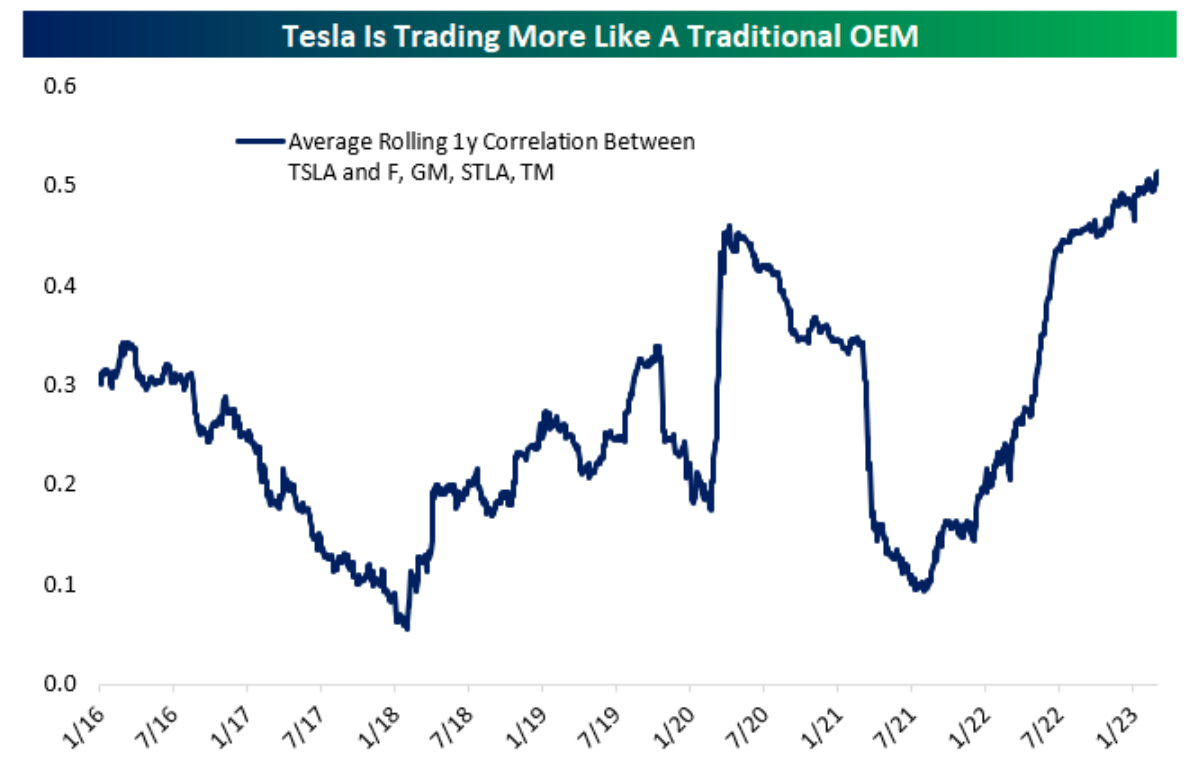

Others weren't as optimistic. Wells Fargo & Co strategists said Tesla's "timeline and cost details were limited," and JPMorgan Chase & Co. complained the event was "short on specifics or measurable metrics to track its progress." Bank of America Corp. kept its "neutral" rating and didn't expect the investor day to have a "meaningful near-term impact on the stock.'' In the eyes of ARK Innovation's Cathie Wood, Tesla remains the global EV leader, "leading the charge." But what does the market think? The chart below shows the stock, compared to the MSCI Europe Automobiles and USA Automobiles indexes. It's not hard to see Europe's automakers (blue line) are leading by far, and have made up all the ground they lost at the outset of the war in Ukraine. Tesla has lagged: The rolling one-year correlation of daily percentage changes for Tesla compared to other major original equipment-manufacturer stocks like Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co., Stellantis NV and Toyota Motor Corp., has risen to the highest level since at least 2016, George Pearkes of Bespoke Investment Group said. "In other words, the market is treating TSLA more and more like just another automaker," he added.  Bespoke Investment Group Tesla may yet make it to the moon. Musk has defied naysayers often enough. But he should heed this investor day as definitive evidence that the markets are no longer prepared to take his ambitions on trust. — Isabelle Lee It turns out that Merrick Garland, America's attorney general, is a huge Taylor Swift fan. So reveals the Wall Street Journal today. Look through his public utterances over the last decade or so and they are littered with references to Swift lyrics. His favorite song is Shake It Off — which just might be a reference to his awful experience of being nominated to the Supreme Court but never being granted a vote. After the hostile questioning he received from senators on Thursday, he showed great restraint not to say: "I knew you were trouble when you walked in." He owes his Swift fandom to his daughters, who would insist on listening to her early albums when he was driving them to school. I can confirm that daughters are fantastic for introducing me to new music — and even listened to Taylor Swift so much at one point that I began to suffer Stockholm Syndrome and chose to listen to her when I had a hundred albums to choose from on a plane. So on the subject of great daughterly recommendations, I'd like to suggest Safety Last! by Fowlmouth, of whom my daughter has just appointed herself the social media manager. I have to say it's very nice — rather reminiscent of the music Swift made in the pandemic. For some more recommendations from my daughters, try Lorde, Aurora (both of whom I've seen live in my role as a paternal chaperone), or Kacey Musgraves or Hozier. Parenthood, it's fun sometimes. Have a great weekend everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment