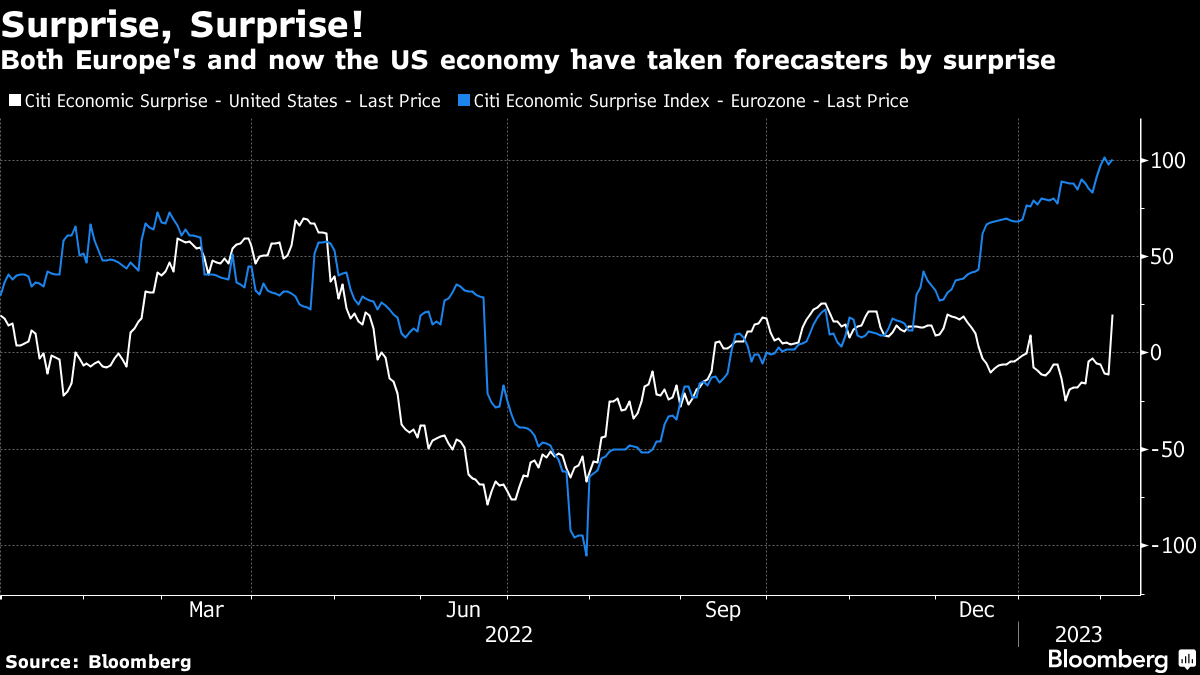

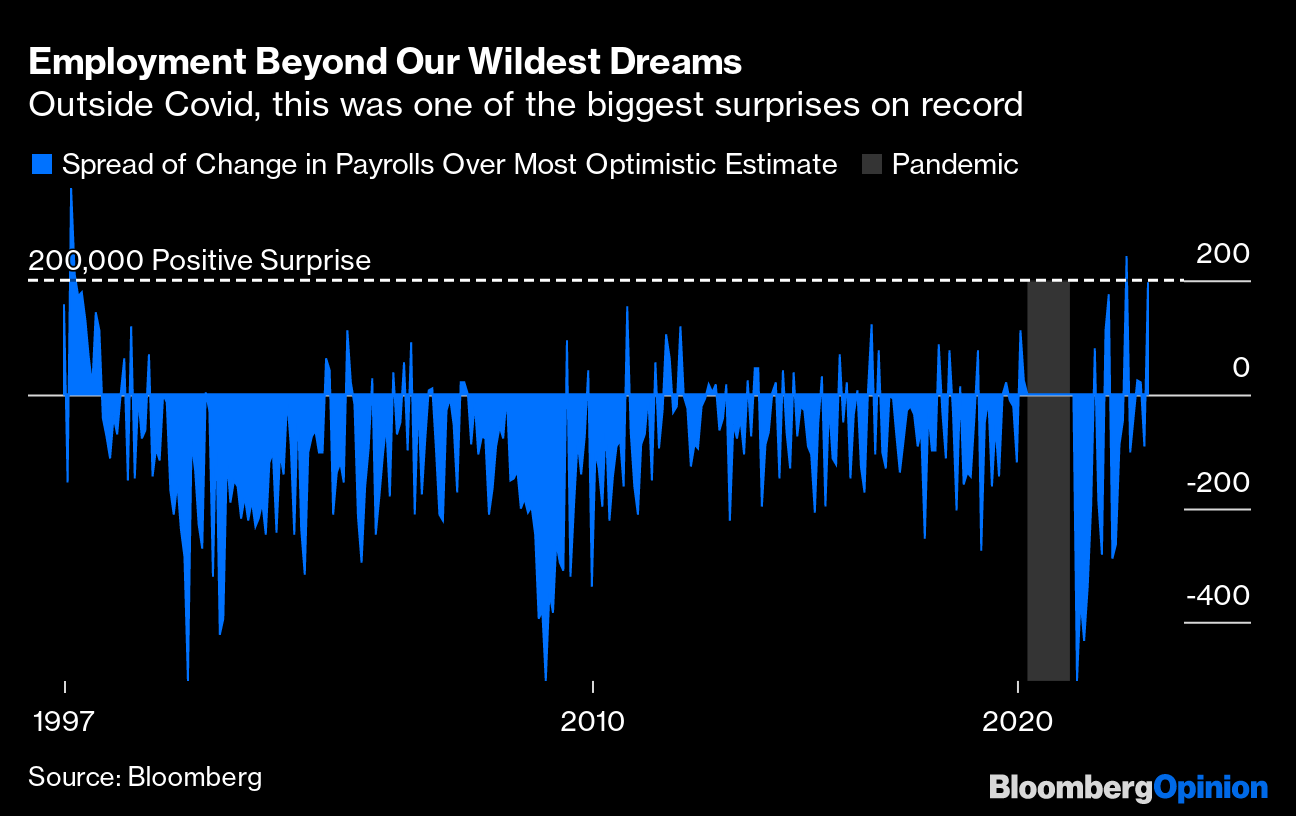

| John Maynard Keynes was one of the most influential and also divisive economists who ever lived, but almost everyone cites one of his quotations with approval. "When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do sir?" As Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal has revealed, it's not at all clear that the great man ever said this, but we can all agree with the sentiment. However clear our ideas, we need to be ready to admit that they were wrong if factual evidence shows up to disprove them. That brings us to the events of last Friday. After two days of great excitement as central banks made pronouncements and big tech companies revealed their results, the narrative for the post-Covid economy was becoming clearer. Inflation was coming down, the US was slowing down faster than Europe, and rates would soon be nudging down as the Federal Reserve aimed to ease the economy into a reasonably "soft" landing. Then, on Friday morning, the facts changed. With that, a lot of us have to work out exactly how to change our opinions. Citi's economic surprise indexes, showing the degree to which macro data is coming in ahead or behind expectation, illustrates this nicely. After a long post-pandemic period when everyone's fate was seen to be tied together, Europe has been exceeding forecasts for a couple of months, while the US data offered negative surprises. That helped weaken the dollar, among other things. But after Friday, the US is surprising positively:  The biggest shock came from the US non-farm payrolls report for January. You can gauge it most simply by watching colleague Mike McKee's face and body language when reporting the numbers on Bloomberg Surveillance. Everything seemed to point to a decline in job creation. Instead, payrolls added more than 500,000 new workers. That's very, very unusual. January's number was sharply stronger than had been seen at any point in the decade between the Global Financial Crisis and the onset of the pandemic. I've excluded the extreme Covid months from the chart for legibility: Looked at another way, Bloomberg publishes the range of estimates in its survey of economists each month. Generally, the final number doesn't exceed the most optimistic estimate very often, and if so by not very much. Leaving out the most difficult pandemic months, this was only the second time the rise in payrolls had topped the highest estimates by more than 200,000 in 25 years:  The labor market matters. The Federal Reserve (and other central banks) evidently puts the pressure from higher demands from wages at the center of its battle against inflation. If employment is weakening, that should be a sign that its medicine is working, bringing down price pressures, and readying the way to start cutting rates. This is the classic "Phillips Curve" relationship; rather than litigate whether this tradeoff captures reality, let's just emphasize that everyone thinks that central bankers think it matters. So far this year, we've had meetings from several central banks and an inflation report; but all that's really pushed the needle in the fed funds futures market has been the non-farm payroll numbers. This chart shows Bloomberg's estimate of the implied fed funds rate for the January 2024 meeting has moved during this year so far. It tumbled after the December payroll report, and rallied after the January one. Nothing else during an eventful few weeks came close:  At one point, the estimate for rates a year hence had been slashed by almost 50 basis points. Now, it's back within 10 basis points of its level for the first payroll report of 2023. This suggests what is undeniable, that the change in facts changes a sensible opinion on where rates are heading. But just how will the Fed react? Lisa Erickson, head of public markets at US Bank Wealth Management, said: The tough part of it comes in terms of the Fed reaction function. Certainly in Wednesday's press conference, they indicated some acknowledgement that there's progress in terms of disinflation, but this type of strong report could put somewhat of a kink in its plan... We are concerned that it definitely holds the Fed to a higher-for-longer path. There are of course other data points that are going to come before the next meeting, but it certainly puts a placeholder that the labor market continues to run some risk of being extremely tight.

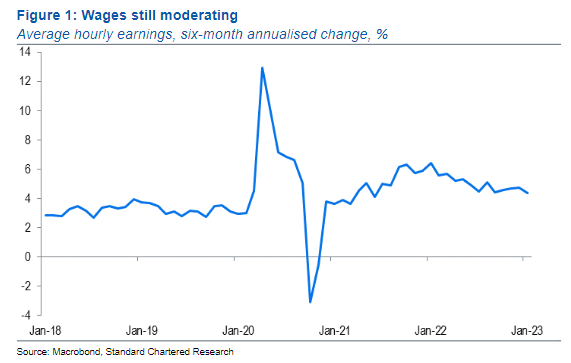

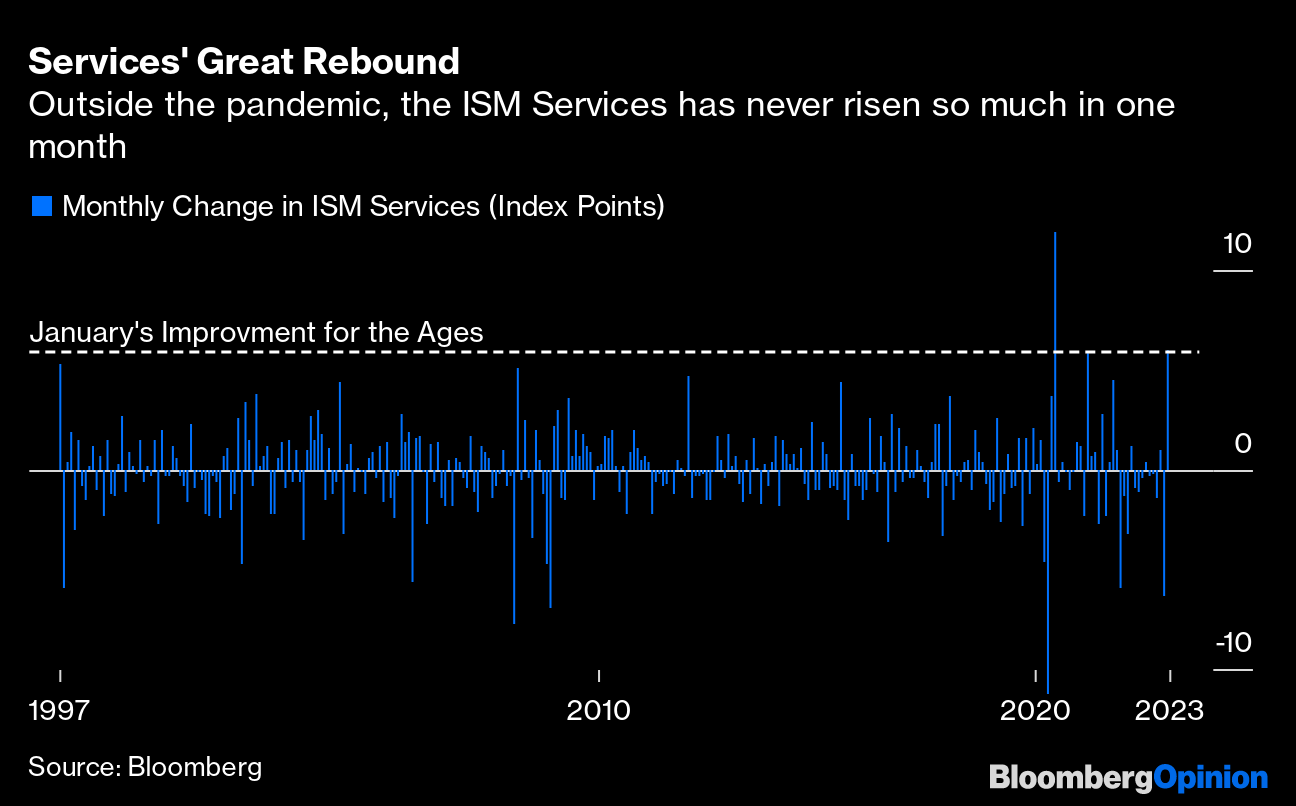

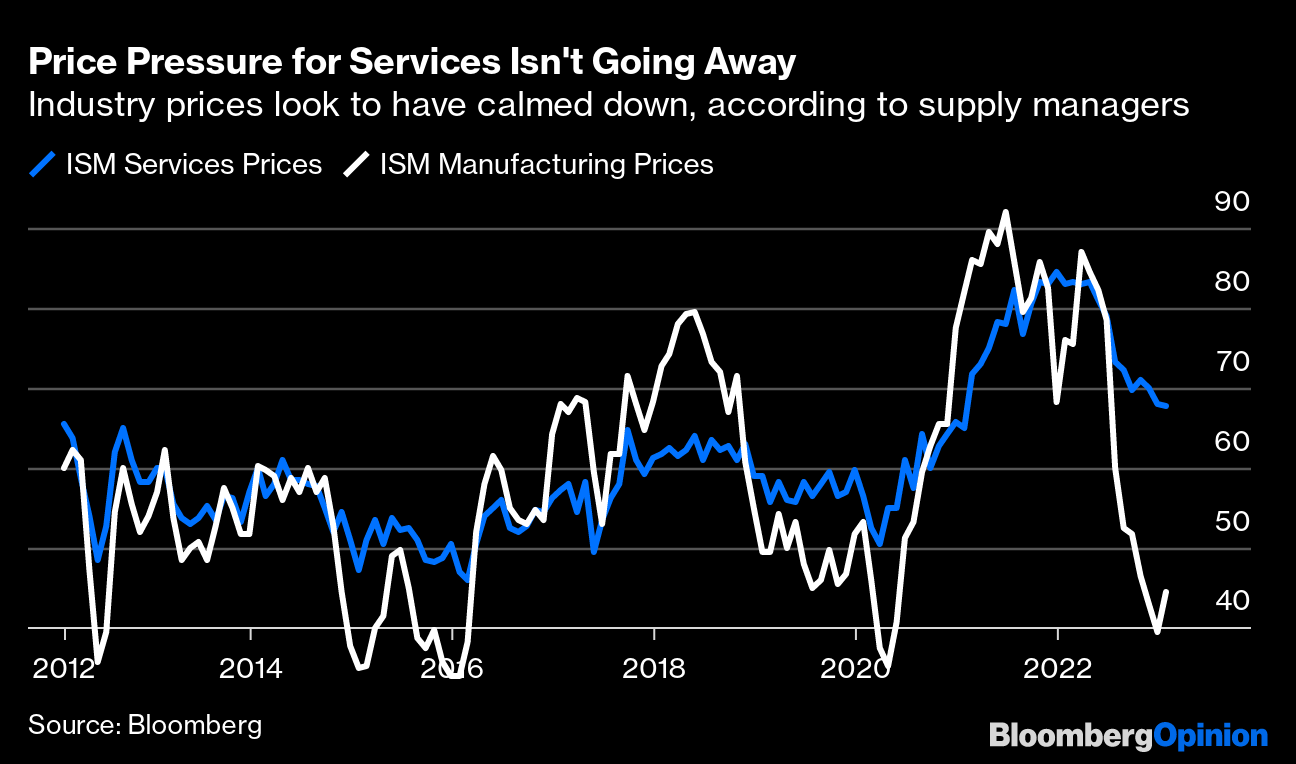

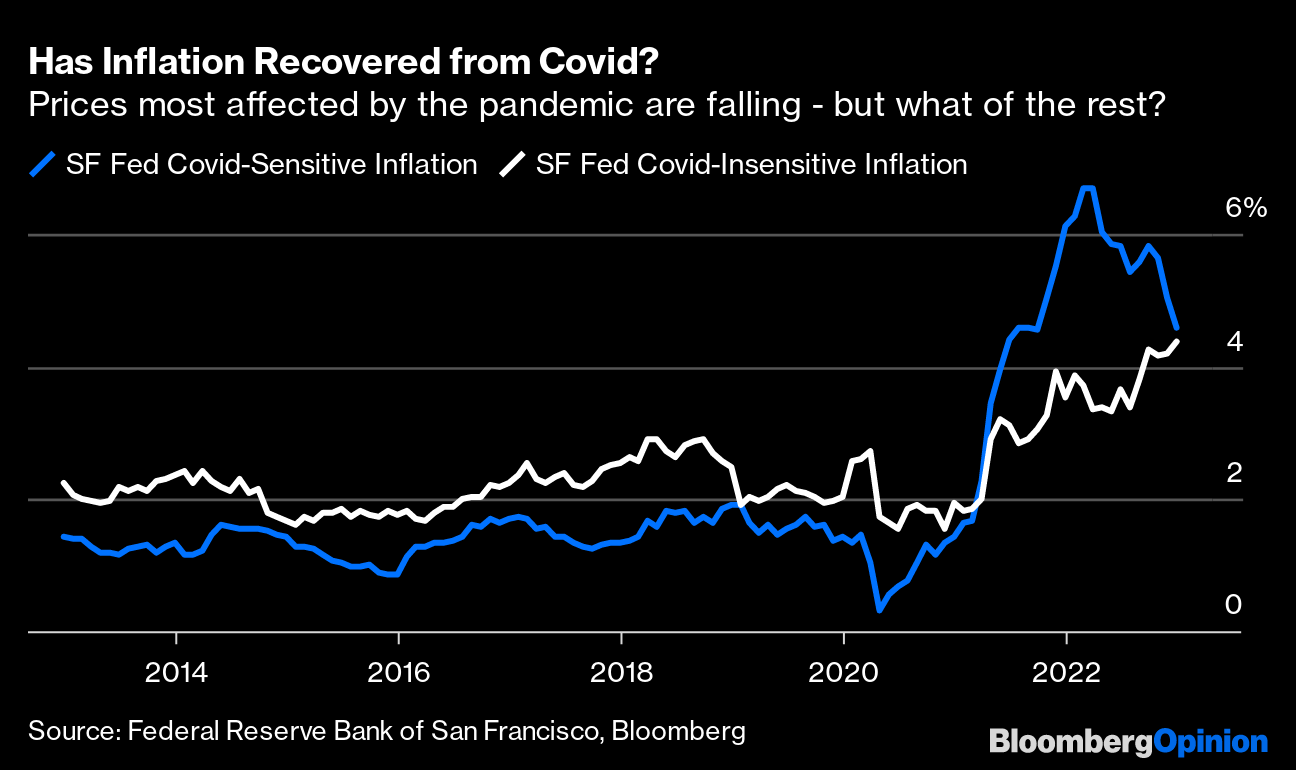

If there was one part of the report that didn't suggest overheating, it concerned wages. Average hourly earnings, when looked at on a six-monthly annualized basis, continued to decline a little, as Steven Englander of Standard Chartered PLC illustrates in this chart. So the single most direct way in which a tight labor market can tip into more inflation didn't move significantly. It does, however, remain too high for the Fed's comfort, and certainly high enough to deter any cut in the fed funds rate:  Also, employment numbers are essentially backward-looking. They're a classic lagging indicator. So maybe January's surprising surge didn't matter so much. For setting a course for the future, it's better to rely on forward-looking measures such as the ISM surveys of supply managers. The one for manufacturers, published earlier last week, was miserable, and suggested an imminent recession was close to inevitable. The one for managers in the services sector, which came out 90 minutes after the non-farm payrolls on Friday, said something very different. This survey has run since 1997, and it has only ever once increased by more from month to month (and that was during the pandemic):  Woomph. Barclays economists suggested that the new services number "was in line with prints between 55 and 60 throughout 2022, suggesting that the entirely unexpected abrupt drop to 49.2 in December was a head fake, likely reflecting unusually cold weather." The underlying trend of the services sector seems undeniably strong. If there was a plausible number to dismiss as an outlier, it was December's, not January's. Meanwhile, the way that services and manufacturing have parted company is quite remarkable. The "new orders" ISM measure (based on a factual question on whether new orders are rising or falling, rather than an opinion about the future) is a great leading indicator. And after a dramatic snapback, it would appear that services are going to enjoy a boom, just as manufacturers go into a slump: The divide between the two is the widest since the surveys started in 1997. Meanwhile, price pressures (crucial if we want to know that inflation is beaten) remain very elevated in the services sector. A slight bounce for manufacturing prices this month doesn't alter the fact that most managers are reporting price declines:  If there's an overarching explanation, it's the pandemic. A shock that great cannot be expected to pass through the system in only three years; the pig is still working its way through the python. Thus goods manufacturers have suffered the end of the boom the pandemic created for them, while pent-up demand for services continues to express itself. One way to look at this is the San Francisco Fed's measures of the prices most and least affected by the pandemic. At first, quite obviously, higher inflation was a direct effect of Covid-19; now, the goods and services unaffected by the pandemic are rising almost as fast. The key is whether the latter is really going to come under control quickly. Core inflation won't get back to target if it doesn't:  Does all of this make Jerome Powell look silly or smart? Critically, he failed last week to push back forcefully against the easing of financial conditions that has been driven by the rally of the last month. Was that because he could be confident that data would do the job of moving the market for him? Or was it exceptionally dumb because the market is showing signs of overheating? It's important not to be too binary about this. Steven Blitz of TS Lombard has been vocal in predicting that the Fed will soon cut rates, probably before it has completed the job of bottling up inflation, because a mild recession is approaching — but he made clear that the unemployment data, on its face, implied that rates short and long would have to rise because money remains too cheap.

For Blitz, the greatest danger remains that the Fed cuts too much as the economy slows later this year and inflation doesn't go away. Others take a diametrically opposed view. Alexandra Wilson-Elizondo of Goldman Sachs Asset Management agreed that the latest NFP make "insurance cuts" less likely because "there are no material signs of stress to force a rate cut." Her fear, however, is that the Fed gets more room to allow for stagnation and that risk remains skewed to an over-tightening that would cause a recession. It's not unusual for people to differ over the economy. Such a difference of opinion over what we're even worried about, however, is unusual. As Sandi Bragar, chief client officer at Aspiriant in San Francisco, says, it's "almost like we're in a pinball machine; investors are just getting hit on different angles, running into different pieces of news and it's hard to pull it all together." If you're confused, don't be ashamed and be aware that you're not alone. Uncertainty like this argues for diversification and caution. If you really want to pile into the rally in speculative assets, you could, but it might be better to acknowledge that your opinions are prone to be changed by emerging facts. Meanwhile, Friday's action in the Nasdaq-100 index, and in the ARK Innovation ETF, which manager Cathie Wood modestly describes as "the new Nasdaq," was interesting. The two are moving absolutely in line — even though ARK in theory should be more volatile. And despite the ostensible fact that higher rates should do particular damage to the case for speculative tech stocks, neither was particularly dented by the employment news. That's a reason for concern: How else should the latest facts affect our opinion? On any sensible understanding of the word "recession," the US is not about to fall into one in the next few months. The lowest unemployment rate since Lyndon Johnson was president is simply inconsistent with this. Also, it's impossible to deny that the case for a "pivot" to lower rates just got weaker. The Fed would cut rates if they appeared to be doing more harm than good. At present, with record high employment, they're doing very little harm, and therefore there's no reason to cut them, particularly while inflation, and wage rises, remain well above 2%. And for all of our sakes, it's important to acknowledge that the chance that we might all emerge from this in better shape than we entered, with high employment and a somewhat better deal for the lowest paid, remains open. Beyond that, whether Keynes said it or not, we should accept that a lot of the facts are surprising, and we might have to change our opinions. Which means that taking an aggressive position in anything is a bad idea. —Reporting by Isabelle Lee  Is Masayoshi Amamiya the one? Bloomberg There's one other piece of new news to digest. Nikkei Asia reports that the Bank of Japan's deputy governor, Masayoshi Amamiya, has been approached by the government to take over as governor in April when the term of Haruhiko Kuroda is due to end. It's still very early days, but the effect on the yen in early Australian trading was immediate (and at the time of writing has only been partially reversed in the main Asian markets). The news caused a smaller downshift for the yen than the US employment number on Friday, but it was still dramatic: As you might guess, this is because Amamiya is regarded as a "dove" who is likely to fight to continue the exceptionally loose monetary policies of Kuroda. Win Thin, currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman, explains as follows: Amamiya has been instrumental in helping Kuroda formulate and implement the BOJ's massive monetary stimulus program. Former Deputy Governor [Hiroshi] Nakaso has emerged as the other frontrunner and is viewed as slightly more hawkish than Amamiya. That said, we believe the next Governor will have no choice but to begin removing accommodation this year. Of note, Kuroda's term ends April 8 and Prime Minister Kishida has said that the replacement will be named in February.

Central bank appointments matter hugely, of course, and the early months under new leadership can be a dangerous moment as markets and bankers take each other's measure. Judging by the instant reaction, markets are behaving as though Amamiya would be a straightforward "continuity Kuroda" candidate — while Nakaso would make more of a move to tighten policy and get more into line with other central banks. They might not be right about that. As Win Thin says, the circumstances are such that whoever takes office will have little freedom of movement. And markets can exaggerate differences between candidates in situations like this. Look back to late 2021 and the way the market swooned at the news that Lael Brainard was being interviewed as a possible successor to Jerome Powell at the Fed for how these things can work. For a great compilation of initial reactions from Japan market-watchers, read this piece by my colleagues Matthew Burgess and Winnie Hsu, while in video form Kathleen Hays gives a great three-minute explanation of the politics involved here. The first read, it is plain, is that this would mean less of a shift from Kuroda-era dovishness — so you should probably sell the yen, and brace for yet another unexpected flow of liquidity into a market that already has enough of it. It also suggests yet another counterforce to the momentum that seemed to be taking the US dollar inexorably lower. The Amamiya leak combines with the Friday US data download to challenge the weak-dollar thesis.  | One tip is that the affair of the Chinese surveillance balloon, now turning into a major diplomatic incident between the world's two most powerful nations, could do serious damage to your mental health. Don't, whatever you do, try looking up what people are saying about it on social media. I'm not able to give any guidance on how this incident will affect the global balance of power — but I can at least point out that it's given all of us a great excuse to listen to a stunningly appropriate song — 99 Luftballons by Nena. Released 40 years ago almost to the day, it's a Cold War fable about how a bunch of balloons trigger a false alarm and bring out fighter pilots to shoot them down. The song ends with the world in ruins after a devastating war. It's a shame it's still relevant, but boy, is it a great song and it unfailingly lifts the spirits. Have a great week everyone.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? {OPIN <GO>}. Web readers click here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment